STEVEN RONDEAU, ND, BCIA-EEG

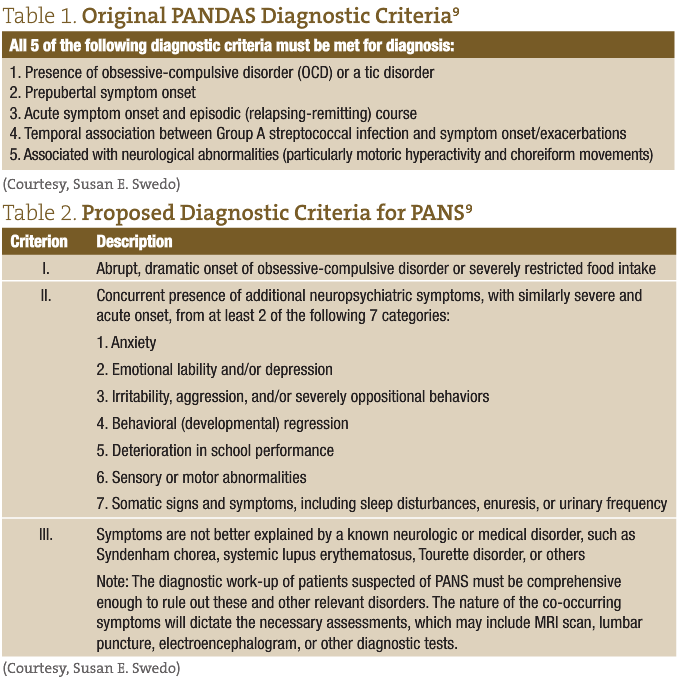

PANDAS is an acronym for “Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorder Associated with Streptococcus.” This condition, which was initially identified by Sue Swedo, MD and described in the American Journal of Psychiatry in 1998,1 is characterized by abrupt-onset obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and/or other neuropsychiatric symptoms in a child. (See Table 1 for Swedo’s original diagnostic criteria.) In my previous NDNR paper from 2010,2 I described the presentation, history and controversy surrounding this newly identified syndrome. Since that time, several other groups have sought to better redefine this condition, and the acronym, PANS, or Pediatric Acute-Onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome, was recently introduced.3,4 Prior to PANS, the acronym PITAND (Pediatric Infection-Triggered Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorder) had been suggested in the late 1990s after researchers hypothesized that there were more triggers beyond just Group A beta-hemolytic Streptococcus.5 In 2012, Dr Harvey Singer and his group proposed yet another description of acute-onset behavioral symptoms in children: Childhood Acute Neuropsychiatric Symptoms (CANS). These new acronyms were all conceived to include all other abrupt-onset OCD or tic symptoms— not just those brought on by streptococcal infections but also including newly reported behaviors such as abrupt-onset restrictive eating and anorexia, as well as verbal and motor tics. Additionally, these broader definitions were proposed to include other infectious agents as triggers for the condition, such as viruses (eg, influenza and Varicella), Mycoplasma, and Borrelia, to name a few. This may be due in part to the approximately 190 peer reviewed, indexed papers on PANDAS and its derivatives on PubMed, or to an explosion in cases seen in clinics worldwide. Whatever the reasons, the medical community today generally agrees that this is a real condition, despite the fact that that there is still no agreed-upon diagnostic criteria after more than a decade, nor a diagnostic code for insurance reimbursement. In addition to the lack of clear diagnostic criteria, there is still uncertainty in the areas of prevention, initial work-up, and standard-of-care protocols. In Table 2, the new proposed criteria are outlined for the more recently proposed PANS, the term most commonly referred to now among specialists.

While some work in the area has confused the picture and divided groups, others are working to clarify early research on PANDAS. A recent Italian study from 2013 provides a descriptive analysis of PANDAS and treatment outcomes.6 The summary of their findings is consistent what many of us see clinically: most PANDAS cases occur in boys, approximately 6 years old; the patients have elevated Strep antibody titers; and more than 75% respond positively to penicillin.5 Other important research by Kirvan et al has helped shed light on possible mechanisms, as well as unique antibodies which we can now test and quantify.7,8 Currently a multi-site, placebo-controlled trial is underway, conducted by Drs Swedo, Leckman, and Cunningham of the University of Oklahoma and testing the clinical application of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) in children with PANDAS.

