Kathryn Retzler, ND

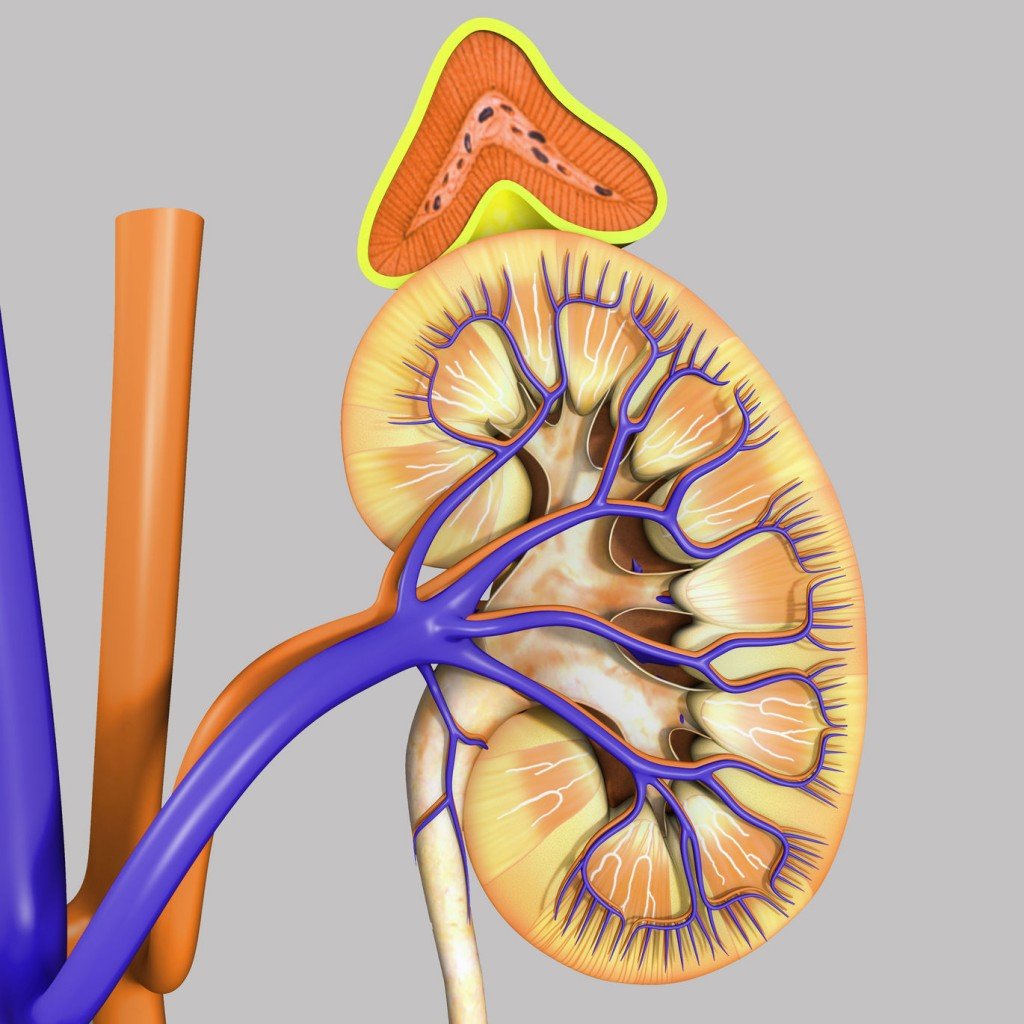

Many clinicians have observed the increased severity of menopause-related symptoms in patients who have experienced chronic stress. Since the adrenal glands “take over” sex hormone production postmenopausally, holistic treatment for menopausal symptoms necessitates optimizing adrenal gland function. This article explains hormone changes during the menopausal transition, testing of stress hormones to help determine treatment and enhance compliance, as well as steps to consider for optimizing adrenal gland function.

Menopause Defined

Menopause is permanent cessation of menses for 12 months due to declining ovarian function. Most women in the U.S. experience some symptoms as menopause approaches, and many symptoms can persist for years after menses cease. Eighty to 85% of women in the U.S. experience vasomotor symptoms during the menopausal transition; 20% to 50% continue to have them for several years after menopause. An estimated 10% to 40% of menopausal women experience symptoms related to vaginal atrophy and vaginal dryness. Other common signs and symptoms in peri/postmenopausal women include:

- Memory problems

- Mood instability

- Weight gain

- Sleep disturbances

- Low libido.

