Open Pilot Study Using a Liquid Emulsion Form of Cetyl Myristoleate

David Arneson, NMD

Seth Black, NMD

Barry Gelinas, MD

Jeffrey Langland, PhD

Robert Waters, PhD

The objective of this open uncontrolled study was to evaluate the benefit of a novel liquid emulsion form of cetyl myristoleate in patients with clinically diagnosed fibromyalgia (FM). Desiccated oral cetyl myristoleate has been used extensively since 1991 to treat various inflammatory disease states (mostly arthritis). Although FM affects 2% to 4% of the population worldwide, the literature on cetyl myristoleate to treat FM is sparse. Participants in this study were selected based on a previous diagnosis of FM (mean time since diagnosis, 11.89 years), confirmed by interview and by physical examination. Eighteen patients completed the study and were monitored weekly for 4 weeks at The Source Naturopathic Medical Clinic, Phoenix, Arizona, using the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36). Data were analyzed using commercially available statistical software. Paired t tests were used for each of 8 SF-36 categories and an overall composite category. The results demonstrated a significant difference between the pretreatment data and the posttreatment data for each SF-36 category (P < .001 for all). Therefore, a significant treatment effect of liquid cetyl myristoleate was substantiated in patients having FM, with a low probability of error. The mean differences between the pretreatment data and the posttreatment data ranged from 24.23 (for the mental health category) to 56.94 (for the role-physical category), with a positive benefit after treatment for all 8 SF-36 categories. In conclusion, patients treated with liquid cetyl myristoleate showed substantial improvement in all aspects of their FM, including pain reduction, physical well-being, mental functioning, and emotional health.

Hypothesis Criteria

This open uncontrolled study of a novel liquid emulsion form of cetyl myristoleate included 16 women and 2 men with fibromyalgia (FM) (mean age, 52.11 years). The mean time since diagnosis of FM was 11.89 years (range, 1-32 years). The mean number of physician visits per patient after the original FM diagnosis was 143.31. In 1 patient, diagnosed more than 23 years previously, the number of physician visits exceeded 400. The mean number of prescribed medications per patient was 19.89, with 1 patient having been prescribed 70 different medications.

Fibromyalgia affects approximately 2% to 4% of the population worldwide1; it is more common in women than in men. The etiology of FM is unknown, and its pathogenesis is poorly understood. Common symptoms of FM include fatigue, headache, stiffness, depression, irritable bowel, sleep disturbance, cognitive dysfunction, anxiety, coldness, paresthesias, sicca syndrome, exercise intolerance, and dysmenorrhea.2-4 Fibromyalgia compromises physical and emotional functionality, joint mobility, and quality of life, and systemic pain may have an insidious onset.5,6 Many theories have been hypothesized as the cause of FM. Some of the more prevailing ones include cytokine storms, thyroid dysfunction, hypometabolism, serotonin deficiency, mitochondrial dysfunction from oxidative stress, central nervous system pain processing dysfunction, muscle hypoperfusion, and poor nutrient or antioxidant status.7-15

Fibromyalgia is clinically diagnosed based on the presence of chronic widespread pain (reported for >3 months), 11 tender points among 18 specific anatomic sites (bilaterally in the upper and lower extremities, involving the front and back), and the commonly associated symptoms aforementioned.16 It is progressive and over time becomes more debilitating, leading to social withdrawal and physical dysfunction. Individuals with FM are often unable to maintain independence because of their pain levels, decreased mobility, or both. Pain may be the first symptom noticed; therefore, pain management and anti-inflammatory medications are often the therapy of choice and are generally prescribed for symptomatic relief. Although choices for therapy are abundant, little progress has been made in elucidating the cause of FM or its successful treatment.

