Tolle Causam

Lauren Tessier, ND

When the phrase “fungal infections” is uttered, what are the first 3 pathologies that come to mind? Perhaps you think of the deadly, invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. Or maybe you specialize in women’s health and immediately think of vaginal candidiasis. Or maybe you are a primary care physician and you immediately picture the common case presentations of ringworm. In this exercise, it is likely that tinea, in any of its various iterations – tinea corporis, tinea pedis, tinea curis, tinea capitis, etc – came to mind. And understandably so, as anywhere from 20% to 25% of the population worldwide suffers with a superficial fungal infection.1

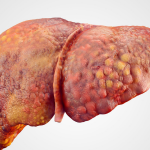

Dermatophytic Skin Infections

Tinea, in all its forms, is caused by dermatophytes, which are fungi with a predilection to infect the superficial aspects of the body that are rich in keratin, including the hair, skin, and nails. Although there are upwards of 40 different species of dermatophytes across 7 genera, only about 25% of these dermatophytes are common causes of superficial cutaneous fungal infections.1-3 Some of the more common dermatophytes include fungi from the genera of Microsporum, Trichophyton, and Epidermophyton.4

Dermatophytic infections are typically diagnosed by clinical presentation, and are traditionally characterized by an annular arrangement of scaling erythematous patches, accompanied by central clearing and peripheral enlargement.5 Although dermatophytes are a common cause of cutaneous infection, they are not the only cause. In a 2016 human study of antifungal efficacy, 58 fungal species were identified in dermatological infections among 53 patients. However, of these samples, only 19% demonstrated dermatophytes, while nearly 70% were non-dermatophyte hyaline molds.6 Such statistics invite the clinician to turn a curious eye to the realm outside of typical dermatophytic ringworm infections.

Non-dermatophytic Infections

The research thus clearly demonstrates that non-dermatophytes are able to infect the skin. Two major infective classes include hyaline fungi and dematiaceous fungi.

Hyaline fungi are well known in the indoor environmental and agricultural realms, but they also have a track record of causing numerous types of infections, with certain species more commonly involved than others. Hyaline fungi consist of 2 classes. These are distinguished by whether or not they have compartmentalized divisions in their hyphae, which are the long, branching, filamentous tubes that create “fuzzy”-appearing mycelium. Septate fungi include the Aspergillus, Penicillium, Paecilomyces, and Fusarium genera, while the Zygomycetes phylum consists of mostly aseptate fungi.2

Dematiaceous fungi are known for their ability to produce melanin in their cell walls, including the cell walls of their hyphae and conidia, or spores. These fungi have been isolated from human skin and, as such, may be responsible for some infections that cause melanotic changes. Common genera of dematiaceous fungi include Aureobasidium, Curvularia, Exophiala, Hormonema, and Madurella.7

Atypical Fungal Dermatology

Tinea Incognito

Suffice it to say, the above discussion of common superficial fungal infections is grossly brief; however, the focus of this article is atypical presentations of dermatological fungal pathologies. Perhaps one of the most interesting, and redundantly named, fungal disorders, is tinea aytpica, also known as tinea incognito; which was first described in 1968.8 Although dermatophytic in origin, tinea incognito is aptly named, as it can take on the appearance of other skin pathologies.8 Previously, tinea incognito (TI) was thought to result from corticosteroid use, as the use of these drugs causes a suppression of the cutaneous immune system, thereby allowing dermatophyte infections to go unchecked.3,9,10 However, the use of such medications has come to be considered correlative of TI (as a result of improper diagnosis and management) rather than a cause. This is because other medications, such as antibiotics, antivirals, and nonsteroidal immunosuppressive agents, have also been correlated with its presence.5,8,11,12

