David Schleich, PhD

This opening to the life we have refused again and again, until now.

(David Whyte)

At various times over the last few decades, lots of things have been touted as valuable, albeit disruptive, innovations in health care, eg, ultrasound in a doctor’s office to ultrasound on the iPhone; “fitbits” on the wrist, measuring everything from blood pressure to the number of steps walked in a day; watches with ECGs; a urine test for Alzheimer’s disease; and right up to Watson and the Jeopardy program. Disruptors everywhere. What’s a naturopathic doctor to do? What’s a naturopathic medical educator to do? The doctor will see you now, linked everywhere.

Let’s focus on 1 not-so-recent disruptor, but one that has been extrapolated widely enough to affect the very nature of the naturopathic doctor-patient relationship, interrupting the power of the precious long visit. That disruptor is EMR (electronic medical records) and its macro-version partner, EHR (electronic health records). As with all useful, new ways to populate and enhance the skills and content of naturopathic education, effective rollout and use of EMR/EHR can have unexpected side effects. The concern voiced in a recent survey of naturopathic clinical teachers is that this brave new tool will thin our doctors’ traditional patient-focused skills. Notwithstanding all our best efforts to welcome such new tools into the naturopathic repertoire, the expanding practice of generating, sustaining, and refining electronic health records and replacing traditional charting has not made things better. As with many such shifts emerging from the digital era, our naturopathic patient-care reputation may well be prone to something unexpected.

That worry among educational planners and among clinical supervisors was described by one of my interviewees as “signal to noise” ratio. Not only was he commenting on how its implementation in their multi-discipline clinic had been expensive to introduce and increasingly costly to sustain, he contended that it can mess up what the naturopathic doctor (or intern, or resident) really “intuits” and “observes” and “documents.” For those educational leaders huddled to debate how to keep the student and – as a product of our educational product – patient care, always in clear focus, such disruptors are a challenge. Is a flip-phone enough, or do I really have to migrate up-market to an iPhone or a Blackberry?

Drucker’s Metaphor

Let’s drill down into the “signal to noise” metaphor. It is a concept widely popularized by Drucker to get a handle on why it can be concerning as it relates to electronic documentation, or, more precisely, to the process which creates that documentation. Drucker’s notion of “signal to noise,” other naturopathic educators are likely to concur, is incisive in separating out the elements of the disruptive nature of EHR/EMR, notwithstanding their remarkable utility and value. In any case, in the formula below, “P” is average power, “signal” is meaningful information, “noise” is background, unwanted signal/information, and “R” is ratio.

SNR = μ/σ, where μ is Mean, σ is Standard Deviation, SNR is Signal-to-Noise Ratio.

P signal

SNR = _____

P noise

Peter Drucker’s well-known “signal-to-noise ratio analogy,” as expressed in various places by this formula, is handy in explaining why the energy involved in trying to connect really good teaching with really good doctoring can be derailed or shifted in some way, away from the guiding principles of the medicine – so essential to sustaining its core – that differentiates it from the biomedicine mainstream. The worry is that even our naturopathic doctors, in their clinical training and later in their own practices, spend increasingly large amounts of time with their eyes glued to computer screens instead of looking at their patients while they talk to them (“signal to noise” in play).

To flesh out the metaphor a bit more, Drucker explains that the addition of each relay in an electric circuit halves the amount of signal that passes through it, doubling the noise. Our perspective on the design and delivery of teaching and learning, and on the precious time involved in effective patient care, is that our students and our doctors can easily get saturated with relays and more relays, circuits and more circuits, as we embrace new approaches, new techniques, and the inevitable new equipment which goes along with it all. The “static” which threatens good teaching and learning, as well as good patient care (communication), can sometimes be more about the sheer intellectual and emotional costs of joining and managing the disruptions coming our way than about the packed patient schedule on any given day and the importance of relational medicine.