Nonpharmacological and pharmacological therapies are used to treat FM. Nonpharmacological therapies include nutrition, spinal manipulation, soft-tissue manipulation, trigger point therapy, vitamin supplementation, intravenous therapy, acupuncture, exercise, and physical treatment.17-34 Pharmacological treatments include anxiolytics and hypnotics (alprazolam, clonazepam, zolpidem, and buspirone hydrochloride), central-acting skeletal muscle relaxants (cyclobenzaprine hydrochloride), antidepressants (amitriptyline, duloxetine hydrochloride, and milnacipran hydrochloride), nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (acetaminophen and ibuprofen), anticonvulsants (pregabalin and gabapentin), and antihypertensive agents (clonidine hydrochloride).35

Cetyl myristoleate, a natural fatty acid ester chemically denoted as cis-9-tetradecenoic acid, was originally extracted from Swiss albino mice by Dr Harry W. Diehl in the early 1970s, after 11 years of chemical research; it was reported to demonstrate antiarthritic properties in animal investigations.36 Since early 1991, desiccated oral cetyl myristoleate has been available to the public37 and has been used extensively to treat inflammatory disease states such as arthritis. Early animal research and subsequent use in humans demonstrated few adverse reactions to cetyl myristoleate, including gastrointestinal upset, with increased gas or belching. Animal investigations used an injectable liquid form of cetyl myristoleate, while human delivery included several different chemical entities of desiccated oral forms. Cetyl myristoleic acid is the most effective form, with cetyl oleate demonstrating somewhat less efficacy. Cetyl myristate and cetyl elaidate have been found to be ineffective in the treatment of these inflammatory diseases.36 Cetylated fatty acids have been shown to improve joint function and quality of life, even when applied topically.38,39 The efficacy of cetyl myristoleatese in the treatment of arthritis was corroborated by researchers at the University of Nevada School of Medicine, Reno.40

The exact mechanisms of action of cetyl myristoleate are unknown at this time, but the following theories have been anecdotally proposed: It has been postulated that cetyl myristoleate may have a role similar to that of other fatty acids such as those found in fish oils. Fatty acids of this class are known to block the production of proinflammatory cytokines (prostaglandin series 2 and leukotriene series 4) and to encourage the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines (prostaglandin series 3 and leukotriene series 5). Prostaglandins and leukotrienes are unsaturated fatty acids that regulate local metabolic processes, including inflammation, platelet aggregation, pain, fluid balance, and nerve transmission. It has been reported that myristoleic acid inhibits 5-lipoxygenase in tissue, which understandably would lead to reduced inflammation and pain. It has also been noted that cetyl myristoleate acts as a surfactant that lubricates joints, but this is highly speculative and unproven at this time. Other suggested roles include the incorporation of these fatty acid esters into phospholipid cell membranes and an increase in cell membrane fluidity (a well-known function of fish oil fatty acids), thus altering phospholipid membrane permeability. Cetyl myristoleate has been thought to act as an immunomodulator owing to its anti-inflammatory properties observed in arthritis pain investigations.

While information exists on the treatment of a wide variety of inflammatory diseases using cetyl myristoleate,38,40-42 the literature on cetyl myristoleate to treat FM is sparse. Because of its success in treating other inflammatory diseases, we performed an open pilot study to evaluate the benefit of a novel liquid emulsion form of cetyl myristoleate in patients with clinically diagnosed FM. We hypothesized that liquid cetyl myristoleate would improve physical and mental symptoms of FM, without unwanted or harmful adverse effects.

Methods

The liquid cetyl myristoleate used in this study was produced by a contract manufacturer, certified by NSF International, Ann Arbor, Michigan. The NSF Good Manufacturing Practices Registration for contract manufacturers and internal manufacturing facilities of dietary supplement companies enables contract manufacturers to become independently registered by NSF International, verifying their compliance with Good Manufacturing Practices requirements as listed in Section 8 of NSF/American National Standards Institute Standard 173-2008. These requirements are consistent with the published Good Manufacturing Practices regulation for dietary supplements as defined in 21 CFR §111, which was published by the Food and Drug Administration in May 2007. Good Manufacturing Practices are guidelines that provide a system of processes, procedures, and documentation to assure that a product has the identity, strength, composition, quality, and purity that it is represented to possess. The active ingredient of liquid cetyl myristoleate used herein was standardized to 2250 mg/15 mL (approximately 1 tablespoon).