Tinea incognito differs from typical tinea in its appearance. For example, the clinical presentation of TI may demonstrate less-defined margins, hyperpigmentation, swelling, bullae, induration, increased severity of inflammation, vesicles, pustules, and central scaling or follicular papules rather than central clearing.5,13 It is estimated that nearly 2.5% of all the annually diagnosed dermatophyte infections manifest as TI.14 Distribution is nearly equal across all age groups, with slightly lesser occurrence in the first 5 years of life and in those over the age of 76.14 Research demonstrates that TI results most often from infection by Microsporum canis,5,14 Trichophyton rubrum,5,14-19 and Trichophyton mentagrophytes5,11,14,20 species of dermatophytes. In clinical presentation, TI often resembles other skin pathologies, such as psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, eczematous dermatitis, rosacea, lupus erythematosus discoid-like lesions, impetigo, pemphigus foliaceus, polymorphous light eruption, seborrhea, contact dermatitis, bacterial infections, neurodermatitis, lichen planus, and herpes simplex.3,5,13-17,21-28,29

Acne

Acne is largely considered to be due to Cutibacterium acnes, also known as Propionibacterium, and other naturally occurring flora of the skin, including Staphylococcus spp.30,31 However, research indicates that the Malassezia yeast species are also present and may potentially play a role.32-34 Malassezia yeast exhibit lipase activity, which is required to degrade sebum from the follicle into its free fatty acid and glycerol components. In fact, Malassezia yeasts may demonstrate 100 times more lipase activity than Propionibacterium acnes.35 The inflammatory free fatty acids produced from the degraded sebum attract neutrophils to the follicle.36 Compounding the chemotactic effect of the free fatty acids, the presence of Malassezia yeast promotes the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines from nearby keratinocytes and mononuclear cells37,38 – thus, the development of acne.

A 2016 study of the flora from acne-prone skin demonstrated via quantitative PCR a higher amount of Malassezia yeast in the follicles than on the skin surface.33 Moreover, the severity of inflammatory acne positively correlated with the concentration of Malassezia yeast, specifically Malassezia restricta and Malassezia globosa. Meanwhile, neither Staphylococcus nor Propionibacterium spp concentrations correlated with acne severity.33

In 2018, a total of 217 cases of acne vulgaris, presenting with papulopustular or comedonal acne, were studied.33 A quarter of the patients were diagnosed with Malassezia folliculitis, and nearly 70% of these were treated with antifungal treatment. This treatment resulted in a decrease of papulopustular or comedonal lesions by at least 50% in nearly 70% of those undergoing antifungal treatment. This study suggests that Malassezia folliculitis may present as acne vulgaris, or even that acne vulgaris and Malassezia folliculitis (MF) may occur concomitantly.39 MF, once referred to as Pityrosporum folliculitis,40 commonly presents on the face, upper back, chest, lateral arms, and trunk,40-42 not unlike the presentation of acne vulgaris, which also occurs on the face, trunk, back, and upper arms.31

Cutaneous Histoplasmosis

Histoplasmosis is recognized as one of the most prevalent respiratory mycoses worldwide. It is quite predominant in the midwestern part of the United States, and is endemic in the central and eastern states surrounding the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys, including Ohio, Missouri, Kentucky, Illinois, and Tennessee.43 Although histoplasmosis is commonly known as a respiratory illness, it can present with cutaneous manifestations. Although such manifestations are more common in the immunocompromised, they may still occur in the immunocompetent in endemic areas.

Cutaneous manifestations of histoplasmosis may begin as a painless chancre or ulcer,43 and over time may evolve in appearance to resemble pustules, nodules, erythematous or keratotic papules, plaques with and without crusting or keratotoses, erosions, ulcers of the mucosa, acne-like lesions, molluscum contagiosum,44 focal and systemic dermatitis, punched-out ulcers, purpura,44-46 rosacea, polymorphous erythema, hyperpigmentation, or cutaneous malignancy.47-52 Although the bulk of the aforementioned references cited involve immunocompromised patients as a result of HIV and AIDs, physicians should still be aware of such presentations, as immune compromise can result from many chronic illnesses, albeit potentially to a lesser degree.

