Botanical Treatment of Shingles: A Case Report

Vanessa Ferreira, ND

Student Scholarship – 2nd Place Case Study

Herpes zoster, or shingles, is a viral infection caused by the reactivation of the varicella-zoster virus (VZV). This virus, which lays dormant in the dorsal root ganglia after a primary infection of varicella, is most commonly known as chickenpox.1 This virus can theoretically affect 99.5% of people in the United States who have previously been infected with the varicella virus, but most often reactivates in individuals over the age of 40.1 VZV tends to affect the older population, due to immune deterioration and a reduced ability to fight off viral infections. Approximately 1 in 3 people in the United States will develop shingles during his or her lifetime.1

Shingles – Course & Conventional Treatment

Typical untreated healing time of herpes zoster symptoms is approximately 30 days, although many symptoms last weeks, months, or even longer. More severe symptoms often associated with herpes zoster include post-herpetic neuralgia, which leads to persistent stabbing and burning pain for 3 or more months following complete healing of the lesions.2 This pain occurs along the previously shingles-affected dermatome, without the development of a rash.

Conventional medicine most commonly uses antiviral pharmaceuticals (such as oral acyclovir) and narcotic analgesics (such as oxycodone) for treatment of the virus and pain relief, respectively. Acyclovir and related compounds, including valacyclovir and famciclovir, act by competitive inhibition of the viral DNA polymerase, followed by incorporation into and termination of the growing viral DNA chain.

Case Study Using Botanicals

Naturopathic medicine has had repeated success treating VZV with the use of botanicals that have antiviral, anti-inflammatory, analgesic, and vulnerary properties. Historical use of Melissa officinalis,3,4 Hypericum perforatum,5-7 Eleutherococcus senticosus,8 Glycyrrhiza glabra,9,10 Lavandula officinalis,11 and Sarracenia purpurea12-14 suggests antiviral properties of these botanicals, making them putative efficacious herbs for use against VZV. Some of these herbs have other actions as well that may aid in the healing process of herpes zoster infections. Examples include Hypericum perforatum with vulnerary actions, Glycyrrhiza glabra with anti-inflammatory properties, and Sarracenia purpurea with analgesic constituents. Significantly, constituents of Sarracenia purpurea have been used for relieving pain in the neck, back, and other body locations.13,14 Allantoin and glycerin have been shown in studies to have wound-healing properties,15,16 and therefore may improve VZV-associated symptoms as well.17 The following case study demonstrates the efficacy of a commercially available topical formulation, containing the ingredients listed above, in the successful treatment of an active herpes zoster outbreak.

