Sussanna Czeranko, ND, BBE

Therefore the warm foot bath with ashes and salt is never to be followed by a cold one.

Sebastian Kneipp, 1901, p.183

[Alternate] foot baths are excellent for cold feet, but are also used with other applications, in cases of lung or heart troubles and many other chronic diseases.

Benedict Lust, 1904, p.62

Parents who wish to have healthy children should train them from the very day of their birth to a rational way of living, and to harden their bodies, especially their feet.

Benedict Lust, 1905, p.169

The title of this month’s article comes to us from Khalil Gibran, who reminds us that the role of our feet is to connect us to the earth. Mother Earth and our bare feet are not always top of mind, and they need to be. In this month’s article, let us explore the many different treatments that the early Naturopaths used involving feet. During this journey, we will discover that the feet aren’t just body parts to be adorned by fancy footwear, but are a path for caring for our patients. Feet are essential for us to stand, walk, dance, run, cycle, ski, and engage in the myriad activities that move us about on the earth. Feet tend to be neglected, and it is not until we injure them in some way that we really realize their essential role in our lives. Each month I am able to share articles on topics found in the Benedict Lust’s publications, hoping that the subject resonates with other naturopathic doctors. This month, we are shining some light on our feet.

“Congestion at the centers is the rule in chronic ailments, frigid hands and feet invariably accompanying digestive and circulatory derangement.” (Lust, 1904, p.6) This observation made by Benedict Lust, that cold extremities accompany chronic diseases, can be useful in our assessments and treatments. Lust contributed numerous articles on the subject of treatment and water therapies while formulating many lists of rules and guidelines to help his colleagues master clinical practice. One such clinical pearl was the following: “Always begin with the extremities.” (Lust, 1904, p.6) The foot bath was a small intervention with a multitude of applications for both acute and chronic diseases. For instance, Joseph Hoegen claims, “The foot bath is frequently used as a means of causing diaphoresis in colds, attacks of acute diseases, and also to draw blood from the head and internal organs.” (Hoegen, 1917, p.314) Hoegen continues, “[The foot bath] is a powerful auxiliary in the treatment of those chronic diseases in which inflammation, congestion, and a feeble circulation are prominent symptoms.” (Hoegen, 1917, p.314) The early Naturopaths witnessed hydrotherapy applied to the feet as a safe treatment “leaving no harmful after-effects, provided the treatment is applied in the proper manner.” (Hoegen, 1917, p.311) Let’s explore the different treatments used a century and more ago for the feet.

