FRASER SMITH, MATD, ND

The old saw that “doctors are terrible business people” has some truth to it.1 The tremendous focus required to achieve proficiency in biomedical sciences, diagnosis, and therapeutics comes at a price. That singular focus can preclude learning other important skills. Wrapping all of those skills together and then effectively delivering naturopathic care to a patient is another great evolutionary step for a naturopathic medicine student – one that can be all consuming at times. Business skills are important and would seem to belong in the curriculum, but educators find that it is hard to make classroom-based business training stick. Yet, a few days with a seasoned practitioner can fire up the enthusiasm of a student, as well as give them real insight into how they want to set up their practice. So, are the skills of business and practice management “caught” (in an actual situation) or “taught” (in a classroom)?

To ignore the exigencies of the business side of things has never been a luxury that naturopathic physicians can afford. Positioning one’s services in a way that draws both attention and patients, and delivering them in a way that leaves some net income for the doctor after all the bills are paid, is a necessity. New naturopathic medicine graduates may feel, justifiably, that they have an incredible gift to share with their future patients; however, they won’t sustain themselves, let alone their practice, in the world if they are not properly set up to do so.

I have heard the criticism of the profession over the years that it has a “poverty mentality.” There are so many examples of ethically run successfully naturopathic practices, though, that this phrase could rightfully be retired. The lesson it carries, especially for students, is this: “It is not avarice to want to make a living, and it is not wise to give away your services for less than what they are worth.” One response I have given to interns who felt shy about asking a patient to pay for a botanical tincture that would need to be replaced weekly for a period of time is this: “When was the last time your dentist apologized for ordering X-rays?” It’s one thing to explain the cost of a test or service without sales pressure and to give a patient a moment to weigh the feasibility for themselves. But it’s another to presume to be their banker and hold back on making the best recommendations you can. I attended a clinic in an economically depressed neighborhood for several years, where I did have to make treatment plans grounded in reality; some of these patients really could not afford what my patients in midtown Toronto often could. But, as a general rule, if dentists, chiropractors, podiatrists, medical and osteopathic doctors, and more make recommendations and set a service fee based on the market and their own needs, naturopathic doctors ought to do likewise.

The Value of Business in Naturopathic Curricula

Even though it must compete with a gigaton of other activities, the business or “practice management” aspect of the profession requires some core curriculum. The CNME-accredited naturopathic colleges in North America all teach some of this material. It is the right thing to do to prepare our students as best we can for future success, and the programs work hard at it. The delivery can vary, and it should, given that all programs have unique and creative ways of delivering the program. Small, modular exercises in micro-skills of business, which build up to a capstone project, are one way. Logically structured and self-contained courses such as “marketing” or “writing a business plan” are another. It is perpetually challenging to ensure that the courses are enough. Just as undergraduate courses never sufficiently prepare a student for the shock of having 26 credits of basic sciences as a 1st-year student in naturopathic college, the best business curriculum can never forestall the stark reality and earnestness of post-academic life. So, with those limitations in mind, what are the arguments for learning business in the school of hard knocks versus in a classroom?

The Case for “Caught”

Many skills that we associate with the general heading of business are best learned experientially. The acquisition of these skills may not be passive, but they come about by being immersed in experience. Looking at a balance sheet and finding that your funds went to rent and supplies and salaries far faster than you ever imagined is a great doorway to learning about cost allocation. Providing services on the cheap and finding that patients don’t value them is a superb way to find out that people tend to take more seriously what they pay for. Some skills in life just require experience. Just the simple act of talking to and motivating patients has a passage point from theory to actually doing it. Likewise, dealing with vendors, banks, counties and states/provinces, lessors, etc, advances a certain savvy (a word derived from the Latin sapere, meaning “to be wise”). Experience also teaches us that regardless of education level, people are pretty good at seeing through humbug, and tend to appreciate doctors who treat them well, treat them fairly, and do what they say they are going to do. The “town” versus “gown” distinction, or experience in the real world versus book learning, certainly holds sway on that point of gaining wisdom.