Notable Mentions

Seborrheic Dermatitis

Seborrhea was once widely considered to be directly caused by yeasts of the Malassezia genera. However, contrary research suggests that this typically commensal flora is non-problematic and only becomes pathogenic in the case of immune system dysfunction53,54; this suggests that the presence of Malessezia is correlative rather than causative in the pathogenesis of seborrhea. With that being said, however, various antifungals have shown documented efficacy in the treatment of seborrhea.55-62 Moreover, dandruff, considered by some to be a mild, non-inflammatory form of seborrhea, is often correlated to Malassezia colonization63,64 and, as such, is responsive to antifungal treatment.34-67

Rosacea

As stated above, tinea incognito may mimic rosacea,2,5,14,68 thus inferring that dermatophytes can elicit such a clinical appearance. However, other fungi, such as certain species of Candida69,70 and Sporothrix schenckii,71 have also been implicated in case reports of patients with rosacea-like lesions. One study, in particular, demonstrated some improvement of papulopustular rosacea using the antifungal terbinafine. Interestingly, the authors surmised that the beneficial effects were likely due to an off-label anti-inflammatory action of terbinafine; curiously, this assumption was made despite not having cultured any of the papulopustular lesions in the subjects studied.71 However, other studies have also demonstrated a beneficial effect of antifungal drugs, such as ketoconazole72 and bifonazole.73,74

Infections with Common Indoor Molds

Thus far, many of the atypical fungal dermatological presentations discussed above include dermatophytes and yeast. However, there are numerous instances where environmental molds have been documented to infect humans. Wallemia sebi, a common mold found in water-damaged buildings, is known to cause infections in the nails and skin.75,76 These infections have not been widely documented since the mid-20th century. This may be due to underdiagnosis, as they are slow-growing in nature. However, curiously enough, of the cases documented, these infections can occur in immunocompetent individuals.77 Other common environmental molds known to cause cutaneous infections in humans include Aspergillus fumigatus,78-82,84,85 Aspergillus niger,86-90 and Aspergillus flavus84; with A flavus reportedly causing most of these cases.91-93 Such infections, known as cutaneous aspergillosis, typically occur in the immunocompromised; however, there are instances of occurrences in immunocompetent individuals.79,80,84-86,90

A Note on Diagnosis

Returning to a differential diagnosis list in response to treatment failure is an overlooked and underappreciated tool in the physician toolbox. Treatment failures of presumptive and clinical diagnoses (often required in the fast-paced primary-care setting), although frustrating, serve as invaluable case information. Just as you would consider a fungal etiology for treatment-resistant chronic sinusitis, treatment-resistant dermatological complaints are no different. Cutaneous complaints that are non-responsive to corticosteroids, antibiotics, and even antivirals26 and antiparasitics,94 warrant a fungal work-up. However, these treatment failure algorithms are not limited to pharmaceutical drugs; treatment failures in response to an elimination diet, UV applications, botanicals, nutraceuticals, and other supplements should also be included.

When needing to assess for atypical cutaneous fungal infections, not only should a KOH prep be used, but also a culture (and sensitivity, if available). To further complicate matters, it is important that one be aware that a fungal culture may present with a false negative, which may be the result of improper growing medium, inadequate sampling, slow growth, or even failure to simply indicate a fungal culture on the lab requisition. In the case of a negative fungal culture, a histopathological sample may be necessary for the final diagnosis.14,95 If all of this seems too complicated or overwhelming, a specifically stated referral – requesting a rule-out of fungal etiology – to a dermatologist you trust is completely reasonable.

References:

- Havlickova B, Czaika VA, Friedrich M. Epidemiological trends in skin mycoses worldwide. Mycoses. 2008;51 Suppl 4:2-15. Erratum in: Mycoses. 2009;52(1):95.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Arenas R, Moreno-Coutiño G, Vera L, Welsh O. Tinea incognito. Clin Dermatol. 2010;28(2):137-139.

- Laniosz V, Wetter DA. What’s new in the treatment and diagnosis of dermatophytosis? Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2014;33(3):136-139.

- Atzori L, Pau M, Aste N, Aste N. Dermatophyte infections mimicking other skin diseases: a 154-person case survey of tinea atypica in the district of Cagliari (Italy). Int J Dermatol. 2012;51(4):410-415.

- Mohd Nizam T, Binting RA, Mohd Saari S, et al. In Vitro Antifungal Activities against Moulds Isolated from Dermatological Specimens. Malays J Med Sci. 2016;23(3):32-39.

- Revankar SG, Sutton DA. Melanized fungi in human disease. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23(4):884-928.

- Ive FA, Marks R. Tinea incognito. Br Med J. 1968;3(5611):149-152.

