Joseph Kellerstein, DC, ND

Wendy sat there with a relaxed posture yet bearing a kind of competent look that was always present. This was an unusual impression in a 9-year-old girl.

She presented with her mom, who has been a long-term patient and fan of homeopathy. I greeted her, and when invited to respond to friendly words, her face lights up and out comes a warm response. On glancing down at the intake form, I see only one word—“stomach.”

Wendy has had stomach pain on and off since senior kindergarten. She will cry some mornings because it hurts so much. Most often, it hurts before and after breakfast. Some days, it hurts before and after supper but less often. The pain has been there most days for the past months.

This is all I got during the first 10 minutes. I decided to fish for other concomitant symptoms to round out the picture.

Ultimately, nausea came up with an affirmative response. There was nausea associated with the pain in the stomach.

I hunted for concomitants to the nausea. To my surprise, Wendy proclaims that she feels cold when she is nauseous. A bit further down the road of detailed questioning, I discover that the coldness is emphasized in the arms, especially the upper arms.

Next, I switched questioning tactics to utilize the “second-person projection” idea.

“Wendy, if I saw you when you were very ill with this stomach pain, what would I especially notice about you—what you were doing and how you looked—that is very different from right now?”

Questions like this give the patient a new perspective in providing data by coming outside of themselves in an objective manner to note various differences. A change of frame often yields valuable information.

“I would be sitting bent. My face is pale and clammy. There is a headache. [I ask for details on this new symptom.] The pain is over my right eye and right temple. It is worse if I talk or move.”

As our young patient associates into this painful state to better describe the nature of it, I notice that she is gently rubbing the upper abdomen continually. I note that perhaps this is a useful objective symptom that may be indicative of the needed remedy.

I inquire as to what she is doing with her hand. The answer is that it helps a bit to keep doing this. I confirm that this action is typical of the actual painful state. “Yes, it is,” she replies.

When that tactic was exhausted, I decided to seek the original state of the problem. There was no apparent etiology either in the life of our patient or in the family.

“When it first began, what was it like to have to suffer from this stomach pain? What would happen when it was bad?“ Here, I was seeking the most intense state of the complaint because it is most likely to be rich in descriptors. “If I saw you, what would I see?”

When it first started, it was around midnight (her mom specifies the time). Wendy would awaken and be upset with the pain. She would go into her parents’ room.

I asked why. The response was that she wanted company. Why did she want company? Company seemed to help make the pain better.

This point in the interview nicely engages both Wendy and her mom in the exercise of recalling past states and in eliciting descriptors. Her mom then recalls, “Yes, she would be better soon after coming in. She would also frequently ask for ginger ale when her tummy was upset, and she still does!”

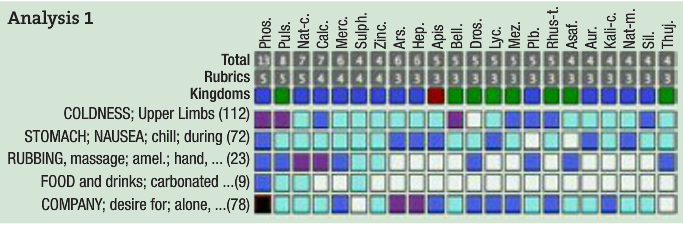

The homeopathic repertory chart strongly indicates that phosphorus should be considered as a first candidate for study. In fact, the need for company, the amelioration from rubbing, and the desire for carbonated beverages confirmed it. I prescribed phosphorus 30C (1 teaspoon per day) in water.

Today is 2 weeks later, and the patient just left my office saying that the pain vanished well within 2 doses and that there has been no hint of this constant companion. Certainly, this fresh case cannot be presented as cured before the 1-year mark. However, the techniques of questioning over and above the regular case-taking panels of questions came into play in arriving at this genius of symptoms.

To comprehend homeopathy, one must practice the methods of Hahnemann with some diligence. Only then does his Organon of the Healing Art come alive and become a useful guide to one’s experience.

In practice, case taking and developing facility with the standard questions are crucial. Once mastered, there are other techniques of assisting the patient in rendering a detail-rich portrait of his or her suffering without venturing to speculation.

In some of our naturopathic colleges, Hahnemann has been judged a fossil. The homeopathic programs have become a fan club to popular new and speculative techniques.

In true academic study, there is scholarship and continuity with the roots of that study. Our young students are being deprived in some schools of a solid methodical foundation in our most important holistic model—Hahnemann homeopathy.

These students never develop any facility for case taking and soon give up on homeopathy. They never had the tools.

Joseph Kellerstein, DC, ND graduated as a chiropractor in 1980 and as an ND in 1984. He graduated with a specialty in homeopathy from the Canadian Academy for Homeopathy and subse-quently lectured there for two years. He also lectured in homeopathy for several years at CCNM; for eight years at the Toronto School of Homeopathic Medicine; and for two years at the British Institute for Homeopathy. Dr. Kellerstein’s mission is the exploration of natural medicine in a holistic context, especially homeopathy and facilitating the experience of healing in clients

Joseph Kellerstein, DC, ND graduated as a chiropractor in 1980 and as an ND in 1984. He graduated with a specialty in homeopathy from the Canadian Academy for Homeopathy and subse-quently lectured there for two years. He also lectured in homeopathy for several years at CCNM; for eight years at the Toronto School of Homeopathic Medicine; and for two years at the British Institute for Homeopathy. Dr. Kellerstein’s mission is the exploration of natural medicine in a holistic context, especially homeopathy and facilitating the experience of healing in clients