The Case for “Taught”

The whole point of professional training is to provide preparation for a career. There is a standard for what an entry-level naturopathic physician should be, including having enough knowledge and judgment to be safe. That’s what licensing examinations such as the NPLEX are for. But there is also a need for some background knowledge before leaving school. Understanding the structure of a business plan as a bank would expect to see it has value. Knowing the ends of a balance sheet, and how to read a practice agreement or lease agreement, is good education. Even though these skills are somewhat in hibernation until one has to really call upon them, they still have value. Knowing the theoretical basis of things, and where to find information about them or whom to seek guidance from, are part of an education. So, while a classroom or online course instruction does not make a student particularly smart or successful in running a practice, they can give that student an awesome head start.

Teach a Doc to Fish

There is a time-tested way to promote a more rapid transmission of business knowledge and produce a more confident graduate. It involves spending time around practitioners in the field. A 4th-year naturopathic medical student can learn a broad array of tools at the right practice. The way that the front desk and reception area greet and process patients is one example. The supplies and supplements that the practice sells to patients is another. The doctor will have a certain way of spending time and speaking with their patients. There is the use of staff and the physical attributes of the practice, including its location. These all come together into an experience. An intern spending a few days in a practice – or longer, in the case of a clerkship or rotation – has time to ask questions and hear stories from that doctor about what he or she learned along the way.

Perhaps an intern in the field will see some practices having difficulties. That is a learning experience, too, because they might discover why. There is often a fear among faculty that students will pick up bad habits at some practices. There is some justification for that concern: not everyone is as diligent in charting as they ought to be at all times, and every profession unfortunately has members that fall below an ethical standard at some point, and so on. But if we have properly prepared students by giving them a solid foundation in naturopathic medicine and helping them to develop skills of critical thinking, we ought not be overly protective. Moreover, the schools have some control over whom the students will observe with, as well as a lot of control over which doctors are accepted as adjunct faculty who can host interns for extended periods of time.

The colleges themselves have what are the profession’s largest medical centers, and interns learn a lot there. A clinical shift centered around a faculty member is a practice; thus, there is something condescending and a touch unethical about saying that a teaching clinic is not the “real world.” Are those patients less important than patients in smaller, private practices? But the nugget of truth in the “town versus gown” dichotomy is that the purposes of organizational structure of a large teaching clinic differ from those of a smaller private practice. Teaching clinics are a major component in a credentialing system. They impart the fundamentals of the discipline and evaluate students’ performance, give them feedback, and eventually promote them. A lot of good naturopathic medicine is practiced along the way, but the business structure and the personnel structure is that of a mid-size business, not a small business.