Testing

Although the term “autoimmune” has been removed from the newer acronyms, autoimmunity is still a suspected mechanism. The names have been changed simply to de-emphasize the etiological agent. Dr Cunningham and her group at the University of Oklahoma have been working to explain possible mechanisms in their 2006 paper, “Antibody-mediated neuronal cell signaling in behavior and movement disorders.”7 In this paper they describe several unique markers (eg, CaM kinase II and G1cNAc) in children with these syndromes, which are not present in children with similar conditions such as Tourette’s syndrome (TS) and childhood obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), that are not commonly thought to be regulated by the immune system. A commercially available test developed from this research is commonly referred to as the Cunningham panel, or “the PANDAS test.” However, this testing method does not come without drawbacks. Firstly, insurance does not always cover it, which can pose an obstacle for patients. Secondly, the test rates a likelihood scale, as opposed to providing a definitive positive or negative result. Lastly, several of our patients have tested “PANDAS unlikely,” yet have responded positively to immune treatments. In a personal discussion with Dr Cunningham and her colleagues, they offered one possible explanation. They propose that there are more unique antibodies involved than what is currently offered with their test. Additionally, they are currently looking at other immune markers that may explain why some kids test “unlikely” yet respond favorably to treatments. For these reasons, this type of testing can be a difficult decision for families and physicians alike. For example, if a child were to test negative, that family may find it difficult to justify and pursue immunological treatments.

To view a sample report please visit this link: Rondeau_April_2014_Web File Report

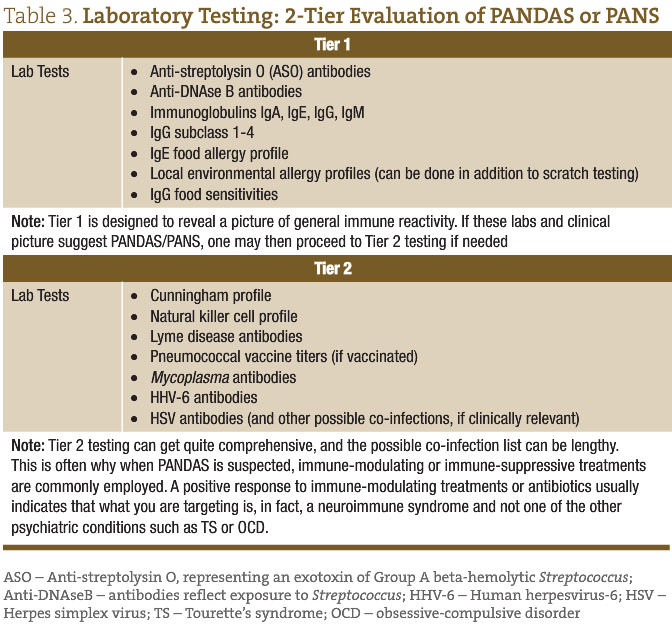

As part of the diagnostic criteria for PANDAS/PANS, other relevant disorders must be ruled out. Examples include metabolic disorders, seizures, Sydenham’s chorea and other autoimmune disorders, part of a comprehensive list found in Dr Singer’s article, “Moving from PANDAS to CANS.”3 Assuming these conditions have been ruled out and PANDAS or PANS is a consideration, the tests in Table 3 may be considered. These tests offer a starting place and are broken down into 2 tiers, based on our clinical evaluation of hundreds of suspected cases, though may need to be modified to each specific individual and his or her unique history.

Treatment

Part of the challenge of working with neuroimmune conditions like PANS is that the outcome of the treatment is often what verifies or provides the diagnosis. Therefore, targeting the abnormal immune response, infectious agent, and supporting the susceptible host tends to be the foundation of our holistic approach. Once we have verified that a neuroimmune condition is what we are targeting, complementary or supportive therapies such as diet, herbs, supplements and IV infusions can be started.

Targeting Infectious Agents

One first has to know what they are treating, however, which may not always be a bacterium or a virus (as was discovered in one of our recent patients who had elevated IgE levels of >1500, suspected parasite infection, and responded to positively to metronidazole). A short burst of steroids to quell the abnormal immune response and antibiotics to eradicate the infection are combined to create a common starting place if the suspected trigger is Strep or other bacterial trigger. Based on published studies and clinical experience, injectable penicillin, azithromycin, or amoxicillin and clavulanic acid (including XR versions) are reasonable starting medications.1,6 Oftentimes, a typical course of 5-10 days for common childhood Strep throat is not sufficient for a child with PANS, who may require 2-4 weeks of treatment. Although each case is unique, many kids would not have had symptoms resolved had it not been for either a longer course or higher dose of antibiotic than what is typical for that infectious agent.

Antiviral medications and herbal formulas can be useful if the infectious agent or laboratory picture points to a possible viral contribution. As mentioned earlier, there are times where anti-parasitic agents can be useful as well.

