David J. Schleich, PhD

Not long after Lust and his colleagues began establishing naturopathic medicine in America, the American Association of University Professors (AAUP) began advocating for academic freedom. A foundational element of this notion is the idea of tenure. Tenure provides job security for teachers and researchers after the successful completion of a period of evaluated probationary service. Only adequate cause, most often coupled with a faculty committee hearing on an academic dismissal, can break such a contractual relationship. The AAUP has been diligent over the years to explain and justify their take on tenure. Their work began back in 1925 with the Conference Statement on Academic Freedom and Tenure. Then came the AAUP’s 1940 Statement of Principles on Academic Freedom, essentially a reworking of the original document. In late 1989 and early 1990, the text of the document changed yet again, the refinements intended to reflect the shifting economic and political nature of higher education in America. Naturopathic educators will find the history fascinating and relevant.

The Notion of Academic Freedom

As our ND programs continue their unrelenting growth, the notion of “academic freedom” has remained a part of the conversation equation, even though there are those, often not in “academe”, who are inclined to take issue with what gets shelf space in the curriculum and what does not. Many elders in the profession, for example, lament the diminution or even disappearance of nature-cure from both the didactic and clinical education learning outcomes. At the same time, there are many recent and not-so-recent graduates who worry that current students are not well enough prepared for a primary care role in those states where regulation permits it. Invariably, the professors and deans in the schools and programs get to call the shots, albeit with a tenuous and sometimes short leash from the CNME, and always with the annual budget’s winged chariot hurrying near.

From the outset, the AAUP grounded its understanding of academic freedom on the idea of “advancing truth.” I’ve heard some of our teachers ask, “What is the ‘truth’ of naturopathic medical knowledge, though?” Is it historically-derived, or should it emerge from an active research and contemporary practice agenda, which, still others insist, is increasingly and dangerously aligned with biomedicine? Where does tenure fit in such a debate, along with the other main ingredient in any potential implementation, ie, cash flow?

As the AAUP explains:

Tenure is a means to certain ends; specifically: (1) freedom of teaching and research and of extramural activities, and (2) a sufficient degree of economic security to make the profession attractive to men and women of ability. Freedom and economic security, hence, tenure, are indispensable to the success of an institution in fulfilling its obligations to its students and to society.

(www.aaup.org/report/1940)

Indeed, the AAUP definition constitutes a reasonable and enabling framework for action for naturopathic medical colleges in the quest to recruit, retain and support good teachers. AAUP leaders explain:

- Teachers are entitled to full freedom in research and in the publication of the results, subject to the adequate performance of their other academic duties; but research for pecuniary return should be based upon an understanding with the authorities of the institution.

- Teachers are entitled to freedom in the classroom in discussing their subject, but they should be careful not to introduce into their teaching controversial matter which has no relation to their subject. Limitations of academic freedom because of religious or other aims of the institution should be clearly stated in writing at the time of the appointment.

- College and university teachers are citizens, members of a learned profession, and officers of an educational institution. When they speak or write as citizens, they should be free from institutional censorship or discipline, but their special position in the community imposes special obligations. As scholars and educational officers, they should remember that the public may judge their profession and their institution by their utterances. Hence they should at all times be accurate, should exercise appropriate restraint, should show respect for the opinions of others, and should make every effort to indicate that they are not speaking for the institution.

(www.aaup.org/repport/1940)

Given these descriptors, should we be striving to create tenure opportunities for our faculty? Should academic administrators have parallel appointments as professors, also with access to tenure? If a potential YES is in the works in our world, what, then, are the major barriers to tenure for the academic officers (faculty, research, administration) of our naturopathic medical colleges and programs in our labor-contracting policies and practices?

