Laura Miller-Sickels, NMD

It is no secret that medical advancements preventing illness and disease that cause premature death are allowing current generations to live longer. As a result, the number of individuals aged 60+ is rapidly growing. According to the report from the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs there are over 700 million individuals in the 60+ age group worldwide.1 More importantly, they project 2 billion individuals over the age of 60 to be alive in the year 2050.1

This rapidly growing segment of our population leads us to an ever-increasing interest towards researching the effects of aging on organ physiology, cellular function, and clinical and laboratory presentation on disease.2 The aging process affects the endocrine system and is illustrated by the increased prevalence of thyroid dysfunction in the aging population. Identifying this issue and treating these individuals may improve the quality of life for this population. However, recent controversies within the medical community regarding the diagnosis and treatments for hypothyroidism and subclinical thyroid dysfunction have left many practitioners wondering when and how to best to treat these conditions.3

This rapidly growing segment of our population leads us to an ever-increasing interest towards researching the effects of aging on organ physiology, cellular function, and clinical and laboratory presentation on disease.2 The aging process affects the endocrine system and is illustrated by the increased prevalence of thyroid dysfunction in the aging population. Identifying this issue and treating these individuals may improve the quality of life for this population. However, recent controversies within the medical community regarding the diagnosis and treatments for hypothyroidism and subclinical thyroid dysfunction have left many practitioners wondering when and how to best to treat these conditions.3

Decreased thyroid function is common and estimated to affect about 4% of the general population in the United States, many of whom are older and female.3 More alarming is the number of individuals who go undiagnosed each year. In fact, according to a Colorado Thyroid Disease Prevalence Study, 9.9% of the 24,337 subjects who did not report taking thyroid medication were found to have undiagnosed abnormal thyroid function.4 This equates to 13 million people nationally who may be living with undiagnosed abnormal thyroid function.4

Oftentimes it can be difficult to accurately diagnose an older individual with thyroid dysfunction. As a healthcare professional one must also consider other factors such as chronic (non-thyroidal) illness and medication-induced changes in thyroid function tests.5 However, reviews have shown that after excluding these factors, there are similar results among the studies: An age-dependent decline in serum thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) and free T3, an increase in the inactive metabolite rT3 (reverse T3), and levels of serum free T4 remaining unchanged.5 (see figure)

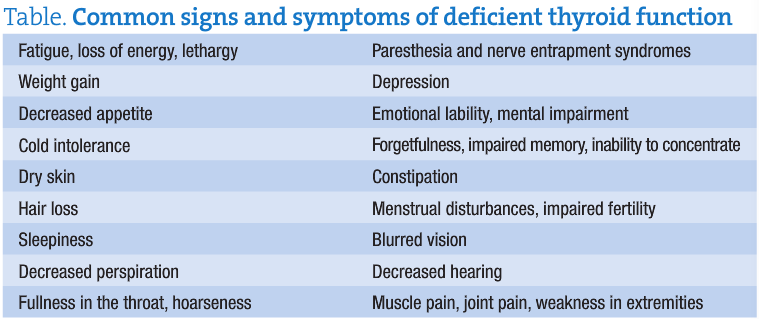

Current evidence suggests a declining thyroid function in the aging population. This results in many individuals being classified with either subclinical hypothyroidism or hypothyroidism. A study published in 2004 showed that a decreased T3 level in the older population resulted in lowered attention, depression, increased mortality, and decreased ability to perform activities of daily living.6 Subclinical hypothyroidism is defined as having normal serum free T4 levels with slightly elevated serum TSH levels; whereas hypothyroidism is classified by an elevated TSH with a decreased serum free T4. Individuals suffering from symptoms of thyroid dysfunction may not be accurately diagnosed with a thyroid disorder since their serum TSH levels may be within the normal limits of the reference range. (see table)

