Docere

Anup Mulakaluri, ND, AWC

Cannabis has a documented history of clinical use that spans thousands of years in the traditional medicines of Asia and Europe. As the prevalence of the opioid epidemic has made the medical community desperate for effective alternatives, cannabis has re-emerged as one of the most effective alternatives for pain management.

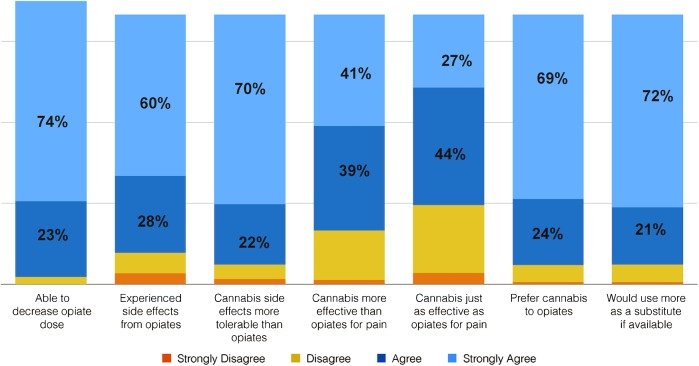

A 2017 study surveying 2800 patients found that 93% preferred using cannabis over opioids for managing pain.1 Of those surveyed, 97% were able to decrease their dependence on opioids through the introduction of cannabis, and 80% described cannabis as being more effective than opioids (Figure 1). Similarly, a retrospective study conducted in 2016 found that the use of cannabis was associated with a 64% decrease in opioid use over a 2-year period.2

Figure 1. Survey: Cannabis with or without Opioid Pain Meds1

While these numbers are impressive, important questions still remain. What makes cannabis so profoundly beloved among people using it for pain management? Is it as clinically effective as its adherents believe? What is the basis for its clinical effectiveness? How should it ideally be used, if psycho-activity can become an impediment to daily activity?

Ayurvedic Perspective on Cannabis Use

Because cannabis has been suppressed in both India and the United States due to its socially and culturally adverse reputation, I was surprised to learn about its significant use in traditional Ayurvedic formulas. Bhavaprakasha, a 14th-century Ayurvedic text, describes cannabis as a medicine with warming and soothing qualities.3 These qualities mitigate the effects of excess Vata, which presents with painful and spastic symptoms, and they alleviate the Kapha quality, which is associated with inflammatory fluid retention, lymphatic congestion, and appetite suppression.3 Bhavaprakasha indicates cannabis use for abdominal cramping, severe pain, severe dysentery, inflammatory conditions, excessive fatigue associated with overactivity, and for stimulating the appetite.

However, one of my honorable Ayurvedic mentors, Vaidya Jayarajan Kodikannath, cautions that Ayurveda considers cannabis to be an “Upavishad” herb. This means that it requires appropriate processing and purification to maximize its powerful clinical benefits and minimize its adverse effects. The section below will explore what this concept means in modern scientific and clinical terms.

Bio-Physiological Activity of Cannabis

To begin, we must acknowledge that the cannabis plant contains up to 70 phytocannabinoids.4 To put this in perspective, we are only now starting to grasp the breadth of the effects that just 3 of these compounds have in the body. These are tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), delta-9-tetrahydrocannabivarin (Δ9THC), and cannabidiol (CBD).

These 3 compounds interact with and affect the body through cannabinoid receptors (CB1 and CB2). The stimulation of either of these receptors has an antinociceptive effect, which ultimately produces the therapeutic benefit of cannabis.5 CB1 receptors are primarily located centrally in the nervous system, in locations such as the thalamus, amygdala, cerebellum, etc, as well as peripherally in the dorsal root ganglia of the spinal cord.5 CB2 receptors are located at the peripheral afferent nerves on the surface of the skin, in the digestive tract, etc, as well as in immune cells like macrophages and macroglia, which perform surveillance and modulate immune responses.6 In summary, CB1 activity is more concerned with the response of the central nervous system to perceived pain, inflammation, injury, etc, while CB2 activity is more concerned with mitigating peripheral perception and immune responses to pain, inflammation, injury, and other triggers of nociception.