In addition, postmenopausal women have an increased risk for bone loss, cardiovascular disease and cognitive impairment.

Hormone changes during the menopausal transition include declining estrogen (estradiol and estrone) and progesterone levels, as well as lower DHEA, DHEA-S and testosterone production. Since most symptoms of menopause are attributed to sex hormone deficiency, it seems advantageous to discuss the relationship between the adrenal glands and steroid sex hormone synthesis in peri/postmenopausal women. In addition, naturopathic philosophy provides an ideal framework for the prevention and comprehensive treatment of menopausal symptoms through support of healthy adrenal gland function.

Hormone Changes During Menopausal Transition

Waning ovarian function for one to several years preceding the cessation of menses causes estradiol levels to fluctuate significantly. This usually occurs when a woman is in her mid to late 40s, and is characterized by irregular periods. Continually decreasing estradiol levels are associated with an increase in the severity of vasomotor symptoms (see Chart 1). In addition, due to increasingly frequent anovulatory cycles, progesterone synthesis decreases or is absent (most progesterone is made by the corpus luteum after ovulation; however, the adrenal glands do produce small amounts of progesterone). Lastly, DHEA and DHEA-S production decrease with advancing age (referred to as “adrenopause”).

After menopause, the adrenal glands produce androstenedione, which is converted peripherally into estrone by the aromatase enzyme found mainly in adipose tissue. Estrone is then converted into estradiol, the most potent estrogen. Body mass is directly correlated with the rate of peripheral production of estrone and estradiol in postmenopausal women. Therefore, an obese woman may produce much more estrone and estradiol than a thin woman. This may help explain the higher risk of osteoporosis observed in thin women. Besides being a precursor for estradiol and estrone synthesis, androstenedione is also converted into testosterone. Testosterone, in turn, can undergo aromatization to estradiol (see Chart 2).

Serum DHEA-S concentrations in adult women are 100 to 500 times that of testosterone, and 1,000 to 10,000 times that of estradiol. DHEA and DHEA-S levels are highest in the mid-teens to early 20s, gradually decreasing so that by age 70 to 80, values are 20% that of peak levels. DHEA and DHEA-S are considered inactive precursors, since no known receptors for them have been identified. DHEA can be converted into androgens or estrogens, or both; therefore, DHEA may serve as a “reservoir” for steroid sex hormone production.

Since the sources of precursors for estrogens and testosterone (androstenedione and DHEA) and progesterone are produced by the adrenal glands in postmenopausal women, it seems reasonable to assume that optimal adrenal gland function is needed for a smooth menopausal transition and to remain symptom free during postmenopausal years. If the adrenal glands must preferentially make high amounts of cortisol and DHEA due to chronic stress, they may not be able to keep up with the demand for sex hormone precursors. In addition, high cortisol production has been associated with bone loss in both men and women. Furthermore, increased cortisol and epinephrine raise the body’s core temperature. Once the core temperature rises above the thermoneutral zone (above which we sweat and below which we shiver), hot flashes can be triggered as a way to get rid of excess heat.

Adrenal Support as Prevention and Treatment

Naturopathic philosophy recognizes the innate wisdom of the body and its attempts to facilitate preferred tendencies. Supporting healthy adrenal function before and during the menopausal transition can enable the adrenal glands to optimally perform their job in the production of sex hormone precursors. This process can be addressed in the following three steps:

1) Identify stressors and improve stress management. This first step honors the naturopathic tenets of tolle causam, “prevention is the best cure” and docere. Helping patients differentiate between beneficial stress (eustress) and detrimental stress (distress) is important. Hans Selye, in The Stress of Life, defined stress as the non-specific response by the body to any demand placed on it. Although the body’s physiological response to both eustress and distress is similar, the fact that eustress causes much less damage than distress demonstrates that a person’s response to stressful events is fundamental in determining its impact. Supporting patients in identifying and minimizing distress is paramount. This may include referral to a therapist for ongoing counseling; or recommending stress management tools, such as massage and craniosacral therapy, meditation, deep abdominal breathing and/or yoga. I use a “stress thermometer” – a simple biofeedback thermometer that determines peripheral body temperature – to provide feedback to patients about when they are stressed, and to retrain the nervous system to emphasize parasympathetic activity to initiate the relaxation response.

