David Schleich, PhD

Within days of my joining the naturopathic community in Canada in late 1996, Dr. Lois Hare, then president of the Canadian Naturopathic Association (known these days as the Canadian Association of Naturopathic Doctors) called from Nova Scotia to encourage our fledgling school in Toronto to train its graduates to do research. Dr. Hare imagined bench- and practice-based research being as common to the profession as its abiding protection of nature-cure traditions.

In the ensuing decade, the work of individual naturopathic scholars and the profession-wide mission of the Naturopathic Medicine Project have generated a sustained commitment to systematically establish and proliferate a theory of naturopathic medical knowledge. The energy spinning out into the profession from those theorists, writers, clinicians, teachers and writers is not unlike what must have been happening in the early part of the last century. During those early decades, there appeared year after year an abundance of journals, articles, pamphlets and books expounding on every nook and cranny of naturopathic medicine. Today’s flowering continues this work, articulating in an ongoing way the methods of naturopathic medicine and validation not only for the profession, but also for its students and other health professionals. This is the very stuff of an epistemology of naturopathic medicine taking place before our very eyes and in our time.

The Whole is Greater Than its Parts

Many naturopathic scholars assert that the gestalt (or organized whole) of naturopathic medical knowledge truly accumulates into an epistemology that is greater than any of its major parts. There are debates and conversations about those parts. A recurrent conversation, for example, centers on biomedical knowledge, which the allopathic professions claim inappropriately as their own. No one doubts that it, too, is largely theoretical, despite its pragmatic manifestations, in that it comprises the knowledge and research conjugated through fields such as human and veterinary medicine, and odontology (to name a few), as well as through fundamental biosciences, including biochemistry, biology, chemistry, embryology, histology, genetics, pathology, microbiology, botanics and so on.

The historical record, however, also demonstrates that biomedicine is less concerned about the whole of its nature being greater than the sum of its parts, and appears to be more focused on the theory, knowledge and research of medicine than on the actual practice of medicine, much less on its philosophical assumptions. Indeed, NDs frequently report that their biomedicine counterparts don’t often question the paradigm of their own medical model, maintaining more often that their medicine is properly focused on establishing potential new drugs or on deeper, molecular understanding of the mechanisms underlying disease. In fact, they’re sure that biomedicine lays the foundation of all medical application, diagnosis and treatment. All too often, they are surprised by how much we know about their foundation.

Baer (1987, 1992, 2001) reminds us that biomedicine is merely the heterodox version of a medical system that he labels as the “American dominative medical model.” Biomedicine is socially, economically and politically positioned for control in our time; however, those who consider the terrain of knowledge upon which any system is constructed are not immune from the social anthropologists, historians and political scientists among us looking more closely at the durability of any one group’s assumptions. That a dominant group can be ascendant in one generation and toast the next is not without precedent. In this regard, there are numerous academic conversations that are all about the epistemology we’re considering here, and which it behooves us to learn more about.

For example, some social scientists and medical historians have looked into the theories of knowledge that underlie professions or disciplines and challenge some assumptions and certitudes. As a case in point, Power (2000) surprisingly asserts, “rarely questioned [is] the idea of science as essential to medicine.” Actually, there are scholars such as Wetzler, whose poignant 1984 study with respect to the dominant position of science in the study and practice of medicine pointed out that there are numerous “myths” present in an epistemology that locates science dead center in the validation of a medical system. His list includes the following:

- the myth that educational processes are inherently beneficial

- the myth of the basic sciences, or “physico-chemico-reductionism”

- the myth of excellence, in which standards are supposedly maintained by dubious or at least questionable educational methods and means of assessment

- the myth of the false foundations (that no student can possibly deal with a clinical problem unless he or she has studied “all the basic sciences”) (1984, p. 135)

While it is the topic of another discussion to elaborate on the medical educational processes to which Wetzler alludes by way of comparison with some commentaries about biomedicine and the allopathic world, Richenda Power (2000) provides a remarkable compendium of definitions associated with the “art” and “science” of “holistic medicine” in her book, A Question of Knowledge (2000). The juxtaposition of commentary about the primacy of “science” in theories of knowledge attached to specific medical systems, separated by almost 20 years, is quite instructive for us as we contemplate an epistemology of naturopathic medicine. Whereas Wetzler challenged the unquestioned centrality of science in the study and practice of mainstream, western medicine, Power found “few statements that contained direct claims for holistic medicine being an art” (p. 128), but rather discovered a much larger “representation” of material on the “science” of holistic medicine. She points out, though, that such material was invariably “used as powerful symbolic capital in political struggles between groups of health workers” (p. 129).