- Solomon BA, Glass AT, Rabbin PE. Tinea incognito and “over-the-counter” topical potent topical steroids. Cutis. 1996;58(4):295-296.

- Fisher DA. Adverse effects of topical corticosteroid use. West J Med. 1995;162(2):123-126.

- Sánchez-Castellanos ME, Mayorga-Rodriguez JA, Sandoval-Tress C, Hernandez-Torres M. Tinea incognito due to Trichophyton mentagrophytes. Mycoses. 2007;50(1):85-87.

- Siddaiah N, Erickson A, Miller G, Elston DN. Tacrolimus-induced tinea incognito. Cutis. 2004;73(4):237-238.

- Ziemer M, Seyfarth F, Elsner P, Hipler UC. Atypical manifestations of tinea corporis. Mycoses. 2007;50 Suppl 2:31-35.

- Romano C, Maritati E, Gianni C. Tinea incognito in Italy: a 15-year survey. Mycoses. 2006;49(5):383-387.

- Serarslan G. Pustular psoriasis-like tinea incognito due to Trichophyton rubrum. Mycoses. 2007;50(6):523-524.

- Ghislanzoni M. Tinea incognito due to Trichophyton rubrum responsive to topical therapy with isoconazole plus corticosteroid cream. Mycoses. 2008;51 Suppl 4:39-41.

- Nenoff P, Mügge C, Hermann J, Keller U. Tinea faciei incognito due to Trichophyton rubrum as a result of autoinoculation from onychomycosis. Mycoses. 2007;50 Suppl 2:20-25.

- Szepietowski JC, Motusiak L. Trichophyton rubrum autoinoculation from infected nails is not such a rare phenomenon. Mycoses. 2008;51(4):345-346.

- Kastelan M, Massari LP, Brajac I. Tinea incognito due to Trychophyton rubrum–a case report. Coll Anthropod. 2009;33(2):665-667.

- Lange M, Jasiel-Walikowska E, Nowichi R, Bykowska B. Tinea incognito due to Tricophyton mentagrophytes. Mycoses. 2010;53(5):455-457.

- Jorquera E, Moreno JG, Camacho F. Tinea faciei: epidemiology. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1992;119(2):101-104. [Article in French]

- Meymandi S, Wiseman MC, Crawford RJ. Tinea faciei mimicking cutaneous lupus erythematous: a histopathologic case report. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48(2 Suppl):S7-S8.

- Alteras I, Sandbanyk M, David M, Segal R. 15-year survey of tinea faciei in the adult. Dermatologica. 1983;177(2):65-69.

- Virgili A, Corazza M, Zampino MR. Atypical features of tinea in newborns. Pediatr Dermatol. 1993;10(1):92-93.

- Atzori L, Pau M, Aste N. Erythema multiforme ID reaction in atypical dermatophytosis: case report. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17(6):699-701.

- Aste N, Pau M, Aste N, Atzori L. Tinea corporis mimicking herpes zoster. Mycoses. 2011;54(5):463-465.

- Aste N, Pau M, Biggio P. Atypical mycoses–second part: tinea corporis with the clinical appearance of contact dermatitis. Rass Med Sarda. 1988;91:19-26.

- Guenova E, Hoetzencker W, Schaller M, et al. Tinea incognito hidden under apparently treatment-resistant pemphigus foliaceus. Acta Derm Venereol. 2008;88(3):276-277.

- Adams A, Chia C, Warschaw K. Tinea incognito masquerading as a polymorphous eruption in a patient on anti–TNF-alfa therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62(3 Suppl 1):AB84.

- Nakase K, Nakaminami H, Takenaka Y, et al. Relationship between the severity of acne vulgaris and antimicrobial resistance of bacteria isolated from acne lesions in a hospital in Japan. J Med Microbiol. 2014;63(Pt 5):721-728.

- Sutaria AH, Masood S, Schlessinger J. Acne Vulgaris. Last updated December 13, 2019. StatPearls [Internet]. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459173/. Accessed September 15, 2019.

- Numata S, Akamatsu H, Akaza N, et al. Analysis of facial skin-resident microbiota in Japanese acne patients. Dermatology. 2014;228(1):86-92.

