June Riedlinger, RPh, PharmD, ND; Dana Ullman, MPH

Fibromyalgia is an idiopathic, chronic and complex ailment that requires the care of a professional practitioner, of which the homeopath should be considered a key player.

Substantially significant results with homeopathic treatment have been reported in the literature. Bell et al. recently conducted a study funded by the National Institutes of Health that resulted in the publishing of four articles (Bell et al., 2004a, 2004b, 2004c, 2004d). This and another well-designed study (Relton et al., 2009) found significant results in using individualized homeopathic medicines to reduce fibromyalgia symptoms. These studies and an earlier sophisticated, double-blind and crossover study (Fisher et al., 1989) showed a substantially significant degree of improvement and safety for people suffering from fibromyalgia that is not observed with conventional medical treatments. This body of evidence is worthy of attention for all clinicians who treat people with fibromyalgia. Before looking at the details of these studies, a general review of this syndrome is in order.

About Fibromyalgia

Fibromyalgia was previously called fibrositis, but this name was changed when it became evident that inflammation was not part of the condition. In 1990 the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) established criteria for the classification of fibromyalgia as a product of a multicenter study of the condition (Wolfe et al., 1990). These criteria are still used today:

- Fibromyalgia must include a history of widespread pain for at least 3 months. Widespread pain must include all of the following: pain in the left and right sides of the body, and pain above and below the waist. In addition, axial skeletal pain (cervical spine, anterior chest, thoracic spine or low back) must be present. In this definition, shoulder and buttock pain is considered as pain for each involved side. “Low back” pain is considered lower segment pain.

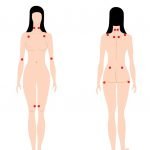

- The patient must report feeling pain in 11 of 18 tender sites on digital palpation (with approx. 4 kg of force) located bilaterally on the body.

- The presence of a second clinical disorder does not exclude the diagnosis of fibromyalgia. At present, 3-6 million Americans suffer with fibromyalgia.

Fibromyalgia affects women 10 times more often than men, and is most common in women 20-50 years old (Chakrabarty and Zoorob, 2007). This condition also has been observed in children and adolescents, and is more common in relatives of patients with fibromyalgia, suggesting the contribution of both genetic and environmental factors.

Fibromyalgia is not considered to be a “disease” by the conventional medical system, and is still referred to as a “syndrome.” Diagnosis is based on clinical findings from the history and physical exam. No specific blood tests, X-rays or other type of technology is presently accepted by conventional medicine for diagnosis of this condition.

The etiology and pathophysiology of fibromyalgia remain indeterminate, but current hypotheses to explain it include:

- Abnormal sensory processing in the central nervous system related to central sensitization with enhanced response to nociceptive input

- Activation of local nociceptors in the musculoskeletal system

- Activation of proinflammatory cytokine signaling

- Abnormalities in neuroendocrine function (Staud, 2004)

Researchers have found histological, ultrastructural and biochemical abnormalities in muscle biopsies of patients with fibromyalgia, including mitochondrial enzyme defects and increased cytokine production (Vasquez, 2008). An editorial in Arthritis & Rheumatism cited research showing alterations in pain processing in fibromyalgia patients, including altered laser-evoked potentials representing central nervous system response to cutaneous stimulation; higher cerebrospinal concentrations of substance P; diminished serum levels of insulin-like growth factor 1; and altered levels of somatostatin tone (Crofford and Clauw, 2002). The article also discussed that the ACR criterion for fibromyalgia only focus on pain symptomology and disregard other important fibromyalgia symptoms like fatigue, cognitive disturbance, sleep disturbance and psychological distress.

Thus, the syndrome of fibromyalgia includes a disparate group of physical and psychological symptoms beyond the ACR 1990 criteria, including: stiffness, fatigue, myalgias, subjective numbness, headaches (often migraine), dizziness, paresthesias, IBS-like gastrointestinal disturbances, memory and concentration problems, sleep disorders and various states of anxiety and depression (Chakrabarty and Zoorob, 2007).