There is significant upregulation of CB1 and CB2 receptors in response to neuropathic pain, as well as with inflammatory conditions. THC and Δ9THC bind strongly to CB1 receptors and act as only partial agonists of CB2 receptors. Thus, these compounds contribute to antinociceptive activities centrally and in the periphery primarily through CB1 receptor binding.4 Both have strong psycho-activity. By contrast, CBD binds relatively less effectively to CB1 receptors and has no psycho-activity. CBD has high binding potency to CB2 receptors. It binds strongly enough to have very beneficial health effects and contributes nociceptive activity similar to that of Δ9THC.4 In addition to pain management, CBD conducts immune modulation to reduce inflammation.7

Clinical Indications

Indications for the clinical use of cannabis have become clearer with a growing body of research on the biochemical and physiological effects of cannabinoids. For example, the activation of CB1 receptors in the central nervous system modulate stress-induced responses of the nervous system. This activity is associated with lowering the propagation of pain patterns that are centrally generated.8,9 This effect is especially useful for conditions such as multiple sclerosis and chronic regional pain syndrome (CRPS). In addition, because CB2 receptors are upregulated in microglia and peripheral afferent nerves in response to injury, inflammation, and pain, the activity of CB2 receptors helps to control pain, inflammation, and associated edema.6 CB2 activity has also been found to mediate visceral pain through antinociceptive activity in visceral organs.

CBD use is favored in order to avoid the adverse effects associated with the psycho-activity of THC. In other words, CBD provides wide-ranging effects without the perceptual changes and sedative effects associated with THC activity. Furthermore, the benefits of CBD are associated with the following mechanisms of action10:

- CBD generates an anti-inflammatory effect, as indicated by the reduction of interleukin (IL)-6, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-ɑ, cyclooxygenase (COX)-2, and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) expression.

- CBD has an agonistic effect with adenosine A2A receptors, as it downregulates overactive immune cells and reduces collateral inflammatory damage.

- CBD may help control inflammation in the brain by reducing microglial activation, thereby protecting against degenerative changes or the progression of disease.

- CBD’s binding can promote the uptake of intracellular calcium (Ca2+), thus stabilizing immune cells like mast cells and preventing the inflammatory effects of compounds like histamine.

- Ca2+ influx in smooth muscles and skeletal muscles in response to CBD binding of CB2 receptors also helps mitigate spasticity and associated pain.

Clinical Applications

The aforementioned studies and others demonstrate the clinical indications for cannabis in a wide range of painful conditions. Acute pain after surgery, injuries such as tears of ligaments, tendons, muscles, fractures, etc, as well as chronic pain associated with neuropathic, inflammatory, or degenerative conditions, are treatable with cannabis-based preparations.

Table 1. Routes of Administration: Pharmacodynamic Study of Various Modes11,12

| Mode of Administration | Time of Onset | Length of Effect |

| Smoke/Vapor inhalation | A few seconds | 30 minutes-2 hours |

| Oral ingestion | 1-2 hours | 4-6 hours |

| Transdermal | 1.5 hours | 6-8 hours |

Ideal routes of administration can change depending on the symptoms and conditions being treated with cannabis. For pain, some simple rules can be applied, based on the effect being sought:

- Smoke/vapor inhalation is most useful when the individual is seeking immediate relief from the acute or sudden onset of painful aggravations and muscular spasms. This mode is also effective for individuals seeking antiemetic effects for symptoms associated with conditions such as hepatitis C, migraine, etc.

- Oral ingestion of oil-infused extracts of cannabis proves most beneficial in chronic pain conditions. Orally ingested, oil-infused preparations have a slower onset but provide longer-term relief from symptoms. Oil-infusion also allows cannabinoids to be more easily absorbed across fatty membranes and retained longer. Because of this longer retention, oil-infused preparations only need to be taken 2-3 times per day to treat and control pain.

- Transdermal applications are most helpful for superficial pains and injuries of musculoskeletal tissue, local joint pain and swelling, etc.

