Catherine Darley, ND

Does the phrase ‘Sleeping like a baby’ bring up pictures in your mind of a baby sleeping deeply? Or does it bring images of a crying baby who’s been up every 2 hours all night? Somehow, both of these pictures come to mind for me.

Sleep problems occur in 20-30% of infants and toddlers.1 This concern is frequently brought to primary care providers. Because of the impact sleep has on an infant’s development and on parental functioning, infant sleep health merits attention in the naturopathic office.

The Development of Sleep

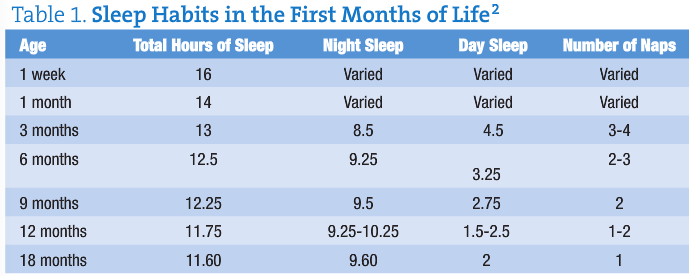

Sleep is a physiological process that begins very early, even detected in utero with quiet and active periods. In the newborn, sleep is spread over the 24-hr day. However, within a few weeks sleep begins to coalesce into the night, allowing longer wake periods. Table 1 shows how sleep changes over the first months of life.

Infant Sleep and Later Health

We know that disrupted sleep in adults and older children interferes with overall health and functioning in many ways – physical, mental, and emotional. In infants, we can see some of those same relationships.

The prevalence of overweight individuals has been increasing in America. One recent study looked at the sleep of children at age 6, 12, and 24 months.3 The researchers then assessed their BMI and subscapular and triceps skinfold thickness at 3 years of age. They concluded “daily sleep duration of less than 12 hours during infancy appears to be a risk factor for overweight and adiposity in preschool-aged children.”

In toddlers 12 to 36 months of age, those with the more disrupted sleep had the highest morning cortisol levels on waking, and were rated by teachers to have more negative emotionality and internalizing behavior.4

Mother-Infant Sleep Interactions

The interaction between the mother’s mood and child’s sleep also begins very early, before birth. It is a bi-directional interaction, in which mother’s psychological health impacts the infant’s sleep, and the infant’s sleep also impacts maternal mood. Let’s first look at how maternal psychological health impacts infant sleep.

One study included 874 women enrolled in the Southampton Women’s Survey who were followed through subsequent pregnancies.5 When their infants were 6 and 12 months of age the mothers reported how often the baby woke in the night. Those infants whose mothers were psychologically distressed before pregnancy had a 23% greater risk of waking at 6 months, and 22% greater risk at 12 months of age. This increased risk was independent of bedroom sharing, mother’s education level, and breastfeeding. Likewise, another study found that anxiety and depression during pregnancy increased infant night awakenings and decreased infant total sleep time at 2 and 8 months of age.6 Maternal separation anxiety has been shown to influence settling to sleep routines and night wakenings.7 In my office it has been noticeable that mothers with a history of unintentional pregnancy loss are most attentive to their infants during the night, and their infant is then less able to self-soothe to sleep.

Many studies have looked at how maternal mood and mental health are impacted by infant sleep patterns. The mothers of infants with sleep disturbance have increased rates of depression.8 This sleep fragmentation is more strongly associated with depression than infant temperament.9 The good news is that when the infant’s sleep disturbance is resolved, the mother’s mood is improved.10

Not as much is known about the relationship between infant sleep and the father’s experience. One study that did include fathers found that during both the last prenatal month and the first month postpartum fathers got less sleep than the mothers.11 Postpartum, fathers had less sleep than previously, and what they did get was more disturbed. Their fatigue in both the morning and evening was increased above that of late pregnancy. The level of postpartum fatigue the fathers reported was comparable to the fatigue felt by the mothers.