Patient Presentation & History

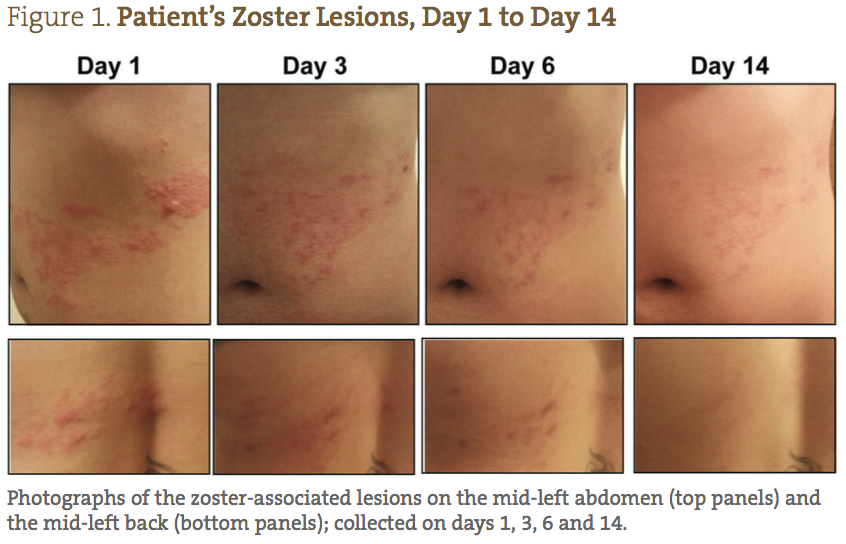

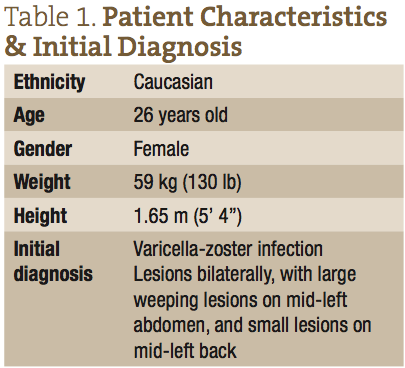

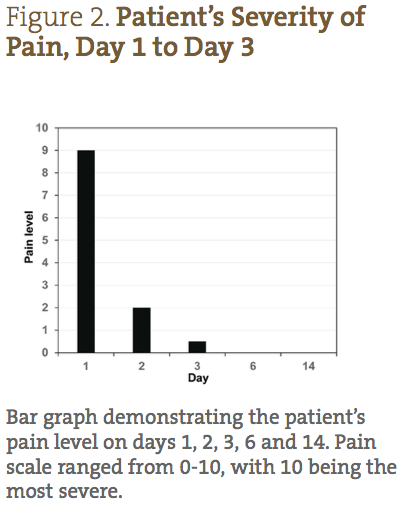

A 26-year-old Caucasian female presented with a diagnosis of herpes zoster, with small lesions on her mid-right abdomen, and large weeping lesions on her mid-left abdomen and back (Figure 1). The patient’s physical characteristics upon intake are shown in Table 1. The patient complained of severe burning, pain, and itching, which she reported prior to treatment as a 9/10 (10 being the worst) (Figure 2). Her primary care physician prescribed acyclovir, gabapentin, and codeine; however, she declined treatment because she was interested in seeking naturopathic alternatives.

Treatment

Following a medical exam, the patient was prescribed a commercially available botanical formulation of ethanol- and/or glycerin-extracted Hypericum perforatum (2.5%), Lavandula officinalis (10%), Glycyrrhiza glabra (2.5%), Melissa officinalis (6%), Eleutherococcus senticosus (4%), and mixed species of Sarracenia (25%) suspended in a proprietary gel (50%). The gel was composed of allantoin, Aloe vera, ammonium acryloyldimethyltaurate, EDTA, and methylchloroisothiazolinone. The patient was asked to document her pain and photograph the affected area to monitor her progress.

Instructions for application of the topical gel were to wash the area with warm water only (no soap) and pat dry, and then, beginning at the outer edge of the affected area, apply a very thin layer of gel to cover all of the lesions. The entire area was then covered with a Teflon-coated bandage. The gel was to be reapplied in the same fashion 4 times daily, and she was to re-wash the area prior to bedtime and again in the morning. The physician recommended no other adjunct medications or supplements during the treatment period.

Outcome

The patient was able to completely follow the recommended protocol and provide reports on days 1, 2, 3, 6, 9 and 14. Figure 1 demonstrates the visual improvement of the herpes zoster lesions on the mid-left abdomen (top panels) and the mid-left back (bottom panels) throughout the protocol; Figure 2 shows the improvements in pain and sensitivity. Dramatically, the greatest improvement in both lesion severity and pain was observed from day 1 to day 3. The lesions started out as extremely painful, large fluid-filled vesicles; by day 3 a significant decrease in fluid extrusion from the blisters was observed, and the vesicles were no longer raised. By day 3 of treatment, the lesions only showed signs of erythema and were beginning to form crusts. In addition, on days 1, 2 and 3, the patient reported her pain level went from 9/10, to 2/10, to less than 1/10, respectively. She also reported that the itching was completely resolved by day 3. Between days 3 and 6, the lesions dried and crusted, and her pain completely resolved. By day 9, all of the lesions were healed, with only minor erythema still visible. By day 14, the patient reported feeling completely well again, with very slight redness where the initial, larger lesions were located.

Discussion

This case demonstrates the effectiveness of a naturopathic approach in the treatment of an outbreak of herpes zoster, using a topical antiviral/analgesic botanical formulation. A typical untreated herpes zoster outbreak frequently requires a minimum of 30 days to fully resolve. In many instances, resolution can take much longer. The common timeline for shingles is a 2 to 3-day prodromal phase, followed by 3-4 days for the rash to form into vesicles or blisters.18 Fluid inside the blisters is initially clear, but may become cloudy after 3-4 days. After another 5 days, the blisters begin erupting, secreting fluid, and subsequently drying out and forming a crust. Complete healing typically takes another 2-4 weeks.2

Oral acyclovir and related compounds are the most common first-line treatment for a herpes zoster outbreak, but these agents have often been proven only moderately effective in clinical settings. A clinical study demonstrated that acyclovir – dosed at 800 mg, 5 times daily for 7-10 days – had no statistically significant effect on acute pain after 1 month.19 Acyclovir was associated with a decrease in overall healing time of herpes zoster when compared to a placebo, but only by 1-2 days. Another study,20 which compared valacyclovir with acyclovir, showed that valacyclovir healed the rash by day 15, with complete healing by day 22. This was better than acyclovir’s healing time of 29 days, but still demonstrated only moderate efficacy.20 As shown in this case study, the botanical herbal formulation used to treat herpes zoster resulted in the fluid-filled vesicles crusting over by day 3, and complete healing by day 14, which is at least a 50% decrease in healing time compared to acyclovir.