Recently, there has been debate regarding whether or not the reference range for serum TSH is too broad, thus contributing to the high prevalence of undiagnosed thyroid dysfunction.6 Decreasing the upper limit for the TSH reference range would impact the diagnosis and treatment of subclinical hypothyroidism worldwide. A review in The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism assessed a subset of cohorts from an earlier study, the Hanford Thyroid Disease Study (HTDS), in which serum TSH levels were measured in a general population with no evidence of thyroid disease.7 The analysis from the new study concluded that the results would support lowering the upper limit of the TSH reference range below the 4.5-5.0 µIU/mL that is often reported by clinical laboratories.7 Even after adding normal ultrasonography as a criterion for defining the normal reference population, 20% of the HTDS participants without evidence of thyroid disease had a TSH greater than 2.5 µIU/mL. Furthermore, 10.2% had a value greater than 3.0 µIU/mL.6 Based on these results, there is a general concern that an upper limit of 2.5 µIU/mL may result in inappropriate therapy for euthyroid individuals exposing them to risks from over treatment.6 The study concluded that an upper limit near 4.0 µIU/mL in addition to consideration of patient-specific factors may be the best guidelines for deciding on whether or not treatment is indicated.7 The medical history, symptoms and physical signs from the patient should be considered to help diagnose an individual with serum lab values within the normal reference range.

In recent years, there has been a vast amount of published data regarding screening and initiation of treatment for subclinical thyroid dysfunction. However, much of this data is still in conflict. The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, The Endocrine Society, and the American Thyroid Association created a panel of physicians of varied specialties to evaluate the evidence and make recommendations based on the most current information available at the time.3 It was concluded among the panelists “that the evidence supports treating patients with normal free T4 and T3 levels but with TSH concentrations below 0.1 mIU/liter or above 10 mIU/liter, whether or not the patient was symptomatic.”3 To further complicate the matter, an article found in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism presents a somewhat conflicting view toward the physicians’ panel findings. According to this article, the 3 groups agree on some issues with the panel they sponsored, but disagree with their conclusions.3 They recommend 1) routine screening for subclinical thyroid disease in the general population; 2) routine screening for subclinical thyroid disease in women who are pregnant or planning pregnancy; and 3) routine treatment of patients with subclinical hypothyroidism with serum TSH levels of 4.5–10 mU/liter.3 So what guidelines do we follow to help us with making a diagnosis and initiation of treatment?

As an ND, it is important to take into consideration the age of the patient, their signs and symptoms, and serum TSH levels in the upper limit when evaluating an individual for thyroid dysfunction. The thyroid affects every cell in the body and it is difficult to achieve optimum health without a properly functioning thyroid gland.

Laura Miller-Sickels, NMD attended Central Michigan University where she received her bachelor of science degree in psychology. While at Central Michigan, she was selected as a member of the Golden Key National Honor Society. Dr. Miller-Sickels continued her education in Tempe, Ariz. at SCNM, and graduated in 2005. Shortly thereafter, Dr. Miller-Sickels was certified in aesthetic treatments such as Botox, dermal fillers, laser treatments and skin rejuvenation.

Laura Miller-Sickels, NMD attended Central Michigan University where she received her bachelor of science degree in psychology. While at Central Michigan, she was selected as a member of the Golden Key National Honor Society. Dr. Miller-Sickels continued her education in Tempe, Ariz. at SCNM, and graduated in 2005. Shortly thereafter, Dr. Miller-Sickels was certified in aesthetic treatments such as Botox, dermal fillers, laser treatments and skin rejuvenation.

References

- World Population Ageing 2009. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. http://www.un.org/esa/population/publications/WPA2009/WPA2009_WorkingPaper.pdf. Updated December 2009. Accessed March 17, 2010.

- Woeber KA. Aging and the thyroid. West J Med. 1985;143(5):668-669.

- Ringel MD, Mazzaferri EL. Subclinical thyroid dysfunction–can there be a consensus about the consensus? J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(1):588-590.

- Canaris GJ, Manowitz NR, Mayor G, Ridgway EC. The Colorado thyroid disease prevalence study. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(4):526-534.

- Peeters RP. Thyroid hormones and aging. Hormones. 2008;7(1):28-35.

- Gussekloo J, van Exel E, de Craen AJ, Meinders AE, Frölich M, Westendorp RG. Thyroid status, disability and cognitive function, and survival in old age. JAMA. 2004;292(21):2591-2599.

- Hamilton TE, Davis S, Onstad L, Kopecky KJ. Thyrotropin levels in a population with no clinical, autoantibody, or ultrasonographic evidence of thyroid disease: implications for the diagnosis of subclinical hypothyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(4):1224-1230.