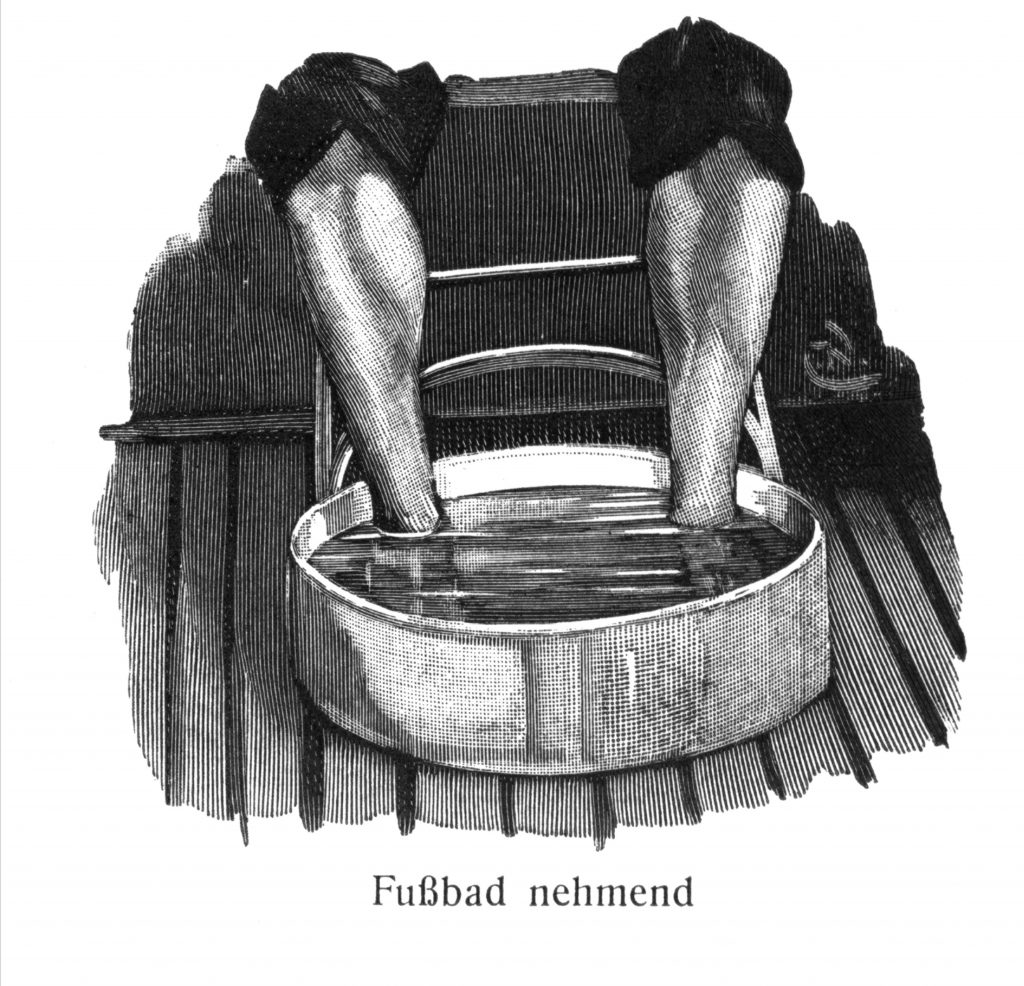

The Cold Foot Bath

The cold foot bath was an excellent means of harmonizing blood flow in chronic diseases, reducing fatigue after a hard day’s work, and helping those with sleep disorders. Sebastian Kneipp cites the benefits of the cold foot bath: “This bath takes away weariness, and brings rest and good sleep.” (Kneipp, 1901, p.183) Lust also found that cold “foot baths were beneficial to all sick people, old and young, and especially children.” (Lust, 1909, p.371)

Kneipp noted, “The cold foot bath serves principally for leading the blood down from the head and chest.” (Kneipp, 1901, p.183) A cold foot bath “consisted of standing in cold water as far as the calves of the legs or higher for one to three minutes.” (Kneipp, 1901, p.183) One important point to keep in mind, though, when considering a cold foot bath, for frail and nervous patients who are chilled and possess cold feet, is proper preparation. Lust advises, “Such patients should be prepared for this kind of cure by cold, wet massage frictions, before they are in a position to take real cold foot baths or to walk barefooted on a wet, cool lawn.” (Lust, 1909, p.370)

Joseph Hoegen recommended, “The cold foot bath is given from 45° to 55° F / 7° to 13° C, and from one to five minutes duration.” (Hoegen, 1914, p.314) This length of time may seem insignificant, but let me suggest that cold water can seem unbearable to even the hardiest feet. Begin with tolerable temperatures and gradually, as your feet harden or become more tolerant of the cold, you will be able to endure colder temperature. Hoegen suggested applying friction or rubbing the feet together. (Hoegen, 1914, p.314) The amount of water in this cold foot bath was 3 to 4 inches of water.

The Warm Foot Bath

Warm foot baths came in many different versions combining different herbal decoctions. Warm water was never used on its own in the warm foot bath. Kneipp adamantly emphasized the point: “Foot baths with warm water only, without anything being mixed with it, I never take or prescribe.” (Kneipp, 1901, p.184) The principle adjuvants that Kneipp used included salt mixed with wood ashes, his beloved hay flowers, and oat straw. The temperature of the warm water used in each of the following baths ranged from 88° to 90° F / 31° to 32° C. (Kneipp, 1901, p.183) These warm baths were well suited for weak and chilled patients who could not tolerate the brutally cold temperatures normally prescribed by Kneipp.

