David J. Schleich, PhD

The kernel of the issue is that academic governance and corporate governance are not the same. They share similar processes but live in different valleys. CNME oversight of standards is a form of governance, although it is at arm’s length. Its commissioners are volunteers, though, just as are the directors, trustees, or governors of our institutions. Added to the challenge is that the programmatic accreditation (a form of governance) of naturopathic education is a check-in after the fact. Institutional governance is more on-the-spot, and grounded in the fulfillment of strategic plans. The notions of advancement and development, for example, wrinkles brows among academic accreditation professionals. And, compounding the cooking stew of oversight is a model of governance at our naturopathic colleges where naturopathic doctors are not the major players on the boards of the non-profit organizations which house our programs. For a long time now, in fact, NDs are in a minority on boards where ND programs are functioning. In the interest of strengthening the cumulative skills of trustees to monitor and plan for all the dimensions of a post-secondary/post-graduate/higher education environment, a natural migration to multi-discipline/profession boards has been the norm for decades.

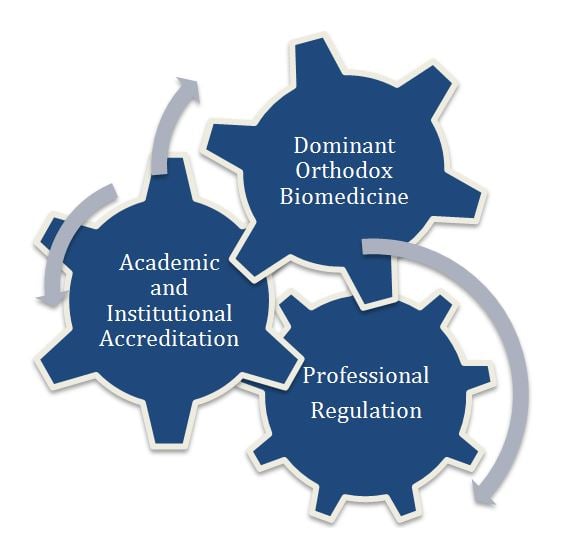

This is not only a compositional fact, but also a numerical fact. Today, a coherent vision of what governance means for naturopathic medical education requires us to separate out several factors all grinding around each other: the long-time dominance of orthodox biomedicine; the urgency and safe harbors of professional regulation; and academic and institutional accreditation with its helpful standards and benchmarks (Figure 1). Our ultimate goal is professional formation, even though our institutions parse the outcome into statements about producing graduates who will be appropriately skilled and highly motivated to build the profession in largely unfriendly terrain.

Orthodox biomedicine holds all the high ground in that landscape, and has played by the rules of professional formation quite effectively, especially since Flexner’s 1910 report. Orthodox medicine members control most of the turnstiles (the residency match, for example, in the United States; hospital privileges; lucrative insurance codes). Heterodox naturopathic medicine, on the other hand, despite having at long last learned the rules, at the same time has to find safe harbor in the healthcare landscape. At the same time as we grapple with academic and institutional accreditation for the training programs which nourish the profession with new participants, we wrestle with civil authorities for beachheads in a regulated, economic marketplace which is only now beginning to understand where we can significantly contribute. The business and regulatory environment where all this happens is busy, complex, and unforgiving.

In the middle of all this fuss and rattle, there is a persistent confusion about the boundaries of academic governance and institutional governance. This blurring occurs because our governance skills are collectively a bit threadbare when it comes to aiming directly at achieving equal access in healthcare design and delivery. Regrettably, not once have the governors, trustees, or directors of colleges, or universities where naturopathic programs are housed, been able to come together from across our network of 8 programs. Lots of people who work for our institutions gather on a regular basis (AANMC, NCC, national, state, and regional associations), but not our trustees. There are NDs on the boards of the 4 universities and 4 colleges where CNME-accredited naturopathic programs are operating, of course, who join such meetings; however, there are more laypersons than experienced NDs, the former of which have not benefitted from such experiences. The distribution of trustee membership is not surprising, given how strongly affected our efforts are by the social and political determinants we all live in, all the time. We live in concentric spheres of influence: higher education, health care, non-profit, and in America, at least, the post-ACA health economy.

