Marnie Loomis, ND

Node Smith, ND Candidate

A wrong functioning of the psyche can do much to injure the body, just as conversely a bodily illness can affect the psyche; for psyche and body are not separate entities, but one and the same life.

-C. G. Jung, 1917

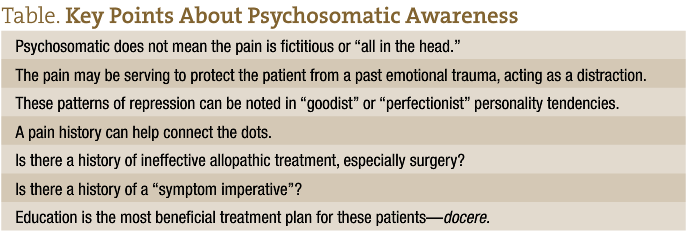

A fair amount of resistance to psychosomatic disorders exists in the United States. The idea that a patient can experience real physical symptoms of chronic back pain, bowel discomfort, or migraine headaches that could be explained by a root psychological cause seems preposterous to many patients and clinicians alike. Historically, this could be accounted for by the initial assumption that a psychosomatic diagnosis meant the pain or discomfort was “all in the mind.” No patients want to be told that their symptoms are not real, that they are “creating” them. In addition to being incorrect, language such as this has an inherent air of judgment, which undermines any therapeutic intention, whether vocalized by the physician or merely supported by dominant cultural views about psychological diagnosis. Movement is toward a new understanding of psychosomatic disorders, especially chronic pain disorders.

Chronic pain plagues millions of people, and its effects are truly devastating. Many individuals experiencing chronic pain disorders will spend years of their lives shuttled from specialist to specialist, without resolution from allopathic treatment.1-3 These patients have very real pain. It is not all in their minds, but perhaps it does originate there.

Part of the difficulty in treating chronic pain disorders such as chronic low back pain is the absence of a structural abnormality that definitively accounts for the pain. In some cases, structural abnormalities are incorrectly diagnosed as the cause of pain, leading to invasive surgical procedures that fail to take the pain away.3,4 Psychosomatic diagnosis and treatment may be able to provide much-needed relief for these patients, provided they are educated about the delicate and very real interplay between the mind and body in a way that addresses the previously mentioned fallacy. Many of these patients for whom allopathic treatment has failed will seek “alternative” methods of pain management.5 Naturopathic physicians may be in the perfect position to serve as true advocates for what the fringes of the allopathic community call a much-needed “paradigm shift”6 in the perception and interpretation of chronic pain.

This article aims to present a possible psychosomatic mechanism behind chronic low back pain that may be used to educate patients who are initially resistant to the idea of psychogenic pain. The diagnosis of chronic pain as a psychosomatic disorder has been termed tension myositis syndrome (TMS)7 and is arguably the best-understood psychosomatic disorder.

Tension Myositis Syndrome

Tension myositis syndrome, a condition first described by John Sarno, MD,7 in the mid 1970s, describes repressed emotions as the most likely underlying factor in chronic pain. The process typically begins with the repression of a psychologically traumatic event. Pain then manifests as the conscious mind searches for an avenue in which to distract itself from confronting the emotional processing of the event.3 This may sound very cryptic, but it is actually quite simple. Relationships, stressors, and emotionally traumatic events elicit emotional responses. When these emotions are processed in a timely manner, they dissipate from our conscious and subconscious mind alike, never to bother us again. However, when the conscious mind becomes threatened by these emotions or a patient lacks the resources to process through them effectively (or appropriately), the emotions are repressed in an effort to keep them from influencing a current state of reality. This repression can be helpful in acute situations such as an emergency or other instances where conscious processing of an emotional response could negatively affect the outcome of the situation. However, when the emotional response is something that the conscious mind finds too threatening to look at, even after the emotional situation has passed, pain can continue to be used as a physical distraction from the trauma of the emotional event.3 A common and well-understood example of a trauma that triggers this phenomenon is early childhood sexual abuse.