CBD vs THC

CBD is by far the most frequently recommended form of phytocannabinoid in my practice. CBD offers the benefit of activating both CB1 and CB2 receptors, and it provides an additive effect by promoting the efficacy and concentration of endocannabinoids.4 Additionally, it is much more practical than cannabis for regular use, since in contrast to THC, CBD does not have psycho-activity. CBD is, by far, the preferred choice of everyone who values sobriety.

On the other hand, I have found that the psycho-activity associated with THC can be useful in the management of severe, debilitating pain that cannot be completely controlled by CBD. THC is effective in conditions where sedation and distraction are important methods of helping to control pain. Relevant conditions might include cases of late-stage cancer, kidney failure, traumatic brain injury, hepatitis, etc.

Combining Cannabis with Other Herbs

While CBD is profoundly effective in helping to control and manage symptoms of chronic pain, it also allows the body to come out of the persistent shock of these symptoms. It brings about welcome changes in clients’ emotional experience and physical energy. By revitalizing them, their vital force becomes available for deeper healing. The subsequent introduction of herbs can then provide an additive and sustaining effect to the healing process.

- Curcuma longa: Curcumin (or turmeric) serves as an effective inflammation modulator by controlling inflammatory pain and swelling. Ayurvedic medicine indicates its use for Kapha-Pitta aggravation, which is demonstrated by the hallmarks of inflammation (rubor, calor, dolor, and tumor). Curcumin is also indicated for ulcers and diseases of the skin.13 A proven medicine for its efficacy in controlling inflammation propagated by COX-2 and TNF-ɑ, curcumin serves as an excellent supportive treatment for conditions including ulcerative colitis, rheumatoid arthritis, pancreatitis, cancer, and more.14

- Boswellia serrata: Boswellic acid alkaloids from frankincense resin have powerful effects on controlling inflammation. In Ayurveda, it is a prescribed for Vata/Kapha-predominant conditions that feature degenerative changes to musculoskeletal tissue and bowels.15 Boswellia has proven clinical benefits for conditions including Crohn’s disease, collagenous colitis, osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and more.16

- Withania somnifera: In Ayurveda, ashwagandha is described as a Rasayana (rejuvenating) herb, indicating its benefit for restoring and stimulating the vital force. Chronic and severe pain have a physically and emotionally draining effect. When an individual is in pain and is still trying to be active, it can “feel like a battle every day,” as one client described it. Adrenal adaptogens, in general, can be very supportive as an individual recovers his or her vitality. Ashwagandha has clinically-proven efficacy for managing stress. In a study of individuals with workplace stress, ashwagandha lowered the percentage of subjects with high serum cortisol levels (15.6-21.5 µg/dL) from 75% to just 15%.18 This study also showed that the herb improved sleep quality, as well as subjective parameters such as irritability, depression, and motivation to work.

Conclusion

While our scientific understanding of the clinical application of cannabis is still nascent, there is a growing urgency to explore responsible clinical use of the herb. The great ingenuity of cannabis plant growers and processors contributes to the availability of CBD-rich plants and extracts, which can be prepared and used without fear of psycho-activity and impairment. A growing body of research supports the use of cannabis in inflammatory, painful, degenerative, and neurological conditions, and it can also play a significant role in alleviating psychological conditions associated with PTSD, anxiety, mania, schizophrenia, and more.

References:

- Reiman A, Welty M, Solomon P. Cannabis as a Substitute for Opioid-Based Pain Medication: Patient Self-Report. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 2017;2(1):160-166.

- Boehnke F, Litinas E, Clauw DJ. Medical Cannabis Use is Associated with Decreased Opiate Medication Use in a Retrospective Cross-Sectional Survey of Patients with Chronic Pain. J Pain. 2016;17(6):739-744.

- Bhava Mishra. Chapter 6: Haritakivarga, Verse 233-234. In: K.R. Srikantha Murthy, ed. Bhavaprakasha. Varanasi, India: Chowkhamba Krishnadas Academy; 2016.

- Pertwee RG. The diverse CB1 and CB2 receptor pharmacology of three plant cannabinoids: Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol, cannabidiol and Δ9-tetrahydrocannabivarin. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153(2):199-215.

