Peter Bongiorno, ND, LAc

Regular, quality sleep is of paramount importance to good mood and good health. Evaluating and solving sleep issues address a pertinent underlying cause in the pathogenesis of depression and deserve strong attention by the physician.

Depression affects almost 10% of the population1 and is often characterized by sleep disturbances, which can precede the onset or recurrence of depression.2,3 A survey of office-based physicians revealed that up to 30% of patients diagnosed with insomnia were also diagnosed with depression.4 Interrupted sleep can negatively affect circadian rhythms, causing imbalanced immunological function and unusual changes in pulsatility patterns of cortisol5 and is regarded as a symptom of an underlying depression.6 Depressed individuals exhibit prominent sleep abnormalities with dysregulation of the neuroendocrine and central nervous systems, immunological changes such as decreased natural killer cell activity, and attenuated lymphocyte and helper T cell (subtype 1) interleukin 2 activity.4 This dysregulation will exacerbate inflammation in the brain and body, contributing to depression and more sleep problems.

Sleep Apnea

There are a number of contributors to altered sleep patterns. One type of disturbed sleep known as obstructive sleep apnea is often associated with depression. In obstructive sleep apnea, affected patients have a propensity for sleepiness, traffic accidents, and hypertension.7 Upwards of 20% of patients with depression also have this comorbidity. Sleep apnea is characterized by sleep-related decreases (hypopneas) or pauses (apneas) in respiration. An obstructive apnea is defined as at least 10-second interruption of oronasal airflow, corresponding to a complete obstruction of the upper airways, despite continuous chest and abdominal movements, and is associated with a decrease in oxygen saturation, arousals from sleep, or both.8

Proper naturopathic treatment will include weight loss, support for the respiratory system to reduce inflammation, and food sensitivity and allergy work. Allopathic medical treatments include a continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) machine at night, which can often alleviate this problem. There is controversy as to whether a CPAP will help relieve the symptoms of depression. Some studies9,10 have seen clear improvement in depression scores using the CPAP, while other studies11,12 did not observe any improvement in emotional status. Compliance with the CPAP may be difficult, but in my opinion those patients who use it consistently and can move past the initial discomfort of the apparatus tend to have improvement to help remove the daytime fatigue and accompanying mood changes.

Delayed Sleep-Phase Syndrome

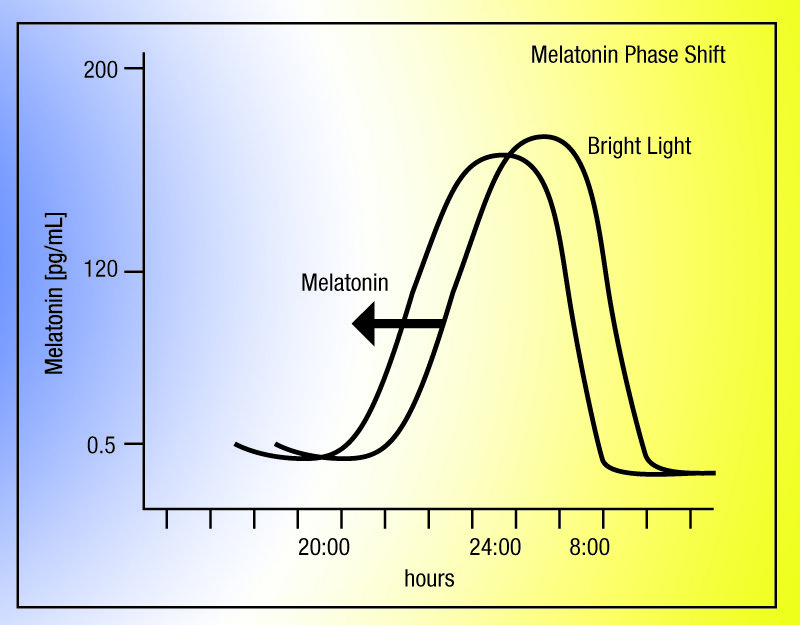

Exposure to bright light can create disruptions in sleep patterns, and it can cause delayed sleep-phase syndrome (DSPS), a common but little reported cause of severe insomnia. Delayed melatonin onset has a key role in the pathogenesis of this circadian rhythm disorder. Characteristic symptoms of the poorly defined disorder are sleep-onset insomnia and trouble waking up at conventional hours. Generally, patients with DSPS feel more alert at night than in the morning. Many suffer from hypersomnia and fatigue during the day. The prevalence of depression and personality disorders in DSPS is high.13 The Figure shows the melatonin phase shift in response to bright light.14