Treatment: Conventional vs. Homeopathic

A recent meta-analysis of the efficacy of pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments for fibromyalgia found no clear indicator that specialized care (e.g., laser treatment, exercise, chiropractic management) provided more than the same moderate efficacy obtained in primary care settings with routine treatments (e.g., amitriptyline, tramadol) (Garcia-Campayo et al., 2008). The European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) published evidence-based guidelines for management of fibromyalgia syndrome (Carville et al., 2008). The primary recommendations for treatment include: use of a multidisciplinary approach, including non-pharmacologic (heated pool, tailored exercise programs, cognitive behavioral therapy and other patient-specific therapies) and pharmacologic (specific antidepressant, analgesic and anti-seizure drugs) interventions. These guidelines also emphasize that treatments should be specifically tailored to the patient’s report of pain intensity, function and associated features such as depression, fatigue and sleep disturbance.

Interestingly, in 2004, Goldenberg et al. published results from an extensive literature search of fibromyalgia treatment trials and found no evidence for efficacy of opioids, corticosteroids, NSAIDs, benzodiazepines and nonbenzodiazepine hypnotics, melatonin, calcitonin, thyroid hormone, guaifenesin, dehydroepiandrosterone or magnesium. Since Goldenberg’s article was published, duloxetine, milnacipran and pregabalin have attained FDA approval for treatment of fibromyalgia, and another nine drugs have achieved off-label status for treatment of fibromyalgia (Wickersham et al., 2009).

The good news for fibromyalgia patients who receive homeopathic medicines is that these remedies are not known to cause direct drug interactions with any conventional drugs the patient may be taking. The patients may also be spared from receiving some of the cornucopia of drugs that conventional medical doctors use to control symptoms. Further, because people with fibromyalgia tend to have distinct and unusual symptoms, it is easier for homeopaths to treat them successfully because, for homeopathy, all ailments are syndromes; that is, all disease is a constellation of physical and psychological symptoms, and each patient has his or her own distinctive version of the disease. The fact that people with fibromyalgia tend to have sometimes subtly or overtly differing symptoms from each other is no significant problem for homeopaths because each person is observed to have his/her own syndrome of symptoms, no matter the diagnosis.

Other advantages of homeopathy over conventional drug therapies include less cost for medications and avoidance of the usual side effects of GI complaints, headaches and CNS disturbances, as well as the potentially life-threatening reactions to conventional drug therapy. However, homeopaths have also observed empirically that a small percentage of people with fibromyalgia are so ill and their immune system so compromised that it is difficult to provide effective treatment. Also, the drug therapies patients may be taking, most of which should not be abruptly discontinued, may make it more difficult to get curative results with homeopathic medicines.

Trials and Studies

Despite the various articles and books on fibromyalgia, it is unfortunate that few make reference to any studies published in a major medical journal showing the efficacy of homeopathic medicine in the treatment of people with this syndrome. While homeopathy is not commonly mentioned in publications covering treatment of fibromyalgia, Wahner-Roedler et al. (2005) found that 10% of patients (N=289) answering a survey on their use of complementary and alternative medicine for fibromyalgia symptoms reported using homeopathy. In contrast, a survey of members of the ACR found that 75% of the sample (N=924) reported homeopathy to have no clinical use; 21% reported having enough knowledge to discuss homeopathy with a patient; and 4% considered homeopathy to be a legitimate medical practice (Berman et al., 2002).

The first controlled trial testing homeopathic treatment of patients with fibromyalgia was an impressive double-blind crossover trial in 1989 (Fisher et al., 1989). Because of the nature of a crossover trial, the researchers chose to accept into this study only those patients who fit the symptom-syndrome for needing Rhus toxicodendron. Researchers found a surprisingly high percentage of patients (42%) whose symptoms indicated this need.

These 30 patients were given a 6C homeopathic dose (the researchers specifically used a low-potency dose because they wanted to elicit short-term results). They found a substantially significant degree of improvement in the reduction of tender points (P=<0.005) and improved pain or sleep (P=0.0052) when subjects were taking the homeopathic medicine as compared to placebo.

