Sussanna Czeranko, ND, BBE

To individualize, i.e., combine these various agencies [pure air, proper food, regular exercises, sunlight and baths] into a system, which conforms, with the condition of each individual patient, is the art of the physician.

Carl Strueh, 1913, p.171

The object of the institution is not merely to cure those who are sick, but at the same time teach them the science of health culture. Carl Strueh, 1913, p.393

The method of treatment employed at Dr. Strueh’s Sanatorium embraces all rational natural agencies, such as the Water Cure (Hydrotherapy) in its various forms, Diet Cures, Sun and Air Baths, Physical Calisthenics, Massage, Rest Cure, in fact the complete Regeneration Cure.

Carl Strueh, 1916, p.302

In earlier articles, I have often described the Return to Nature trend initiated by Adolf Just’s book of the same title, published in 1896 in Germany. Who could have guessed, at the point of its publication, that this book would be a catalyst for a movement that crossed oceans and land masses like a seismic shock wave within months of being published. A century ago, communication depended upon telegraphs, local papers. The progress of media depending on such analog technology as Morse code, or on the transport of boats, rail, and early cars and trucks was steady, but slow. Motorized vehicles shared the road with horse-drawn vehicles in this era, and they both moved along unimproved roads (or the few miles of paved roads) at the turn of the 20th century, traveling at a robust average speed of 8 mph. Information and ideas traveled slowly in comparison to our modern, ubiquitous, instantaneous global community, linked by the worldwide web, massive shipping lanes, freeways, jet transport, and Wi-Fi hot spots.

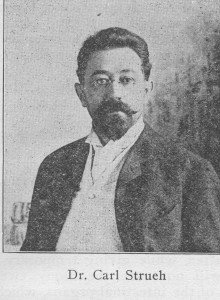

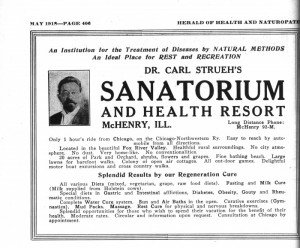

During this earlier but nevertheless remarkable era of transformation, Carl Strueh (Figure 1) emerged as another early pioneer, coming out of the late 19th century health movement. Born in 1861 in Hildesheim, Germany, he was destined to leave a powerful mark upon Naturopathy, both in his clinical contributions and his publications in The Naturopath and Herald of Health. The historical data show that he was an unlikely candidate for Naturopathy, since he began his medical studies as an allopath in Germany’s medical hub of Göttingen, Zürich, and München Universities. (Miller, 1907, p.84) Earlier in his career, Dr Carl Strueh even wrote several allopathic medical books, which earned him much recognition by colleagues and a coveted position as an assistant professor in the University Hospital in Zürich. Later, though, his philosophy and his geography shifted. He came to America, choosing Chicago, where he was soon buoyed by a large contingency of German immigrants; he there soon established an ideal site to reside and practice medicine – naturopathic medicine.

From Germany to Chicago

Strueh’s first Chicago clinic specialized in chronic diseases at 464 Belden Avenue in 1897 (Figure 2). (Miller, 1907, p.85) As more and more patients presented, he soon became “disgusted with the drug treatment, which he considered the most fallacious method of treating diseases and which he considered as the greatest curse with which humanity is afflicted at the present day.” (Miller, 1907, p.84) He soon replaced drug treatment with many of the therapies used by the early Naturopaths, including “Kneipp water treatments, diet, massage, air and sun-baths, rest cures, Thure Brandt’s massages for female diseases, physical culture, orthopedics, pneumotherapy and electrotherapy.” (Miller, 1907, p.85)

Strueh began his medical practice in Chicago 1 year after Benedict Lust began publishing his first journal, Amerikanse Kneipp Blätter, in New York City. These 2 men would spend many years of their lives changing the fabric of medicine dramatically. Benedict Lust would champion Naturopathy nationally, and Carl Strueh was one of his strongest colleagues and allies regionally, transforming the meaning of health from his remarkable base in the Midwest.