During a 4-week study period, participants with FM consumed 1 tablespoon (15 mL) of liquid cetyl myristoleate before bedtime and were asked to otherwise maintain their normal daily activities, including consuming their ordinary diet and taking their prescribed medications. At study entry, patients were interviewed in person, completed a health history questionnaire, and signed consent forms at the testing site before evaluation. Participants were required to complete the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) weekly (by phone or office visit), to document ongoing physical and mental changes, and to assess any possible adverse effects. The study was performed at The Source Naturopathic Medical Clinic, Phoenix, Arizona, beginning on March 29, 2010 (when the first patient was interviewed), and ending on June 23, 2010 (when the last patient submitted the SF-36 paperwork).

Patients’ responses on the completed SF-36 questionnaires were statistically and graphically analyzed and included the following 8 categories: physical function, role limitations due to physical health (role-physical), body pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role limitations due to emotional problems (role-emotional), and mental health. Of 21 study participants, 18 patients

(16 female and 2 male) completed the study. The patients excluded from the final analysis did not complete all the SF-36 questionnaires or did not return for follow-up appointments.

Data from the SF-36 questionnaires were analyzed using commercially available statistical software. The statistical model used paired t tests. Participants had been asked to complete an SF-36 questionnaire before treatment and another at least 10 days after treatment. A spreadsheet was used to generate numerical and 3-dimensional graphical data for each of 8 SF-36 categories and an overall composite category. P < .001 was considered statistically significant.

Results

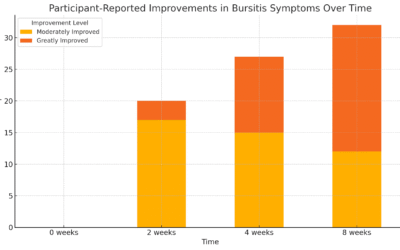

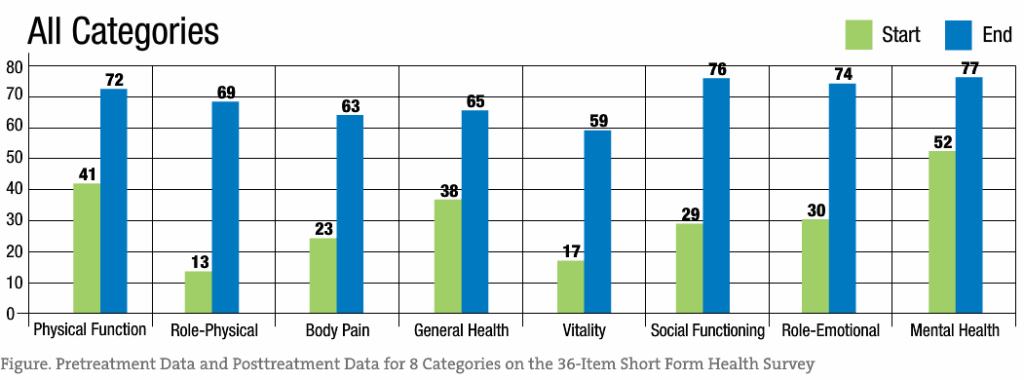

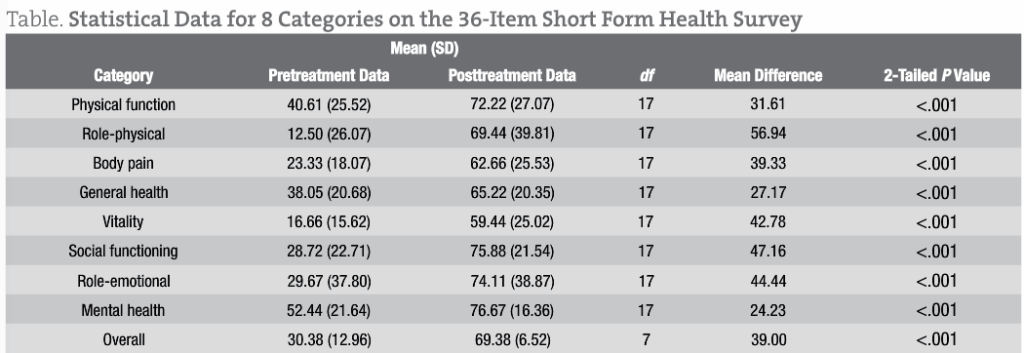

Among the study patients, oral administration of liquid cetyl myristoleate resulted in a significant difference between the pretreatment data and the posttreatment data for each SF-36 category (P < .001 for all). These findings are summarized in the Figure and in the Table.