Figure. Melatonin Phase Shift Due to Bright Light14

Rapid eye movement (REM) sleep schedule also seems to be shifted in these patients. Specifically, the transition from wakefulness to non-REM sleep in depression is marked by the relative persistence of elevated metabolic activity in the frontoparietal regions and thalamic areas of the brain in depressed patients compared with healthy subjects. Functional positron emission tomographic scan findings of this phenomenon suggest that abnormal thalamocortical network functions may underlie sleep anomalies and complaints of nonrestorative sleep in depressed patients.15 Sleep investigations of patients with severe or moderately severe depression have shown that these patients tend to enter REM sleep unusually early compared with healthy controls. Some have an extended first REM phase, with a subsequent loss in the deeper phases of sleep. These patients often complain of early morning awakenings. Researchers looking at the sleep patterns of depressed patients found that these patients indeed have increased REM sleep in proportion to slow-wave sleep16 and that depressed patients who are deprived of REM-stage sleep showed improved mood.17

Many tricyclic antidepressants are known to suppress REM sleep, providing additional evidence for a link between REM sleep and depression. Chronic antidepressant therapy has also been shown to mediate neuronal plasticity. Noradrenergic function may also upregulate these mediators, and intravenous yohimbine hydrochloride is being studied for use during sleep to activate these pathways. Yohimbine may be a natural treatment in the future for depression accompanied by REM sleep disturbance.

Can Sleep Deprivation Help Depression?

Interestingly, it has been shown that acute sleep deprivation can actually be used as an intervention to improve depressive symptoms in unipolar depression disorder. Some studies suggest that sleep deprivation gives relief to 40% to 60% of patients with depression, whereby a full night or a half night of sleep deprivation shows a dramatic antidepressant effect. Dr Christian Gillin, at the University of California, Irvine, recommends that in an acute situation sleep deprivation can be used to treat a severely depressed patient by having him or her stay awake for half the night or more.18 According to Dr Gillin, “[T]he next morning they are lucid—elevated tremendously. They show a complete change in their motor activity, they move much more easily and readily, they can talk much better.”18 Unfortunately, even a small amount of sleep thereafter has been shown to reinitiate the depression. In some cases, as little as 1 minute of sleep puts the patient back into depression.18 As a result, this therapy had not been recommended for anything more than just an urgent care use. Some recent trials have shown that this incidence of relapse can be decreased by combining sleep deprivation with medication.19 As a long-term therapy, the unhealthful ramifications of sleep deprivation would likely supersede any short-term mood improvements. The only other treatment for depression that seems to work as quickly is ketamine hydrochloride, which may have a similar mechanism of action. Ketamine is an N-methyl-d-aspartate glutamate receptor antagonist that has shown fast-acting benefit to mood in a small trial of depressed patients, with an amazing effect on mood within 3 days.20 Unfortunately, ketamine is a fairly toxic substance.21

Steps to Help Your Patient With Depression and Poor Sleep

Given the poorly characterized yet global effects of circadian rhythm on overall hormonal regulation, it is reasonable to consider lifestyle changes in the patient with depression in order to support optimal sleep. The following are changes to recommend to the individual with depression who is looking for a better quality of sleep22:

First, inquire about sleep apnea. Have the patient video record himself sleeping or work with a sleep specialist.

Second, instruct the patient to go to bed before midnight, preferably by 10 pm. There is an old medical proverb that “1 hour before midnight is worth 2 hours after midnight.” This proverb may have merit through explanation of encouraging sleep during the time of maximum melatonin release. According to the Figure, we see that melatonin release in the adult begins at about 10 pm and increases rapidly thereafter. Getting to bed earlier than midnight takes advantage of that maximum release. Have the patient try to get to bed as early as possible. This will ensure a proper amount of REM sleep.

Third, have the patient avoid bright light around bedtime. Avoid any bright lights in the room or computer and e-mail work, etc, at least 30 minutes before bed.

Fourth, the patient should create an evening ritual. At a certain time, the lights should be dimmed, and possibly an anxiolytic tea such as chamomile or lavender can be steeped and sipped before bed. Patients suffering mood disorders often can find comfort in regular, healthful ritual where the body learns to calm and sedate for bedtime.