Strueh was attracted to the notion of the healing virtues of Nature, soon understanding them to constitute a central tenet and key element of Naturopathy. He soon embraced completely this approach within his clinical practice. Strueh learned quickly from his colleagues. He was a shrewd observer, and writer:

Most all of us are living unnatural lives. We spend most of our time in doors away from sunlight and pure air and exposed to an overheated and impure atmosphere, we lack exercise or on the other hand, overwork ourselves physically, or mentally, we do not eat the proper food or eat it in the proper way, we indulge in all sorts of excuses, deny ourselves natural sleep, we worry most of the time, in short live wrong in every way possible. (Strueh, 1913, p.170)

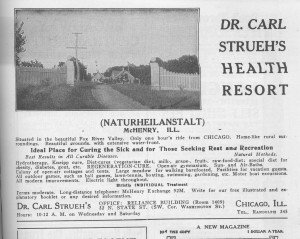

Living in the noisy bustle of Chicago awakened in Strueh the realization that Nature was missing in medical treatments and the promotion of health, not only for himself but also for his patients. A man of action, by 1907 Strueh moved his city clinic to 100 State Street and began planning a health retreat for his patients. Having the vision and means, Strueh did something about the lack of Nature and, like Lust, built a “Yungborn.” He too chose a rural setting, gradually establishing his center “on a 30 acre tract in the beautiful Fox Valley, far enough from the windy, dusty city and yet close enough to reach Chicago inside of 60 minutes.” (Miller, 1907, p.85) Recognizing, too, that the Vis medicatrix naturae – the healing powers that exist inside of us – Strueh incorporated within his armamentarium 5 simple elements: “pure air, proper food, regular exercises, sunlight and baths.” (Strueh, 1912, p.171) He also recognized that “there is no greater obstacle to the progress of recovery than worry, and no more powerful aid than a cheerful disposition.” (Strueh, 1913, p.389) With these principles and ideas in mind, he strived “to make the patient’s surroundings as pleasant as possible and, by eliminating everything that is suggestive of a hospital, cultivate a health-inspiring spirit which is bound to greatly increase the effectiveness of the treatment.” (Strueh, 1913, p.389)

In 1907 Benedict Lust visited Chicago and visited Strueh’s site, at that point just an idea and not yet actualized. Five years later Lust returned and quickly praised Strueh’s achievements, declaring, “The buildings are so numerous, large and small and the first glance you get of it reminds you more of a little town or village than an institution.” (Lust, 1912, p.320) In his enthusiasm for the venue, Lust adds, “In the evening when all the cottages and grounds are lit up with electric lights a look from the river through the grove which stretches all along the water, makes you imagine to be in Fairyland. And to think that all this has been done within five years.” (Lust, 1912, p.376)

Lust continues, “Dr. Strueh is one of those pioneers, who by his writings in popular and medical magazines and books, and other deeds, has done his full share to help Nature Cure to be recognized and respected, not only by the laity, but by the physicians as well.” (Lust, 1912, p.376) Strueh had maintained his professional alliances and was a “member of the leading medical societies, such as the Chicago Medical Society, the Illinois State Medical Society, the American Medical Association, the German Medical Society of Chicago, etc.” (Lust, 1912, p.376)

The sanitarium that Carl Strueh built was 45 miles, or an hour away, from the hectic flurry of Chicago. It had many of the typical features that we have seen in Louisa and Benedict Lust’s Yungborn in Butler, New Jersey, and in many European sanitariums of this period. Strueh promoted constantly his Orchard Beach Sanatorium in Lust’s publications, and left behind for us in the literature valuable clues as to the naturopathic core philosophical tenets guiding his activities and the therapies delivered to his patients.

In 1908, Strueh wrote an article entitled, “The Need of a Vacation.” Within a few short years his Sanatorium would provide health cures and opportunities for his patients to relax. He comments on people’s tendency to ignore their health and to overwork. He describes clearly the conundrum for those caught in busy lives in unnatural environments:

We are all slaves to unfavorable conditions or to foolish habits. The great majority of us sacrifice the largest part of our lives and our health to the fight for mere physical existence. And when at last we have succeeded in getting into quiet water, we complete our self-destruction by indulging in all kinds of good things. (Strueh, 1908, p.125)

He adds, “To spend most of our time, as the majority of us do, in stuffy offices, stores or shops, and in overheated and poorly ventilated living and sleeping rooms is against the very first principle of health culture and will, in the course of time, lead to disastrous results.” (Strueh, 1913, p.390) Guided by Nature’s laws and as a true Naturopath, Strueh was quick to identify the core problem, and remarks, “We are constantly violating every one of the simple but rigid laws which nature has ordered for the preservation of our mental and physical health.” (Strueh, 1908, p.126)

Fresh Air

Fresh air and plenty of it was available for those staying at Strueh’s institution. Breathing fresh air was essential, and Strueh considered that “without pure air there is no healthy blood, and without healthy blood, there is no cure.” (Strueh, 1913, p.390) The guests at Strueh’s sanatorium were also encouraged to adopt a sleeping regime of retiring to bed early. The accommodations provided at the McHenry Sanatorium – another name adopted for Strueh’s establishment – were air huts modeled after Just’s invention (Figure 3). Air huts were built to provide the patient with fresh clean air all the time during his or her stay. “In constructing the sleeping cottages, it has been our aim to provide the most perfect ventilation and thus enable the patient to breathe pure country air every minute of his stay at the institution, day and night.” (Strueh, 1913, p.390)