Significant treatment effects are evident across all SF-36 categories, with role-physical, body pain, vitality, and social functioning demonstrating the greatest response to liquid cetyl myristoleate treatment. While these results support the reduction of pain associated with FM, the other categories showed improvement as well.

Statistical analysis using paired t tests was performed for each of 8 SF-36 categories and an overall composite category (Table). The results demonstrated a significant difference between the pretreatment data and the posttreatment data for each SF-36 category (P < .001 for all). Therefore, a significant treatment effect of liquid cetyl myristoleate was substantiated in patients having FM, with a low probability of error. The mean differences between the pretreatment data and the posttreatment data ranged from 24.23 (for the mental health category) to 56.94 (for the role-physical category), with a positive benefit after treatment for all 8 SF-36 categories.

Assuming 80% power and at least 95% confidence, the theoretical sample size was checked, with an SD of approximately 25 for both the pretreatment data and the posttreatment data. Using a 2-tailed test to determine a 30-point difference in the means between the pretreatment data and the posttreatment data, the estimated sample size requirement would be approximately 11 patients per data group. Our study included 18 patients, which is close to the calculated sample size.

Comment

The major findings of this study were overall dramatic improvements in physical well-being, mental functioning, and emotional health in patients having FM treated with liquid cetyl myristoleate. Several patients reported increased visual acuity and reduced blood pressure. In subjective and statistical analyses, all 18 patients who completed the study had improved on all 8 measures of the SF-36.

The observed pain reduction and improvements in the role-physical, body pain, vitality, and social functioning categories may be multifactorial in origin. These include the effects of liquid cetyl myristoleate on anti-inflammatory pathways, on the fluidity of cellular membranes in signal transmission or waste removal, and on the formation or regulation of serotonin, norepinephrine, and thyroid hormone levels. Based on reports of reduced blood pressure and increased visual acuity by some patients herein, liquid cetyl myristoleate may influence physiological vasculature. Because liquid cetyl myristoleate is a fatty acid ester, cellular membrane integrity or fluidity and cell-to-cell signal transmission are possible mechanisms of action.

Intake of alcohol, excess sugars, nicotine, or acidic foods may alter local pH levels, potentially influencing the 3-dimensional structure and chemical properties of liquid cetyl myristoleate. The efficacy of liquid cetyl myristoleate may have been less in patients who consumed these substances. Such alteration in structure and function may have reduced the absorption and assimilation of liquid cetyl myristoleate into the gastrointestinal tract, leading to minimal or no improvement in FM symptoms.

After starting the liquid cetyl myristoleate, all patients initially reported poorer overall health (lasting 2-5 days), followed by rapid improvement and an overall sense of enhanced well-being, which may be explained by a Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction. This theory, also known as a “healing crisis,” proposes a temporary intensification of disease symptoms (manifested by fever, chills, headache, myalgia, and other flu-like symptoms) caused by released toxins, which result in a cytokine cascade.43 The Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction has been shown to increase inflammatory cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor, interleukin 6, and interleukin 8, during periods of fever exacerbation.44,45

Our study had some limitations. The therapeutic effect of liquid cetyl myristoleate was negatively influenced by alcohol intake, corticosteroid use, consumption of high-fat meals (especially within several hours of dosing), and mixture of the drug with fruit juice or any high-carbohydrate drink. The ability of the liver to assimilate and process fatty acids may be compromised by the intake of certain substances or the use of some medications, possibly inhibiting the absorption of liquid cetyl myristoleate. Future investigators of liquid cetyl myristoleate to treat FM should evaluate a larger study sample or, if funds are available, perform a double-blind placebo-controlled trial.