This academic conversation constitutes a kind of social-scientific debate and includes reports of statements such as: “there is knowledge other than the scientific”; “we need a new form of science and medicine”; “instinctive common sense and experience are good enough”; and “medicine is not scientific anyway” (Power, 2000).

The Ideal Approach to Wellness

Such discourse has been occurring for many decades, and from various locations in the wider debate about the nature of health and about what is the ideal approach to promoting and sustaining lifelong wellness. Leavell and Clark’s widely circulated 1965 model of prevention is a very good example of this shifting terrain of the debate about which theory is best and why.

Their study, essentially an interpretation of the natural history of disease process, constituted an important element in the larger paradigm of medicine. The model’s intensity gradient has three stages (sub-clinical/unapparent disease; diagnosis; death) very familiar to the ND and allopathic physician. Consistent with the ND’s understanding of the occurrence of disease over time and, thus, the opportunity for prevention is the sequence: prepathogenesis (before the disease occurs), early pathogenesis (small changes in cells and body tissue), demonstrable but early disease (that can be recognized by diagnostic processes or screening), advanced or manifest disease (clearly identifiable) and convalescence (period after the disease has run its course).

Even with this model in mind, NDs are most focused on primary prevention; that is, making people more resistant to infection and slowing the progress of a particular disease via education, supplements and mind/body alignment techniques such as meditation and stress reduction. The allopathic, or biomedicine, doctor, the argument goes, tends to have a different beginning point with patients.

During this same period, another scholar, Nixon (1984), was explaining that what was emerging at the beginning of the 1980s more strongly than in the previous two decades was a “paradigmatic shift” from the reductionism of a strictly biomedical perspective on health to “an integrative, humanistic or holistic approach” (p. 27) that questioned the unassailable position of science in health design and delivery, and also in the education of doctors. Relevant here is the work of Adler and Shuval (1978). Citing them almost a decade later and with the benefit of the work of Nixon, Leavell, Clark and Wetzler, Carpenter (1986) notes that when discussing the education of professionals, medical students report feeling “subject to negative pressures concerning the scientific element in medical training” during their studies. As their training progresses, he explains, the very “centrality of science for medical practice” is of decreasing importance “for the competent physician.” He explains, though, that at the core of scientific medicine are techniques not anathema to naturopathic medicine, such as inspection, palpation, percussion and auscultation.

Both the allopathic and naturopathic doctor look, touch and listen. Both have lab tests and instruments to do the work of physical and clinical diagnoses. Indeed, these similarities have been true from the days of Frederick Gates and William Osler, who anticipated a time when all medicine, natural or scientific, could be “reduced to an exact science” (Bliss, 1999). Osler was declaring as early as 1892 in The Principles and Practice of Medicine that the rigor he and others felt must accompany “scientific” medicine was frequently not present in such fields as naturopathy, homeopathy and osteopathy.

Osler contended that “medicine must rest on science” (Bliss, 1999). Osler as a clinical physician wanted a scientific underpinning to “working at the bedside,” focused on the “whole patient,” not unlike the ND who is trained to develop a relationship with the patient, which includes a comprehensive awareness of the person’s complete physical, spiritual and mental makeup. Boon (1995, 1996), and XXXXX (1986, 1988) before her, have identified the contemporary manifestations of this tension between holistic and scientific practitioners, and indeed between holistic and scientific naturopathic practitioners. The holistic practitioner’s spiritual and physical words are “not separate, but manifestations of a single life force” (Boon, 1996). Consequently, symptoms, whether physical or spiritual, command the same attention. Their scientific counterparts, however, to iterate the epistemology, practice based on a biomedical model, which reduces all pathology to a cellular or molecular level. For the latter, the scientific method is the route to curing a disease. For the former, environment and spiritual balance are key factors in a treatment protocol.