Overlapping Roles

Stirring this almost boiling pot even more are the overlaps of the roles of regulatory boards, volunteer medical associations, and legal regulatory bodies.

Naturopathic Profession Regulatory Boards

- Public protection through legislation, regulations, investigations, disciplining registrants

- Liaison with state/provincial legislatures

- Interpretation of regulations

- Appointed by government

Naturopathic Volunteer State and National Medical Associations

- Public advocacy for the naturopathic professional community

- Consumer and public education about naturopathic medicine

- Promotion of the profession with the public, business

- Elected by the professional membership

School-based Board(s) of Directors/Trustees/Governors

- Articulation of the mission and vision of the institution in which the ND program operates

- Oversight of academic freedom and intellectual diversity

- Setting of educational strategy

- Review of transparent performance and results data, including evidence of student learning

- Oversight of higher education compliance

- Fiduciary and financial oversight and accountability

- Hiring and firing of presidents

- Development of board human resources

With respect to higher education, we have become codependent in many ways, most particularly in North America. In many American states, for example, extensive authority has been delegated to lay boards, both in the public and the private sectors, either by government or internally by the self-perpetuating boards of non-profit, private institutions. Our naturopathic colleges are part of that scenario. The result has been that most academic and internal resource allocations are predicated on institutional prerogatives first, and professional formation priorities, second. This is also not surprising, given that we have to hold our spot in the mainstream of medical education and regulation if the profession is to endure and to grow.

Complicated Questions in Naturopathic Education Governance

There are many complicated questions jabbing at this mosaic of naturopathic education governance. We could begin by asking: what is the content of what needs to be learned for success in the widely varying scopes our graduates encounter? Or, given the rapid intrusion of integrative medicine into the marketplace, we might ask: which way should we lean? The answers to these questions are being determined less by the profession and more by our hard-working lay volunteer trustees who often have not benefitted from immersion in the history, philosophy, and social determinants of naturopathic professional formation. We have not served our trustees well in that regard.

As a case in point, should we align our scarce resources toward the profession, the institution, or the market? Should we insulate our programs – as many public colleges have done until recently – as much as possible from both state regulation and market influences, and focus consistently on our mission of developing the profession in North America instead? Or, shall we cozy up to the mainstream to make headway? Another question is, to what extent can we sell our programs within the increasingly competitive landscape of “integrative medicine,” especially when cherry-picking biomedicine entrepreneurs are eagerly establishing their fashionable practices and new board certifications in holistic and integrative medicine in the same neighborhoods as our very own graduates?

When I think of what we’re living through these days, I’m reminded of the heady 60s and Theodore Roszak’s The Making of a Counterculture, published at the end of that transformative decade. His deliberations echoed the popular thinking of Herbert Marcuse, Normon O. Brown, Allen Ginsberg, Paul Goodman, and others. In the parlance of the book, naturopathic medicine constitutes a subculture, a heterodox medical system subculture, in fact. Roszak’s insights are singularly important and worth a look, even a half-century later. His contention was that ours is a technocratic society in which “those who govern justify themselves by appeals to technical experts who, in turn, justify themselves by appeal to scientific forms of knowledge.” (Roszak, 1969, p.158).

In models whose various boundaries are increasingly blurring, our medicine, then, is a subculture within a larger, dominant culture of the system of many names: allopathic medicine, biomedicine, scientific medicine. That larger culture historically and perhaps inevitably always defaults to assimilating everything in its path. It will take what it wants from the smaller group, most particularly if what is co-opted is of value in the marketplace. Good academic and institutional governance of the educational purposes and practicalities of naturopathic education can help strengthen the naturopathic medical system in the face of these pressures. However, that governance structure continues to be increasingly blurred in the face of health regulation, dominant allopathic market control, and academic accreditation processes. The stew of higher education policy and resource allocation, professional practice, regulatory and public policy frameworks, and the unrelenting drive of biomedicine to dominate the health care terrain, simmers near a boil all the time.