- Guindon J, Hohmann AG. The endocannabinoid system and pain. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2009;8(6):403-421.

- Anand P, Whiteside G, Fowler CJ, Hohmann AG. Targeting CB2 receptors and the endocannabinoid system for the treatment of pain. Brain Res Rev. 2009;60(1):255-266.

- Walker JM, Hohmann AG. Cannabinoid mechanisms of pain suppression. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2005;(168):509-554.

- Rog DJ, Nurmikko TJ, Friede T, Young CA. Randomized, controlled trial of cannabis-based medicine in central pain in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2005;65(6):812-819.

- Langford RM, Mares J, Novotna A, et al. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study of THC/CBD oromucosal spray in combination with the existing treatment regimen, in the relief of central neuropathic pain in patients with multiple sclerosis. J Neurol. 2013;260(4):984-997.

- Burstein S. Cannabidiol (CBD) and its analogs: a review of their effects on inflammation. Bioorg Med Chem. 2015;23(7):1377-1385.

- Grotenhermen F. Clinical pharmacokinetics of cannabinoids. J Cannabis Therapeutics. 2003;3(1):4-51.

- Huestis MA. Human cannabinoid pharmacokinetics. Chem Biodivers. 2007;4(8):1770-1804.

- Bhava Mishra. Chapter 6: Haritakivarga, Verse 196-197. In: K.R. Srikantha Murthy, ed. Bhavaprakasha. Varanasi, India: Chowkhamba Krishnadas Academy; 2016.

- Jurenka JS. Anti-inflammatory properties of curcumin, a major constituent of curcuma longa: a review of preclinical and clinical research. Altern Med Rev. 2009;14(2):141-153.

- Bhava Mishra. Chapter 6: Karpudivarga, Verse 50-51. In: K.R. Srikantha Murthy, ed. Bhavaprakasha. Varanasi, India: Chowkhamba Krishnadas Academy; 2016.

- Ernst E. Frankincense: systematic review. BMJ. 2008;337:a2813.

- Bhava Mishra. Chapter 6: Guduchivarga, Verse 189-190. In: K.R. Srikantha Murthy, ed. Bhavaprakasha. Varanasi, India: Chowkhamba Krishnadas Academy; 2016.

- Ashok GA, Shende MB. A clinical evaluation of anti-stress activity of ashwagandha (Withania somnifera dunal) on employees experiencing mental stress at workspace. Int J Ayur Pharma Research. 2015;3(1):37-45.

Image Copyright: <a href=’https://www.123rf.com/profile_iriana88w’>iriana88w / 123RF Stock Photo</a>

Anup Mulakaluri, ND, AWC, is a naturopathic doctor specializing in Ayurvedic Medicine. Dr Anup’s practice focuses on treating the whole person – body, mind, and spirit. He uses clinically proven natural remedies in treatment. This includes food and herbs, lifestyle and health-promoting daily routines, as well as Ayurvedic detoxification and body therapies. His passion is empowering individuals to transform their life and health. For individuals with chronic diseases, focus is placed on restoring healthy physiology and minimizing pharmaceutical dependence. Dr Anup is the founder and president of Natural Rhythms Integrative Medicine (www.nrimseattle.com), a community-centered, multi-care natural health clinic in the Wallingford/Fremont area of Seattle, WA.

Anup Mulakaluri, ND, AWC, is a naturopathic doctor specializing in Ayurvedic Medicine. Dr Anup’s practice focuses on treating the whole person – body, mind, and spirit. He uses clinically proven natural remedies in treatment. This includes food and herbs, lifestyle and health-promoting daily routines, as well as Ayurvedic detoxification and body therapies. His passion is empowering individuals to transform their life and health. For individuals with chronic diseases, focus is placed on restoring healthy physiology and minimizing pharmaceutical dependence. Dr Anup is the founder and president of Natural Rhythms Integrative Medicine (www.nrimseattle.com), a community-centered, multi-care natural health clinic in the Wallingford/Fremont area of Seattle, WA.