Steven Sandberg-Lewis, ND, DHANP

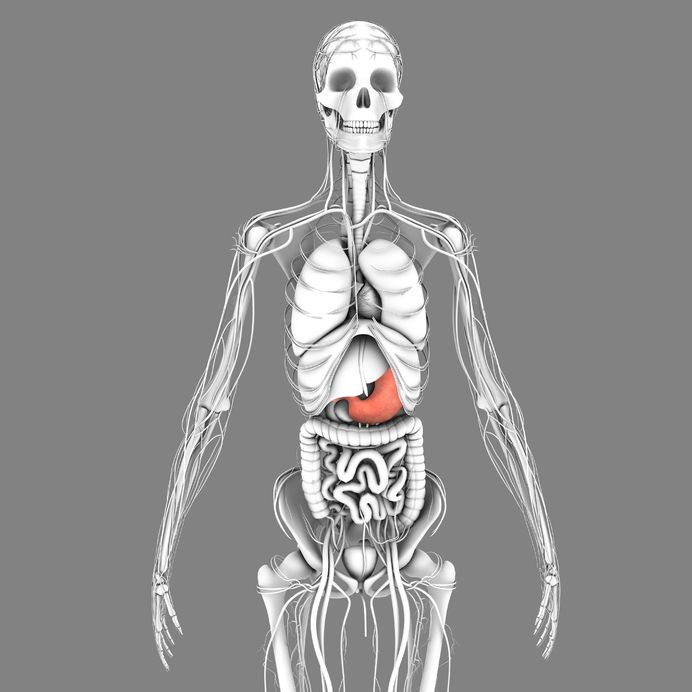

Hiatal hernia syndrome (HHS) is one of the most common functional GI disorders. Patients manifesting this functional condition may present with gastroesophageal reflux symptoms; the syndrome may also be a trigger for asthmatic bronchoconstrictive episodes.

A patient may already have had an upper GI barium study or endoscopy (esophagogastroduodenoscopy), which may not reveal organic disease/hiatal hernia. This does not preclude the possibility that the ND will detect this syndrome.

The recognition and management of this syndrome was greatly advanced by the work of Dr. Ralph Failor, a naturopathic and chiropractic physician who practiced in Hillsboro, Ore. during the last half of the 20th century. This syndrome is a functional relative to the true hiatal hernia, a gastric pathology in which the proximal stomach is herniated into the mediastinum. Hiatal hernia syndrome is distinguished by the fact that the proximal stomach may only cause upward pressure against the diaphragmatic hiatus and not actually protrude into the chest.

I get many referrals for this condition, and by using the technique discussed in this article, the relief for patients is often immediate and dramatic. You can also use this technique to treat a true hiatal hernia.

Possible symptoms are the same for both the true hernia and the syndrome. These may include:

- Fatigue

- Mental dullness

- Easy satiety

- Shallow thoracic breathing

- Relatively rapid respiratory rates

- Globus sensation

- Dysphagia

- Chest oppression

- Reflux

- Stitching chest pains

- Regurgitation

- Aversion to constriction at the waist

- Flatulence

- “Spare tire” bulge just below the inferior margin of the ribs

- Tickling, non-productive cough

Etiology

This syndrome may be due to an inherited wide diaphragmatic hiatus or may be acquired from trauma or increased intra-abdominal pressure. Examples of trauma include abdominal surgery, the impact of jumping or falling from a height, horseback riding, strenuous abdominal exercise, a blow to the abdomen or a “belly flop” dive, or merely exertion with breath holding.

An increase in intra-abdominal pressure may also be due to pregnancy or abdominal obesity, or any space-occupying lesion of the abdomen.

Diagnosis

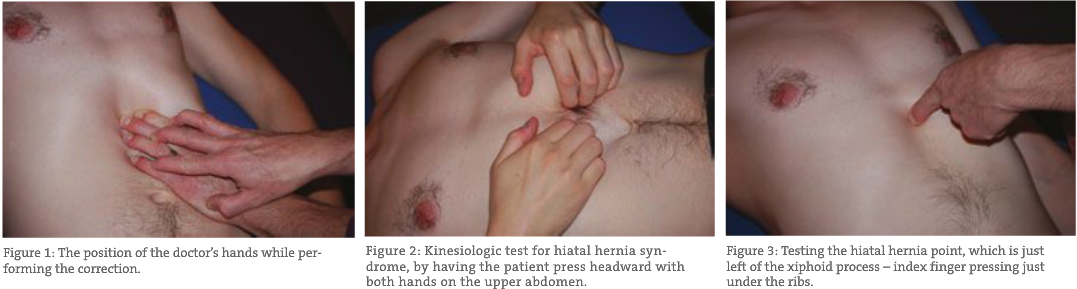

Dr. Failor used the following tender points for detection of the syndrome:

- Reflex points

– Left of xiphoid (HHS point)

– 4th ICS mid clavicular

– 4th ICS mid axillary

– T10-11 left paravertebral area

I ask the patient to rate these on a 0-4 scale and reassess after treatment.

Another method that I have found very useful is an applied kinesiology test:

- Find any muscle that tests strong (I often use the rectus femoris)

- Retest the strong muscle while having the patient use both hands to press the upper abdomen inward and cephalad (which increases the pressure of the proximal stomach against the diaphragm).

If the muscle weakens, this is a positive indicator.

