Michael Jawer

Rick Brinkman, ND

It is well recognized that many medical treatments – whether conventional or alternative – don’t work equally well for everyone. One person may respond better to a given protocol than someone else doing the identical protocol; one person may return to good health whereas someone else, who had the same symptoms and followed the same advice, does not. Naturopathic physicians know that when treating the whole person, the individualized nature of our physical and emotional well-being becomes plain.

Why should this be? The easy answer is that, since people differ by age and sex, have different lifestyles, significantly different habits and occupations (a high-stress job, for example), their health outcomes will naturally be different. But even when those variables are controlled – that is, when experiments compare people who are very similar in these respects – we still find unexpected differences in outcome. An example is the placebo effect. Scientists find that some people respond incredibly well to a sugar pill or another “sham” treatment; their symptoms will abate or disappear entirely. Other people, matched so there are no obvious differences, derive little or no benefit. No one quite knows why. While both nature (genetics) and nurture (environment) are presumed to play a role, the gap in understanding represents a major challenge in placebo research.

A Shift in the Landscape

Fortunately, attitudes are changing. In fact, the significant ways that people differ – their degree of introversion or extroversion, their general outlook on life, their ease in expressing emotion, their degree of bodily awareness, their susceptibility to stress and infection, their openness to experience, their resilience to life challenges – are, collectively, the hottest topic in psychology and behavioral science.

The time has clearly come for society to move beyond “one size fits all” medicine. This is how we might characterize a medical system that puts each of us into a box based on the disease or disorder we have and the diagnosis or treatment that is expected to always work for us. That nearly half of all Americans have sought out various integrative approaches speaks to people’s rising frustration with conventional medicine and their desire for their treatment options to better align with their individual needs, outlooks – and, yes, personalities.

Feelings and Personality

“Personality” is the word that best sums up what we mean when we talk about individual differences. The accumulation of those differences is, after all, what distinguishes one person most meaningfully from another within a given society or culture.

A useful definition of personality is the following, courtesy of The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language: “a person as the embodiment of distinctive traits of mind and behavior.” This definition captures an extremely important (though woefully overlooked) aspect of ourselves: that we are embodied. The fact that each of us is embodied means that we have a “me” that is distinct from the world around us. The physical boundary between “me” and “not me” literally defines the individual as a living being, and provides the foundation for our unique personalities.

What else is essential to personality? You might offer, “my thoughts, my memories, my consciousness” – and you’d be right. But as science has delved into what it means to be human, it has made a curious discovery: that what underlies our consciousness is our sentience, our capacity to feel. As the novelist Milan Kundera once said of Descartes’ famous dictum, “I think therefore I am,” “‘I think, therefore I am’ is the statement of an intellectual who underrates toothaches.”1 And it’s true. We now know that the brain is but 1 player (albeit a highly important one) in a bodily troupe where biochemical messages circulate everywhere, instantaneously. The brain is on the receiving end of messages from elsewhere in the body as often as it’s the sender. So, what our senses perceive and what we ultimately feel is very much an embodied affair. Descartes, it turns out, was mistaken. His famous dictum is more accurately put as follows: “I feel, therefore I am.”

If personality is a matter of feeling, so feeling is a matter of energy. The very word emotion conveys the energy that we can feel in our bodies. (The word derives from the Latin emovere, meaning “to move from” or “to move out of.”) While this energy ebbs and flows as we go through our day – and inevitably varies as we go through up or down periods in our life – we feel something as long as we’re alive. We are literally animated, and we feel accordingly.

Boundaries: A Key Concept

An enormously useful way to connect personality differences with health is the concept of boundaries. Developed by Dr Ernest Hartmann of Tufts University, this framework allows us to understand why one person may develop one type of chronic illness while someone else develops another – and why a given treatment works better for one person than another.2

Boundaries are a means to appraise the characteristic way a person operates in the world, based on how that person handles the energy of feelings. To what extent are stimuli let in or kept out? How are an individual’s feelings processed internally? The concept of boundaries offers a window into perhaps the most fundamental way that we function as human beings.