A small study recently published in Menopause showed the value of stress management tools for relief of menopausal symptoms. Fifteen postmenopausal women who were experiencing an average of at least seven moderate to severe hot flashes per day were enrolled in an eight-week stress reduction program. The program consisted of eight weekly 2½ hour classes where participants received the following training:

- Body scan: a slow moving of attention throughout the body from feet to head to enhance awareness of body sensations, performed while lying on the back

- Sitting meditation: focusing on the flow of breathing and other bodily sensations, thoughts and emotions while sitting upright

- Mindful stretching: exercises designed to develop awareness during movement.

The women also received two guided meditation CDs to practice at home. The study resulted in 45% decrease in hot flash severity and 28% improvement in overall quality of life. Most women indicated that they were better able to cope with their hot flashes after the stress-reduction program.

2) Test stress hormones to determine adrenal gland function. Selye was the first to articulate a model for the body’s response to acute and prolonged stress – termed the General Adaptive Syndrome. The first phase, the “alarm phase,” is the initial fight-or-flight response to an acute stressor. Phase two, “resistance,” involves the HPA axis and an increase in DHEA and cortisol output. The third phase, “exhaustion,” occurs when the body can no longer keep up with the demand for adrenaline and stress hormone synthesis.

Testing salivary DHEA/DHEA-S and cortisol levels throughout the day can determine how effectively patients respond to stressors. Salivary hormone testing for stress hormones is very reliable, and is preferred to serum testing, which necessitates venipuncture, a stressful event that influences the results. A patient with high DHEA-S and cortisol levels – a normal response to stress – may not need the same treatment as a patient with low levels of these hormones. If salivary hormone testing determines that DHEA-S and cortisol levels are low, the patient may be in the exhaustion phase, and may have severe fatigue and menopausal symptoms. Testing stress hormone levels can offer the patient a blueprint of the impact that stress has on her body and, therefore, can enhance compliance with recommended lifestyle changes and therapies. In addition, repeat testing of DHEA-S and cortisol levels can enable the physician to monitor treatment effectiveness.

3) Incorporate nutrient, botanical and hormone supplementation. The naturopathic tenet of honoring the vis medicatrix naturae is upheld with the use of nutrients, botanicals and, if needed, bioidentical hormones to support and restore normal adrenal gland function.

Nutrients that support normal adrenal gland function and energy production include:

- Vitamin C: steroid hormone, epinephrine and norepinephrine synthesis

- Vitamin B1: carbohydrate metabolism and ATP production

- Vitamin B5: DHEA and cortisol synthesis and ATP production

- Vitamin B6: epinephrine and norepinephrine synthesis

- Magnesium: ATP production

- Tyrosine: norepinephrine and epinephrine synthesis.

Adaptogenic botanicals improve the response to and recovery from stress. Glycyrrhiza glabra, for example, can inhibit 11 beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase, the enzyme responsible for cortisol degradation. Therefore, it can be very helpful to increase cortisol when levels are low. The list of other adaptogenic botanicals is lengthy and includes Eleutherococcus senticosus, Cordyceps sinensis, Panax ginseng, Rhodiola rosea and Withania somnifera.

Besides nutrients and botanicals, bioidentical hormone supplementation may be indicated to support or restore adrenal gland function. In some instances, hydrocortisone (bioidentical cortisol) may be needed; however, the use of hydrocortisone may suppress endogenous cortisol synthesis and should be reserved for cases of adrenal insufficiency (low cortisol levels throughout the day).

As noted in Chart 1, progesterone is the precursor for cortisol synthesis. In anovulatory pre/postmenopausal women, very little progesterone is available. If the demand for cortisol exceeds progesterone availability, low cortisol output can result. Supplementing with low-dose, bioidentical progesterone, such as topical or oral micronized, or Prometrium may be valuable in cases of chronic stress, where demand for stress hormones exceeds production.