View more on this study at LiquidCMO.com

David Arneson, NMD received his doctorate in naturopathic medicine in August 2000 from Southwest College of Naturopathic Medicine. Since 1988, Dr Arneson has worked in both the volunteer and employee capacity in the field of addiction, as well as with the seriously mentally ill, working extensively with both adult and adolescent populations. From October 2000 to July 2002, he served in the capacity of Clinical/Medical Director at the Naturopathic Detox Program, a non-profit 14-28 day residential naturopathic drug and alcohol detoxification facility. From February 2003 to March 2007, he held the position of Medical Director of The River Source Naturopathic Detoxification and Treatment Program (a 30-day program) in Mesa, Arizona, where he still works part time. From November 2007 to June 2009, Dr Arneson was medical director of the World Addiction and Health Institute (WAHI) in Phoenix, Arizona. He is an adjunct clinical instructor (since 2001) of naturopathic medicine at the Southwest College of Naturopathic Medicine and Health Sciences where he supervises and trains student doctors in clinical settings. He also maintains a private practice, focusing on treatment of alcoholism, drug dependency, and chronic disease.

Robert F. Waters, PhD earned his doctorate in genetics with graduate minors in biochemistry and statistics from Montana State University in 1975. Postdoctoral training and a faculty appointment were added at Kansas State University in Manhattan, Kansas. His research duties at KSU included radioactive tracing of DNA associated with intergeneric hybridization. During his tenure at Kansas State, Dr Waters had the privilege of working with the Nobel Prize Laureate Dr Norman E. Borlaug in genetics with CIMMYT near Mexico City (Toluca) and Ciudad Obregon in Sonora, Mexico. Following 20 years in private industry, Dr Waters joined the faculty at the Southwest College of Naturopathic Medicine and Health Sciences (SCNM) in 1993 as Professor of Medical Biochemistry and Medical Genetics. Dr Waters also is involved in anti-viral research at ASU/BDI in Tempe, AZ.

Robert F. Waters, PhD earned his doctorate in genetics with graduate minors in biochemistry and statistics from Montana State University in 1975. Postdoctoral training and a faculty appointment were added at Kansas State University in Manhattan, Kansas. His research duties at KSU included radioactive tracing of DNA associated with intergeneric hybridization. During his tenure at Kansas State, Dr Waters had the privilege of working with the Nobel Prize Laureate Dr Norman E. Borlaug in genetics with CIMMYT near Mexico City (Toluca) and Ciudad Obregon in Sonora, Mexico. Following 20 years in private industry, Dr Waters joined the faculty at the Southwest College of Naturopathic Medicine and Health Sciences (SCNM) in 1993 as Professor of Medical Biochemistry and Medical Genetics. Dr Waters also is involved in anti-viral research at ASU/BDI in Tempe, AZ.

Seth Black, NMD received his bachelor of science degree in biology from Arizona State University (Phoenix) and his doctorate in naturopathic medicine from Southwest College of Naturopathic Medicine (Tempe, Arizona). While at Southwest College, Dr Black assisted in teaching physiology, anatomy, and neuroanatomy. In his private practice, Dr Black focuses on autoimmune disorders, fibromyalgia, chronic disease, pain syndromes, and weight management. Dr Black has presented lectures to various fibromyalgia support groups in Phoenix, including a speaking engagement at Verde Valley Medical Center, in Cottonwood, Arizona, in December 2010.

Seth Black, NMD received his bachelor of science degree in biology from Arizona State University (Phoenix) and his doctorate in naturopathic medicine from Southwest College of Naturopathic Medicine (Tempe, Arizona). While at Southwest College, Dr Black assisted in teaching physiology, anatomy, and neuroanatomy. In his private practice, Dr Black focuses on autoimmune disorders, fibromyalgia, chronic disease, pain syndromes, and weight management. Dr Black has presented lectures to various fibromyalgia support groups in Phoenix, including a speaking engagement at Verde Valley Medical Center, in Cottonwood, Arizona, in December 2010.

Barry J Gelinas, DC, MD has 23 years of clinical experience concentrating on the assessment and management of chronic pain. In the course of Dr Gelinas’ clinical work, he founded multidisciplinary pain clinics in Edmonton, Alberta, including the Mayfield Pain Clinic and subsequently the Interdisciplinary Pain Institute (later re-named HealthPointe Medical Centers). He also developed assessment and treatment protocols for those clinics based upon evidence-based medicine and best practices at the time. Dr Gelinas has been applauded as a diagnostician and for his skill in assessing difficult personal injury and chronic pain cases. His current clinical focus is chronic non-cancer spine pain and complicated personal injury cases. He has a special interest in the use of minimally invasive interventional fluoroscopically guided procedures in the diagnosis and management of chronic non-cancer spine pain. Dr Barry Gelinas is adjunct medical research professor and senior medical research consultant for the SCNM Research Department in Tempe, Arizona. He can be reached at doctorgelinas@gmail.com.