Treatment

Treatment of the syndrome (or an actual sliding hiatal hernia) involves the following:

Visceral manipulation. Dr. Failor taught us his technique in 1977 and many doctors still use it. It’s effective, but can be a bit forceful. I trained in structural integration in 1996, and over the last five years I have developed a gentler method.

I contact the epigastric area just inferior to the costosternal angle. I use a “claw” hand contact and support the contact hand with my other hand (see Figure 1). I traction toward the left ASIS and wait for the soft tissue to begin a counterclockwise rotation. I just allow my fingers to follow the movement while continuing to apply the traction. In most cases, the rotation will shift to clockwise as I continue the traction. When the rotation is finished (usually 2 to 4 minutes at the longest), I add three additional clockwise thrusts of my hands (see Figure 2). Dr. Failor called this “ballooning the stomach” and felt that it was important for the manipulation to hold.

Any additional techniques an ND might already use to free the thoracic vertebrae, ribs and diaphragm muscle in general are helpful, should they be necessary. Dr. Failor found that T10 and T11 were especially important, so I tend to check there. In addition, the occiput is often an essential area to check and correct. The basic “cranial base release” is effective; or you can use myofascial or other cranial techniques or osseous manipulation if you prefer. In addition, check C3, C4 and C5, which innervate the diaphragm.

After treatment, recheck the tender point or use kinesiology testing. The change should be immediate.

Post-Manipulation Exercises

- Heel drops. The patient drinks (not sips) 12-16 ounces of warm water on waking, stands and rises onto his or her toes and then drops onto the heels eleven times in succession. The downward momentum of the water-filled pendulous stomach supports the benefits of the visceral work.

- Leg raise. Lying supine on a flat surface with legs adducted, the patient inhales, and while exhaling raises both legs 12-18 inches, slowly abducts and adducts the legs and then lowers them to the resting position. Have them gradually increase the number of repetitions over time.

- Knee raise. Sitting in a chair, the patient supports the upper body by holding the arms or seat of the chair. Keeping the knees adducted, the patient inhales, then exhales and flexes the legs on the trunk as far as possible. Taking the next breath, they extend the legs and rest their feet on the floor, then exhale as they repeat the procedure. Have them gradually increase the number of repetitions over time.

Dietary basics. In general, I find that having patients avoid their food sensitivities is important. Simplifying meals (simple combinations) is also important. Just as important as what they eat is how they eat. Have the patient:

- Avoid large meals and overeating

- Take time to sit and chew food until it becomes liquid before swallowing (Fletcherizing)

- Avoid stressful discussions or watching television (i.e., news shows) while eating

- If family of origin eating issues are still affecting eating habits, consider counseling or energetic psychology interventions

Treating hypochlorhydria or achlorhydria, if present, is also essential for these patients.

Functional breathing and lifting. This is crucial. Teach these patients functional lifting and exertion. Have them take a slow abdominal breath before exerting and then exhale as they exert. This prevents a buildup of intra-abdominal pressure, thus preventing re-injury.

Developing the skills of hiatal hernia technique and protocols for treatment will gain an ND many referrals and the ability to get rapid, lasting results with many cases of functional esophageal, gastric and diaphragmatic syndromes.

Steven Sandberg-Lewis, ND, DHANP, has been a practicing naturopathic physician since his graduation from National University of Natural Medicine (NUNM) in 1978. He has been a professor at NUNM since 1985, teaching a variety of courses but primarily focusing on gastroenterology and GI physical medicine. His clinic rotations are particularly popular among NUNM doctoral students. In addition to supervising clinical rotations he also maintains a part-time practice at 8Hearts Health and Wellness in Portland, Oregon.

Steven Sandberg-Lewis, ND, DHANP, has been a practicing naturopathic physician since his graduation from National University of Natural Medicine (NUNM) in 1978. He has been a professor at NUNM since 1985, teaching a variety of courses but primarily focusing on gastroenterology and GI physical medicine. His clinic rotations are particularly popular among NUNM doctoral students. In addition to supervising clinical rotations he also maintains a part-time practice at 8Hearts Health and Wellness in Portland, Oregon.

He is a popular international lecturer at functional medicine seminars, presents webinars, writes articles for NDNR and the Townsend Letter and is frequently interviewed on issues of digestive health and disease. He is the author of the medical textbook Functional Gastroenterology: Assessing and Addressing the Causes of Functional Digestive Disorders, Second Edition, 2017, which is available at amazon.com. In 2010 he co-founded the SIBO Center at NUNM which is one of only four centers in the USA for Small Intestine Bacterial Overgrowth diagnosis, treatment, education and research. In 2014 he was named one of the “Top Docs” in Portland monthly magazine’s yearly healthcare issue and in 2015 was inducted into the OANP/NUNM Hall of Fame.

Within gastroenterology, he has special interest and expertise in inflammatory bowel disease (including microscopic colitis), irritable bowel syndrome (including post-infectious IBS), Small Intestine Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO), hiatal hernia, gastroesophageal and bile reflux (GERD), biliary dyskinesia, and chronic states of nausea and vomiting.

Many of the patients referred to Dr. Sandberg-Lewis have digestive conditions that have defied diagnosis and effective resolution. Often these patients desire naturopathic treatment options in lieu of the courses of treatments they have previously undergone. He understands diseases of the gastrointestinal tract, but also can assess function and often find successful treatments to regain a balance in the digestive system.

Dr. Sandberg-Lewis lives in Portland with his wife, Kayle. His interests include mandolin, guitar and voice; cross country skiing; writing and lecturing.

Reference

Failor, RM: The New Era Chiropractor. Self-published, 1979.