Behavioral Insomnia of Childhood

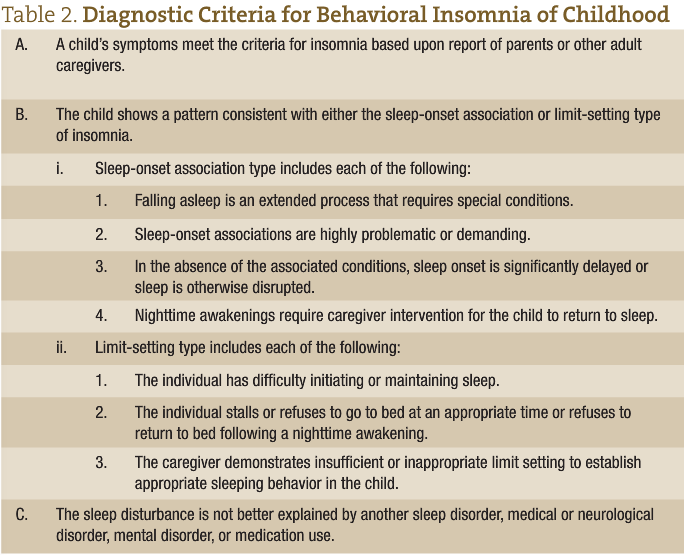

Sleeplessness can have many causes. When physiological causes have been ruled out, the infant may be experiencing Behavioral Insomnia of Childhood, which has the ICD-9 code V69.5. This disorder is discussed in The International Classification of Sleep Disorders, the diagnostic and coding manual for sleep disorders.12 There are 2 main types, with the first being limit-setting sleep disorder, and the other sleep-onset association type.

Avi Sadeh, pediatric sleep researcher, has developed the Brief Infant Sleep Questionnaire, included in Figure 1. This tool can be used clinically to evaluate your patient’s sleep. Referral to a sleep specialist is recommended if a child (age 6 to 30 months) “wakes up >3 times per night, spends >1 hour in wakefulness during the night, or spends <9 hours in sleep (day and night).”13

Behavioral Sleep Treatments

There are many techniques to help babies learn to sleep well on their own, from the ‘cry it out’ method to the ‘No-Cry Sleep Solution’ by Elizabeth Pantley.14 The American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) has written practice parameters on these methods. Unmodified extinction and parent education are generally accepted strategies with a high degree of clinical certainty, while graduated extinction has a moderate degree of certainty.15

In the unmodified extinction method (colloquially called ‘cry it out’), the child is put down in his bed at the same time each night. He then is left so that he can sleep until his scheduled wake time. The parents check on the baby only for safety, and in case of illness. Parents report that children learn to sleep through the night in a short time with this method. A difficulty is that parents need to be able to tolerate listening to their child cry. A variation is for the parent to stay in the bedroom with the child, but ignore the child and his behavior.

Gradual extinction is when there is a regular schedule of briefly checking on the baby. The amount of time between checks gradually lengthens, giving the baby time to learn to soothe himself.

In the ‘No-Cry Sleep Solution’ the baby is put to bed when drowsy but awake. The parent then gradually gives less and less soothing to the child over the course of many nights or weeks. An example of this would be the first night the parent no longer picks up the child, but will hold their hand and sing until the child sleeps. The next step (started days later) may be sitting next to the bed, singing without hand-holding. That might be followed by sitting progressively further from the bed until the parent is outside the bedroom door.

Another behavioral method is parent education and prevention of sleep problems. This can be done in prenatal classes or during the first 6 months of age. One study in Japan looked at a very brief intervention, which consisted of a sleep education booklet and 10 minutes of group education on ‘how to promote favorable sleep patterns in infants’.16 When assessing the families 3 months later, they found that the parents did fewer behaviors that interfere with the child self-soothing, and did more of the behaviors that promote healthy sleep.

Sleep-Inducing Bedtime Routines

Daytime routines in general help establish a predictable and secure environment for children, resulting in better behavior and less parental stress. Creating a bedtime routine of the same activities in the same order each night can likewise result in improved sleep. Recent research found that when a standard bedtime routine was implemented for just 2 weeks, infants (ages 7-18 months) fell asleep more quickly, woke up less often in the night, and were awake for shorter times.17 The bedtime routine used in this study consisted of a bath, a massage, then quiet cuddling, with “lights out within 30 minutes of the end of the bath.” Mother’s mood was also significantly improved.

Advising Parents

Bringing all the above information into recommendations for parents, here is a sample treatment plan.

Start with educating the parents about normal nighttime sleep and naps during the first year of life. This will give them some perspective in evaluating their own child. Include information on how sleep impacts the infant’s later health, if appropriate.

Set the sleep environment up in a way that will be consistent both throughout the night, and from night to night. Having treated many adults with sleep problems, I also recommend that parents limit the use of special tools, such as sound machines, night lights, pacifiers, etc, as the child may have difficulty with sleep when traveling to places that don’t have those tools. This recommendation ties in with Diagnostic Criteria B.i.2 “sleep-onset associations are highly problematic or demanding” (see Table 2).

Establish a short (<30 minute) bedtime routine that is done in the same order each night. If books are read or a song sung, it should be the exact same each night.