Individualized Simple Diets

In addition to the salutary benefits of fresh air, another secret to Strueh’s success was nutrition. He writes, “In the first place, I make it a rule to instruct in the principles essential for the preservation of health. My summer guests learn to live on a simplified diet, which is quite different from the rich and coarse food served in the average summer hotel. Complicated menus are tabooed, because they are unhygienic.” (Strueh, 1908, p.126) Strueh made use of all of the dietary regimes that were practiced in his day. They are remarkably consistent with our own. Each patient would be prescribed an individualized diet, most often vegetarian, occasionally including “a mixed diet (with some meat), or raw [vegetarian] food, or fruit, or grape diet, while for some patients a strict fast [was] prescribed.” (Lust, 1912, p.377) Strueh truly understood the importance of patient care. His approach so aptly reflects naturopathic wisdom, then and now. He advocated, “Individualizing, i. e., to adapt the diet to the individual patient and not so much to the character of the disease, is the secret of dietetics.” (Strueh, 1913, p.391) Strueh’s Yungborn provided its guests with fruit from its orchards, milk from its dairy, eggs from its chickens, and vegetables from its gardens.

Physical Culture and Exercise

It does not surprise us, then, that a typical day began “first thing in the morning [with] a barefoot walk in the wet grass… followed with breathing exercises.” (Lust, 1912, p.377) Breakfast was simple and healthy: “fruit, farina, boiled egg, whole wheat bread, or toast, butter, honey, malt coffee and cream.” (Lust, 1912, p.377) Strueh knew that Kneipp had fostered principles such as strict observance of rest following meals, and he applied these at his retreat center. Following breakfast, people rested until 9 AM, when the day would begin with physical culture and exercise. “In the open-air gymnasium, which Dr Strueh has placed in the shady grove, patients are given such exercises as are consistent with their physical strength and the character of their afflictions.” (Lust, 1912 p.378)

Dr Strueh believed strongly in the merits of activity, and enthusiastically endorsed physical culture. In his words, “A sedentary life is the greatest detriment to health, which will manifest itself before we know it. It will lead to chronic diseases, such as diabetes, neurasthenia, rheumatism, etc., or to general debility which will deprive us of all pleasure of life as much as real sickness does.” (Strueh, 1918, p.65) Lust echoed Strueh’s principles on activity: “No health without work! A lazy life leads to misery and premature decline.” (Lust, 1912, p.377) The choices available for the patients included rowing, gardening, tennis, medicine ball, and other outdoor games.

A schedule of a patient’s day indicates that not a moment was wasted. A patient’s day was filled with activity, but there was a sense of balance in the busy agenda. Following a half-hour of exercise, “patients would go to the treatment houses, of which there are two, one for women, and one for men, and take their bath or pack, or massage. Steam baths are more frequently applied on cool days.” (Lust, 1912, p.378) Lust continues with his description of Strueh’s Sanatorium schedule: “After the treatment the patients spend one to two hours in the sun and air bath.” (Lust, 1912, p.378) The air bath was combined with “a systematic drill given under Dr. Strueh’s personal supervision… followed by a refreshing air-bath.” (Lust, 1912, p.378)

Lunch was served at 12:30 PM. A typical noon meal was essentially vegetarian with fruit and nuts, vegetable soup, lentil chops, baked potatoes, asparagus, lettuce with tomatoes, apple pudding. (Lust, 1912, p.377) The afternoon was patterned upon the morning’s activities. After the noon dinner, people rested, napped until 3 PM, and promptly began their afternoon activities with a half-hour of outdoor games and exercises. Patients then would attend their treatments, which would be followed by the sun and air baths, ending with exercises and games. Before supper, there was always time to swim, row boats, or even to go fishing.

Sun Baths

Strueh, like many of his naturopathic colleagues, believed that skin was influenced by sunlight. He contended, “An inactive skin means sickness; an active skin means health.” (Strueh, 1916, p.433) To aid skin function, in his view, sunlight helped support its eliminative functions, which was as important as the kidneys. Strueh believed wholeheartedly that sun baths were essential for effective curative treatment plans. He proclaims, “Any method of treatment which does not include sun baths is incomplete and mere patch work… A few hours everyday spent in the sun bath, with proper exercise and followed by a cold spray or other water application, have the most wonderful effect upon the patient and bring about results which cannot be obtained in any other way.” (Strueh, 1916, p.433)

