Christina Bjorndal, ND

For many, eating disorders start subtly, such as hearing a peer make a side comment about the person’s weight, or observing a parent struggle with body image. Whatever it is, it doesn’t take long before a person can become completely lost in it.

It is from both a personal and professional viewpoint that I write this article. In my mid-30s, I made a career change to become a naturopathic doctor because I was sick and tired of being tired and sick, and I wanted to help people recover from some of the health challenges I had faced using naturopathy. Previously, I worked in business, reporting to a CEO, and had been diagnosed with several health challenges: depression (including several suicide attempts), anxiety, panic attacks, cancer (malignant melanoma), and high blood pressure. At the root of many of those health challenges laid a secret – bulimia.

Identifying the Root Cause

As with most addictive behaviors, the first step to recovery is admitting that you have a problem and are ready for help. But this admission does not come without its share of bumps along the road to recovery. There is often defeat, despair, setbacks, and falls off the wagon; however, the overall trajectory in recovery is moving forward. As naturopathic doctors, we are always striving to figure out what the root cause of “dis-ease” is, with the idea that if we can determine that, then we can fix the problem. The challenge is that the problem is often multi-factorial and therefore requires a solution that is multifaceted. In many cases, we need to look as far back as in-utero to ascertain the health of the gut biome and how this starts, or, more importantly, how it may not start if we are born via C-section. The importance of high-quality case-taking has been emphasized in previous articles in this magazine, and I want to reiterate the importance of that.

Eating disorders such as bulimia can start “innocently,” as mine did, and then serve a greater function in a person’s life, thereby becoming a symptom of a bigger problem. Most eating disorders start at the time of puberty, and it is important to ask about the use of medications such as oral contraceptives and antibiotics for acne treatment, the latter of which may affect weight.1 Also, most eating disorders are a co-morbid condition2; thus, it is always important to the identify root condition, eg, depression, anxiety, stress, lack of self-worth, hormone imbalances, etc. I would argue that in many cases, bulimia is a branch. We don’t want to chase branches in treatment; we want to address the roots.

Treatment Objectives & Steps

There are 3 “macro” systems in the body that should be assessed when treating bulimia: neurotransmitters, the neuroendocrine system, and the organs of detoxification. It is my experience that most patients have underlying imbalances in all 3 areas. The primary neurotransmitters implicated in eating disorders include serotonin, GABA, dopamine, norepinephrine, epinephrine, and glutamate.3 In terms of hormones, cortisol, progesterone, estrogen, and thyroid hormones should be evaluated. This is because hormone imbalances, in my opinion, can be a root cause of food cravings and disordered eating.

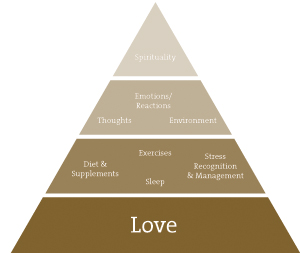

In my practice, I teach patients about the “pillars of health”: diet, sleep, exercise, stress recognition/management, thought processes, emotions/reactions, environment, spirituality and self-love (Figure 1). I always offer them faith and hope that they will get well. I affirm that they will, as by the time patients get to me, the medical system has often offered them anything but hope.

Figure 1. Pillars of Health

- Diet: Everything that goes into the body informs the body. Important goals in the treatment of eating disorders include stabilizing blood sugar levels, eating a nutrient-rich, sugar-free diet, and restoring gastrointestinal health. I do not recommend evaluation and treatment of food sensitivities, since individuals with eating disorders are already too focused on food; testing or elimination diets may thus further contribute to the mental/emotional problem rather than correct it. I find it more effective to increase the patient’s intake of healthy foods (vs remove foods) and to focus on foods that will best resolve nutritional deficiencies in the body. The key nutrients that I include are: essential amino acids (especially tryptophan3), essential fatty acids, minerals (typically zinc citrate,3 magnesium bisglycinate, calcium), and all B vitamins (with an emphasis on methylation pathways in the body). I also provide additional support for anxiety and depression using adaptogen botanical formulations. Digestive issues are common in bulimia, such as constipation, heartburn, gas, and bloating, as well as electrolyte imbalances and dental concerns.4 The prevalence of IBS is also more common in bulimics,5 and gut microflora may be imbalanced.6 Therefore, probiotic reinoculation is key. Other long-term health problems can result from bulimia, including chronic headaches, osteoporosis and menstrual cycle irregularities, such as amenorrhea, dysmenorrhea, irregular periods, and fertility concerns.7

- Sleep: Sleep is critical to mind and body repair, recovery, and restoration. Most of my bulimic patients are getting suboptimal sleep. It is imperative that this area is properly assessed and supported as needed.