- Akaza N, Akamatsu H, Numata S, et al. Microorganisms inhabiting follicular contents of facial acne are not only Propionibacterium but also Malassezia spp. J Dermatol. 2016;43(8):906-911.

- Till AE, Goulden V, Cunliffe WJ, Holland KT. The cutaneous microflora of adolescent, persistent and late-onset acne patients does not differ. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142(5):885-892.

- Akaza N, Akamatsu H, Takeoka S, et al. Malassezia globosa tends to grow actively in summer conditions more than other cutaneous Malassezia species. J Dermatol. 2012;39(7):613-616.

- Webster GF. Inflammation in acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33(2 Pt 1):247-253.

- Akaza N, Akamatsu H, Takeoka S, et al. Increased hydrophobicity in Malassezia species correlates with increased proinflammatory cytokine expression in human keratinocytes. Med Mycol. 2012;50(8):802-810.

- Kesavan S, Walters CE, Holland KT, Ingham E. The effects of Malassezia on pro-inflammatory cytokine production by human peripheral blood mononuclear cells in vitro. Med Mycol. 1998;36(2):97-106.

- Pürnak S, Durdu M, Tekindal MA, et al. The Prevalence of Malassezia Folliculitis in Patients with Papulopustular/Comedonal Acne, and Their Response to Antifungal Treatment. Skinmed. 2018;16(2):99-104.

- Abdel-Razek M, Fadaly G, Abdel-Raheim, al-Morsy F. Pityrosporum (Malassezia) folliculitis in Saudi Arabia– diagnosis and therapeutic trials. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1995:20(5):406-409.

- Yu HJ, Lee SK, Son SJ, et al. Steroid acne vs. Pityrosporum folliculitis: the incidence of Pityrosporum ovale and the effect of antifungal drugs in steroid acne. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37(10):772-777.

- Durdu M, Guran M, Ilkit M. Epidemiological characteristic of Malassezia folliculitis and use of the May-Grünwald-Giemsa stain to diagnose the infection. Diagon Microbio Infect Dis. 2013;76(4):450-457.

- Chang P, Rodas C. Skin lesions in histoplasmosis. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30(6):592-598.

- Couppié P, Clyti E, Nacher M, et al. Differences in histoplasmosis and AIDS Acquired immnunodeficiency syndrome-related oral and/or cutaneous histoplasmosis: a descriptive and comparative study of 21 cases in French Guiana. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41(9):571-576.

- Couppié P, Aznar C, Carme B, Nacher M. American histoplasmosis in developing countries with a special focus on patients with HIV: diagnosis, treatment and prognosis. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2006;19(5):443-449.

- Rosenberg JD, Scheinfeld NS. Cutaneous histoplasmosis in patients with acquired histoplasmosis inhuman immunodeficiency virus infected patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23:442-448.

- Eidbo J, Sanchez RL, Tschen JA, Ellner KM. Cutaneous manifestations of histoplasmosis in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am J Surg Pathol. 1993;17(2):110-116.

- Rosenberg JD, Scheinfeld NS. Cutaneous histoplasmosis in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Cutis. 2003;72(6):439-445.

- Cole C, Cohen PR, Satra KH, Grossman ME. The concurrent presence of systemic disease of systemic disease pathogens and cutaneous Kaposi’s sarcoma in the same lesion: Histoplasma capsulatum and Kaposi’s sarcoma coexisting in a single skin lesion in a patient with AIDS. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26(2 Pt 2):285-287.

- Golda N, Feldman M. Histoplasmosis clinically imitating cutaneous malignancy. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35 Suppl 1:26-28.

- Merin MR, Eisen D. Cutaneous histoplasmosis mimicking cutaneous malignancy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62(3 Suppl 1):AB84.

- Radhakrishnan S, Adulkar NG, Kim U. Primary cutaneous histoplasmosis mimicking basal cell carcinoma of the eyelid: A case report and review of literature. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2016;59(2):227-228.

- Bergbrant IM, Johansson S, Robbins D, et al. An immunological study in patients with seborrhoeic dermatitis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1991;16(5):331-338.

- Faergemann J, Bergbrant IM, Dohsé M. Seborrhoeic dermatitis and Pityrosporum (Malassezia) folliculitis: characterization of inflammatory cells and mediators in the skin by immunohistochemistry. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144(3):549-556.