A more recent study published in Rheumatology (Oxford, England) also found statistically significant results from homeopathic treatment. Researchers from the University of Arizona in collaboration with homeopaths conducted a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial with 62 fibromyalgia patients (Bell et al., 2004a). Patients were randomized to receive an oral daily dose of either an individually chosen homeopathic medicine in LM potency or a placebo. Patients were evaluated at baseline, 2 months and 4 months.

The study found that 50% of patients given a homeopathic remedy experienced a 25% or greater improvement in tender point pain upon examination; only 15% of those who were given a placebo experienced a similar degree of improvement (P=0.008). After 4 months, the homeopathic patients also rated the “helpfulness of the treatment” significantly greater than those who were given a placebo (P=0.004). It is therefore not surprising that the study also reported that the average number of remedies recommended by the homeopaths was substantially higher in the placebo group than in the active treatment group.

One additional feature of this trial was that the first dose was given by olfaction, and both groups were monitored with EEG. The researchers found a significant and identifiable difference in the EEG readings in patients who were given a remedy vs. those given a placebo (Bell et al., 2004b, 2004c). Each patient had three laboratory sessions: at baseline and at 3 months and 6 months after initial treatment. Researchers found that the active treatment group experienced significant increases in the EEG-relative alpha magnitude (an indicator of a relaxed, less anxious state), while patients given a placebo experienced a decrease in this measurement (P=0.003).

In addition, the study included an optional crossover design, allowing patients who had initially been prescribed one treatment (placebo or remedy) to switch to the “other” treatment (Bell et al., 2004d). Researchers found that 31% of patients who had been prescribed the medication chose to switch, while 41% of patients who had been prescribed the placebo chose to switch. It was also found that initial homeopathic remedy choices over the entire sample were highly individualized, even to the same degree across subgroups.

The combined evidence of clinical improvement along with objective physiological response from the homeopathic medicine gives the results of this trial additional significance.

The newest randomized controlled trial was conducted (N=47 patients) comparing “usual care” compared with usual care plus adjunctive care by a homeopath for patients with fibromyalgia syndrome (Relton et al., 2009). “Usual care” refers to one or more of the following: physiotherapy, aerobic exercise, analgesics, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antidepressants; “adjunctive care” consisted of five in-depth interviews that led to the prescription of individualized homeopathic medicines. The primary outcome measure was the difference in the Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ) total score at 22 weeks.

The dropout rate in the homeopath care group was less than in the usual care group (3/23 vs. 8/24), and no adverse effects were reported in this study. Outcome changes for completers, adjusted for baseline, showed that the homeopathic care group had a significantly greater mean reduction in the FIQ total score than the usual care group (-7.62 vs. 3.63). The researchers also found significantly greater reductions in the homeopath care group in both the FIQ “fatigue and tiredness upon waking” score and the McGill pain score. Although the study observed a small improvement in the FIQ pain score for the homeopath care group, the FIQ “number of days felt good” score was statistically significant for the homeopath care group compared to the usual care group (0.95 vs. 0.06).

Ultimately, homeopathic treatment of patients with fibromyalgia requires individualized care from clinicians who are adequately trained in homeopathy. The body of scientific evidence showing efficacy of individualized homeopathic treatment in the care of patients with fibromyalgia suggests significant benefits. NDs with specialized knowledge of homeopathy should consider providing such treatment to fibromyalgia patients, and others might consider referring these patients to certified homeopathic practitioners.

June Riedlinger, RPh, PharmD, ND practices in Boston and is a graduate of SCNM. Previously, she was an associate professor of pharmacy practice at Massachusetts College of Pharmacy, focused on developing educational materials and programs to facilitate the allopathic medical practitioner’s understanding of naturopathic modalities. She has always been passionate about making sure patients obtain the most benefit and least possible harm from any therapeutic intervention.