As Schon reports (1994), though, despite the philosophical paradigm of any one group’s location in either an orthodox or heterodox medical system, “the greater one’s proximity to basic science, the higher one’s academic status.” Professional schools of medicine, in such a context and within such an epistemology, would strive to train healers and socialize them as biotechnical problem solvers. Routinely, they would follow a sequence that immersed the student in medical science and then in supervised clinical practice. Glazer (1974) describes this approach as a “yearning for the rigor of science-based knowledge and the power of science-based technique.” This fascinating polarity hugely influenced the development of naturopathic medical education in North America. The existence of a distinct tension between professional orientation (itself not consistent across the profession and often regionally diverse) and student socialization has been discussed from a somewhat different perspective by Boon (1996) in her analysis of the scientific and holistic world views of both students and practitioners.

Gieryn’s (1983) discussion about the practical problem of constructing some kind of boundary between science and “varieties of non-science” is an important theoretical discussion about the claims to authority that science insists upon. NDs and their teachers seem attracted to such a source of authority, but define their eclectic professional therapies inside and outside such boundaries. There are even continuing claims that the profession has not embarked on rigorous research about key modality areas in its repertoire, such as individualized nutritional therapy (Vickers and Zollman, 1999) or chronic diseases in general (Haynes, 1999). A persistent equivocation in the broader field of clinical practice and the continuing influence of practitioners on their educational institution’s priorities have influenced the development of the profession and those very educational institutions that prepare them for practice in a growing number of regulated states and provinces.

Meanwhile, there is the ever-present pharmaceutical industry, alert at the ramparts of public health and health promotion, ever ready to develop medications based on empiric observations and known disease mechanisms. Recent advancements in the genetic etiologies of common diseases will likely continue to improve pharmaceutical development and be of interest to a segment of the naturopathic profession. In this regard, it is fascinating to predict how the emerging notion of “personalized medicine” will take shape in the fuss and rattle of so-called “integrated medicine,” which many of our NDs see in many ways as simply an extension of traditional clinical medicine taking advantage of the cutting edge of genetics research.

The naturopathic profession’s enduring reputation for high-touch patient care coupled with a growing respect for the importance of research is being consistently poked away at, though. For example, a national consortium of medical research institutions, funded through a U.S.-based organization called Clinical and Translational Science Awards (CTSAs), has familiar-looking goals they insist are focused on patients:

- Support a more inclusive medical research agenda

- Improve the way medical research is conducted across the country

- Reduce the time it takes for laboratory discoveries to become treatments for patients

- Engage communities in clinical research efforts

- Train the next generation of clinical and translational researchers

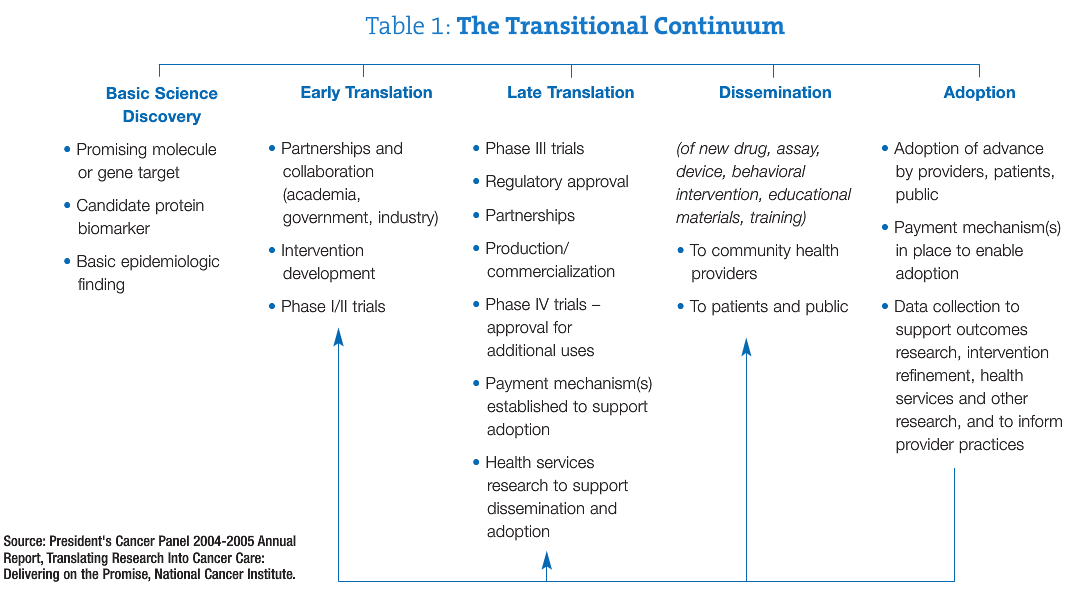

The health industry around us is a well-oiled monolith, some say. Its continuum is well known to the naturopathic profession and more particularly known to our research colleagues interested in advancing the medicine. A typical pathway translates from “basic science” discovery through to “adoption” and demonstrates the complexity and density of the biomedicine framework of North American health systems (see Table 1).