- Marks R, Pearse AD, Walker AP. The effects of a shampoo containing zinc pyrithione on the control of dandruff. Br J Dermatol. 1985;112(4):415-422.

- Opdyke DL, Burnett CM, Brauer EW. Anti-seborrhoeic qualities of zinc pyrithione in a cream vehicle. II. Safety evaluation. Food Cosmet Toxicol. 1967;5(3):321-326.

- Faergemann J. Seborrhoeic dermatitis and Pityrosporum orbiculare: treatment of seborrhoeic dermatitis of the scalp with miconazole hydrocortisone (Daktacort), miconazole and hydrocortisone. Br J Dermatol. 1986;114(6):695-700.

- Segal R, David M, Ingber A. Treatment with bifonazole shampoo for seborrhea and seborrheic dermatitis: a randomized, double-blind study. Acta Derm Venereol. 1992;72(6):454-455.

- Shiri J, Amachai B. Treatment of seborrheic dermatitis of the scalp and dandruff with a shampoo containing 1% bifonazole (Agispor shampoo). J Dermatolog Treat. 1998;9(2):95-96.

- Zienicke H, Korting HC, Braun-Falco O, et al. Comparative efficacy and safety of bifonazole 1% cream and the corresponding base preparation in the treatment of seborrheic dermatitis. Mycoses. 1993;36(9-10):325-331.

- Rigopoulos D, Katsambas A, Antoniou C, et al. Facial seborrheic dermatitis treated with fluconazole 2% shampoo. Int J Dermatol. 1994;33(2):136-137.

- Faergemann J, Jones TC, Hettler O, Loria Y. Pityrosporum ovale (Malassezia furfur) as the causative agent of seborrhoeic dermatitis: new treatment options. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134 Suppl 46):12-15.

- Danby FW, Maddin WS, Margesson LJ, Rosenthal D. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of ketoconazole 2% shampoo versus selenium sulfide 2.5% shampoo in the treatment of moderate to severe dandruff. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29(6):1008-1012.

- Shuster S. The aetiology of dandruff and the mode of action of therapeutic agents. Br J Dermatol. 1984;111(2):235-242.

- Bulmer AC, Bulmer GS. The antifungal action of dandruff shampoos. Mycopathologia. 1999;147(2):63-65.

- Do E, Lee HG, Park M, et al. Antifungal Mechanism of Action of Lauryl Betaine Against Skin-Associated Fungus Malassezia restricta. Mycobiology. 2019;47(2):242-249.

- Leong C, Schmid B, Buttafuoco A, et al. In vitro efficacy of antifungal agents alone and in shampoo formulation against dandruff-associated Malassezia spp. and Staphylococcus spp. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2019;41(3):221-227.

- Calcaterra R, Fazio R, Mirisola C, Baggi L. Rosacea-like tinea incognito due to Trichophyton mentagrophytes vr. mentagrophytes. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2013;21(4):263-264.

- Massone C, Propst E, Kopera D. Rosacealike dermatitis with Candida albicans infection. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142(7):945-946.

- Alomar Muntañola A, Gimenez Camarasa JM. Rosacea caused by Candida. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 1974;65(3-4):183-184. [Article in Spanish]

- Serdar ZA, Yaşar Ş. Efficacy of 1% terbinafine cream in comparison with 0.75% metronidazole gel for the treatment of papulopustular rosacea. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2011;30(2):124-128.

- Utaş S, Ünver Ü. Treatment of rosacea with ketoconazole. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venerol. 1997;8(1):69-70.

- Döring HF, Ilgner M. Therapy of rosacea with bifonazole cream–practical experiences over a 2-year period. Z Hautkr. 1986;61(7):490-494. [Article in German]

- Stettendorf S. Bifonazole–a synopsis of clinical trials worldwide. Status and outlook. Dermatologica. 1984;169 Suppl 1:69-76.

- Zalar P, Sybren de Hoog G, Schroers HJ, et al. Taxonomy and phylogeny of the xerophilic genus Wallemia (Wallemiomycetes and Wallemiales, cl. et ord. nov.). Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2005;87(4):311-328.