The pathogenesis begins with these repressed emotional processes of the subconscious mind, which triggers abnormal functioning of the autonomic nervous system, most likely via the hypothalamic-pituitary axis.3 This dysregulation can lead to mild regional ischemia and poor oxygenation of tissues, which results in muscle pain, nerve pain, paresthesias, paresis, or tendon pain.8 This top-down mechanism helps explain why many patients who undergo spinal surgery to repair a herniated disc, diagnosed as the cause of their chronic low back pain, often have their pain return shortly after the surgery.3,4 It may initially seem that structural abnormalities are the culprits of pain, but it is very possible that the factors influencing chronic pain are more complex. These potential psychological causes need to be considered before surgery is advocated.

Recognizing TMS

Recognizing psychosomatic pain originating from emotional trauma or repressed emotions may be difficult, even when a strong patient-physician relationship exists. Confounding this problem is the likelihood of a patient’s accepting a psychosomatic diagnosis or treatment. Among all chronic pain cases in which a physician may suspect a psychogenic origin, it has been estimated that only 20% of patients will accept such a diagnosis or follow through with a treatment plan if it centers on their psychology.3 However, for these 20%, a psychosomatic connection may be the breakthrough in their health that truly changes their lives. Once identified, results can be rapid and significant. Many accounts exist of patients’ being cured of low back pain or other chronic pain manifestations after only a short educational session on how psychosomatic disorders operate in the body3,6; this truly speaks to the healing power of docere.

Among patients with chronic pain, TMS can be recognized by objectively assessing a patient’s personality traits (which addresses the manner in which he or she emotes) and the history of the chronic pain.3,6 Patients with TMS often have a long history of chronic pain that is most severe during times of stress or other emotionally intense circumstances.3 Many patients with TMS have undergone previously unsuccessful allopathic treatments for their pain; surgery with little to no improvement in pain level is common. Perhaps the most indicative clue that psychosomatic chronic pain is the culprit is what Sarno3 calls the “symptom imperative,” the phenomenon in which one symptom replaces a previously treated symptom. For instance, perhaps a patient is experiencing hip pain, and after working with a chiropractor for a number of months, the hip pain resolves and is immediately replaced by low back pain or neck pain. The symptom imperative may be at work here. Because of the emotional guarding already explained, the mind has decided it is imperative for the patient to have a physical symptom to distract the conscious mind from emotions in the subconscious. This pattern of “switching” symptoms could be interpreted as if the mind is acknowledging that it needs to allow some therapies to work so as not to draw attention to the overall process that is really the root cause.

In addition to these typical pain histories, a normative TMS personality type seems to exist. Keeping in mind how the psychology of TMS operates, typical patients will display what some have referred to as “goodist” or “perfectionist” tendencies.3 These individuals are often very driven, thriving on success and fast-paced work environments; they are often very perfecting, which may affect relationships or their happiness with work and relationships. Psychosomatic disorders are also commonly correlated with anxiety disorders.9,10 These individuals will often describe themselves as not getting angry or not letting their emotions get involved in their lives. These patients may actually experience the greatest degree of confusion as to how emotions are aggravating their pain. What needs to be remembered is that the problem is the repression of these emotions, which need to be processed but are being pushed into the subconscious instead; the patient will not be consciously aware of them.

Physicians who diagnose and treat TMS use various questionnaires to objectively assess the likelihood of a psychosomatic cause of the pain, taking both the pain history and the personality type into account.6 These include Dr John Sarno and Dr David Schechter, both cited in this article.

Treatment of TMS

The treatment of TMS relies on skillful education of the patient.3 The idea behind treating patients with TMS is that, once they are aware of the mechanism behind their pain, the conscious mind will no longer be able to use pain as a means of distraction from underlying emotions. It deserves mention that emotional trauma may exist on a continuum to the objective eye of the physician, but to the patient it does not. Whether a patient is repressing childhood sexual abuse or the fear of seeming inadequate at performing certain tasks at work, these repressed emotions are terrifying to those who are experiencing them. In many cases, merely reading a book (such as Healing Back Pain by Dr Sarno11) will bring about such an awareness that their pain will cease. However, additional education is needed in most cases, and a patient might attend a series of group lectures on psychosomatic disorders,3 use guided journal entries to connect with underlying emotional trauma, or undergo a series of educational office visits. Few patients end up needing psychotherapy.3,6 An important aspect of this educational process is the severing of belief that a physical abnormality is the cause of pain. This may mean urging the patient to stop seeking manipulative treatment and instead advocating him or her to resume normal physical activity.3