- Exercise: For most, exercise is considered a good thing. The challenge with bulimia is that exercise may be used as a compensatory mechanism to control binges, especially after cessation of purging. If I suggest any exercise at all in the initial stages of treatment, it is gentle, yin-type exercise, such as yoga, tai chi, qi gong, and walking.

- Stress management and awareness of thought processes: In my practice, this is the crux of my work with patients. For many bulimic individuals, stress is what underlies their emotional, binge, and unconscious eating. I utilize aspects of 4 forms of therapy: mindfulness, compassion-focused therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, and gestalt psychotherapy. I teach patients how to recognize the “emotional wave” as it starts to rise within their physical body, and help them to strengthen their ability to refrain from acting on their emotions by relaxing into their breath. A critical part of working with patients is teaching them to observe their minds and uncover unhelpful core beliefs/thoughts. Most of us are unconsciously driven by our subconscious minds; by reprogramming faulty beliefs, we can change our lives.

- Emotions/reactions: In my own recovery, dealing with past “hurts” has been a huge component of my healing journey. At 20 years of age, I was diagnosed with a major mental health condition. I deeply felt the stigma and shame of the label, and consequently felt ostracized. The counseling techniques mentioned above are utilized to help patients understand their emotions and how they behave and react in the world – and most importantly how they can change these behaviors.

- Environment: This is addressed from 2 perspectives. Firstly, the environment we grow up in creates a profound psychological imprint. This is addressed not to blame, but to understand how we may be “programmed” and to uncover core beliefs that may not be serving us. With awareness of faulty beliefs, we can change future behaviors. Ultimately, all we can do about the past is to change our relationship with it in the present moment. The second aspect of environment is the quality of the air, food, and water we consume. For many, it is helpful to measure and address heavy metals and other environmental toxins.

- Spiritual: The spirit in you is your life form. It is my personal belief that a connection to spirit, whatever your chosen practice is, is critical and vital to healing yourself and the current state of the planet.

- Love for self: I ask all patients to rate their love for themselves on a scale of 1 to 10, with 10 being the highest. Thus far in practice, nobody has rated herself a 10/10. I feel this is the most important area to assess and address with patients, and why I have shown it as a foundational building block in my diagram (Figure 1). Patients have to value their own worth in order to make the changes that are necessary to recover from bulimia. Patients need to learn to love themselves and let that be a key force in guiding their recovery.

By no means is the above meant to be an exhaustive list. There are many other helpful resources:

- An inpatient treatment center may be required, depending on the severity of the case. Refer accordingly.

- Therapy, especially gestalt psychotherapy or cognitive-behavioral therapy.8,9 The workbook I use in clinical practice is Mind over Mood, by Christine Padesky.10 Another helpful workbook is The Brain Over Binge Workbook, by Kathryn Hansen.11

- Additional useful authors include Geneen Roth, Dr Christiane Northrup, Jennie Schaeffer

- 12-step groups, such as Overeaters Anonymous

Recovery & Suggestions for Family Members

Recovery is a continuum that often looks like this along the way: patients stop purging, but still binge. To compensate for binge activity, patients may start to over-exercise. Eventually, when they recognize this, they will stop binging and develop a healthy relationship to exercise. It may take an injury or life event, (eg, divorce) to force them to truly wake up. Be careful that a suggestion to eat healthfully is not taken to the extreme where a patient develops orthorexia nervosa – a fixation or obsession about healthy eating.12

Often individuals with eating disorders are reluctant to seek out treatment. Many times it will be a family member that calls your office for advice. Remember that each case is unique. My recommendations for family members include the following:

- Understand that your loved one may resist help. Do not take this personally and continue to try to get them help. Recognize that many people with eating disorders refuse to accept the diagnosis (yet still have to live with the symptoms).

- If you suspect your family member has an undiagnosed problem, attend a support group meeting in your area or talk to a professional about your loved one. The next step would be to ask him or her to go for an assessment. Be persistent if you encounter resistance. It is scary at first for someone to acknowledge the existence of a problem, and it is equally rewarding to accept help.

- Recognize that you cannot control your loved one. Sometimes you need to give more, and sometimes you need to give less, depending on how the person is managing his or her illness. Remember to be kind to yourself and refuel yourself on a daily basis (eg, yoga, going for a walk, preparing a healthy meal for yourself, having a warm bath, getting a massage). Ultimately, you are a guide on the journey for your loved one; however, it is that person’s life to live.

Words of Encouragement for the Patient

A person’s acknowledgement of an eating disorder is a huge step, but only the first. Changing behaviors and establishing healthy habits is a gradual process that usually includes both progress and set-backs. Gentle and regular encouragement can make a big difference in a patient’s ability to resolve an eating disorder. Here are some of the messages I find helpful to convey to my patients:

- The first step on a new path is always the hardest to take. Make it a small one, and you will be surprised that in time you will be running down the road of recovery.