In the prescient article, “Good Governance: The Inflation of an Idea,” Merilee Grindle, of the Harvard Kennedy school, hits the nail on the head when confronting this dilemma. While we all concur that good governance is a noble and essential idea, Grindle digs deeply to find out where good governance is actually happening, and even more deeply into what’s missing in that good governance when it is discovered. Among numerous valuable ideas, she explains that good governance “calls needed attention to the institutional underpinnings of effective economic and political management” (Grindle, 2010) – a fine place to focus for naturopathic medicine educators who have annual budgets to manage and whose accreditors keep asking for 3-year pro formas, and whose state licensing boards insist on differentiated professional practice outcomes to match the regulations in place. Grindle’s reports on what the scholarly literature has to say about the concept of good governance is worth a look. Ideally, she says, it should make available to institutions “fair, judicious, transparent, accountable, participatory, responsive, well-managed, and efficient” policies, procedures, and practices. In the post-ACA universe, that availability is uneven. (Grindle, 2010)

The Special Place of Translational Research in Good Governance

There is another pinch point where governance oversight encounters uneven terrain, and that is in the realm of translational research. This aspect of naturopathic medical education (academic medicine) is quickly catching up to teaching in importance, and both new and long-serving naturopathic professors already know that they must publish if they are to sustain a commitment to academic naturopathic medicine careers. This important metric for judging the effectiveness of how we support our faculty needs to be included alongside teaching, caring for patients, and savvy about broader political and regulatory matters affecting the profession and the long-term wellness of our programs. It is somewhat infrequent for trustees to have significant knowledge about these dimensions of graduate medical education in our sector. Naturopathic education leaders and many alumni/ae worry especially that the narrow gaze on only biological content at the expense of the larger needs of whole-person patient care will increasingly compromise decisions about educational priorities as the seductive pressure of integrative medicine increases.

Drilling down more specifically into this segment of oversight, experienced naturopathic administrators, themselves, rarely given to research careers, know well that medical research, including naturopathic research, is prone to being increasingly molecular in orientation, at the same time as the profession and many of our students continue to yearn for traditional naturopathy. The need for well equipped labs where substantial scientific projects occur can, even inadvertently, be at odds with funding plans, for example, for a well equipped botanical lab where tincturing and compounding happen. Another long-term impact of this kind of potential dichotomy is that even the emerging, bright generation of naturopathic medical researchers do not easily get to bring naturopathic clinical knowledge and experience to their teaching in an era where evidence-based medicine is very attractive and the turnkey for an academic medicine career. The integration of investigation, in this regard, more than ever needs to be aligned with teaching and patient care. Which segment of the various levels of governance in our world is paying attention to this tension?

It is a tension which accompanies concern that our schools are more caught these days by the tug between licensing boards who have 1 eye on regulated scope and the other eye on a shifting philosophy. Some academic leaders and trustees are already alarmed that the naturopathic profession may go the way of the osteopathic profession in America. There is the fear that the mainstream medical culture, in which too many medical academics consider the practice of medicine to be secondary, will soon be a fear hammering at the gates of the naturopathic city. A concomitant concern is that it will be increasingly difficult going forward to recruit clinicians from busy naturopathic practices to prepare our students for the competitive marketplace of primary care. This circumstance is accompanied in turn by an angst about linking modern biomedical science with naturopathic practice. For teaching in our colleges to be a viable career path, clinicians with an academic inclination look to good governance to protect their heritage and their future all at the same time.

Yet another area which wobbly governance can impact is the sad dearth of dialogue among trustees about cultural and philosophical inquiry in the face of so many contrary imperatives and conflicting priorities in the marketplace. The governance of degree programs (both didactic and clinical) and the governance of residency education are there in the agendas of board meetings, but distorted often in translating fiduciary pressures into decisions which keep the traditional principles of the profession protected.