The safety and creativity of our efforts, whether in the individual programs of our colleges and universities or in the more broadly-based work of our accrediting bodies (both the specialty accreditor [CNME] or our regional and state accreditors), need an operating terrain on which we can create an environment where we don’t lose the sacred ground of patient relationship.

Teaching Great Ground Rules in Patient Care

Max DePree’s ideas about “ground rules in the doing of anything worthwhile and enduring” (DePree, 1989) can guide us in teaching and reinforcing traditional strength in close patient-care, no matter what equipment we are using during the interactions. DePree says that if we need to catch all these digital fastballs in higher education and medical practice [new ideas, new concepts, new paradigms], we need good mitts, or the slam of the ball will hurt us where we learn and where we contribute to the healing process in our patients. The “mitt” for us is the collective curiosity and generosity of our deans and chairs, as well as their commitment, by and large, to sustaining traditional principles and practices.

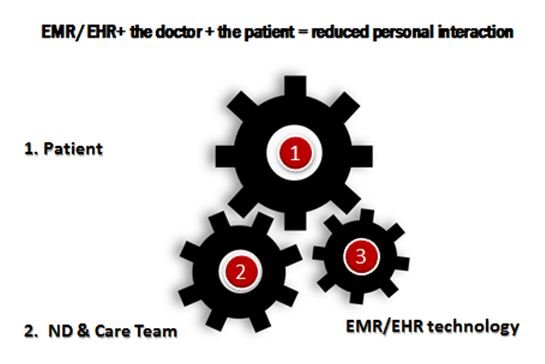

That courage and determination of our teachers to generate and sustain excellence in teaching in the noble work of professional formation can be interpreted as Luddite-like by those caught up in the fuss, rattle, urgency, and noise of post-ACA patient care. The “formed” profession of our era will want to sense the danger of being co-opted by 3rd-party insurers, for example, eager to link everyone on the payroll together to affect efficiencies, nonetheless influencing positively and negatively how and what we do. The “formed” profession, our teachers remind us, does not want to exchange doctor-patient personal contact for some formulaic EHR-prepped minutes per patient / X patient volume / X days of operation report, for example, if the “noise” of using the tool interferes with the very content and purpose of the naturopathic interaction in the first place (Figure 1).

With regard to the increasing pervasiveness of EHR and EMR systems, what we are all collectively trying to do is to keep the signal strong and the noise level down. The noise is the time taken not focused on patients, not experiencing their unique selves, not building connection. The patient suffers. The doctor suffers. And before that, our students suffer when they discover not only the abundant biomedicine content of naturopathic education these days, but also departures from a traditional practice culture. Strong assertions, I realize. Alright, there must be a study corroborating these worries. Northwestern University to the rescue…

How Much is Too Much Time On Screen?

The Northwestern University study is entitled, “Do Doctors Spend Too Much Time Looking at [the treatment room] Computer Screen?” In this piece, Spain (2014) points out, data in hand, that MDs and DOs have installed, right in the treatment room, keyboards and small desks between themselves and patients. The same study notes that when the devices necessary for the electronic charting are avoided until after the patient-doctor connection, satisfaction levels rise for both parties. When the provider is committed to getting the narrative detail down on a screen, his or her eyes (and specific attention on the individual) fall on the patient significantly less. When the provider is co-opted by this technology, which had the potential to make electronic records available for instant sharing as needed, the cost of the equipment, the software and the maintenance, coupled with the time not spent in relational communication with the patient, thins the relationship. This means there is a lot of noise in what was once a more tranquil, personal interaction. EMR and EHR systems have proven to be somewhat unsuccessful so far because of the cost and because of the harm done to the patient-doctor personal interaction. This may be less an issue with allopathic professionals, but it is clearly a growing concern among naturopathic educators.