Acyclovir, like many pharmaceutical-grade treatments, have common, as well as serious, side effects associated with their use. Acyclovir’s side effects can include a general ill feeling, nausea or vomiting, diarrhea, headaches, and the more concerning side effects of seizures, hallucinations, and possible allergic reactions. Notably, the topical herbal formulation used in this case study presented no adverse reactions when used on the patient during the treatment protocol. This may support the use of these antiviral/analgesic herbs for topical application on immunocompromised patients infected with VZV, who represent one of the largest populations affected by herpes zoster. With acyclovir being so commonly used to treat VZV, it is not surprising that numerous studies illustrate the frequent development of drug-resistant herpes viruses in clinical settings, particularly in immunocompromised patients. When using a mono-therapy like acyclovir, a virus is often more likely to gain resistance, as compared to a combination therapy21,22 such as a multi-herbal formulation, since numerous different constituents are present to inhibit viral replication.

Pain is one of the most debilitating aspects of a herpes zoster outbreak, and with acyclovir and valacyclovir treatments, alone, pain is typically not fully relieved until days 14-29.20 Oxycodone, an oral opioid pain medication, is the most common conventional treatment prescribed for the neuralgia pain associated with a herpes zoster outbreak. However, oxycodone has several adverse side effects, including constipation, nausea, vomiting, headaches, fatigue, and itchiness. Studies with oxycodone report a moderate reduction in pain in only about 50% of shingles patients, and the medication is often discontinued due to severe constipation.23 Therefore, conventional approaches have limited success, at best, in reducing pain in patients afflicted with shingles. In the case presented here, the antiviral/analgesic botanical formulation resulted in a drastic decrease in pain by day 2, and complete pain relief between days 3 and 6. Much of this analgesic effect is likely associated with the Sarracenia spp, which has a long history of pain relief and use as an anesthetic.12

Pain is one of the most debilitating aspects of a herpes zoster outbreak, and with acyclovir and valacyclovir treatments, alone, pain is typically not fully relieved until days 14-29.20 Oxycodone, an oral opioid pain medication, is the most common conventional treatment prescribed for the neuralgia pain associated with a herpes zoster outbreak. However, oxycodone has several adverse side effects, including constipation, nausea, vomiting, headaches, fatigue, and itchiness. Studies with oxycodone report a moderate reduction in pain in only about 50% of shingles patients, and the medication is often discontinued due to severe constipation.23 Therefore, conventional approaches have limited success, at best, in reducing pain in patients afflicted with shingles. In the case presented here, the antiviral/analgesic botanical formulation resulted in a drastic decrease in pain by day 2, and complete pain relief between days 3 and 6. Much of this analgesic effect is likely associated with the Sarracenia spp, which has a long history of pain relief and use as an anesthetic.12

This case study used research-based, historical anti-viral/analgesic botanical herbs in the efficacious treatment of a herpes zoster outbreak in a clinical setting. It demonstrates significant efficacy related to overall healing of lesions and a rapid decrease in pain when compared to a conventional first-line therapy such as acyclovir. This case study provides support that an alternative botanical protocol may represent a more efficacious treatment of shingles caused by the varicella-zoster virus.

Author Affiliations:

Bertram L. Jacobs, PhD2

Karen Denzler, PhD2

Robert Waters, PhD2

Richard Chamberlain, MD3

Kenneth J. Proefrock, NMD4

Jeffrey O. Langland, PhD1,2

1Southwest College of Naturopathic Medicine, Tempe, AZ 85282; 2Arizona State University, Biodesign Institute, Tempe, AZ 85287; 3Precision Surgical, LLC, Scottsdale, AZ 85260; 4Total Wellness Medical Center/Vital Force Naturopathic Compounding, Surprise, AZ 85374

Vanessa Ferreira, ND, is a naturopathic physician from SCNM, where she completed this case study as a student. During her naturopathic education, Dr Ferreira focused her time on Global Health, Women’s Health, and Homeopathy. In addition, she has extensive experience as a teaching and research assistant at SCNM. Her main research project – on inhibiting Candida growth and differentiation with the use of botanicals – was showcased at the AANP in 2014. Dr Ferreira has worked in the Biodesign Institute at Arizona State University, doing research on botanicals and herpes viruses. She looks forward to providing more case-based research to support the efficacy of modalities used in naturopathic medicine in the future.