Barry J Gelinas, DC, MD has 23 years of clinical experience concentrating on the assessment and management of chronic pain. In the course of Dr Gelinas’ clinical work, he founded multidisciplinary pain clinics in Edmonton, Alberta, including the Mayfield Pain Clinic and subsequently the Interdisciplinary Pain Institute (later re-named HealthPointe Medical Centers). He also developed assessment and treatment protocols for those clinics based upon evidence-based medicine and best practices at the time. Dr Gelinas has been applauded as a diagnostician and for his skill in assessing difficult personal injury and chronic pain cases. His current clinical focus is chronic non-cancer spine pain and complicated personal injury cases. He has a special interest in the use of minimally invasive interventional fluoroscopically guided procedures in the diagnosis and management of chronic non-cancer spine pain. Dr Barry Gelinas is adjunct medical research professor and senior medical research consultant for the SCNM Research Department in Tempe, Arizona. He can be reached at doctorgelinas@gmail.com.

Jeffrey Langland, PhD received his doctoral degree in virology from Arizona State University (Phoenix) in December 1990. His area of interest is investigating and understanding the complex cellular defenses against microorganisms. After graduating from Arizona State, he was a postdoctoral fellow at University of California–Davis, studying oncolytic viruses, then held a postdoctoral position at the University of Wyoming (Laramie), comparing similarities between plant and human defenses against viruses. In 1995, he returned to Arizona State University as a research assistant professor. In this capacity, he has taught several courses, including general virology and the biology of AIDS. Maintaining his position at Arizona State University, Dr Langland became the first joint faculty member at Southwest College of Naturopathic Medicine (Tempe, Arizona) in August 2007, where he is an instructor of medical microbiology and concepts in research courses. Dr Langland is also cochair of the research department, bringing new insight and a fresh approach to research for the students.

Jeffrey Langland, PhD received his doctoral degree in virology from Arizona State University (Phoenix) in December 1990. His area of interest is investigating and understanding the complex cellular defenses against microorganisms. After graduating from Arizona State, he was a postdoctoral fellow at University of California–Davis, studying oncolytic viruses, then held a postdoctoral position at the University of Wyoming (Laramie), comparing similarities between plant and human defenses against viruses. In 1995, he returned to Arizona State University as a research assistant professor. In this capacity, he has taught several courses, including general virology and the biology of AIDS. Maintaining his position at Arizona State University, Dr Langland became the first joint faculty member at Southwest College of Naturopathic Medicine (Tempe, Arizona) in August 2007, where he is an instructor of medical microbiology and concepts in research courses. Dr Langland is also cochair of the research department, bringing new insight and a fresh approach to research for the students.

References

1. Rasker Johannes J., Wolfe Frederick: Chaper 38 – Fibromyalgia: Firestein: Kelley’s Textbook of Rheumatology, 8th ed. (MD Consult)

2. Wolfe F: Diagnosis of fibromyalgia. J Musculoskel Med 1990; 7:53-69.

3. Yunus MB, Masi AT: Fibromyalgia, restless legs syndrome, periodic limb movement disorder, and psychogenic pain. In: McCarty DJ, Koopman WJ, ed. Arthritis and allied conditions: a textbook of rheumatology, Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1993:1383-1405.

4. Nielson WR, Grace GM, Hopkins M, et al: Concentration and memory deficits in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome. J Musculoskel Pain 1995; 3:123.

5. Bockenstedt Linda K.: Chapter 100 – Clinical Features of Lyme Disease: Firestein: Kelley’s Textbook of Rheumatology, 8th ed.

6. Staud Roland: Abnormal Pain Modulation in Patients with Spatially Distributed Chronic Pain: Fibromyalgia. Rheumatic Diseases Clinics of North America – Volume 35, Issue 2 (May 2009)

7. Lowe JC: The metabolic treatment of fibromyalgia, Boulder, CO, McDowell Publishing, 2000.

8. Moldofsky H, Scarisbrick P: Induction of neurasthenic musculoskeletal pain syndrome by selective sleep stage deprivation. Psychosom Med 1976; 38:35-44.