The naturopathic doctor is not inept to have chosen such new technology for her clinic; rather, she knows that a medical home and coordinated care require efficient communication among the players. However, the doctor can be caught up inadvertently “in a legacy business model than can only prioritize sustaining innovations” rather than improve clinical effectiveness (Wanamaker, 2013). If the goal of EHRs was to enhance clinical quality, they turn out to be an expensive innovation which is hard to sustain (naturopathic medical educators shudder in the face of exponentially increasing user fees, for example). To be sure, the disappearance of rooms crammed with paper records in vertical files, replaced as they have been by sophisticated electronic systems, can be experienced as progressive, modern, clean. Instead, some say, sustaining the innovation adds operating cost without necessarily augmenting patient care.

Connecting the Dots of Disruption

What is missing in this noisy equation is an equally disruptive business model accompanying the disruptive EMR/EHR device. The 1 disruptor (on site but linked all over the block) can, when part of a concomitantly disrupting new business model, make all the dots come together. Like interconnecting gears, the technology can link the patient more effectively to his or her coordinated care-team. However, it is in the very process of using the tool that the greatest threat to the naturopathic doctor-patient relationship arises. As Wanamaker (2013) points out, the value proposition of the new technology (potentially disruptive) gets co-opted by its use being adapted to “already existing processes” in order to keep the cost-benefit overlay in balance. Building on this idea, Wanamaker (2013) goes on to recommend that, in terms of EMR/EHR use, their designers should create systems based on the doctor’s “job to be done” (aka, patient-centered), and to think beyond merely replacing old record systems (that is, adding to the continuum other patient services such as check-in, insurance processing, lab and medicinary sales, peer-to-peer chart review; aka, paying close attention to the patient’s needs more than the provider’s record-keeping-sharing goals).

It’s not just that old paper-charting is simpler, handy, logical, and fits into the pattern of the doctor’s relational interaction with the patient. The technology can be more positively disruptive in nature were it never to be utilized at the expense of the doctor-patient, in the treatment room, in the consulting room, in the enduring relationship. Then what can evolve, making the best use of this technology, is a snappier communication process among caregivers in the care team, right now and long into the future, as medical homes and multi-discipline providers work more closely together. Our teachers in our naturopathic programs all over North America are up to the challenge. Trust me.

David J. Schleich, PhD, is president and CEO of the National University of Natural Medicine (NUNM), former president of Truestar Health, and former CEO and president of CCNM, where he served from 1996 to 2003. Previous posts have included appointments as vice president academic of Niagara College, and administrative and teaching positions at St. Lawrence College, Swinburne University (Australia) and the University of Alberta. His academic credentials have been earned from the University of Western Ontario (BA), the University of Alberta (MA), Queen’s University (BEd), and the University of Toronto (PhD).

David J. Schleich, PhD, is president and CEO of the National University of Natural Medicine (NUNM), former president of Truestar Health, and former CEO and president of CCNM, where he served from 1996 to 2003. Previous posts have included appointments as vice president academic of Niagara College, and administrative and teaching positions at St. Lawrence College, Swinburne University (Australia) and the University of Alberta. His academic credentials have been earned from the University of Western Ontario (BA), the University of Alberta (MA), Queen’s University (BEd), and the University of Toronto (PhD).

References

Dardik, I. & Waitley, D. (1984). Breakthrough to Excellence: Quantum Fitness. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

Schon, D. (1987). Educating the Reflective Practitioner: Toward a New Design for Teaching and Learning in the Professions. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Senge, P. M. (1990). The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization. New York, NY: Doubleday Publishing.

Spain, E. (2014). Do Doctors Spend Too Much Time Looking at Computer Screen? January 23, 2014. Northwestern University Web site. http://tinyurl.com/zsjq54p. Accessed March 16, 2016.

Wanamaker, B. & Bean, D. (2013). Why EHRS are not (yet) disruptive. August 8, 2013. Clayton Christensen Institute Web site. http://www.christenseninstitute.org/why-ehrs-are-not-yet-disruptive. Accessed March 16, 2016.