Robert Duggan, cofounder of the Traditional Acupuncture Institute in Columbia, Md., also captures another filament in this tension when he writes: “In Baltimore, Wolfe St. runs between two groups of buildings: The Johns Hopkins Medical School on one side of the street, representing the finest in medical skill and technology, and the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health on the other, symbolizing a humanistic, community-based approach to healthcare. When differences between the two schools were more pronounced than they are now, people joked that Wolfe Street was the widest in the world. Our culture needs a blend of what’s on both sides of that street” (1995, p. 241).

David Schleich, PhD is president and CEO of NCNM, former president of Truestar Health, and former CEO and president of CCNM, where he served from 1996 to 2003. Other previous posts have included appointments as vice president academic of Niagara College, and administrative and teaching positions at St. Lawrence College, Swinburne University (Australia) and the University of Alberta. His academic credentials have been earned from the University of Western Ontario (BA), the University of Alberta (MA), Queen’s University (BEd) and the University of Toronto (PhD).

David Schleich, PhD is president and CEO of NCNM, former president of Truestar Health, and former CEO and president of CCNM, where he served from 1996 to 2003. Other previous posts have included appointments as vice president academic of Niagara College, and administrative and teaching positions at St. Lawrence College, Swinburne University (Australia) and the University of Alberta. His academic credentials have been earned from the University of Western Ontario (BA), the University of Alberta (MA), Queen’s University (BEd) and the University of Toronto (PhD).

References

Adler, J. and J.T. Shuval. (1978). Cross pressures during socialization for medicine. American Sociological Review. 43 (5): 693-704.

Baer, H. A. (1987). Divergence and convergence in two systems of manual medicine: osteopathy and chiropractic in the United States. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 4, 176 – 193.

Baer, H. A. (1992). The potential rejuvenation of American naturopathy as a consequence of the holistic health movement.” Medical Anthropology. 13:369-383.

Baer, H.A. (2001). Biomedicine and Alternative Healing Systems in America: Issues of Class, Race, Ethnicity and Gender. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Bliss, Michael. (1999). William Osler: A Life in Medicine. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Boon, Heather. (1995). The making of a naturopathic practitioner: the education of alternative practitioners. Health and Canadian Society. 3(1/2): 15-41.

Boon, Heather. (1996). Canadian Naturopathic Practitioners: The Effects of Holistic and Scientific World Views on Their Socialization Experiences and Practice Patterns. PhD Thesis, University of Toronto.

Carpenter, P. (1997). The education of professionals. Education and Society. 4(1): 38-51.a

Duggan, R. M. (1995). Complementary Medicine: Transforming Influence of Footnote to History? Alternative Therapies, 1(2), 28-32.

Gieryn, T.F. 1983. Boundary-work and the demarcation of science from non-science: strains and interests in professional ideologies of scientists. American Sociological Review, 48: 781-95.

Glazer, N. 1974. The schools of the minor professions. Minerva, 12(3), 346-363.

Gort, E. (1986). A Social History of Naturopathy in Ontario: The Formation of an Occupation. M.Sc. Thesis, Division of Community Health, University of Toronto.

Gort, E.H. and Coburn, D. 1988. Naturopathy in Canada: changing relationships to medicine, chiropractic and the state. Social Science and Medicine. 26(10): 1061-72.

Haynes, R.B. (1999) Commentary – A warning to complementary practitioners: Get empirical or else. BMJ. 319: 1632.

Leavell, H.R. & Clark, E.G. (1965). Preventive Medicine for the Doctor in His Community. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Nixon, P. (1984). BFI Film and TV Database. Opinions. June 8, 1984.

Osler, W. (1885). The growth of a profession. Canada Medical & Surgical Journal. Vol. 14, 129-155.

Power, R. (2000). A Question of Knowledge. London: Prentice Hall.

Vickers, A. & Zollman, C. (1999). Unconventional approaches to nutritional medicine. British Medical Journal. 319.7222: 1419.

Wetzler, M. (1984). Holistic aspects to medical training. British Journal of Holistic Medicine. April, pp. 55-62.