Salt and Wood Ash

The salt and wood ash foot bath was very specific for drawing blood to the feet. The wood ash that Kneipp is referring to is simply the ash from a wood stove or hearth. (Kneipp, 1891, p.81) Salt and wood ash foot baths were calming and indicated for “weak, nervous people, for those who have poor blood, for very young, and very old people, mostly for women, and are effective against all disturbances in the circulation of the blood, against congestions, complaints of the head or neck, cramps, etc.” (Kneipp, 1901, p.183) This bath was very effective in moving blood to the feet, but was not indicated for those who suffered from perspiring feet.

The instructions to implement this bath required “a handful of salt and twice as much wood ashes [that] are mixed in warm water 88° to 90° F / 31° to 32° C. The foot bath is taken for 12 to 15 minutes.” (Kneipp, 1901, p.183)

Hay Flower Foot Bath

Hay flowers were one of the herbal remedies that Kneipp left behind for use in many different disease conditions. Hay flowers were the remains of a hay stack that included “stalks, leaves, blossoms and seeds, which we find in every barn where hay is stored.” (Lust, 1900, p.28) Lust provides instructions on the preparation of the hay flower decoction. “To prepare the decoction, take from three to five handfuls of hay flowers, pour boiling water over them, cover the vessel and let the whole mixture cool to the warmth of 88° to 90° F / 31° to 32° C.” (Lust, 1900, p.28) The decoction can be strained before using in the foot bath; however, Kneipp indicated that there was no difference if the hay flowers remained.

Hay flower foot baths are especially useful for dissolving, evacuating and strengthening. Kneipp cites several indications for use: “[Hay flower foot baths] are of good service for diseased feet, especially sweating feet, open wounds, contusions, [bruising], tumors, gout, … putridity between the toes, whitlow, [pain and injuries] from wearing tight shoes.” (Kneipp, 1901, p.183)

For relieving chapped hands and feet, the affected parts were wrapped with a warm compress soaked in hay flower decoction for “half a hour to an hour then immediately plunged into cold water for three minutes. As a strengthening measure, the dipping into cold water may be repeated some hours later.” (Lust, 1902, p.185) Kneipp cites the case of a man suffering from gout; after a hay flower compress and foot bath, his gout was relieved after an hour.

Oat Straw Foot Bath

The oat straw bath was prepared by making a strong decoction with oat straw by boiling for 30 minutes. (Kneipp, 1901, p.183) The liquid was then cooled to the desired temperatures of 88° to 90° F / 31° to 32° C, and the foot bath lasted for 30 to 40 minutes. (Kneipp, 1901, p.183) The oat straw foot bath was heralded by Kneipp as the supreme salubrious method for the feet. He asserts, “According to my experience these foot baths are unsurpassed as regards to dissolving every possible induration of the foot.” (Kneipp, 1901, p.183) The list of indications for this foot bath included: “knots, … gout, articular disease, podagra [gout of the big toe], corns, suppurating ingrown nails, and blisters.” (Kneipp, 1901, p.183)

A man with a suppurating wound from removing a corn from his toe went to Kneipp, who prescribed 3 oat straw foot baths and compresses soaked in the decoction applied to the whole foot to above the ankle. After 4 days, the toe that had been near danger of blood poisoning was completely healed. (Kneipp, 1901, p.183)

With the exception of the salt and wood ash foot bath, Kneipp did not prescribe these warm herbal foot baths without concluding with other water applications. In most cases, the treatment would involve a cold water application. In cases with suppuration and danger of necrosis, Kneipp would instruct the patient to take a warm bath after the foot bath, to be followed with a cold bath. For varices, Kneipp cautioned, “The foot bath ought never to reach higher than the beginning of the calf, and never exceed the temperature of 88° F / 31° C.” (Kneipp, 1901, p.184)