Barriers to Tenure

The literature is abundant on the matter (Metzger, 1965; 10th edition of the 1915 Declaration; Pollitt and Kurland, 1998; Academe, 1989 and 1998; McPherson and Schapiro, 1999). These questions are well known to us, and despite the fact that full-time, ongoing, tenured faculty numbers are in decline, these questions will not easily go away. In the case of naturopathic medical colleges, there is no tenure system in place, despite our use of terms such as “full-time,” “permanent,” and “regular staff,” which appear in budget lines that assign allocations to the cost of instruction. Our teachers, the full-time ones and the part-time ones, are, in fact, contractors, usually in segments of time which recur. Even though we pay respect to long service, it is rare in our many “at will” states to consider the employment arrangement any differently.

Academic Freedom and Authority

That same literature about academic freedom, and the related tenure concept, boils down to what McPherson and Schapiro noted a decade and a half ago when commenting on issues of authority in higher education and how it relates to tenure, a conversation which persists as debate in modern higher education:

Much current debate about tenure actually centers on issues of authority in the management of universities. Resolution of the tenure issue will determine how much of a voice faculty members have in key institutional matters such as:

- Who should teach and conduct research?

- What subjects should be taught and investigated?

- How should teaching and research be conducted, including issues such as class sizes, teaching loads, and research expectations?

(McPherson and Schapiro, 1999, p. 20)

Some of our educational leaders argue that tenure unnecessarily strengthens faculty influence on institutional decisions at a time when there is little, if any, “give” in finances and little experience with shared governance of the type that is prevalent, say, in California higher education. In the naturopathic educational world, where the statement of cash flows and the undulations in revenue streams are constantly at the gates of the naturopathic city (just the same as they are in publicly supported institutions or multi-program, comprehensive colleges with long endowment and capital acquisition histories), the financial implications of reduced flexibility in staffing complement allocation are not popular and would be politically tough to implement.

However, that equation referenced earlier, has other influencing factors and elements. The quality, retention, and support of faculty are inextricably bound up in matters of funding academic research, classroom teaching, and curriculum development, but also are affected by the arc of time involved in evaluating such work, which is often long-term in nature. At the same time, and most particularly in the naturopathic environment where the operational costs of significant research enterprise are simply not easily set aside from limited budgets because of the economies of scale under which we operate, the tenure option to support the research agenda often does not get shelf space in the budget process or in longer-term strategic planning. We are so necessarily attentive to “credit hours” and the immediate needs of students that we often just can’t get to it, much less afford it.

Similar pressures come at us from the accreditation realm. The AAUP, for example, recently protested the accreditation of an online institution in this era of MOOCs (massive open online courses) and millennials, and in an era when time-place-bound learning is not only expensive, but under assault from alternative methodologies which many argue make better, more convenient use of the learner’s time. Faculty workload routinely factors into this conversation, as the pressure for research is juxtaposed with the urgent work of teaching, with its attendant challenges of curriculum design and professional formation.

There is, too, the matter of hiring and promotions, and the related matter of collective bargaining (not present in our colleges), which can be affected by a tenure system that influences the expectations and workloads of continuously renewed contractors and recent graduate-employee labor, often expressed in the form of institutional residencies. There is an impact, too, on contingent faculty appointments (also known as “adjunct faculty”). Repeated use of limited adjunct assignments can harm quality, even though, as some argue, it often serves the needs of scarce faculty who want to maintain a strong, personal clinical career path at the same time that they love to teach. Additional issues which intersect with the matter of tenure include matters of copyright, intellectual property in an era of online learning, diversity objectives, and related concerns about discrimination and professional ethics.