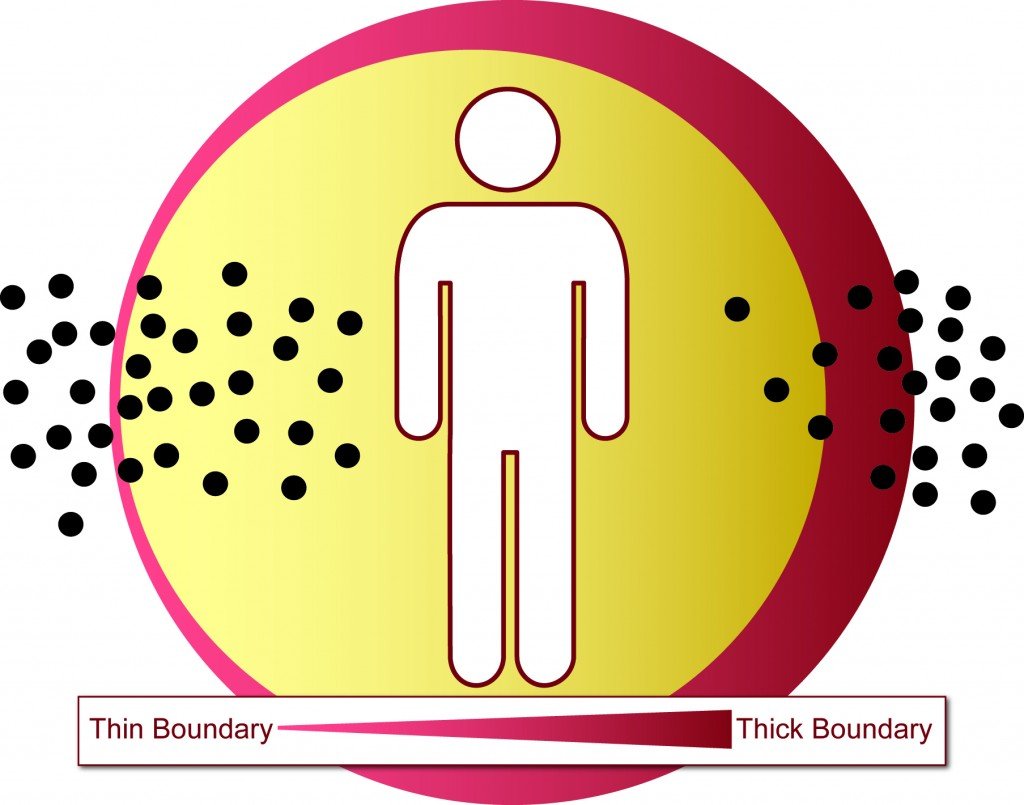

According to Hartmann, each of us can be characterized on a spectrum of boundaries from thick to thin (see Figure). People who have thick boundaries strike us as solid and well organized; they keep everything in its place. They may seem rigid, even armored; we might remark that they are “thick-skinned.” People who have thin boundaries, on the other hand, strike us as especially sensitive, open, empathetic, or vulnerable. In their minds, things are relatively fluid. We might say that they are “touchy” or “thin-skinned.”

The concept is particularly useful in illustrating how individuals differ in their emotional style. Thick-boundary people tend to be calm, stoic, or persevering; they don’t emote easily and will often suppress or deny strong feelings. Indeed, feelings for them are something like a foreign language.

The situation is much different for thin-boundary people. Their feelings flow easily and may present as a volatile mix. They also tend to be highly empathetic, responding strongly to physical and emotional pain and distress, in others as well as themselves.

Since the 1980s, at least 5000 people have taken Hartmann’s Boundary Questionnaire (BQ), and more than 100 published papers have referenced it. The scores on the BQ are distributed across the spectrum of boundaries in a bell-shaped curve. Women tend to score significantly thinner than men, and older people tend to score somewhat thicker than younger people.3

The Flow of Feeling

The energy of feelings works differently in different in people, depending on where they are along the boundary spectrum. A good way to envision this energy flow is to consider the proposition that feelings are like water. Picture any given feeling as a flow of clear, cold water, rippling through the body, in continuous motion. In people whose boundaries are thinner, that flow is quicker and more direct. An especially thin boundary person will come across as highly sensitive, reactive, even “flighty” because his or her feelings flow quickly through the organism. In contrast, people who have thicker boundaries exhibit a feeling flow that is slower and less direct. An especially thick boundary person will appear aloof, imperturbable, even “dull” because his or her feelings proceed more slowly. Studies show, however, that a thick-boundary person is ultimately affected just as much by what’s happening within – it’s just less immediately apparent.

The resulting differences in health are significant. Evidence suggests that thick-boundary people are more prone to hypertension, chronic fatigue syndrome, and ulcers; whereas thin-boundary people are more susceptible to migraine, irritable bowel syndrome, and allergies. The particular form that a chronic illness takes has much to do with the way the stream of feeling meanders within an individual. In one person, it may pool in a particular locale or ripple over into a tributary. In another person, it may cascade freely. In a third person, the flow may be dammed up. Given that energy is involved in any case, various symptoms (pain, fatigue, immune disorders) may result.