In postmenopausal women, DHEA is the precursor for androstenedione and, therefore, for testosterone, estradiol and estrone. Women with low libido and other symptoms of sexual dysfunction have been shown to have low DHEA levels. In postmenopausal women, DHEA supplementation has been shown to improve hot flashes, as well as sexual dysfunction, depression and overall well being. In addition, plasma DHEA, DHEA-S, estrone, androstenedione, testosterone and DHT levels increase with DHEA supplementation. A recent study in the New England Journal of Medicine supported the finding that DHEA supplementation increases DHEA-S and testosterone levels in women, and may be helpful for androgen deficiency symptoms, such as vaginal dryness, low libido and decreased bone density.

Naturopathic medicine encourages physicians to treat underlying causes of a patient’s symptoms. A comprehensive understanding of hormone physiology in pre- and postmenopausal women is necessary to understand why symptoms develop, and to focus treatment appropriately. Considering the steps outlined above can enable physicians to offer safe and effective therapeutic options that uphold the tenets of naturopathic medicine.

References

Larsen PD et al (eds): William’s Textbook of Endocrinology, ed 10, Philadelphia, Saunders, 2003.

Ravn P et al: Low body mass index is an important risk factor for low bone mass and increased bone loss in early postmenopausal women. Early Postmenopausal Intervention Cohort (EPIC) study group, J Bone Miner Res Sept;14(9):1622-7, 1999.

Reynolds RM et al: Cortisol secretion and rate of bone loss in a population-based cohort of elderly men and women, Calcif Tissue Int Sept;77(3):134-8, 2005.

Carmody J et al: A pilot study of mindfulness-based stress reduction for hot flashes, Menopause. Sept/Oct(13): 760-769, 2006.

Gozansky WS et al: Salivary cortisol determined by enzyme immunoassay is preferable to serum total cortisol for assessment of dynamic hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity, Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 63(3):336-41, 2005.

Cook, CJ: Rapid noninvasive measurement of hormones in transdermal exudate and saliva, Physiol Behav Feb 1-15;75(1-2):169-81, 2002.

Genazzani AD et al: Long-term low-dose dehydroepiandrosterone oral supplementation in early and late postmenopausal women modulates endocrine parameters and synthesis of neuroactive steroids, Fertil Steril Dec;80(6):1495-501, 2003.

van Vlijmen JC et al: Dehydroepiandrosterone replacement in women with adrenal insufficiency, N Engl J Med Sep 30;341(14):1013-20, 1999.

Nair SK et al: DHEA in elderly women and DHEA or testosterone in elderly men, The New England Journal of Medicine, Oct19;355(16):1647-59, 2006.

Kelly GS: Nutritional and botanical interventions to assist with the adaptation to stress, Alt Med Review 4(4):249-265, 1999.

Bland J: Breakthrough approaches for improving adrenal and thyroid function (seminar syllabus), Institute for Functional Medicine 2002: 1165-169, 2002.

Wilson JL: Adrenal Fatigue: the 21st Century Stress Syndrome, Petaluma, 2001, Smart Publications.

Jeffries W: Safe Uses of Cortisol, Springfield, 1996, CC Thomas.

Kathryn Retzler, ND is a graduate of NCNM. She completed an internship with Andrew Weil, MD at the University of Arizona’s Integrative Medicine Program and a residency with Bruce Dickson, ND in McMinnville, Ore. Dr. Retzler currently is a part-time clinical consultant at ZRT Laboratory, where she provides support to physicians and pharmacists about hormone testing and bioidentical hormone supplementation. She also has a private practice in Portland, with a focus on hormone balance and neurotransmitter optimization, and facilitates groups on healthy detoxification and ideal weight naturally.

Kathryn Retzler, ND is a graduate of NCNM. She completed an internship with Andrew Weil, MD at the University of Arizona’s Integrative Medicine Program and a residency with Bruce Dickson, ND in McMinnville, Ore. Dr. Retzler currently is a part-time clinical consultant at ZRT Laboratory, where she provides support to physicians and pharmacists about hormone testing and bioidentical hormone supplementation. She also has a private practice in Portland, with a focus on hormone balance and neurotransmitter optimization, and facilitates groups on healthy detoxification and ideal weight naturally.