- Fothergill AW. Identification of dematiaceous fungi and their role in human disease. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;22 Suppl 2:S179-S184.

- Guarro J, Gugnani HC, Sood N, et al. Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis caused by Wallemia sebi in an immunocompetent host. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46(3):1129-1131.

- Barber CM, Fahrenkopf MP, Dietze-Fiedler ML, et al. Cutaneous Aspergillus fumigatus infection in a Newborn. Eplasty. 2019;19:ic13. eCollection 2019.

- Liu X, Yang J, Ma W. Primary cutaneous aspergillosis caused by Aspergillus fumigatus in an immunocompetent patient: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96(48):e8916.

- Chaturvedi R, Kolhe A, Pardeshi K, et al. Primary cutaneous aspergillosis, mimicking malignancy, a rare presentation in an immunocompetent patient. Diagn Cytopathol. 2018;46(5):434-437.

- Darr-Foit S, Schliemann S, Scholl S, et al. Primary cutaneous aspergillosis – an uncommon opportunistic infection Review of the literature and case presentation. J Dtsch Dermatolo Ges. 2017;15(8):839-841.

- Gallais F, Denis J, Koobar O, et al. Simultaneous primary invasive cutaneous aspergillosis in two preterm twins: case report and review of the literature. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17(1):535.

- Nerune SM, Arora S, Kumar M. Cytological Diagnosis of Primary Cutaneous Aspergillosis Masquerading as Lipoma in a Known Case of Lepromatous Leprosy. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11(5):ED36-ED37.

- Romano C, Miracco C. Primary cutaneous aspergillosis in an immunocompetent patient. Mycoses. 2003;46(1-2):56-59.

- Domergue V, Orlandini V, Begueret H, et al. Cutaneous, pulmonary and bone aspergillosis in a patient presumed immunocompetent presenting subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2008;135(3):217-221. [Article in French]

- Mohapatra S, Xess I, Swetha JV, et al. Primary cutaneous aspergillosis due to Aspergillus niger in an immunocompetent patient. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2009;27(4):367-370.

- Kusari A, Sprague J, Eichenfield LF, et al. Primary cutaneous aspergillosis at the site of cyanoacrylate skin adhesive in a neonate. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35(4):494-497.

- Furlan KC, Pires MC, Kakizaki P, et al. Primary cutaneous aspergillosis and idiopathic bone marrow aplasia. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91(3):381-383.

- Chung EH, Lee SY. A Case of Primary Cutaneous Scar Infection Caused by Aspergillus niger. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26(5):659-660.

- Samal P, Samal S, Raulo BC, Sahu MC. A manifestation of cutaneous aspergillosis in immunocompetent host: A rare presentation as forearm mass lesion. J Mycol Med. 2016;26(1):51-55.

- van Burik JA, Colven R, Spach DH. Cutaneous aspergillosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36(11):3115-3121.

- Chakrabarti A, Gupta V, Biswas G, et al. Primary cutaneous aspergillosis: our experience in 10 years. J Infect. 1998;37(1):24-27.

- Hedayati MT, Pasqualotto AC, Warn PA, et al. Aspergillus flavus: human pathogen, allergen and mycotoxin producer. Microbiology. 2007;153(Pt 6):1677-1692.

- Chougule A, Chatterjee D, Yadav R, et al. Granulomatous Rosacea Versus Lupus Miliaris Disseminatus Faciei-2 Faces of Facial Granulomatous Disorder: A Clinicohistological and Molecular Study. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018;40(11):819-823.

- Odom RB, James WD, Berger TG. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: W.B. Saunders; 2000.

Lauren Tessier, ND, is a licensed naturopathic physician specializing in mold-related illness. She is a nationally known speaker and is the vice president of the International Society for Environmentally Acquired Illness (ISEAI) – a non-profit dedicated to educating physicians about the diagnosis and treatment of environmentally acquired illness. Dr Tessier’s practice, “Life After Mold,” in Waterbury, VT, draws clients from all around the world who suffer from chronic complex illness as a result of environmental exposure and chronic infections. Dr Tessier’s e-booklet, Mold Prevention: 101, has been widely circulated and its suggestions implemented by many worldwide.