David Schleich, PhD

Education

Professional Formation of the Square

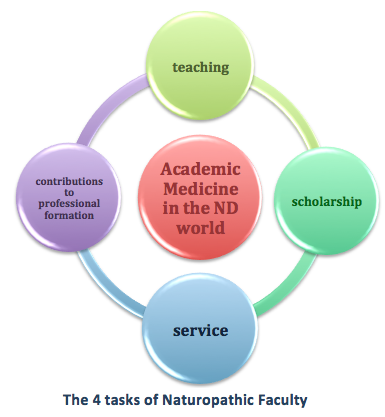

In the higher education field, which impinges as never before on naturopathic education, there is a persistent debate underway about the changing nature of work in academic medicine. Traditional research universities understand the faculty member’s job to consist of the triad of teaching, scholarship, and service. But there is more. Just as their allopathic colleagues in academic medicine centers do, naturopathic faculty also have related professional affiliations. For example, medical academics often belong to state and national associations, and some volunteer on accreditation committees, licensing boards, legislative committees and conference planning committees. As the burgeoning integrative medicine sector stakes bigger claims in mainstream healthcare, the distinctions between healthcare professionals are becoming less distinct. There are proud announcements from the biomedicine sector about the proliferation of integrative medicine programs, and a robust lineup of continuing medical education (CME) opportunities supports new learning and spreads timely ideas about how to organize the curriculum to assimilate holistic principles and products. The CME industry proffers advice about how to monetize those new modalities and protocols in the shifting landscape of the business of medicine. The fourth piece of the academic medicine job, then, is professional formation.

Our faculty has an increasingly important role in all this transformation. There are unforgiving forces banging at the gates and pressuring the pace of change, not least of which have been the recent announcements of a potentially disruptive, less inclusive, attitude on the part of the federal government toward health, which will likely result in the dismantling of some aspects of the Affordable Care Act. Another and more prominent force, well known to everyone in healthcare, is the undeniably growing chronicity of health problems faced in America.

Back at the ranch, our colleges, universities and programs face mounting urgency as we try to choreograph professional education, translational research, and patient care in our teaching clinics into achievable performance outcomes in the experience of our students. Our school leaders are pretty good at stretching scarce resources to serve student, patient, and faculty needs, but our tried-and-true ways of preparing doctors for a clinical career characterized by prevention and patient-centered care are currently being hijacked by mainstream allopathic medicine. Hundreds of so-called “integrative clinics” around North America are taking what our NDs have safeguarded for years and using them as “branding bits” for what they are touting as a new approach in academic medicine centers around the country. The reality is that these biomedicine entrepreneurs have lately discovered what NDs have been offering for over a century and assimilating the highlights into their practices with impunity even though the American Medical Association and the Canadian Medical Association have attacked NDs for the very same clinical practices and principles unrelentingly for decades. This political and social shift is a significant challenge for our naturopathic medical educators who have to protect naturopathic philosophy at the same time as they have to prepare our graduates for entry into primary care landscapes.

Healthcare Terrain Pressures

These and other discernible environmental factors are afoot as we consider the best approaches to teaching and learning. What we ask our faculty to accomplish requires increasingly precise description and assessment. What do we mean exactly when we add phrases to job descriptions such as “facilitating learning” or “efficient and invitational approaches to evaluating?” We expect our faculty to build an environment that has the student front and center, that encourages collaboration among colleagues, and that includes rapid adoption of educational and communications technology. Taking up the rear are expectations for willing contributions to the classroom research that incubates continuous improvement in student learning.