Fifth, instruct the patient to keep the lights dim in the bedroom. A rule of thumb is that the bedroom is too light if the patient can see her hand and foot in front of her face. Occlusive blinds or other means should be used.

Sixth, check in on your patient’s blood glucose level near bedtime. For some patients, a small amount of protein and carbohydrate (eg, a small piece of turkey and a slice of apple) may be helpful before bed to keep blood glucose levels balanced through the night. Higher-glycemic meals taken 4 hours before bed have also been shown to increase sleep onset.23

Seventh, if needed, instruct the patient to use natural remedies to help with sleep. Melatonin or l-tryptophan and 5-hydroxytryptophan (5-HTP) all have soporific effects and may be appropriate to help a patient fall asleep (melatonin) or remain asleep (l-tryptophan and 5-HTP).

Melatonin

Healthy individuals with episodic depression (the mild kind that comes and goes) and patients who have seasonal affective disorder also have lower than normal melatonin levels and have been successfully treated with melatonin in pilot investigations.24 Patients suffering from DSPS have also been found to be successfully treated with melatonin.25 I typically start patients with 1 dose of melatonin (1 mg) 20 minutes before bed and then alter the dose depending on response. Some studies have used very low melatonin doses of 0.125 mg twice in the late afternoon, each dose 4 hours apart (eg, at 4 pm and then again at 8 pm). If you find the later dosing is not working for patients, then try the low dose as given at 4 pm and 8 pm. If patients complain of excess uncomfortable dreams or of feeling groggy in the morning, then back off the dosage. I am always aware that a person with depression can be particularly sensitive to the effects of melatonin, meaning that a very low dose is generally enough to achieve the desired outcomes.26

5-HTP and Tryptophan

As a precursor to serotonin, tryptophan is well known to help sleep, and this effect is supported by study.27 I will usually recommend 5-HTP (100 mg) or tryptophan (1000 mg) before bed with a little carbohydrate (eg, a slice of apple or a piece of rice cake) before bed to help with absorption into the central nervous system. Tryptophan itself is also a well-known supplement for depression and anxiety, so it may help in more than one way. I usually use a version of tryptophan to help patients stay asleep but will also recommend sustained releases of melatonin if tryptophan is not effective.

Concluding Remarks

Finally, I highly recommend considering Passiflora incarnata (passionflower) to help with sleep. A double-blind study28 found effectiveness when used as a tea. This botanical is especially useful if your patient presents with recurring circular thoughts that keeping “spinning” in his head, without relief.

While not typical, the above remedies may also increase symptoms of depression in certain depressed individuals. As such, these patients should be monitored accordingly for any mood exacerbation.

Peter Bongiorno, ND, LAc was a predoctoral fellow in clinical neuroendocrinology at the National Institute of Mental Health (Rockville, Maryland) before attending Bastyr University (Kenmore, Washington) for his naturopathic and acupuncture degrees. He has a thriving practice in New York City and Long Island, New York. His new book, How Come They’re Happy and I’m Not?: The Complete Natural Program for Healing Depression for Good (Red Wheel/Weiser), was released at the end of 2012 and is available on Amazon. He can be contacted through www.DrPeterBongiorno.com.

Peter Bongiorno, ND, LAc was a predoctoral fellow in clinical neuroendocrinology at the National Institute of Mental Health (Rockville, Maryland) before attending Bastyr University (Kenmore, Washington) for his naturopathic and acupuncture degrees. He has a thriving practice in New York City and Long Island, New York. His new book, How Come They’re Happy and I’m Not?: The Complete Natural Program for Healing Depression for Good (Red Wheel/Weiser), was released at the end of 2012 and is available on Amazon. He can be contacted through www.DrPeterBongiorno.com.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. An estimated 1 in 10 U.S. adults report depression. http://www.cdc.gov/features/dsdepression/. Accessed December 12, 2012.

- Ford DE, Kamerow DB. Epidemiologic study of sleep disturbances and psychiatric disorders: an opportunity for prevention? JAMA. 1989;262:1479-1484.

- Buysse DJ, Frank E, Lowe KK, Cherry CR, Kupfer DJ. Electroencephalographic sleep correlates of episode and vulnerability to recurrence in depression. Biol Psychiatry. 1997;41:406-418.

- Rakecki S, Brunton A. Management of insomnia in office-based practice. Arch Fam Med. 1993;2:1129-1134.