- Remember that there may be potholes along the road and it may feel like the journey is long and slow at times. Trust in the healing process, be patient, and you will get “there.” There is no quick-fix solution to multi-factorial conditions.

- Everyone needs to find their own balance point – in their weight, with stress, and in life. Avoid comparing yourself to others. Trust in your own intuitive self and the inherent healing powers you have at your fingertips, while at the same time working with experienced healthcare professionals.

- Most humans have addictions, issues, and things to get over, learn or adjust to – life is about how we navigate the waves of our lives. It really is about the journey, not the destination.

For most of my life, I lived for the destination while ignoring the journey. Now, I am learning to enjoy the journey as much as I appreciate the destination.

Additional Resources

- National Eating Disorders Association: https://nationaleating disorders.org

- Bulimia Nervosa. University of Maryland Medical Center: http://umm.edu/health/medical/altmed/condition/bulimia-nervosa

- Bulimia Nervosa Resource Guide: http://www.bulimiaguide.org/default.aspx

- Bulimia Nervosa Health Center. WebMD: http://www.webmd.com/mental-health/eating-disorders/bulimia-nervosa/default.htm

- Bulimia Nervosa. Mayo Clinic: http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/bulimia/basics/definition/con-20033050

- Eating Disorder Recovery: Q&A with Dr Christina Bjorndal – Part 1: http://blogs.psychcentral.com/weightless/2010/01/eating-disorder-recovery-qa-with-dr-christina-bjorndal/

- Eating Disorder Recovery: Q&A with Dr Christina Bjorndal – Part 2: http://blogs.psychcentral.com/weightless/2010/01/qa-on-eating-disorder-recovery-with-dr-bjordnal-part-2/

Christina Bjorndal, ND, graduated from the Canadian College of Naturopathic Medicine in 2005. She is a gifted speaker who draws on her many personal and inspirational stories to motivate, inspire, and uplift audiences. Having overcome many challenges in the sphere of mental health, Dr Chris is especially enthusiastic in sharing her motivational speeches about how to overcome barriers in life and to encourage others to achieve their full potential. She is currently completing a book on mental health. Website: www.drchrisbjorndal.com

Christina Bjorndal, ND, graduated from the Canadian College of Naturopathic Medicine in 2005. She is a gifted speaker who draws on her many personal and inspirational stories to motivate, inspire, and uplift audiences. Having overcome many challenges in the sphere of mental health, Dr Chris is especially enthusiastic in sharing her motivational speeches about how to overcome barriers in life and to encourage others to achieve their full potential. She is currently completing a book on mental health. Website: www.drchrisbjorndal.com

References:

- Cox LM, Blaser MJ. Antibiotics in early life and obesity. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2014 Dec 9. [Epub ahead of print]

- Blinder BJ, Cumella EJ, Sanathara VA. Psychiatric comorbidities of female inpatients with eating disorders. Psychosom Med. 2006;68(3):454-462.

- Ross J. The Diet Cure. Available at: http://www.dietcure.com/aminoacids.html. Accessed November 5, 2014.

- Mehler PS, Crews C, Weiner K. Bulimia: medical complications. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2004;13(6):668-675.

- Dejong H, Perkins S, Grover M, Schmidt U. The prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome in outpatients with bulimia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2011;44(7):661-664.

- Scarlata K, Anderson ME. Eating Disorders and GI Symptoms — Understand the Link Between Them and How to Treat Patients. Today’s Dietitian. 2014;16(10):14. Available at: http://tinyrul.com/kudyo3b. Accessed December 15, 2014.

- Consequences of Eating Disorders. Eating Disorder and Referral Information Center. Available at: http://www.edreferral.com/consequences_of_ed.htm. Accessed January 15, 2015.

- Wilson GT. Cognitive Behavioral Treatment of Bulimia Nervosa. The Clinical Psychologist. 1997;50(2):10-12. Available at: http://www.apa.org/divisions/div12/rev_est/cbt_bulimia.html. Accessed November 15, 2014.

- Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Eating Disorders. Eating Disorders Health Center. WebMD Web site. http://www.webmd.com/mental-health/eating-disorders/cognitive-behavioral-therapy-for-eating-disorders. Accessed November 15, 2014.

- Padesky C, Greenberger D. Mind Over Mood: Change How You Feel by Changing the Way You Think. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 1995.

- Hansen K. The Brain Over Binge Workbook. Available at: http://brainoverbinge.com/. Accessed November 15, 2014.

- Kratina K. Orthorexia nervosa. National Eating Disorders Association Web site. https://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/orthorexia-nervosa. Accessed November 15, 2015.