Hot Foot Bath

The hot foot bath was not endorsed by Kneipp, but others such as Hoegen and Lust considered it the bath to be used the most. The entire feet were immersed in a tub containing hot water of 102° F / 39° C, and the temperature was gradually increased until 120° F / 49° C ° was reached. Lust recommended, “All that is required is to sit with the feet immersed in water as hot as can be borne, for a half hour or more, maintaining the maximum degree of heat in the water by pouring more boiling water in from time to time.” (Lust, 1927, p.433) The duration of the foot bath ranged from 5 to 30 minutes. (Hoegen, 1917, p.314) Lust also advised that “the body be well covered by a blanket, and that copious quantities of hot drinks may be taken. After a half hour or more immersion, the feet should be carefully dried and the patient placed in bed and carefully covered.” (Lust, 1927, p.433) Hoegen claimed excellent results “in cases of sprained ankle, neuralgia and gout.” (Hoegen, 1917, p.314) Lust used the hot foot bath for patients at the first stages of a flu or cold. Lust notes, “Usually it will be found that all symptoms of deficient circulation, and the premonitory chill of the cold will have disappeared by morning.” (Lust, 1927, p.433)

The hot foot bath also accompanied a cold sitz bath.

Alternate Foot Baths

In the alternate foot bath, the feet are placed in 2 contrasting temperatures of water: hot alternating with cold. My first experience of the “alternate foot bath” occurred during one of my spa excursions. Throughout Europe’s spa and Balneotherapy facilities are different versions of the alternative or contrast foot bath. So important is this therapy in European spas, that no spa is complete without having some form of this therapy. There are many ways to achieve an alternate foot bath and there are many reasons for administering them. Let’s probe into Lust’s methodology. Two tubs are needed.

Pour hot water [100° to 110° F / 38° to 43° C] into one tub, and cold water into the other tub. The bather keeps his feet up to the knee for five minutes in the warm water, then about one minute in the cold water; then again, three to five minutes in the warm, and one minute in the cold water. The procedure can be repeated two, three or four times, as the patient wishes. (Lust, 1904, p.62)

After the foot bath, care is taken to dry the feet well and to engage in exercise to warm the body. Lust reminds us to “remember that the cold water must be used last.” (Lust, 1904, p.62)

Another who embraced the alternate foot bath was J. Waterloo Dinsdale, MD. He recommended for those abstainers of cold water applications to try the alternate foot bath before retiring to bed at night. He adds, “Put the feet in hot water for two minutes, then in the cold for one minute. Repeat twice. Then dry thoroughly and get into bed. The pleasant glow should last well through the night.” (Dinsdale, 1910, p.753)

The object of the hot and cold alternate foot bath was to mobilize blood from the head and upper body. Used to relieve blood congestion in the head, insomnia or toothache, these baths were most often prescribed before bed. M. N. Bunker, a Physical Culture practitioner, advised having 2 pails of cold and hot water side by side. “Put the feet into the latter and slowly add warm water; the feet are to become thoroughly heated. After five to ten minutes, they must be quickly immersed into the cold water, left there for one minute and then plunged back into the hot water.” (Bunker, 1914, p.690)

Hoegen’s alternate foot bath had slight variations. First, he used hot water in the contrast tub, and second, the time spent in it was shorter in duration, 2 to 3 minutes before plunging the feet into the cold tub for 30 seconds. (Hoegen, 1917, p.314) The procedure of alternating hot and cold was repeated several times. Hoegen noted, “This alternate foot bath is excellent in chilblains, cold and sweating feet.” (Hoegen, 1917, p.314) A key element of the alternate foot bath is that the hot and cold is repeated a few times and the bath ends always in the cold water.