Immune Modulation

Additionally, immune-modulating treatments such as intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) may be considered later in the plan if there is evidence of an immune disorder that often has a favorable outcome with such a therapy, eg, a selective immune deficiency or an inadequate response to a vaccine such as pneumococcal vaccine (in a vaccinated child). I cannot stress enough how important dietary work is with all of our patients with tics, OCD, and/or anxiety; these conditions often respond well to a decrease in immune stimulation. For example, we have observed that a greater than usual number of kids with TS, tics, OCD, and/or PANS respond positively to an elimination of peanuts from their diet, with a gold standard reintroduction, for confirmation. Like with many autoimmune disorders, anti-inflammatories such as steroids and NSAIDS are commonly prescribed for PANS. Typically, a short burst will produce improvements in symptoms within only a few days.

We will often follow immune-modulating treatments and anti-inflammatories with frequent doses of curcumin to prolong the anti-inflammatory effect. This seems to extend the time between flare ups. To round out treatment plans and support the “susceptible host” we may also use IV infusion therapies such as a Myers cocktail or single nutrients such as high doses of IV vitamin C or glutathione. IV glutathione can produce very quick positive responses in patients depleted of this important immune staple.

Gastrointestinal Support

To protect the integrity of the gastrointestinal lining while using NSAIDS, we will often suggest probiotics throughout the entire treatment period. This is additionally helpful with concurrent antibiotics, as these can alter the microbiome, important for immune function and disease prevention.

Other Considerations

In differentiating between PANS and common childhood conditions (eg, TS and OCD), we commonly view tics, OCD, and anxiety, in general, as immune-influenced disease processes. This explains the predictable positive response to dietary changes. Other explanations that should be ruled out include inappropriate school placement, home stress, or environmental influences such as toxins or allergens; other possible explanations for tics can also often be revealed using imaging such as MRI or CT scans. If a child presents on a stimulant medication, we will often discontinue this, as stimulants can provoke and exacerbate many of the symptoms described as PANS. A common ADHD medication that can often improve symptoms presenting like PANS is guanfacine. Selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are often prescribed when kids present with PANS-like symptoms by psychiatrists unfamiliar with this condition. This can present quite a problem for kids and providers, as some, though not all, kids with PANS have reportedly worsened on SSRIs. Behavioral approaches such as “Habit Reversal Training” is rapidly gaining ground. Additionally, nutrients and supplements commonly used in these conditions are magnesium (300-800 mg/day); inositol (4 g BID-QID); 5-HTP (100-300 mg QD); NAC (1200-1800 mg/day). These suggestions can serve as a general starting place for kids with suspected PANS or tic disorders, alike, while waiting on laboratory results.

Conclusion

What seems apparent to myself and our team and other PANS specialists is that in a subgroup of children, their brains are highly reactive and respond inappropriately to auto-antibodies, unique infections, food, or other factors. These children then mount an immune response to foreign invaders, which triggers behavioral and/or motor symptoms. Despite the fact that this disorder is often viewed or reported as rare, it is seemingly much more common than is diagnosed. Perhaps, again, this is because of broader definitions that now include other triggers beyond Strep. In our group’s testimony to the state of Connecticut in 2013, advocating for insurance reimbursement and recognition of this condition, we conservatively estimated that approximately 162 000 US children, or 1-2% of all school aged children, suffer from this condition. Comparing that number to the approximately 32 000 cases of all childhood cancers and about 215 000 cases of type 1 and 2 diabetes combined in people 20 years and younger (representing less than 1% of that age group), one can see what a significant problem we have with identifying and properly treating our children suffering from PANS.

The idea that mental disorders could be triggered by an abnormal immune response is not new, yet its acceptance continues to be met with a surprising reluctance nearly 2 decades after it was first discovered. Dorris Rapp, MD, was discussing this phenomenon in her 1992 book, Is This Your Child?10 Clearly, we must continue to ask more questions and explore further research in the connection between the nervous system and the immune system. However, while we wait for unified diagnostic criteria, we can continue to evaluate safe and effective treatment options and individualized treatment plans based on clinical case reports and what we have learned from similar conditions. Much like anything in medicine, the futility of a one-size-fits-all approach has never been more apparent than with this syndrome.

Case Study

10-year-old male

Chief Complaint: Tics and OCD

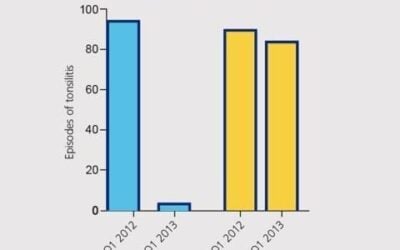

Relevant History: Recurrent sinus infections from 1 to 4 years old; single bout of croup; antibiotics for various infections and trips to ER; tonsillectomy/adenoidectomy at 2 years old

Symptoms: Started with obsession and then moved to motor tics. His symptoms worsened after a sore throat 2 years ago. Amoxicillin was given for sore throat, but it didn’t help and he quickly developed crying at school and obsessive thoughts. His pediatrician said it could not be PANDAS because throat culture was negative. He was then referred to a psychiatrist, who said “possible PANDAS” but diagnosed him with OCD and prescribed SSRIs. At this point, he came to Wholeness Center.

