Daivati Bharadvaj, ND

What is Chronic Fatigue Syndrome?

Fatigue remains one of the most common reasons that people seek medical attention. Chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) represents just one of many causes of fatigue. It is a debilitating long-term illness that often dramatically impacts the person’s way of life. What used to be pigeonholed as the “yuppie flu” is now found to affect at least 2 million Americans, regardless of age, gender, ethnicity or socioeconomic group (Bierl et al., 2004). Even these estimates are largely conservative since so many people suffering from CFS are ignored and told “it’s all in your head.”

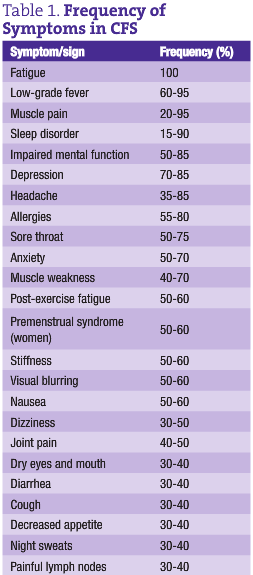

But it’s not all in the head. People dealing with CFS have been suffering from fatigue that cannot be explained by any other disease for at least six months. (See the accompanying list of excluding conditions.) The fatigue is unremitting – patients do not feel better despite adequate rest. Oftentimes, the fatigue is just one of a cluster of signs and symptoms. Most people with CFS also suffer from low-grade fever, sore throat, enlarged lymph nodes, myalgia and malaise, headaches, migratory joint pains, neurological symptoms and sleep disturbance. (See Table 1 for the frequency of these signs and symptoms.) So far, there are no “official” diagnostic tests except for this case definition. And, large review articles have concluded that standard pharmaceutical medications are ineffective, “failing to demonstrate clinical benefit” (Lloyd et al., 1993).

As NDs, we are more likely to attract people with this condition, and given our philosophy and natural medicine toolbox, we are also well equipped to offer hope and recovery to them. Towards that end, our first step is to understand the etiologies and origins behind this complex illness.

Immune Dysfunction in CFS

Researchers have yet to isolate a single causative agent for CFS. In fact, CFS is a true example of a multifactorial disease. Factors involved in the pathogenesis fall into one of several categories: immune system dysfunction, viruses, allergies and food intolerances, oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction, stress and adrenal fatigue. Many additional theories exist, but these origins have the most research to back them. Let us review the nature of immune dysfunction in CFS.

What used to be known as an immune deficiency syndrome is now better understood to be more of an immune dysfunction. While activity of some immune cells may be significantly reduced, many others are excessively stimulated.

- NK cells: People with CFS tend to have lower numbers of NK cells as well as markedly reduced activity (Zhang et al., 1999; Gupta and Vayuvegula, 1991; Barker et al., 1994). There are three main theories behind this issue: 1) an impairment in L-arginine mediation of NK cells can lead to poor functioning (Ogawa, 1998); 2) toxic overload (in the form of environmental chemicals such as organochloropesticides) can also deplete NK cells and render them less potent; and 3) the NK cells in people with CFS fail to adequately produce enough perforins, chemicals released from cytotoxic immune cells that lyse the cell membranes of pathogenic cells (Maher et al., 2005). Without perforins, NK cells become less useful in defense against foreign attack.

- T cells: Higher populations of CD4 and CD8 T cells are found in people with CFS. Also, the proportions between them are different compared to healthy individuals. However, like NK cells, the cytotoxic capability of CD8 cells is diminished due to decreased perforin synthesis (Maher et al., 2005).

- B cells: Increased circulating levels of B cells are more likely in CFS, corresponding with increased intracellular adhesion molecules on monocytes (Tirelli et al., 1994). Perhaps the body’s way of compensating for a drop in cytotoxicity from NK cells and CD8 T cells is to turn out more B cells, CD4 T cells and monocytes to recruit other aspects of our immune defenses.

- Cytokines: Several studies have found elevated levels of interleukins, interferons and other cytokines (Linde et al., 1992; Cohen and Powderly, 2004). These patterns of higher levels are very similar to those seen in chronic viral infections such as influenza, infectious mononucleosis and parvovirus.

According to one group of scientists, “60% of the 70 CFS individuals studied had elevation of at least one immune mediator” (Patarca, 1994). The trend for people with CFS is to have excessive immune activation in general, with lowered NK cell numbers and cytotoxic potential. This is similar to the patterns seen in chronic viral illnesses. As NDs, our comprehension of this “polycellular activation model” will help us better serve our CFS patients. In patients with varying degrees of chronic fatigue, we need to address their likely immune dysfunction cautiously by modulating the overall immune response, not just blindly bolstering it. We need to carefully select treatment options that support NK cell production and cytotoxic power, while reducing the excessive T and B cell and cytokine response. And we would benefit to look at possible viral origins for this immune dysfunction. As part of our philosophy of tracing back to the root cause and treating each individual uniquely, we are in an ideal position for addressing the complex immune issues around CFS.