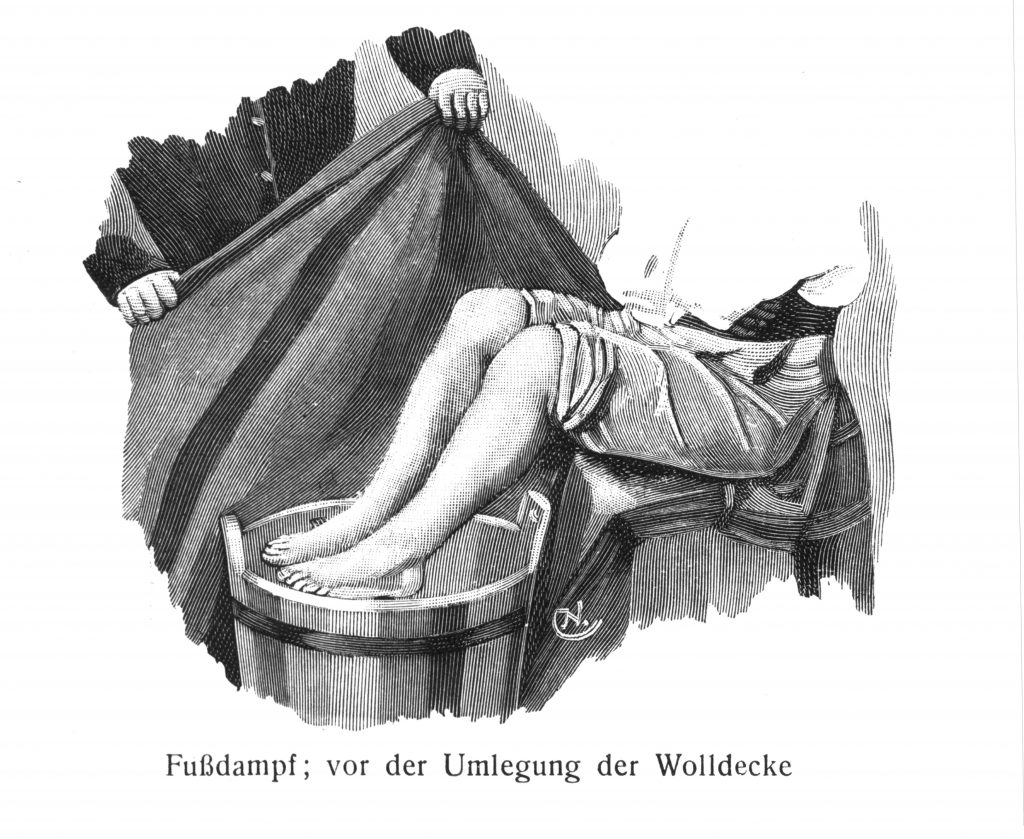

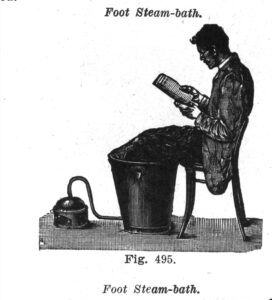

Foot Steam Bath

The foot steam bath is conducted much like the partial steam baths discussed in a previous NDNR article. Kneipp’s foot steam bath: “A rather wide and thick blanket is placed lengthwise on a chair, upon which the patient sits down with bare feet and legs. A wooden foot bath is a little more than half filled with boiling water and put before [the patient].” (Kneipp, 1899, p.78) A foot stool that is taller than the level of water in the tub is placed inside for the feet to rest on. Once the patient is seated and securely wrapped up, preventing any leakage of steam, the foot steam bath is ready to go.

Lust recommended using a high vessel filled 1/3 with boiling water and fitted with a perforated board or a piece of wood that could support the feet to rest on. The legs, feet, and vessel are covered with a woolen blanket, taking care that it reaches the floor so that no escape of the steam is possible. (Lust, 1904, p.108) “Duration of the bath is 20 to 30 minutes; after that a cold ablution of the feet up to the knees should be taken.” (Lust, 1904, p.108)

The steam or “vapor foot bath is always followed by a cooling application which depends on the [extent] of perspiration.” (Kneipp, 1899, p.78) Kneipp provides his recommendations for the follow-up of cold water applications:

If only the feet and legs as far as the knees are sweating, a quick cold ablution with a towel will suffice; stronger persons may take a knee gush [see past NDNR article]. If the thighs and abdomen are in perspiration, a half bath is sufficient; but if the whole body is seized with perspiration, then the whole body must also be cooled, either by a half bath with washing off the upper body, or by a full bath, or a whole ablution. (Kneipp, 1899, p.78)