Work up: Ferritin; Total IgG/A/M/E; CRP; CBC; CMP; ASO titers; IgG subclasses 1-4; Mycoplasma IgG/IgM; S pneumonia IgG serotypes (14); Anti-DNase B antibodies; IgG food sensitivity panel

Remarkable lab findings: ASO 190 (H); Anti-DNase B 289 (H); 30+ IgG reactive foods

Treatment: Prednisone (30 mg PO QD x 5 days); IM penicillin G (2.5 million units in office); Probiotics; Curcumin (600 mg BID)

Follow up:

1 week later – Improved ability to write in school; fewer motor tics and intrusive thoughts; anxiety resolved and people outside of home commenting on changes and improvements

5 weeks later – Was sick recently and symptoms returned. Added a nutritional/herbal immune support formula (1 cap TID)

Steven Rondeau, ND, BCIA-EEG currently practices in Fort Collins, Colorado as part of a collaborative team at Wholeness Center. He graduated from SCNM and then continued his specialty training in developmental disorders and pediatrics in Utah before settling in northern Colorado. His focus is on the recovery of children with neurodevelopment disorders and psychiatric illness, using a combination of conventional and alternative therapies. He is a Defeat Autism Now (DAN!)-registered doctor and a Medical Academy of Pediatric Special Needs MAPS doctor, and currently serves on the medical advisory board for the PANDAS Resource Network. In addition, he is BCIA-EEG-certified in EEG biofeedback, neurofeedback, and quantitative EEG analysis.

Steven Rondeau, ND, BCIA-EEG currently practices in Fort Collins, Colorado as part of a collaborative team at Wholeness Center. He graduated from SCNM and then continued his specialty training in developmental disorders and pediatrics in Utah before settling in northern Colorado. His focus is on the recovery of children with neurodevelopment disorders and psychiatric illness, using a combination of conventional and alternative therapies. He is a Defeat Autism Now (DAN!)-registered doctor and a Medical Academy of Pediatric Special Needs MAPS doctor, and currently serves on the medical advisory board for the PANDAS Resource Network. In addition, he is BCIA-EEG-certified in EEG biofeedback, neurofeedback, and quantitative EEG analysis.

References

- Swedo SE, Leonard HL, Garvey M, et al. Pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections: clinical description of the first 50 cases. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155(2):264-271.

- Rondeau S. PANDAS: An Immune-Mediated Mental Illness. NDNR. 2010;6(12). https://ndnr.com/autoimmuneallergy-medicine/pandas-an-immune-mediated-mental-illness/

- Singer HS, Gilbert DL, Wolf DS, et al. Moving from PANDAS to CANS. J Pediatr. 2012;160(5):725-731.

- Macerollo A, Martino D. Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorders Associated with Streptococcal Infections (PANDAS): An Evolving Concept. Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov (N Y). 2013 Sep 25;3. tre-03-167-4158-7.

- Allen AJ, Leonard HL, Swedo SE. Case study: a new infection-triggered, autoimmune subtype of pediatric OCD and Tourette’s syndrome. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995;34(3):307-311.

- Falcini F, Lepri G, Rigante D, et al. -FINAL-2252: Descriptive analysis of pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorder associated with streptococcus infection (PANDAS) in a cohort of 65 Italian patients. Pediatr Rheumatol. 2013;11(Suppl 2):P242.

- Kirvan CA, Swedo SE, Snider LA, Cunningham MW. Antibody-mediated neuronal cell signaling in behavior and movement disorders. J Neuroimmunol. 2006;179(1-2):173-179.

- Kirvan CA, Swedo SE, Heuser JS, Cunningham MW. Mimicry and autoantibody-mediated neuronal cell signaling in Sydenham chorea. Nat Med. 2003;9(7):914-920.

- Swedo SE, Leckman JF, Rose NR. From Research Subgroup to Clinical Syndrome: Modifying the PANDAS Criteria to Describe PANS (Pediatric Acute-onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome). Pediatr Therapeut. 2012;12:113. OMICS Group Web site. http://www.omicsonline.org/from-research-subgroup-to-clinical-syndrome-modifying-the-pandas-criteria-to-describe-pans-pediatric-acute-onset-neuropsychiatric-syndrome-2161-0665.1000113.php?aid=4020. Accessed January 15, 2014.

- Rapp D. Is This Your Child? New York, NY: William Morrow Paperbacks; 1992.