Although TMS was exclusively discussed herein, other disorders have strong clinical support for being regarded as psychosomatic. Fibromyalgia, irritable bowel syndrome, migraine headaches, allergies, and asthma have all been thought to have some psychosomatic underpinnings.3,10,12,13 The emotional-physical pathogenesis of these disorders is the same; however, different organ systems may be involved in addition to the hypothalamic-pituitary axis, including the enteric system, respiratory system, or neuroimmune system.10,12,13

Marnie Loomis, ND is the director of professional formation and career services and an adjunct faculty member at the National College of Natural Medicine, Portland, Oregon. She enjoys writing and is a popular public speaker who appears on local TV news programs and in front of professional and public audiences throughout the country. Before joining NCNM, Dr Loomis had a private naturopathic medical practice in Aloha, Oregon, and was the managing editor of Naturopathic Doctor News & Review.

Marnie Loomis, ND is the director of professional formation and career services and an adjunct faculty member at the National College of Natural Medicine, Portland, Oregon. She enjoys writing and is a popular public speaker who appears on local TV news programs and in front of professional and public audiences throughout the country. Before joining NCNM, Dr Loomis had a private naturopathic medical practice in Aloha, Oregon, and was the managing editor of Naturopathic Doctor News & Review.

Node Smith is currently an ND candidate at National College of Natural Medicine (Portland, Oregon). He graduated from Western Washington University (Bellingham) in 2006 with a degree in literature and an emphasis in critical theory. He considers philosophy and psychology the key ingredients to forming an understanding of how “normal” interactions can become healing interactions and is looking forward to a long and nourishing career in natural medicine. He would like to thank all those who have paved the road of naturopathy to date and is very excited to be helping with the effort to expand the healing arts in America.

Node Smith is currently an ND candidate at National College of Natural Medicine (Portland, Oregon). He graduated from Western Washington University (Bellingham) in 2006 with a degree in literature and an emphasis in critical theory. He considers philosophy and psychology the key ingredients to forming an understanding of how “normal” interactions can become healing interactions and is looking forward to a long and nourishing career in natural medicine. He would like to thank all those who have paved the road of naturopathy to date and is very excited to be helping with the effort to expand the healing arts in America.

References

Hansson TH, Hansson EK. The effects of common medical interventions on pain, back function, and work resumption in patients with chronic low back pain: a prospective 2-year cohort study in six countries. Spine. 2000;25:3055-3064.

Croft PR, Macfarlane GJ, Papageorgiou AC, Thomas E, Silman AJ. Outcome of low back pain in general practice: a prospective study. BMJ. 1998;316:1356-1359.

Sarno JE. Divided Mind. New York, NY: Harper Collins; 2006.

Stimson BB. The low back problem. Psychosom Med. 1947;9(3):210-212.

Deyo RA, Weinstein JN. Low back pain. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:363-370.

Schechter D, Smith AP, Beck J, Roach J. Outcomes of a mind-body treatment program for chronic back pain with no distinct structural pathology. Alt Ther Health Med. 2007;13(5):26-35.

Sarno JE. Psychosomatic backache. J Fam Pract. 1977;5(3):353-357.

Rashbaum IG, Sarno JE. Psychosomatic concepts in

chronic pain. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;84(3)

(suppl 1):S76-S82.

Dersh J. Chronic pain and psychopathology: research findings and theoretical considerations. Psychosom Med. 2002;64(5):773-786.

Greenberg DB, Braun IM, Cassem NH. Functional somatic symptoms and somatoform disorders. In: Stern TA, Rosenbaum JF, Fava M, Biederman J, Rauch SL, eds. Massachusetts General Hospital Comprehensive Clinical Psychiatry. St Louis, MO: Mosby; 2008:319-330.

Sarno JE. Healing Back Pain: The Mind-Body Connection. New York, NY: Grand Central Publishing; 1991.

Dimsdale JE, Dantzer R. A biological substrate for somatoform disorders: importance of pathophysiology. Psychosom Med. 2007;69(9):850-854.

Groopman J. Hurting all over. The New Yorker. November 13, 2000.