Water Treatments

Strueh also incorporated numerous water-cure applications, and acknowledged the scientific progress made in medicine through hydrotherapy. He states, “Today [hydrotherapy] is an established scientific method which is advocated and practiced by every progressive physician and taught in every modern medical school.” (Strueh, 1913, p.393) We must remember that Strueh lived during a golden age of hydrotherapy. With the introduction of Simon Baruch’s seminal work, The Principles and Practice of Hydrotherapy [1898] and followed by John Harvey Kellogg’s Rational Hydrotherapy [1901], the flood gates opened for numerous other hydrotherapy books too, by authors such as George Knapp Abbott, Curan Pope, William H. Dieffenbach, and many others. Strueh continues, “We know that properly applied water treatments regulate or modify the circulation of the blood, deepen the respiration, increase the number of blood cells, assist the elimination of toxins through the kidneys and skin, and in short improve the activity of every organ and cell of the body.” (Strueh, 1913, p.392)

Carl Stueh’s Legacy

The patients visiting the Orchard Beach Sanitarium left revitalized. Strueh notes, “It has always been a great pleasure to me to watch the transformation of the regular summer guests at my sanatorium. They come with pallid and haggard, careworn faces, and when after a few weeks they depart, their features are all sunshine and happiness.” (Strueh, 1908, p.126)

As increasing numbers of Naturopaths in our time come again to these splendid traditions, they choose more traditional naturopathic avenues and modalities. As we reacquaint ourselves with our forebears, we may glean some forgotten therapy to be incorporated into our current practices when we rediscover these all-too-often also-forgotten elders. Dr Carl Strueh championed Nature Cure at a time when these concepts were in their germinal stage. He was a pioneer and dedicated to the principles of Naturopathy, and has left a remarkable legacy for modern naturopathic doctors. His therapeutic tools were simply fresh air, sun baths, exercise, simple diet, and hydrotherapy.

Sussanna Czeranko ND, BBE, incorporates “nature-cure” approaches to primary care by including balneotherapy, breathing therapy, and nutrition into her naturopathic practice. Dr Czeranko is a faculty member working as the Rare Books curator at NCNM and is currently compiling a 12-volume series based upon the journals published early in the last century by Benedict Lust. Four of the books have been published: Origins of Naturopathic Medicine, Philosophy of Naturopathic Medicine, Dietetics of Naturopathic Medicine, and Principles of Naturopathic Medicine. In addition to her work in balneotherapy, she is the founder of the Breathing Academy, a training institute for naturopaths to incorporate a scientific model of breathing therapy called Buteyko into their practice. She is a founding board member of the International Congress of Naturopathic Medicine and a member of the International Society of Medical Hydrology.

Sussanna Czeranko ND, BBE, incorporates “nature-cure” approaches to primary care by including balneotherapy, breathing therapy, and nutrition into her naturopathic practice. Dr Czeranko is a faculty member working as the Rare Books curator at NCNM and is currently compiling a 12-volume series based upon the journals published early in the last century by Benedict Lust. Four of the books have been published: Origins of Naturopathic Medicine, Philosophy of Naturopathic Medicine, Dietetics of Naturopathic Medicine, and Principles of Naturopathic Medicine. In addition to her work in balneotherapy, she is the founder of the Breathing Academy, a training institute for naturopaths to incorporate a scientific model of breathing therapy called Buteyko into their practice. She is a founding board member of the International Congress of Naturopathic Medicine and a member of the International Society of Medical Hydrology.

References:

Lust, B. (1912). The editor’s lecture tour. The Naturopath and Herald of Health, XVII (5), 319-321.

Lust, B. (1912). My visit to Dr. Carl Strueh’s Yungborn, McHenry, Illinois, near Chicago. The Naturopath and Herald of Health, XVII (6), 376-380.

Miller W. H. (1907). Biographical sketches of Chicago’s prominent nature cure physicians. The Naturopath and Herald of Health, VIII (3), 84-86.

Strueh, C. (1908). The need of a vacation. The Naturopath and Herald of Health, IX (4), 125-128.

Strueh, C. (1913). Symptomatic treatment a waste of effort and time. The Naturopath and Herald of Health, XVIII (3), 170-171.

Strueh, C. (1913). Dr. Carl Strueh’s health resort. The Naturopath and Herald of Health, XVIII (6), 389-394.

Strueh, C. (1916). Dr. Carl Strueh’s sanitarium and health resort. Herald of Health and Naturopath, XXI (5), 302-303.

Strueh, C. (1916). Sun baths. Herald of Health and Naturopath, XXI (7), 433.

Strueh, C. (1918). Exercise. Herald of Health and Naturopath, XXIII (1), 65.