Decide with the parents which of the above behavioral sleep treatments fits with their overall parenting philosophy and style. Then write out the plan and post it. I find that posting it helps parents when it is the middle of the night and they are tired, yet need to help their child go back to sleep.

Advise parents that being consistent with their approach is a very important piece of this process. Determine if the parent is well rested enough to implement the sleep plan, and address parent sleepiness if need be.

Because of the impact infants’ sleep health has on long-term health and parental well-being, guiding the family to create positive sleep habits will have a strong impact on the overall health of the family. ‘Sleeping Like a Baby’ will then be a positive experience for everyone in the household.

Catherine Darley, ND practices at The Institute of Naturopathic Sleep Medicine in Seattle, Washington. Dr. Darley is passionate about the role healthy sleep plays in overall health and quality of life, and is pioneering the field of naturopathic sleep medicine. While attending Bastyr, Dr. Darley did shift work many nights at Seattle area sleep labs, so this topic is close to her heart. In addition to providing patient care, she does public sleep education and corporate consultations.

Catherine Darley, ND practices at The Institute of Naturopathic Sleep Medicine in Seattle, Washington. Dr. Darley is passionate about the role healthy sleep plays in overall health and quality of life, and is pioneering the field of naturopathic sleep medicine. While attending Bastyr, Dr. Darley did shift work many nights at Seattle area sleep labs, so this topic is close to her heart. In addition to providing patient care, she does public sleep education and corporate consultations.

References

1. Mindell JA, Kuhn B, Lewin DS, Meltzer LJ, Sadeh A; American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Behavioral treatment of bedtime problems and night wakings in infants and young children. Sleep. 2006;29(10):1263-1276.

2. Ferber R. Solve Your Child’s Sleep Problems. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster; 1985:11.

3. Taveras EM, Rifas-Shiman SL, Oken E, Gunderson EP, Gillman MW. Short sleep duration in infancy and risk of childhood overweight. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162(4):305-311.

4. Scher A, Hall WA, Zaidman-Zait A, Weinberg J. Sleep quality, cortisol levels, and behavioral regulation in toddlers. Dev Psychobiol. 2010;52(1):44-53.

5. Baird J, Hill CM, Kendrick T, Inskip HM; SWS Study Group. Infant sleep disturbance is associated with preconceptional psychological distress: findings from the Southampton Women’s Survey. Sleep. 2009;32(4):566-568.

6. O’Connor TG, Caprariello P, Blackmore ER, Gregory AM, Glover V, Fleming P; ALSPAC Study Team. Prenatal mood disturbance predicts sleep problems in infancy and toddlerhood. Early Hum Dev. 2007;83(7):451-458.

7. Scher A. Maternal separation anxiety as a regulator of infants’ sleep. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008;49(6):618-625.

8. Hiscock H, Wake M. Infant sleep problems and postnatal depression: a community-based study. Pediatrics. 2001;107(6):1317-1322.

9. Goyal D, Gay C, Lee K. Fragmented maternal sleep is more strongly correlated with depressive symptoms than infant temperament at three months postpartum. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2009;12(4):229-237.

10. Hiscock H, Bayer J, Gold L, Hampton A, Ukoumunne OC, Wake M. Improving infant sleep and maternal mental health: a cluster randomized trial. Arch Dis Child. 2007;92(11):952-958.

11. Gay CL, Lee KA, Lee SY. Sleep patterns and fatigue in new mothers and fathers. Biol Res Nurs. 2004;5(4):311-318.

12. American Academy of Sleep Medicine. The International Classification of Sleep Disorders: Diagnostic and Coding Manual. 2nd ed. Westchester, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2005:23.

13. Sadeh A. A brief screening questionnaire for infant sleep problems: validation and findings for an internet sample. Pediatrics. 2004;113(6):e570-e577.

14. Pantley E. The No-Cry Sleep Solution: Gentle Ways to Help Your Baby Sleep Through the Night. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2002.

15. Morgenthaler TI, Owens J, Alessi C, et al; American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Practice parameters for behavioral treatment of bedtime problems and night wakings in infants and young children. Sleep. 2006;29(10):1277-1281.

16. Adachi Y, Sato C, Nishino N, Ohryoji F, Hayama J, Yamagami T. A brief parental education for shaping sleep habits in 4-month-old infants. Clin Med Res. 2009;7(3):85-92.

17. Mindell JA, Telofski LS, Wiegand B, Kurtz ES. A nightly bedtime routine: impact on sleep in young children and maternal mood. Sleep. 2009;32(5):599-606.