Vanessa Ferreira, ND, is a naturopathic physician from SCNM, where she completed this case study as a student. During her naturopathic education, Dr Ferreira focused her time on Global Health, Women’s Health, and Homeopathy. In addition, she has extensive experience as a teaching and research assistant at SCNM. Her main research project – on inhibiting Candida growth and differentiation with the use of botanicals – was showcased at the AANP in 2014. Dr Ferreira has worked in the Biodesign Institute at Arizona State University, doing research on botanicals and herpes viruses. She looks forward to providing more case-based research to support the efficacy of modalities used in naturopathic medicine in the future.

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Shingles (Herpes Zoster). Last updated November 25, 2014. CDC Web site. http://www.cdc.gov/shingles/hcp/clinical-overview.html. Accessed December 1, 2014.

Janniger CK. Herpes Zoster Clinical Presentation. Updated May 27, 2014. Medscape Web site. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1132465-clinical#aw2aab6b3b3. Accessed December 1, 2014.

Astani A, Navid MH, Schnitzler P. Attachment and penetration of acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex virus are inhibited by Melissa officinalis extract. Phytother Res. 2014;28(10):1547-1552.

Astani A, Reichling J, Schnitzler P. Melissa officinalis extract inhibits attachment of herpes simplex virus in vitro. Chemotherapy. 2012;58(1):70-77.

Clewell A, Barnes M, Endres JR, et al. Efficacy and tolerability assessment of a topical formulation containing copper sulfate and hypericum perforatum on patients with herpes skin lesions: a comparative, randomized controlled trial. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11(2):209-215.

Taylor RS, Manandhar NP, Hudson JB, Towers GH. Antiviral activities of Nepalese medicinal plants. J Ethnopharmacol. 1996;52(3):157-163.

Wölfle U, Seelinger G, Schempp CM. Topical application of St. John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum). Planta Med. 2014;80(2-3):109-120.

University of Maryland Medical Center. Herpes simplex virus. Last reviewed August 21, 2013. UMM Web site. http://umm.edu/health/medical/altmed/condition/herpes-simplex-virus. Accessed December 1, 2014.

Fiore C, Eisenhut M, Krausse R, et al. Antiviral effects of Glycyrrhiza species. Phytother Res. 2008;22(2):141-148.

Pompei R, Flore O, Marccialis MA, et al. Glycyrrhizic acid inhibits virus growth and inactivates virus particles. Nature. 1979;281(5733):689-690.

Altaei T, Ahmed SA. Topical treatment of herpes simplex lesion by lavender cream. J Bagh College Dentistry. 2012;24(1):70-76. Available at: http://www.iasj.net/iasj?func=fulltext&aId=70197. Accessed December 1, 2014.

Arndt W, Mitnik C, Denzler KL, et al. In vitro characterization of a nineteenth-century therapy for smallpox. PLoS One. 2012;7(3):e32610.

Sarapin. DynamicPainRehab Web site. http://www.dynamicpainrehab.com/uploads/SARAPIN.pdf. Accessed December 1, 2014.

Manchikanti KN, Pampati V, Damron KS, McManus CD. A double-blind, controlled evaluation of the value of sarapin in neural blockade. Pain Physician. 2004;7(1):59-62.

Ozçelik B, Kartal M, Orhan I. Cytotoxicity, antiviral and antimicrobial activities of alkaloids, flavonoids, and phenolic acids. Pharm Biol. 2011;49(4):396-402.

Atrux-Tallau N, Romagny C, Padois K, et al. Effects of glycerol on human skin damaged by acute sodium lauryl sulphate treatment. Arch Dermatol Res. 2010;302(6):435-441.

Food & Drug Administration. OTC Active Ingredients. April 7, 2010. FDA Web site. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/AboutFDA/CentersOffices/CDER/UCM135688.pdf. Accessed December 1, 2014.

Dworkin RH, Johnson RW, Breuer J, et al. Recommendations for the management of herpes zoster. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44 Suppl 1:S1-S26.

Opstelten W, Eekhof J, Neven AK, Verheij T. Treatment of herpes zoster. Can Fam Physician. 2008;54(3):373-377.

Raju GN, Raza M, Kumar TN, Singh G. Comparative study of the efficacy of valacyclovir and acyclovir in herpes zoster. Int J Pharm Biomed Res. 2011;2(2):119-123.

Andrei G, Fiten P, De Clercq E, et al. Monitoring drug resistance for herpesviruses. Methods Mol Med. 2000;24:151-169.

Gilbert C, Bestman-Smith J, Boivin G. Resistance of herpesviruses to antiviral drugs: clinical impacts and molecular mechanisms. Drug Resist Updat. 2002;5(2):88-114.

Dworkin RH, Barbano RL, Tyring SK, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of oxycodone and of gabapentin for acute pain in herpes zoster. Pain. 2009;142(3):209-217.