It is fascinating to examine curriculum revisions in naturopathic medical education in recent years. Prominent among these changes is the commitment to placing students and their learning needs ahead of institutional and faculty preferences. This priority has been studied diligently in higher education institutions in North America for over 2 decades. Beginning with the school reform movement in the US and Canada in the 1990s, education professionals have embraced the notion that learning is not isolated from the needs of society. In our case, this means that naturopathic learning is informed by the needs of the profession, the needs of patients, and the location of the profession in the larger social economy. Naturopathic medical education, then, is a “product,” the success of which is measured not only by the academic tools of the teacher and the degree-granting power of the institution but also by the extent of consumer use. The consumer of our product, at first, is the student, but ultimately, it is the patient. Enduring cash flow, then, to keep it all going, is contingent on verifying for potential students that our graduates are delivering good health services and that the future is friendly in terms of student debt repayment. Indirectly, the priorities of the credentialing body remain an important part of this continuum, but the more vital deliverable is the quality of, and demand for, ND services. The advent of constituent-based education, like patient-centered health care, presses our teachers and their leaders constantly, since data about employment outcomes are part of the work of the medical academic.

Our faculty also has to contend with demands attached to the rapid transformation of naturopathic profession organizations in North America. One challenge is the uneven growth of regulated jurisdictions; another is the integrative medicine sector of the allopathic profession cherry-picking parts of naturopathic care. With regard to uneven legislation, even the newest states (Minnesota, North Dakota, Colorado, Maryland and Pennsylvania) have varying practice frameworks for NDs. At the same time, there is continuous drift, discussed often in academic medicine, toward biomedicine principles and practice. Do we, or do we not, vaccinate patients—from babies to seniors—umpty-9 times in a lifetime? How much do we default to prescription drugs? Can we ramp up our research efforts fast enough to catch the wave of integrative and multi-disciplinary opportunities? Do we yield to the implicit control of third party payers to define treatment plans? Academic medicine today is about all of these questions, and more. As a faculty member put it recently, “Would that we could go back to when I was a teacher of naturopathy only, in the old days, and not the teacher-healer-lobbyist-advocate-tinker-tailor-soldier-spy I am now?”

Regulatory Pressures

This professor from Ontario, the world’s largest (for the moment) jurisdiction of credentialed naturopathic professionals, was commenting on recent regulatory changes, which have influenced how he functions as a naturopathic professional. He sees this change as a signal of shifting priorities. In his view, the new lay leaders of the profession in Ontario exhibit less interest in, and understanding of, the formation of the naturopathic profession in North America, especially regarding the philosophy of the medicine; at the same time, they are, by default, accelerating the drift toward what he calls a biomedicine temperament in regulatory and public policy matters. As a historically eclectic ND, he and others feel threatened from within. In addition, he insists, the cost of regulation has skyrocketed. Being a teacher isn’t what it used to be.

In the US, naturopathic medical faculty speak to this same drift and these same pressures. Some worry, for example, that the focus of legislative change too often pivots around pharmacopeias and controlled acts, another kind of drift away from the old modalities. Those traditional modes of naturopathic medicine are difficult to monetize, they explain, are labor-intensive, and in many cases are only thinly supported by research. There is a lament afoot that lack of interest by many state association leaders, whose members are laboring under huge student loan debt, reflect an effort to fit in, rather than a ditching of philosophy. In any case, the elders of the profession are increasingly alarmed by an arriving generation of NDs who are especially attracted to the elements in their scope that make a place in the healthcare terrain more recognizable and secure as “primary care physicians.”

These contests of professional identity exert huge pressure on the teachers back in the college and university programs. They are left to wrestle with landmark familiar questions: from whom will they take their lead in scholarship, mentoring, and service? Who will make the important curriculum decisions that define and demarcate programmatic accreditation standards? And what questions will be cycled into the next iteration of NPLEX?

Pressures from Historical Regionalism

The historical regionalism of the profession also affects our faculty. This regionalism arises because of the persistent uneven distribution of our small numbers of registrants against the gestalt of professional medicine in general. The ratio is whacky: 1,000,000 allopathic doctors versus less than 8,000 NDs across North America. Despite this, the impact of the ND cohort is substantial. The Patient Protection and Affordability Care Act (PP/ACA) in the US signaled the formal recognition of a more inclusive environment for NDs in healthcare, but the recent election has made the future of that recognition less clear. Our faculty knows that, in order for our graduates to feel confident about a forty-year career, a new consciousness based on an understanding of the need for a national consensus on practice standards, labor mobility, and scope of practice differentiation is needed. An examination of federal, state and provincial regulatory issues, and variations in professional training and credentials, is also necessary. The future of the profession depends on the coordinated efforts of strong national organizations to spearhead its growth in both the US and Canada. Our faculty struggles to source good information and guidance in this fourth part of the faculty member’s burden: professional formation.