According to one group of scientists, “60% of the 70 CFS individuals studied had elevation of at least one immune mediator” (Patarca, 1994). The trend for people with CFS is to have excessive immune activation in general, with lowered NK cell numbers and cytotoxic potential. This is similar to the patterns seen in chronic viral illnesses. As NDs, our comprehension of this “polycellular activation model” will help us better serve our CFS patients. In patients with varying degrees of chronic fatigue, we need to address their likely immune dysfunction cautiously by modulating the overall immune response, not just blindly bolstering it. We need to carefully select treatment options that support NK cell production and cytotoxic power, while reducing the excessive T and B cell and cytokine response. And we would benefit to look at possible viral origins for this immune dysfunction. As part of our philosophy of tracing back to the root cause and treating each individual uniquely, we are in an ideal position for addressing the complex immune issues around CFS.

Conditions that Exclude the Diagnosis of CFS

- Any active medical condition that may explain the presence of chronic fatigue

- Any previously diagnosed medical condition without resolution documented beyond reasonable clinical doubt, and for which continued activity may explain the chronic fatiguing illness

- Any past or current diagnosis of major depression with melancholic or psychotic features, bipolar affective disorder, schizophrenia of any subtype, delusional disorders of any subtype, dementias of any type, anorexia nervosa or bulimia

- Alcohol or other substance abuse within two years before the onset of the chronic fatigue and any time afterwards

- Severe obesity as defined by a body mass index (BMI) ≥45

- Any unexplained physical examination finding or laboratory or imaging test abnormality that strongly suggests the presence of an exclusionary condition

Source: The Chronic Fatigue And Immune Dysfunction Syndrome (CFIDS) Association of America

Daivati Bharadvaj, ND is a naturopathic physician in private practice at Alive & Well Healing Arts in Portland. She is a graduate of NCNM, where she completed her residency in family practice medicine. Her undergraduate degree in nutritional sciences was earned at Cornell University’s college of human ecology. Dr. Bharadvaj is the recent author of a resource for CFS sufferers and medical providers, called Natural Treatments for Chronic Fatigue Syndrome.

Daivati Bharadvaj, ND is a naturopathic physician in private practice at Alive & Well Healing Arts in Portland. She is a graduate of NCNM, where she completed her residency in family practice medicine. Her undergraduate degree in nutritional sciences was earned at Cornell University’s college of human ecology. Dr. Bharadvaj is the recent author of a resource for CFS sufferers and medical providers, called Natural Treatments for Chronic Fatigue Syndrome.

References

Bierl C et al: Regional distribution of fatiguing illnesses in the United States: a pilot study, Popul Health Metr Feb 4;2(1):1, 2004.

Lloyd AR et al: Immunologic and psychologic therapy for patients with chronic fatigue syndrome: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, Am J Med Feb;94(2):197-203, 1993.

Zhang Q et al: Changes in immune parameters seen in Gulf War veterans but not in civilians with chronic fatigue syndrome, Clin Diagn Lab Immunol Jan;6(1):6-13, 1999.

Gupta S and Vayuvegula B: A comprehensive immunological analysis in chronic fatigue syndrome, Scand J Immunol Mar;33(3):319-27, 1991.

Barker E et al: Immunologic abnormalities associated with chronic fatigue syndrome, Clin Infect Dis Jan;18 Suppl 1:S136-41, 1994.

Ogawa M et al: Decreased nitric oxide-mediated natural killer cell activation in chronic fatigue syndrome, Eur J Clin Invest Nov;28(11):937-943, 1998.

Maher KJ et al: Chronic fatigue syndrome is associated with diminished intracellular perforin, Clin Exp Immunol Dec;142(3):505-511, 2005.

Tirelli U et al: Immunological abnormalities in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome, Scand J Immunol Dec;40(6):601-8, 1994.

Linde A et al: Serum levels of lymphokines and soluble cellular receptors in primary Epstein-Barr virus infection and in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome, J Infect Dis Jun;165(6):994-1000, 1992.

Cohen J, Powderly WG: Infectious Diseases (2nd ed). Philadelphia, PA: Mosby/Elsevier; 2004.

Patarca R et al: Dysregulated expression of tumor necrosis factor in chronic fatigue syndrome: interrelations with cellular sources and patterns of soluble immune mediator expression, Clin Infect Dis Jan;18 Suppl 1:S147-53, 1994.