June Riedlinger, RPh, PharmD, ND practices in Boston and is a graduate of SCNM. Previously, she was an associate professor of pharmacy practice at Massachusetts College of Pharmacy, focused on developing educational materials and programs to facilitate the allopathic medical practitioner’s understanding of naturopathic modalities. She has always been passionate about making sure patients obtain the most benefit and least possible harm from any therapeutic intervention.

Dana Ullman, MPH has authored 10 books – including The Homeopathic Revolution and Everybody’s Guide to Homeopathic Medicines, numerous chapters in medical textbooks and hundreds of articles. His website (www.homeopathic.com) is a leading source of information, books, research, software, courses and medicines. Ullman has also authored an ebook, Homeopathic Family Medicine, which provides a comprehensive and up-to-date review of 200+ clinical trials on homeopathic medicines.

References

Bell IR et al: Improved clinical status in fibromyalgia patients treated with individualized homeopathic remedies versus placebo, Rheumatology (Oxford) 43:577-82, 2004a.

Bell IR et al: EEG alpha sensitization in individualized homeopathic treatment of fibromyalgia, Int J Neurosci 114(9):1195-1220, 2004b.

Bell IR et al: Electroencephalographic cordance patterns distinguish exceptional clinical responders with fibromyalgia to individualized homeopathic medicines, J Altern Complement Med 10(2):285-99, 2004c.

Bell IR et al: Individual differences in response to randomly assigned active individualized homeopathic and placebo treatment in fibromyalgia: implications of a double-blinded optional crossover design, J Altern Complement Med 10(2):269-83, 2004d.

Berman BM et al: Use and referral patterns for 22 complementary and alternative medical therapies by members of the American College of Rheumatology: results of a national survey, Arch Intern Med 162:766-70, 2002.

Carville SF et al: EULAR evidence-based recommendations for the management of fibromyalgia syndrome, Ann of the Rheum Dis 67:536-41, 2008.

Chakrabarty S, Zoorob R: Fibromyalgia, Am Fam Physician 76(2):247-54, 2007.

Clin-eguide: Drug Information. Facts & Comparisons 4.0. Indianapolis, 2009, Wolters Kluwer Health.

Crofford LJ, Clauw DJ: Fibromyalgia: where are we a decade after the American College of Rheumatology classification criteria were developed?, Arthritis Rheum 46(5):1136-38, 2002.

Wahner-Roedler DL et al: Use of complementary and alternative medical therapies by patients referred to a fibromyalgia treatment program at a tertiary care center, Mayo Clin Proc 80(1):55-60, 2005.

Fisher P et al: Effect of homoeopathic treatment on fibrositis (primary fibromyalgia), BMJ 299(6695):365-6, 1989.

Garcia-Campayo J et al: A meta-analysis of the efficacy of fibromyalgia treatment according to level of care, Arthritis Research & Therapy 10(4):R81-96, 2008.

Goldenberg DL et al: Management of fibromyalgia syndrome, JAMA 292:2388-95, 2004.

Relton C et al: Healthcare provided by a homeopath as an adjunct to usual care for Fibromyalgia (FMS): results of a pilot randomised controlled trial, Homeopathy 98(2):77-82, 2009.

Staud R: The neurobiology of chronic musculoskeletal pain (including chronic regional pain). In: Wallace DJ, Clauw DJ, eds. Fibromyalgia & Other Central Pain Syndromes. Philadelphia, 2005, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 45-62.

Staud R: Fibromyalgia pain: do we know the source?, Current Opinion in Rheumatology 16(2):157-63, 2004.

Vasquez A: Clinical focus: fibromyalgia. In Vasquez A (ed): Musculoskeletal Pain: Expanded Clinical Strategies (Functional Medicine Clinical Monographs). Gig Harbor, 2008, The Institute for Functional Medicine, pp97-107.

Wickersham RM et al (eds): Facts and Comparisons (updated monthly). St. Louis, 2009, Wolters Kluwer Health.

Wolfe F et al: The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of fibromyalgia. Report of the Multicenter Criteria Committee, Arthritis Rheum 33(2):160-72, 1990.