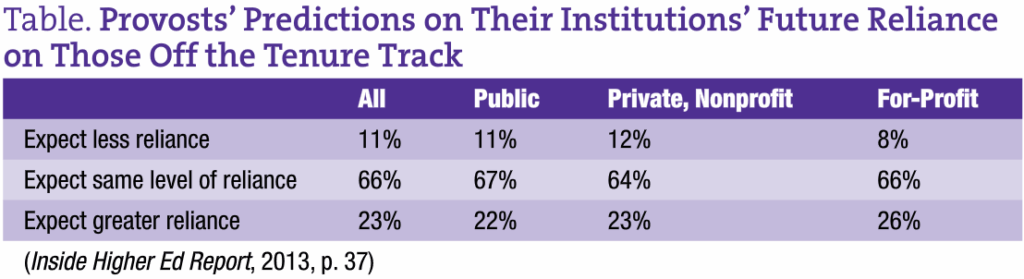

The Nation’s Provosts Weigh In

In such a climate, perhaps the recent book, The 2013 Inside Higher Ed Survey of College and University Chief Academic Officers, provides some light for the path ahead. The report is a great read, based on responses from 1081 college and university provosts, and is strengthened by Gallup’s calculation of a 2.4-percentage-point margin of error for its outcomes. In a nutshell, these academic leaders report that faculty careers are in flux and that future generations of faculty in the US should not expect tenure to be available.

These academic leaders have strong opinions about the role of faculty in their institutions, with or without the tenure option. The survey is very telling:

- Only 8% of provosts strongly agree that their faculty members understand the financial challenges facing their institutions.

- Only 3% of provosts strongly agree that faculty unions benefit higher education, with the figure at 4% at public institutions (where many have faculty unions) and at 2% at private institutions (where such unions are rare). This question received very high “strongly disagree” responses, with 45% strongly disagreeing with the statement.

- Relatively few provosts believe that faculty members can earn tenure based on research success if they are poor instructors. Only 2% strongly agreed, and 5% agreed with that statement.

(Jashik, 2013, www.insidehighered.com/news)

There is little doubt that tenure, as an HR policy and priority, is not soon to be part of the naturopathic medical education context. However, if we are to grow our capacity for generating new doctors in a quest to expand the profession in the era of the Affordable Care Act, we will come face to face with this challenge more than once.

David Schleich, PhD is president and CEO of NCNM, former president of Truestar Health, and former CEO and president of CCNM, where he served from 1996 to 2003. Previous posts have included appointments as vice president academic of Niagara College, and administrative and teaching positions at St. Lawrence College, Swinburne University (Australia) and the University of Alberta. His academic credentials have been earned from the University of Western Ontario (BA), the University of Alberta (MA), Queen’s University (BEd), and the University of Toronto (PhD).

David Schleich, PhD is president and CEO of NCNM, former president of Truestar Health, and former CEO and president of CCNM, where he served from 1996 to 2003. Previous posts have included appointments as vice president academic of Niagara College, and administrative and teaching positions at St. Lawrence College, Swinburne University (Australia) and the University of Alberta. His academic credentials have been earned from the University of Western Ontario (BA), the University of Alberta (MA), Queen’s University (BEd), and the University of Toronto (PhD).

References

- (2006). 1940 Statement of Principles on Academic Freedom and Tenure. Retrieved from http://www.aaup.org/file/principles-academic-freedom-tenure.pdf

- Metzger, W. P. (Summer, 1965). Origins of the Association. AAUP Bulletin, 51(3), 229-237.

- 1915 Declaration of Principles on Academic Freedom and Academic Tenure. Policy Documents and Reports, 10th edition. 291-301.

- Pollitt, D. H. and Kurland, J.E. (July-August, 1998). Entering the Academic Freedom Arena Running: The AAUP’s First Year. Academe,84(4), 45-52.

- (May-June, 1989). 75 Years: A Retrospective on the Occasion of the Seventy-fifth Annual Meeting. Academe, 75(3), 1-33.

- McPherson, M.S. and Schapiro, M.O. (1999). Tenure Issues in Higher Education. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 13(1), 85-98.

- Jaschik, S. and Lederman, D. (January 23, 2013). Skepticism About Tenure, MOOCs and the Presidency: A Survey of Provosts. Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved from insidehighered.com/news/survey/skepticism-about-tenure-moocs-and-presidency-survey-provosts.