Related to this dynamic is the regional disparity in professional growth. In Canada, the largest groups are in Ontario and British Columbia, while in the US, NDs are most highly concentrated on the West Coast. This demographic, though, is about to change. The growth in the number of NDs in the Great Lakes Basin and the Northeast will outpace that of the BC-to-Arizona backbone of the profession by the early 2030s. The new program at Maryland University of Integrative Health and the likelihood of a new program in the Southeast may also shift the historical patterns of numbers. At the same time, though, the launch of another new ND program in North Orange County, California, will temper any rapid shift in the East-West balance. Watch for more ND programs taking shape in the Northeast, the Mid-Atlantic, and the Southeast soon enough.

Pressures of Specialization

Specialization is another factor impacting our faculty. Curriculum has historically been defined around faculty specializations of interest and availability. The older notions of lineage (Dr Bastyr and Dr Boucher in the Pacific Northwest, Dr Broadwell in Kansas and California, or Dr Koegler and Dr LaPlante in Ontario) are no more. Incoming faculty members must exhibit, to be chosen for a full-time appointment, a comprehensive grasp of naturopathic modalities. Their clinical experience is not great, most often, although that is improving. Specializations in fields such as cardiology or botanical medicine are desirable but not necessarily sustainable, not only because of the cost of recruitment and retention, but also because of the shifting nature of the faculty job itself. Academic medicine is as much about teaching and research as it is about clinical skills and politics. And, churning in the aisles of classrooms are the expectations of millennials who have their eyes trained on how they will earn a living when they graduate. They want models of excellence to emulate. More and more of them want to be employees, rather than entrepreneurs, and our best entrepreneurs simply don’t have time to spend in classrooms except as occasional guests.

Competition, Accountability, and Monday Morning Under-Preparedness

Our faculty also contend with the inevitability of increasing competition in our key program areas: integrative curriculum (formerly known as Complementary and Alternative Medicine [CAM] curriculum) is surfacing in mainstream university and college programs, as private for-profit organizations are joining the party. Southern California University in Whittier, CA, has even launched a new Physician’s Assistant program initiative alongside its plans for the rollout of another ND program in our Council on Naturopathic Medical Education (CNME) network. Stand-alone program colleges will be increasingly difficult to sustain because of these incursions into our historical markets.

Our faculty is further pressed by their students, as future-yearning millennials seek accountability not only for how the employees of the institution spend their time on the student’s dime, but also for the results of that time spent accomplishing the institution’s mission. In such a terrain, licensing exam results are seen to reflect not only on the student but on everyone who was part of getting them to the gates of the profession, including teachers, support staff, and administrators. The very design of the Naturopathic Physicians Licensing Examinations (NPLEX) entry-to-practice turnstile is not immune from the vagaries of the marketplace, either. The work of the American Association of Naturopathic Physicians and the Association of Accredited Naturopathic Medical Colleges draws resources from those same students, students whose Naturopathic Medical Student Association has grown strong in recent years and often has much to say about where the profession is headed. It is noteworthy that higher and more diverse expectations among potential students about what the curriculum will do for them are influencing their decisions to enroll or not in our programs, and sometimes evolves into a later decision about whether to stay. Once they are enrolled, we see greater numbers of students who are under-prepared in language and numeracy skills, general education, and basic sciences, thus requiring the institution to monitor and remediate more pro-actively than before. In other words, our teachers have more to contend with.