A More Personalized Medicine

Just as various illnesses will affect some people more than others, it makes sense that various holistic treatments will benefit some people more than others. In the book Your Emotional Type (coauthored by Michael Jawer), an analysis is presented of 7 integrative therapies according to boundary type – the first time such an evaluation has been undertaken.4 It turns out that thin-boundary people typically respond well to an imagery-based approach, such as hypnosis. Thick-boundary people, on the other hand, respond well to a more ‘hands on’ therapy such as biofeedback. And, the data show, most everyone can benefit from acupuncture and from a practice such as mindfulness-based stress reduction.

The particular therapies chosen (acupuncture, biofeedback, guided imagery, hypnosis, meditation, stress reduction, and yoga) were selected because these have been extensively studied and are well established as safe and effective. Many other treatments are used by naturopathic physicians, of course, and a similar analysis would presumably disclose which of those work best for people who are of a different emotional type.

The result is true personalized medicine that is far more affordable and obtainable than genetic testing – the model that conventional medicine is moving toward to “individualize” treatments.

Your Emotional Type enumerates a dozen chronic illnesses (the “Dozen Discomforts”) that appear most amenable to treatment by integrative medicine. These include allergies, asthma, chronic fatigue syndrome, depression, fibromyalgia, hypertension, irritable bowel syndrome, migraine, phantom pain, post-traumatic stress disorder, rheumatoid arthritis, skin conditions (eczema, psoriasis), and ulcer. They differ from many diseases in that they are rooted in one’s emotional biology. The Dozen Discomforts are constitutional; they directly relate to how the energy of feelings works within us.

Allopathic medicine, which fundamentally views sickness as originating outside the person, fails in many cases to successfully treat chronic pain and illness. Naturopathic medicine, however, can often do so. By knowing your patients’ boundary types and understanding how it relates to chronic illness, you have the power to select the therapies most likely to benefit them.

Further information is available at www.youremotionaltype.com. The Boundary Questionnaire (BQ) is posted there; results of the 18-question quiz are tallied automatically so that individuals can see where they fall on the boundary spectrum. The BQ typically takes less than 10 minutes to complete and score.

Michael Jawer serves as Director of Government and Public Affairs for the American Association of Naturopathic Physicians. He has been investigating the mind-body basis of personality and health for 15 years. Jawer’s articles and papers have appeared in Spirituality & Health, Explore: The Journal of Journal of Science and Healing, Noetic Now, and Science & Consciousness Review. He has spoken before the American Psychological Association and been interviewed by Psychology Today and Advances in Mind-Body Medicine. With Marc Micozzi, MD, PhD, he wrote The Spiritual Anatomy of Emotion (Park Street Press, 2009) and Your Emotional Type: Key to the Therapies that Will Work for You (Healing Arts Press, 2011).

Michael Jawer serves as Director of Government and Public Affairs for the American Association of Naturopathic Physicians. He has been investigating the mind-body basis of personality and health for 15 years. Jawer’s articles and papers have appeared in Spirituality & Health, Explore: The Journal of Journal of Science and Healing, Noetic Now, and Science & Consciousness Review. He has spoken before the American Psychological Association and been interviewed by Psychology Today and Advances in Mind-Body Medicine. With Marc Micozzi, MD, PhD, he wrote The Spiritual Anatomy of Emotion (Park Street Press, 2009) and Your Emotional Type: Key to the Therapies that Will Work for You (Healing Arts Press, 2011).

Rick Brinkman, ND is a 1980 graduate of NCNM and best known for his Conscious Communication® and Life by Design expertise conveyed to millions of people via keynotes and trainings. His clients have included the astronauts at NASA, LucasFilm, Carolina Healthcare Systems, and many more. Dr Brinkman is the coauthor of 5 McGraw Hill books that have been translated into 27 languages, including Life by Design, and Dealing With People You Can’t Stand. Dr Brinkman is president of the New York Association of Naturopathic Physicians, and in 2013 received the AANP President’s Award in recognition of his longtime support for the mission and vision of the American Association of Naturopathic Physicians.

Rick Brinkman, ND is a 1980 graduate of NCNM and best known for his Conscious Communication® and Life by Design expertise conveyed to millions of people via keynotes and trainings. His clients have included the astronauts at NASA, LucasFilm, Carolina Healthcare Systems, and many more. Dr Brinkman is the coauthor of 5 McGraw Hill books that have been translated into 27 languages, including Life by Design, and Dealing With People You Can’t Stand. Dr Brinkman is president of the New York Association of Naturopathic Physicians, and in 2013 received the AANP President’s Award in recognition of his longtime support for the mission and vision of the American Association of Naturopathic Physicians.