- Irwin MR, Gillin JC, Fortner M, Costlow C. Depression: sleep and immunity. Biol Psychiatry. 1997;42(1)(supp 1):9S.

- Ringdahl EN, Pereira SL, Delzell JE Jr. Treatment of primary insomnia. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2004;17(3):212-219.

- Milleron O, Pilliere R, Foucher A, et al. Benefits of obstructive sleep apnoea treatment in coronary artery disease: a long-term follow-up study. Eur Heart J. 2004;25(9):709-711, 728-734.

- Schröder CM, O’Hara R. Depression and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2005;4:13. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1181621/. Accessed January 16, 2013.

- Derderian SS, Bridenbaugh RH, Rajagopal KR. Neuropsychologic symptoms in obstructive sleep apnea improve after treatment with nasal continuous positive airway pressure. Chest. 1988;94:1023-1027.

- Millman RP, Fogel BS, McNamara ME, Carlisle CC. Depression as a manifestation of obstructive sleep apnea: reversal with nasal continuous positive airway pressure. J Clin Psychiatry. 1989;50:348-351.

- Munoz A, Mayoralas LR, Barbe F, Pericas J, Agusti AG. Long-term effects of CPAP on daytime functioning in patients with sleep apnoea syndrome. Eur Respir J. 2000;15:676-681.

- Henke KG, Grady JJ, Kuna ST. Effect of nasal continuous positive airway pressure on neuropsychological function in sleep apnea–hypopnea syndrome: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:911-917.

- Smits MG, Perumal SR. Delayed sleep phase syndrome: a melatonin onset disorder. In: Pandi-Perumal SR, Cardinali DP, eds. Melatonin: Biological Basis of Its Function in Health and Disease. Austin, TX: Landes Bioscience; 2005.

- Bongiorno PB. Healing Depression: Integrated Naturopathic and ConventionalTreatments. Toronto, ON: CCNM Press; 2010. http://www.InnerSourceHealth.com/depression. Accessed January 15, 2013.

- Germain A, Nofzinger EA, Kupfer DJ, Buysse DJ. Neurobiology of non-REM sleep in depression: further evidence for hypofrontality and thalamic dysregulation. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1856-1863.

- Berger M, Lund R, Bronisch T, von Zerssen D. REM latency in neurotic and endogenous depression and the cholinergic REM induction test. Psychiatry Res. 1983;10:113-123.

- Vogel GW, Vogel F, McAbee RS, Thurmond AJ. Improvement of depression by REM sleep deprivation: new findings and a theory. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1980;37(3):247-253.

- Wysong P. Little sleep loss goes a long way in depressed. The Medical Post. June 4, 1996. http://www.mentalhealth.com/mag1/p5m-dp05.html. Accessed May 16, 2009.

- Wirz-Justice A, Van den Hoofdakker RH. Sleep deprivation in depression: what do we know, where do we go? Biol Psychiatry. 1999;46(4):445-453.

- Berman R. Antidepressant effects of ketamine in depressed patients. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;47(4):351-354.

- Quibell R, Prommer EE, Mihalyo M, Twycross R, Wilcock A. Ketamine. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;41(3):640-649.

- Bongiorno PB. How Come They’re Happy and I’m Not?: The Complete Natural Program for Healing Depression for Good. San Francisco, CA: Red Wheel/Weiser; November 2012.

- Afaghi A, O’Connor H, Chow CM. High-glycemic-index carbohydrate meals shorten sleep onset [published correction appears in Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86(3):809]. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85(2):426-430.

- Lewy AJ, Bauer VK, Cutler NL, Sack RL. Melatonin treatment of winter depression: a pilot study . Psychiatry Res. 1998;77(1):57-61.

- Rohr UD, Herold J. Melatonin deficiencies in women. Maturitas. 2002;41(15)(suppl 1):85-104.

- University of Maryland Medical Center. Melatonin. http://www.umm.edu/altmed/articles/melatonin-000315.htm. Accessed May 17, 2009.

- Hudson C, Hudson SP, Hecht T, MacKenzie J. Protein source tryptophan versus pharmaceutical grade tryptophan as an efficacious treatment for chronic insomnia. Nutr Neurosci. 2005;8(2):121-127.

- Ngan A, Conduit R. A double-blind, placebo-controlled investigation of the effects of Passiflora incarnata (passionflower) herbal tea on subjective sleep