Research Pressures

Another challenge is the critical need for institutional research, as distinct from naturopathic medical research. This means regular assessments of the profession, with 1, 3, 5 and 10 year (and even longer) windows. Through comprehensive, cumulative assessments, we must routinely review the natural health sciences industry environment, including all of the regulatory and other factors affecting natural health care professionals and the corporations serving them, and data about the success rates of our graduates within this environment. This is not to be confused with academic and clinical research, the content of which is informed by naturopathic medical therapies, materials, and theories. The fact that key performance indicators, predicated on best practices, are increasingly central to the mission of institutional researchers speaks to the urgency of a co-coordinated research mission for the naturopathic profession in North America. In other words, the content and learning outcomes of our ND programs, the content and outcomes of a naturopathic research agenda, and the performance of the overall institution in which these tasks are occurring need to be seen as integrated pieces of the whole. We can no longer work in isolation, separate and apart from other institutions; rather, the future lies in joint ventures and inter-institutional collaboration between naturopathic medical schools and other multi-program colleges and universities of natural medicine, Canadian and American university faculties of medicine and allied health sciences, and federal agencies such as the National Institutes of Health and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

The institutional and organizational maturing of accredited naturopathic programs, whether in stand-alone institutions or programs inside universities, will help to create a more homogeneous understanding by the public and by other healthcare professionals about what we do and why. These new relationships will make it possible for our students to transfer their educational credits to other graduate institutions for further higher education purposes, as well as to partner with these other institutions in research projects and development projects related to naturopathic medical education and to the natural health sciences.

Our faculty is under pressure, too, to keep the profession connected, in a formal and systematic way, to the core ND program. This means establishing advisory committees to provide consultation regarding scope, currency, and relevance of curriculum content, regulatory transformation, and the ability of the professional-in-the-field to compete inter-professionally.

The Ingredients of a Naturopathic Academic Career

NDs with an inkling to be teachers need to be able to demonstrate not only successful completion of academic work and appropriate clinical experience but also research skills. In the biomedical sciences curriculum, teachers arrive to our faculty ranks with completed PhDs from accredited institutions, demonstrated evidence of ongoing research activity and publications, as well as knowledge about the naturopathic profession, its philosophy and its principles. Teaching in our institutions is increasingly seen as a viable career pathway as salaries edge up and programs proliferate.

The teachers in our programs will be increasingly called on to support continuing medical education. Their contributions will be reflected in formal assignments and will complement their professional growth interests. The growing presence of multi-program universities, in which the training of NDs constitutes the lead program, has significant implications for the differentiating of our faculty’s interests, resources and networks. Inter-professional training will invariably become the norm for our teachers. The recent Academy of Integrated Health & Medicine presence in the Oregon Collaborative for Integrative Medicine network is a case in point of this kind of collaboration. Other professions will increasingly turn to NDs as trainers of choice for CAM training, as ND presenters in integrative venues will attract other health care professionals, including medical doctors, registered nurses, nurse practitioners, homeopathic practitioners, herbalists, chiropractors, acupuncturists and traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) practitioners.

The role and promise of an academic career in naturopathic medicine have never been more exciting, or more possible, than in our era; to the triad of teaching, scholarship, and service is added the essential ingredient of professional formation work. Critical, though, to moving these imperatives forward is excellent academic leadership. That challenge, it needs to be said, is another story.

David J. Schleich, PhD, is president and CEO of the National University of Natural Medicine (NUNM), former president of Truestar Health, and former CEO and president of CCNM, where he served from 1996 to 2003. Previous posts have included appointments as vice president academic of Niagara College, and administrative and teaching positions at St. Lawrence College, Swinburne University (Australia) and the University of Alberta. His academic credentials have been earned from the University of Western Ontario (BA), the University of Alberta (MA), Queen’s University (BEd), and the University of Toronto (PhD).

David J. Schleich, PhD, is president and CEO of the National University of Natural Medicine (NUNM), former president of Truestar Health, and former CEO and president of CCNM, where he served from 1996 to 2003. Previous posts have included appointments as vice president academic of Niagara College, and administrative and teaching positions at St. Lawrence College, Swinburne University (Australia) and the University of Alberta. His academic credentials have been earned from the University of Western Ontario (BA), the University of Alberta (MA), Queen’s University (BEd), and the University of Toronto (PhD).