Catherine Darley, ND

What exactly is disordered insomnia? The patient is unable to fall asleep within 30 minutes at bedtime, or experiences significant time awake in the middle of the night. In my practice, which provides naturopathic care exclusively for sleep disorders, it is typical for patients to present with a 20-year history of insomnia. About 10%-15% of American adults have chronic insomnia symptoms (National Sleep Foundation, 2005).

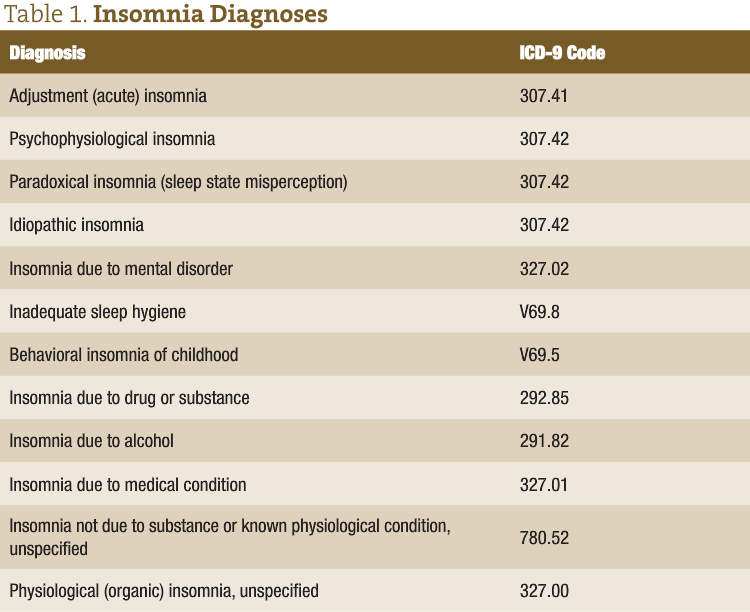

There are several types of insomnia representing different etiologies (see Table 1). A complaint of insomnia may also accompany another primary sleep disorder, such as sleep apnea or periodic limb movements of sleep. Delayed sleep phase syndrome deserves special mention, as it may be confused with insomnia but will not respond to insomnia treatment. Insomnia secondary to another disorder may resolve when the primary disorder is effectively managed. However, it may not resolve, leading to the development of psychophysiological insomnia, which we will focus on here. Psychophysiological insomnia is one of the most common types, along with adjustment insomnia and insomnia due to mental disorder (Summers et al., 2006).

Medical Model of Insomnia

The current model for understanding insomnia that is embraced by sleep specialists is one put forward by Spielman in 1986. There are three components to insomnia: predisposing factors, precipitating factors and perpetuating factors.

Predisposing factors are intrinsic characteristics that may remain stable over the individual’s lifespan. These are characteristics such as how sensitive to sound and other stimuli the person is, how easily awoken, etc. The precipitating factor is the initial event that caused adjustment (acute) insomnia. This can be a major life event – such as the birth of a child, a move, a divorce – or one of the disorders mentioned earlier. It can also be something that is considered a more minor occurrence, such as sleeping in a hotel for a few nights, having a party, etc. Precipitating events for insomnia can be from either distress or eustress. These precipitating events temporarily raise the level of sleep disturbance above the threshold for insomnia. Over time, the individual adjusts and accommodates to the precipitating event, and his or her acute insomnia resolves. That is, it resolves unless he or she has developed perpetuating factors.

Perpetuating factors are those thoughts and behaviors that maintain the insomnia, making it chronic psychophysiological insomnia. Chronic insomnia is defined as lasting more than one month. When the perpetuating factors are resolved, the person is no longer above the threshold for insomnia.

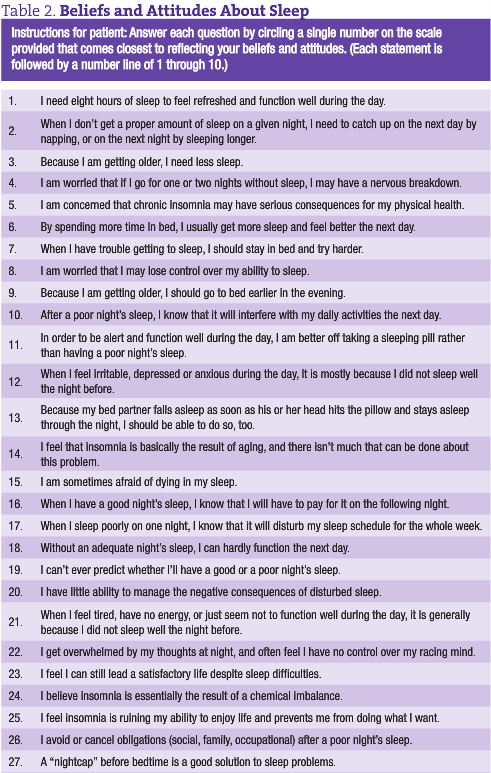

Thoughts that perpetuate insomnia include those shown in the Beliefs and Attitudes Scale (see Table 2; Morin, 1993). These are dysfunctional thoughts in that they are not sleep promoting. In fact, these thoughts increase anxiety about sleeping. Behaviors that perpetuate insomnia include spending more time in bed than is spent sleeping. For example, the patient may think, “I need 8 hours of sleep, and it takes me 2 hours to fall asleep, so therefore I should spend 10 hours in bed each night.” This conditions the patient to associate his or her bed with wakefulness. It is not uncommon for patients who have this association to report that they sleep better in a hotel, on the couch or at the in-laws’ house than they do in their own bed. When spending more time awake in bed than asleep, the sleep also can get distributed across the night so that they experience multiple awakenings and the accompanying frustration.