The foot steam bath relieved foul foot odor, reduced edema, and brought warmth back to cold feet. Kneipp’s list of benefits include: “persons suffering from whitlows, [ingrown toe nails], blood poisoning due to wrong treatment of corns, … spasmodic complaints of bowels, … [congestive] headaches.” (Kneipp, 1899, p.78)

The Foot Bandage

The word “bandage” refers to a compress and was used to describe various treatments devised by Kneipp. “The foot bandage covers the foot and reaches above the ankle … The foot bandage is formed from a one or two fold linen cloth wrapped carefully round the foot, but not so tight as to prevent free circulation.” (Kneipp, 1909, p.629) Kneipp continues with his instructions: “The bandage may be kept on from one to two hours, but must be renewed at the end of the first hour.” (Kneipp, 1909, p.629) These foot bandages were applied cold to improve blood circulation to the feet and to relieve pains from ill-fitting shoes.

The application of warm bandages involved the addition of herbal decoctions. One of Kneipp’s rules was that there be no warm applications on their own. To remove morbid matter or deposits in the feet, “the hay flower bandage is generally put on warm, as its power of dispersing is then stronger.” (Kneipp, 1909, p.629) A linen cloth, like the one applied for the cold foot bandage, soaked in a warm hay flower decoction can also be substituted for a linen sock. The same procedure for the wet sock treatment is used with the warm hay flower sock treatment.

The hay flower sock treatment and bandage “is an admirable remedy for all pains in the bones of feet and ankles and for swelling resulting from blows or too much walking. But for swelling [edema] in the feet produced by mischief in other parts of the body a warm bandage would increase the swelling and intensify the heat.” (Kneipp, 1909, p.629)

Olive Oil Before Bed

- Herbert Miller, a Physical Culturist offers an old treatment for the feet using olive oil. He recommends, “While the feet need not be washed in water very often, they should be thoroughly rubbed with olive oil at least once a week, before going to bed.” (Miller, 1903, p.187)

Last But Not Least, Barefoot

Kneipp embraced the habits of simplicity and endorsed those habits for the purpose of hardening the body. He was born into poverty and understood intimately the simple way of living. “The causes of many sicknesses he found to lie in departures from the plain habits of life.” (Lust, 1905, p.169) Having grown up without shoes himself until his 20th year, Kneipp advocated strongly that “going barefoot not only hardens the body, but it is also an excellent curative.” (Lust, 1905, p.169) Barefoot walking must start with baby steps. “One should begin with a short walk in the open air … but as soon as the feet begin to get cold, stockings and shoes have to be put on; as long as the feet are warm, people will not catch cold.” (Lust, 1905, p.169-170)

Lust was very fond of barefoot walking, and those who visited the Jungborn in Butler, New Jersey, were sure to shed their socks and shoes. Barefoot walking was a method of hardening or building up resistance to disease. It was also a prophylactic for those leading sedentary lives. Lust claimed that barefoot walking was “a preventative for blood congestion … and a panacea against all nervous troubles and weaknesses.” (Lust, 1905, p.170)

Cold Wet Socks

Having sustained multiple fractures of my own foot, I have learned to minimize pain by using cold wet socks and peloids (medicinal peat mud). At times, the tango with pain that I experience can be so severe that I must crawl if I want to move, and this can be difficult if there is any urgency. How lucky we are to have the cold wet sock treatment, as this is one of the most versatile and accessible treatments to relieve foot pain. I am assuming that we all know the cold wet sock treatment. All that is needed is a pair of socks and cold water. To prevent loss of heat from the cold wet socks, put on another pair of dry heavy wool socks. Handy and simple! After applying the cold wet socks to my feet, the pain dramatically diminishes and no longer keeps me awake. The sleep that comes with cold socks is remarkable. I highly recommend them for those having difficulty falling asleep. For pain, the wet socks work like a charm!

Peat Peloids

My other love, peat peloids, is immense. The minerals in peat are remarkable, and I have included it with the foot bath in all of its temperatures – cold, warm, and hot – by adding peat mud to the foot bath. Soaking for 20 to 30 minutes brings relief to the pain and helps me walk again.