9. Moldofsky H, Warsh JJ: Plasma tryptophan and musculoskeletal pain in non-articular rheumatism (“fibrositis syndrome”). Pain 1978; 5:65-71.

10. Moldofsky H: Rheumatic pain modulation syndrome: The interrelationship between sleep, central nervous system serotonin, and pain. Adv Neurol 1982; 33:51-57

11. Stahl SM. Fibromyalgia: Pathways and neurotransmitters. Hum Psychopharmacology Clin Exp. 2009;24:S11–S17.

12. Cordero MD, Miguel MD, Carmona-López I, Bonal P, Campa F, Moreno-Fernández AM.: Oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction in Fibromyalgia. MINIREVIEW. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2010 Apr 29;31(2):169-173. [Epub ahead of print]

13. Cordero MD, Moreno-Fernández AM, deMiguel M, Bonal P, Campa F, Jiménez-Jiménez LM, Ruiz-Losada A, Sánchez-Domínguez B, Sánchez Alcázar JA, Salviati L, Navas P.: Coenzyme Q10 distribution in blood is altered in patients with fibromyalgia. Clin Biochem. 2009 May;42(7-8):732-5. Epub 2008 Dec 25.

14. Cordero MD, De Miguel M, Moreno Fernández AM, Carmona López IM, Garrido Maraver J, Cotán D, Gómez Izquierdo L, Bonal P, Campa F, Bullon P, Navas P, Sánchez Alcázar JA.: Mitochondrial dysfunction and mitophagy activation in blood mononuclear cells of fibromyalgia patients: implications in the pathogenesis of the disease. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12(1):R17. Epub 2010 Jan 28.

15. Katz DL, Greene L, Ali A, Faridi Z.: The pain of fibromyalgia syndrome is due to muscle hypoperfusion induced by regional vasomotor dysregulation. Med Hypotheses. 2007;69(3):517-25. Epub 2007 Mar 21.

16. Liptan GL.: Fascia: A missing link in our understanding of the pathology of fibromyalgia. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2010 Jan;14(1):3-12

17. Wolfe F, Smythe HA, Yunus MB, et al: The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of fibromyalgia: report of the multicenter criteria committee. Arthritis Rheum 1990; 33:160-172.

18. Wigers SH, Stiles TC, Vogel PA: Effects of aerobic exercise versus stress management treatment in fibromyalgia. Scand J Rheumatol 1996; 25:77-86.

19. Burckhardt CS, Mannerkorpi K, Hedenberg L, et al: A randomized, control clinical trial of education and physical training for women with fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol 1994; 21:714-720.

20. Mengshoel AM, Førre O: Physical fitness training in patients with fibromyalgia. J Musculoskel Pain 1993; 1:267-272.

21. Donaldson MS, Speight N, Loomis S: Fibromyalgia syndrome improved using a mostly raw vegetarian diet: an observational study. BMC Complement Altern Med 2001; 1:7.

22. Azad KA, Alam MN, Haq SA, et al: Vegetarian diet in the treatment of fibromyalgia. Bangladesh Med Res Counc Bull 2000; 26:41-47.

23. Franca DS, Souza AL, Almeida KR, et al: B vitamins induce an antinociceptive effect in the acetic acid and formaldehyde models of nociception in mice. Eur J Pharmacol 2001; 421:157-164.

24. Eckert M, Schejbal P: [Therapy of neuropathies with a vitamin B combination. Symptomatic treatment of painful diseases of the peripheral nervous system with a combination preparation of thiamine, pyridoxine and cyanocobalamin.]. Fortschr Med 1992; 20(110):544-548.

25. Pioro-Boisset M, Esdaile JM, Fitzcharles MA: Alternative medicine use in fibromyalgia syndrome. Arthritis Care Res 1996; 9:13-17.

26. Gamber RG, Shores JH, Russo DP, et al: Osteopathic manipulative treatment in conjunction with medication relieves pain associated with fibromyalgia syndrome: results of a randomized clinical pilot project. J Am Osteopath Assoc 2002; 102:321-325.