Thoughts that perpetuate insomnia include those shown in the Beliefs and Attitudes Scale (see Table 2; Morin, 1993). These are dysfunctional thoughts in that they are not sleep promoting. In fact, these thoughts increase anxiety about sleeping. Behaviors that perpetuate insomnia include spending more time in bed than is spent sleeping. For example, the patient may think, “I need 8 hours of sleep, and it takes me 2 hours to fall asleep, so therefore I should spend 10 hours in bed each night.” This conditions the patient to associate his or her bed with wakefulness. It is not uncommon for patients who have this association to report that they sleep better in a hotel, on the couch or at the in-laws’ house than they do in their own bed. When spending more time awake in bed than asleep, the sleep also can get distributed across the night so that they experience multiple awakenings and the accompanying frustration.

Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment for Insomnia

Perpetuating factors are the focus of Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment for Insomnia (CBT-I). CBT-I is a well-established treatment program used by medical sleep specialists to treat chronic insomnia. There are four arms of treatment: relaxation training, sleep restriction, stimulus control and cognitive therapy. CBT-I is typically conducted either individually or in a group setting each week for about eight weeks.

Cognitive therapy is done by first identifying the dysfunctional thoughts, then providing education to correct them. Relaxation techniques such as progressive muscle relaxation or slow, deep breathing can be taught. Then the patients use these when they climb into bed.

Stimulus control is used to reverse the negative association that may have developed of the bed being someplace to be awake, and all the emotions that go along with that. The patient is instructed to get out of bed in the middle of the night if not asleep, then to do something relaxing until sleepy enough to return to bed and fall asleep. In my experience, patients are very reluctant to get out of their comfortable bed in the night, but benefit from this if they can do it. Sleep restriction is to further reduce the amount of time awake in bed by limiting the patient to being in bed the amount of time they are sleeping. This increases the sleep drive by producing a slight sleep debt, further providing a positive experience of falling asleep quickly and sleeping through the night (Yang et al., 2006).

Behavioral Therapy Compared to Other Medical Treatments

Research has been done comparing the effectiveness of CBT-I with pharmacologic treatment. In one study, chronic sleep-onset insomniacs were put into four treatment groups: placebo, pharmacological therapy, CBT-I, or a combination of CBT-I and pharmacological therapy (Jacobs, 2004). The most significant improvement in sleep quality was experienced by those who used CBT-I alone, and this improvement was maintained two years after follow-up.

From my perspective, hypnotics are not as effective because they do not address the cause of insomnia. I wonder, do herbal insomnia treatments address the cause, or do they act like hypnotic medications?

Behavioral Treatment of Insomnia is Aligned with Naturopathic Principles

As NDs, we have a unique set of principles that shape our approach. A central tenant is Tolle Causam. Wherein lies the cause of chronic insomia? For those patients who respond to CBT-I, it seems that the cause lies in the dysfunctional thoughts and behaviors that have developed in response to a precipitating event. Behavioral treatment is also powerful in that it is in line with Docere. By teaching patients good sleep habits and how to work with their beliefs and attitudes, we are empowering them to care for themselves. Primum Non Nocere is another naturopathic principle. With behavioral medicine described above, patients are unlikely to experience negative side effects.

When patients present with insomnia, we can first diagnose the type of insomnia, then proceed to treat the cause. For those patients who are struggling with psychophysiological insomnia, the behavioral approach should be first line therapy, as it has been proven effective and is in accordance with our naturopathic principles.

Delayed Sleep Phase Syndrome

In delayed sleep phase syndrome, the individual’s circadian rhythms are shifted later so that sleep naturally occurs later than social norms. For example, this person will sleep well from 2 a.m. to 10 a.m. However, they may try to get to sleep earlier and wake earlier to meet their responsibilities. When they go to bed earlier and are unable to sleep, this can masquerade as insomnia. Effective treatment can shift their circadian rhythm using melatonin as a chronobiotic, light therapy in the morning to suppress melatonin and adherence to a sleep schedule.

Catherine Darley, ND is a graduate of Bastyr University and practices at The Institute of Naturopathic Sleep Medicine in Seattle. Dr. Darley is passionate about the role healthy sleep plays in overall health and quality of life, and is pioneering the field of naturopathic sleep medicine. She gained her expertise by working in the field of sleep research and medicine through naturopathic medical school, and doing multiple preceptorships and post-graduate courses with sleep specialists. In addition to providing patient care, she works to educate the public about sleep health.

Catherine Darley, ND is a graduate of Bastyr University and practices at The Institute of Naturopathic Sleep Medicine in Seattle. Dr. Darley is passionate about the role healthy sleep plays in overall health and quality of life, and is pioneering the field of naturopathic sleep medicine. She gained her expertise by working in the field of sleep research and medicine through naturopathic medical school, and doing multiple preceptorships and post-graduate courses with sleep specialists. In addition to providing patient care, she works to educate the public about sleep health.

References

- National Sleep Foundation: Sleep in America poll. National Sleep Foundation Washington, DC, 2005.

- American Academy of Sleep Medicine: The International Classification of Sleep Disorders (2nd ed), 2005, pp. 1-32.

- Summers MO et al: Recent developments in classification, Chest 130(1):276-86, 2006.

- Spielman AJ et al: Assessment of insomnia, Clin Psychol Rev 6:11-25, 1986.

- Morin CM: Insomnia: psychological assessment and management. New York, 1993, Guilford.

- Yang CM et al: Nonpharmacologic strategies in the management of insomnia, Psychiatric Clin N Am 29(4):895-919, 2006.

- Jacobs GD: Cognitive behavior therapy and pharmacotherapy for insomnia: a randomized controlled trial and direct comparison, Arch Intern Med 164(17):1888-96, 2004.