Business Skills in an Era of Group Practices

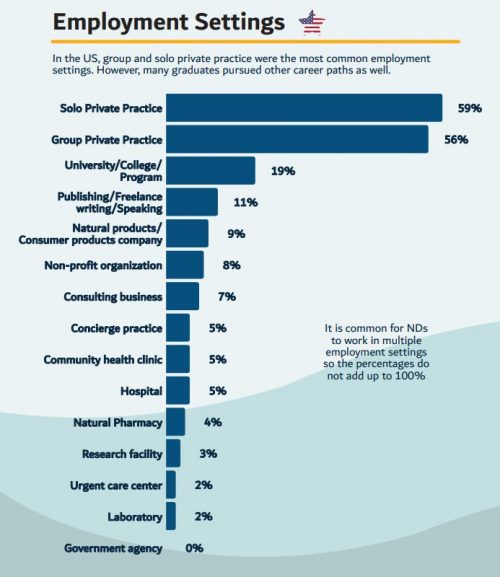

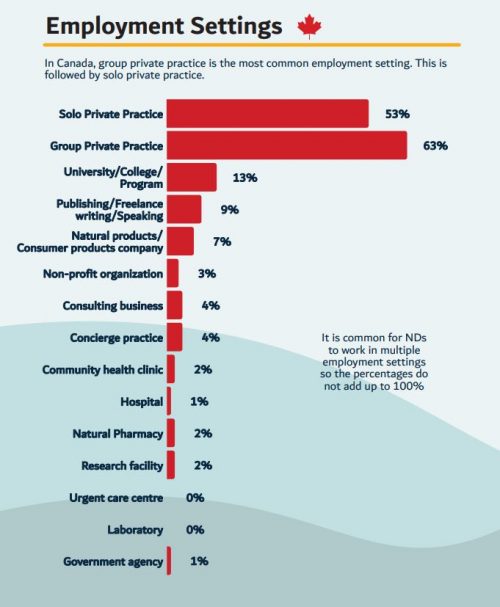

While private or small groups (2 or 3 doctors) are still fundamentally the core of naturopathic practice, they are no longer the rule. The excellent 2020 AANMC Graduate Success and Compensation Survey, conducted in the United States and Canada, found that solo practice is not the only option.2 Results from the US survey showed that 59% of graduates had a solo practice, while 56% were part of a group practice (naturopathic doctors were practicing at multiple locations in many cases; hence the percentage totals were >100) (Figure 1). A large percentage of graduates do some practice or work within an educational institution, and not always a naturopathic program. While in the single digits, there were doctors working in hospitals and in research, as well as in the publishing and natural products industry, to name a few. The Canadian results showed a similar spread of varied vocational roads, with slightly more graduates (63%) engaged in group practice than in solo practice (53%) (Figure 2).

Allopathic medicine has followed a different, if parallel, trend away from its historical roots of a doctor “hanging out a shingle.” In 2019, the number of allopathic physicians who were employed by an organization outnumbered those who were independent (although the independent category can be independent groups of associates).3

Why would graduates who plan to join a larger group or health system, or work for a business or the government, or simply join a long-standing practice really need business training? Aside from that on-the-job learning that is so valuable, the business training prepares them to be contributing members of that organization. Understanding the financial report and business goals of a larger practice can help a graduate become a working part of it, and have insight into the operations, which can lead to more contributions and, perhaps, full partnership. Knowing the way that businesses operate can help a graduate who is part of a very large organization, such as a hospital, understand that the seeming obsession with the budget is not some sort of ritual cult-like exercise, but rather is essential to the survival of the organization and the employment of the many people who work there and, ultimately, the fulfillment of its mission. Some of us may be born scientists, philosophers, and healers and not so interested in the commercial world. But like it or not, much of life is business, and too much naiveté about that has been to the detriment of many a physician. To paraphrase a quote attributed to the classical Greek (Athenian) politician, Pericles, “Just because you don’t take an interest in business doesn’t mean it won’t take an interest in you.”4

Time in the Field

Learning in context with an expert is the express lane to business acumen. Adequate preparation allows interns and entry-level naturopathic physicians to capitalize on those experiences more effectively. While there will never be enough time to teach students all of the richness of practice management, creative and time-efficient methods can help. One simple measure is to grant interns more time in the field, under appropriate supervision, to see how different doctors conduct their practice. Expanded opportunities to see the myriad ways that naturopathic physicians use their education in a surprising number of industries is another. We owe it to our students, who are the future of this profession.

References:

- Perry J, Mobley F, Brubaker M. Most Doctors Have Little or No Management Training, and That’s a Problem. December 15, 2017. Harvard Business Review. Available at: https://hbr.org/2017/12/most-doctors-have-little-or-no-management-training-and-thats-a-problem. Accessed October 16, 2020.

- Association of Accredited Naturopathic Medical Colleges. 2020 Graduate Success and Compensation Study. AANMC Web site. https://mk0aanmc2iy600cqre.kinstacdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/2020-Graduate-Success-and-Compensation-Study.pdf. Accessed October 16, 2020.

- Mazzolini C. Employed physicians outnumber independent physicians for the first time ever. May 8, 2019. Medical Economics. Available at: https://www.medicaleconomics.com/view/employed-physicians-outnumber-independent-physicians-first-time-ever. Accessed October 16, 2020.

- The Famous People. 11 Thought-Provoking Quotes & Sayings by Pericles. Available at: https://quotes.thefamouspeople.com/pericles-2547.php. Accessed October 16, 2020.

Fraser Smith, MATD, ND is Assistant Dean of Naturopathic Medicine and Professor at the National University of Health Sciences (NUHS) in Lombard, IL. Prior to working at NUHS, he served as Dean of Naturopathic Medicine at the Canadian College of Naturopathic Medicine (CCNM) in Toronto, Ontario. Dr Smith is a licensed naturopathic physician and graduate of CCNM.