27. Hains G, Hains F: A combined ischemic compression and spinal manipulation in the treatment of fibromyalgia: a preliminary estimate of dose and efficacy. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2000; 23:225-230.

28. Blunt KL, Rajwani MH, Guerriero RC: The effectiveness of chiropractic management of fibromyalgia patients: a pilot study. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 1997; 20:389-399.

29. Offenbacher M, Stucki G: Physical therapy in the treatment of fibromyalgia. Scand J Rheumatol Suppl 2000; 113:78-85.

30. Leuschner J: Antinociceptive properties of thiamine, pyridoxine and cyanocobalamin following repeated oral administration to mice. Arzneimittelforschung 1992; 42:114-115.

31. Dordain G, Aumaitre O, Eschalier A, et al: Vitamin B12, an analgesic vitamin? Critical examination of the literature. Acta Neurol Belg 1984; 84:5-11.

32. Massey PB.: Reduction of fibromyalgia symptoms through intravenous nutrient therapy: results of a pilot clinical trial. Altern Ther Health Med. 2007 May-Jun;13(3):32-4.

33. Itoh K, Kitakoji H.: Effects of acupuncture to treat fibromyalgia: a preliminary randomised controlled trial. Chin Med. 2010 Mar 23;5:11.

34. Relton C, Smith C, Raw J, Walters C, Adebajo AO, Thomas KJ, Young TA.: Healthcare provided by a homeopath as an adjunct to usual care for Fibromyalgia (FMS): results of a pilot Randomised Controlled Trial. Homeopathy. 2009 Apr;98(2):77-82

35. John Buckner Winfield, MD, Herman and Louise Smith Distinguished Professor of Medicine in Arthritis Emeritus, Department of Medicine, Senior Member, Neurosensory Disorders Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; Consulting Rheumatologist, Appalachian Regional Rheumatology, Updated: Jul 14, 2009: Fibromyalgia: Treatment & Medication (MEDSCAPE)

36. Diehl HW, May EL,: Cetyl myristoleate isolated from Swiss albino mice: an apparent protective agent against adjuvant arthritis in rats. J Pharm Sci. 1994 Mar;83(3):296-9.

37. http://www.harrydiehl.com/

38. Hesslink R Jr, Armstrong D 3rd, Nagendran MV, Sreevatsan S, Barathur R.: Cetylated fatty acids improve knee function in patients with osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol. 2002 Aug;29(8):1708-12.

39. Kraemer WJ, Ratamess NA, Anderson JM, Maresh CM, Tiberio DP, Joyce ME, Messinger BN, French DN, Rubin MR, Gómez AL, Volek JS, Hesslink R Jr.: Effect of a cetylated fatty acid topical cream on functional mobility and quality of life of patients with osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol. 2004 Apr;31(4):767-74.

40. Hunter KW Jr, Gault RA, Stehouwer JS, Tam-Chang SW.: Synthesis of cetyl myristoleate and evaluation of its therapeutic efficacy in a murine model of collagen-induced arthritis. Pharmacol Res. 2003 Jan;47(1):43-7.

41. Cochran Chuck: Arthritis & Cetyl Myristoleate 1996 (21 pages) ISBN # 0-9657080-8-6

42. Siemandi H. “The effect of cis-9-cetyl myristoleate (CMO) and adjunctive therapy on arthritis and auto-immune disease: a randomized trial”. Townsend Letter for Doctors and Patients 1997; Aug/Sept:58–63.

43. Griffin GE. Cytokines involved in human septic shock–the model of the Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction: J Antimicrob Chemother. 1998 Jan;41 Suppl A:25-9.

44. Vidal V, Scragg IG, Cutler SJ, Rockett KA, Fekade D, Warrell DA, Wright DJ, Kwiatkowski D.: Variable major lipoprotein is a principal TNF-inducing factor of louse-borne relapsing fever. Nat Med. 1998 Dec;4(12):1416-20.

45. Kaplanski G, Granel B, Vaz T, Durand JM.: Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction complicating the treatment of chronic Q fever endocarditis: elevated TNFalpha and IL-6 serum levels. J Infect. 1998 Jul;37(1):83-4.