A peloid foot bath can miraculously relieve gout pain and pitting edema. I have had patients become pain-free after 1 or 2 foot baths when using peloids.

Summary

The choices that we have in hydrotherapy enable the best care for our patients. The simple foot bath needs a dusting off and to be brought back into our practices. I leave you with a quote from Benedict Lust: “Do not think for a moment that many applications must give much relief, but remember that Nature does not allow herself to be mastered in any way. As we know that the vital strength of the body, if great enough, can cure us in almost every case, our duty lies in supporting Nature in this respect.” (Lust, 1904, p.60) Knowing how to use these simple hydrotherapy applications correctly and safely, we can offer much comfort and healing for our patients.

Sussanna Czeranko ND, BBE, incorporates “nature-cure” approaches to primary care by including balneotherapy, breathing therapy, and nutrition into her naturopathic practice. Dr Czeranko is a faculty member working as the Rare Books curator at NCNM and is currently compiling a 12-volume series based upon the journals published early in the last century by Benedict Lust. Four of the books have been published: Origins of Naturopathic Medicine, Philosophy of Naturopathic Medicine, Dietetics of Naturopathic Medicine, and Principles of Naturopathic Medicine. In addition to her work in balneotherapy, she is the founder of the Breathing Academy, a training institute for naturopaths to incorporate a scientific model of breathing therapy called Buteyko into their practice. She is a founding board member of the International Congress of Naturopathic Medicine and a member of the International Society of Medical Hydrology.

Sussanna Czeranko ND, BBE, incorporates “nature-cure” approaches to primary care by including balneotherapy, breathing therapy, and nutrition into her naturopathic practice. Dr Czeranko is a faculty member working as the Rare Books curator at NCNM and is currently compiling a 12-volume series based upon the journals published early in the last century by Benedict Lust. Four of the books have been published: Origins of Naturopathic Medicine, Philosophy of Naturopathic Medicine, Dietetics of Naturopathic Medicine, and Principles of Naturopathic Medicine. In addition to her work in balneotherapy, she is the founder of the Breathing Academy, a training institute for naturopaths to incorporate a scientific model of breathing therapy called Buteyko into their practice. She is a founding board member of the International Congress of Naturopathic Medicine and a member of the International Society of Medical Hydrology.

References

- Bunker, M. N. (1914). Essentialities in Physical Culture. The Naturopath and Herald of Health, XIX (10), 688-691.

- Dinsdale, J. W. (1910). Keeping warm in winter. The Naturopath and Herald of Health, XV (12), 753-754.

- Hoegen, J. A. (1917). Hydrotherapy. Herald of Health and Naturopath, XXII (5), 311-316.

- Kneipp, S. (1891). My Water Cure. London, England: William Blackwood & Sons Publishing, pp. 272.

- Kneipp, S. (1901). Water applications, the vapor foot bath. The Kneipp Water Cure Monthly, II (3), 78-79.

- Kneipp, S. (1901). Water applications, baths. The Kneipp Water Cure Monthly, II (7), 183-184.

- Kneipp, S. (1909). The foot bandage. The Naturopath and Herald of Health, XIV (10), 629-630.

- Lust, B. (1900). For the little children. The Kneipp Water Cure Monthly, I (2), 28.

- Lust, B. (1902). Diseases, how to treat them according to the Kneipp system. The Naturopath and Herald of Health, III (4), 185-186.

- Lust, B. (1904). A naturopathic silhouette. The Naturopath and Herald of Health, V (1), 4-7.

- Lust, B. (1904). Naturopathy, general remarks about treatment of the sick. The Naturopath and Herald of Health, V (3), 60-62.

- Lust, B. (1905). Going barefoot. The Naturopath and Herald of Health, VI (6), 168-170.

- Lust, B. (1909). The natural method of healing. The Naturopath and Herald of Health, XIV (6), 368-373.

- Miller, W. H. (1903). The care of the feet. The Naturopath and Herald of Health, IV (7), 186-187.