Governments Worry About Governance Too

These considerations do not occur in isolation. The frequency of withering admonitions from government about the conduct and performance of higher education has the attention of our trustees. The issue scurries around a wrinkled menu of cost, standards, outcomes, and need. There are worries about the burden of student debt, political correctness and intolerance, improper skimming of student loan systems, and unfair allocations by governments and foundations, to name a few.

At the center of this cooking pot is the matter of how higher-education governance is structured, and how this structure finds its way into our schools. Many naturopathic educators contend that the mostly-lay governance of our programs is imbalanced. They point to a skewing of the role, arising from the inclination of directors, trustees, and governors to be mostly donors, advocates, and passive fiduciaries, translating their oversight to college staff, and allowing that oversight to be disproportionately affected by accreditation bodies, naturopathic licensing bodies, and by the sheer complexity of operational realities in naturopathic programs living more and more within multi-program institutions. In the small universities, naturopathic program governance is influenced by lay directors who are not definitively oriented to the professional formation aspirations. Trustees may not understand the larger implications of professional formation, especially the intersection of healthcare terrain regulation, higher education regulation, and inter-professional rivalries. In such a universe of discourse, trustees will need to bring a renewed and vigorous commitment to learning about and understanding not only the academic enterprise (Schmidt, 2014), but also the heterodox place of naturopathic medical education within it. They may wish, going forward, to require for themselves professional development, continuing education, and accountability – a very tall, and somewhat unfair order. Already our boards have much to contend with. They are charged with articulating the mission of the institution in which the naturopathic program operates. They must keep an eye on academic freedom and intellectual diversity. They have to set educational strategy. They look to transparency in performance and results, including evidence of student learning. They hire and fire presidents.

As fiduciaries, trustees act on data. So, as we feed up charts and Powerpoints, and choreograph show-and-tell presentations, it’s up to us to provide more information and insight into these intersecting factors of the hegemony of orthodox medicine, the very complicated role of institutional and programmatic accreditation and the urgencies of professional formation. What our trustees need are succinct dashboards of measures such as graduation rates by demographic, including students who transfer; tuition rates; administrative versus instructional spending; and building utilization (both classrooms and laboratories) by time and day of the week. This kind of data avalanche, though, if not grounded in a deeper, more abiding understanding of professional formation, can backfire. The stew risks boiling over with concerns about capital, statements of cash flow and bank covenants, and whether we watch the pot endlessly or not.

David J. Schleich, PhD, is president and CEO of NCNM, former president of Truestar Health, and former CEO and president of CCNM, where he served from 1996 to 2003. Previous posts have included appointments as vice president academic of Niagara College, and administrative and teaching positions at St. Lawrence College, Swinburne University (Australia) and the University of Alberta. His academic credentials have been earned from the University of Western Ontario (BA), the University of Alberta (MA), Queen’s University (BEd), and the University of Toronto (PhD).

David J. Schleich, PhD, is president and CEO of NCNM, former president of Truestar Health, and former CEO and president of CCNM, where he served from 1996 to 2003. Previous posts have included appointments as vice president academic of Niagara College, and administrative and teaching positions at St. Lawrence College, Swinburne University (Australia) and the University of Alberta. His academic credentials have been earned from the University of Western Ontario (BA), the University of Alberta (MA), Queen’s University (BEd), and the University of Toronto (PhD).

References

Roszak, T. (1969). The Making of a Counter Culture: Reflections on the Technocratic Society and Its Youthful Opposition. New York, NY: Doubleday Books.

Grindle, M. (June, 2010). Good Governance: The Inflation of an Idea. Harvard Kennedy School Faculty Research Working Paper Series. John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University. Available at: http://tinyurl.com/zxlujdw. Accessed November 2, 2015.

Schmidt, B. C. (August, 2014) Governance for a New Era: A Blueprint for Higher Education Trustees. American Council of Trustees and Alumni, Washington, D. C. Available at: https://www.goacta.org/images/download/governance_for_a_new_era.pdf. Accessed November 2, 2015.