Sussanna Czeranko, ND, BBE

Nature Cure Clinical Pearls

There Is Nothing Like A Fast

The value of fasting as a curative agent is mainly two-fold: first it purifies the system by increasing the activity of all the eliminating organs, and secondly, it gives a complete rest to the digestive and assimilative organs. During rest the body repairs itself. – R Moershell, DO, 1916, p.106

Almost every variation of disease has been permanently cured by rational fasting and diet; … these measures to assist the body to eliminate accumulated wastes and disease products, to rest depleted organs and to correct defective nutrition. – William F Havard, ND, 1920, p.277

Building of tissue―assimilation―takes place as the result of food correctly ingested and digested, but health depends upon a balance between nutrition and elimination. There is no eliminative agency known to science comparable with a properly administered fast―a scientific fast, if you will. – Dr Linda Burfield Hazzard, 1924, p.918

The attention the early Naturopaths gave to “the fast” could fill volumes. Not surprisingly, fasting as a healing measure did not escape Benedict Lust‘s radar. His publication, The Naturopath and Herald of Health, has a bounty of fasting articles enabling me to assemble a thick file. The fast was considered by many to be a cure-all and received accolades with claims bordering on the miraculous. One would not suspect much ado with the conducting of a simple fast: the patient abstains from eating and drinks water. Surprisingly, though, the literature shows that there was nothing simple about fasting. In fact, there were numerous ways to implement a fast. Let us consider a few of these methodologies and their benefactors. The abundance of material about fasting is a blessing, but also unfortunate because we will only be able to review highlights and key patterns in this remarkable modality.

Last month, Arnold Ehret’s fasting theories and system were presented. As you peruse the mélange of fasting systems reviewed below, you will realize that Ehret left his fingerprints upon the broad range and depth of the “Naturopathic fast.” Ehret’s book, Rational Fasting and Regeneration Diet, established a standard to which others have adhered. There were other books written, such as The Philosophy of Fasting, by the charismatic Edward E Purinton, and Vitality, Fasting and Nutrition, by Hereward Carrington. These 2 titles became the prominent textbooks for early naturopaths exploring fasting.

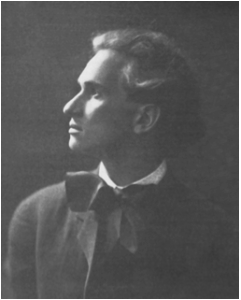

Edward Earle Purinton

Edward Purinton wrote prolifically and contributed many articles to Lust’s publications. His book on fasting does not fail to entertain the reader. Purinton had the gift of gab and his articles can be long-winded and poetic. His writing reflects a playful and loquacious nature and he is not shy to voice his opinion as unquestioned truth. His book was touted in The Naturopath as one of the principle publications on fasting, although the author himself contends, “In [this] book, The Philosophy of Fasting, you will find very much more about Life than about Fasting.” (Purinton, 1905, p.256) Purinton loved language and his coquettish use of it often generates witty statements that are sometimes awkward to absorb. For example, he declares: “To be sanitary is not necessarily to be sane. … Overeating is the commonest cause of starvation.” (Purinton, 1905, p.256) Purinton loved idioms with a clever twist and entertaining impact.

Purinton’s Prose

Today, we may find Purinton’s language eccentric; however, his contemporaries adored his writings. Dr C W Young, for example, an Osteopath from St. Paul, Minnesota, recognized in Purinton a kindred spirit. Young reviewed Purinton’s book, writing, “[Purinton’s] literary style is superior to that of all other writers on the new methods to maintain health and cure disease … He is lucid and clear, and free from pedantry.” (Young, 1906, p.235) In Young’s 3-page review, there is no mention of fasting; rather, he comments upon Purinton’s views of life.

A Couple Fasting Rules

One chapter in Purinton’s book that he had also submitted to Lust’s journal does contribute valuable material to the subject of fasting. “Twenty Rules of Sane Fasting” offers guidelines that address common mistakes and provide helpful tips. Rule 9, for example, states: “Keep near Nature,” and Rule 11 states, “The week preceding the Fast, let your diet be wholly laxative.” (Purinton, 1915, p.680) Purinton’s rules have a strong resemblance to those that in Ehret’s fasting guidelines. As a case in point, Ehret counseled fasters to drink lemon added to water to facilitate elimination. Purinton also makes the same recommendation: “Acid fruit juice cannot be surpassed as an aid to elimination; about a half a glass for the 24 hours [in] perhaps three times its bulk of water. Orange juice is best, with lemon juice close second.” (Purinton, 1916, pp.220–221) Another Ehret fasting tip reiterated by Purinton was the need to “devote the first three days to special elimination.” (Purinton, 1916, p.220)

R Moershell

In the April 1916 issue, Lust established a new department with its own column called “Naturopathic Therapeutics,” edited by R Moershell. Two months prior, Moershell had written an initial article, “The Fast,” that became a series of 4 on the subject. Moershell offered his guidelines for fasting. Undeniably, water was central to fasting according to Moershell, who writes, “Water is one of the important elements for a successful fast, and should be drunk at intervals of one hour during the first and second days, [and] every two hours thereafter.” (Moershell, 1916, p.105) Unlike Ehret, who counseled on drinking only when guided by thirst, Moershell had his patients drink water by a schedule, and a lot of it. He emphasized drinking cold water throughout the day except in the morning, at noon, and before retiring. The digestive tract over the course of the night accumulates mucus and he counsels readers to drink 2 cups of the hottest water that can be tolerated each morning to eliminate the harbored mucus. (Moershell, 1916, p.105) As we read through Moershell’s list, the properties of water are indeed comprehensive: “Dilutes and dissolves the poisonous elements, stimulates the circulation, flushes the blood stream causing the capillaries to dilate and suffusing the skin with blood causing a free perspiration, removes accumulation of gas, cleanses the stomach of bile.” (Moershell, 1916, p.105)

Physical Exercise

Another requirement during the fast is the inclusion of physical exercise. Moershell recommended any exercise “that act[s] as a stimulant to the circulation.” (Moershell, 1916, p.252) Calisthenics and walking were the very best forms of exercise. He writes, “Walking exercises every muscle in the body stimulat[ing] the circulation, heart and lungs.” (Moershell, 1916, p.252) His fondness for hot water consumption on rising and during the morning exercise routine was mighty intense and not for the faint of heart. The typical fasting routine involved drinking 1 to 2 very hot cups of water, followed by a few sit-ups and then 5 to 10 leg raises. “After these two movements, take about 10 deep inhalations. Drink two more cupfuls of hot water and then stationary running and skipping rope for a few minutes.” (Moershell, 1916, p.252) This exercise routine and periodic drinking continued until 1 to 2 quarts of water had been drunk and could be used even when not fasting.

After the morning exercises, Moershell advised a dry friction rub, followed by “a quick cold rub [using] a dripping towel.” (Moershell, 1916, p.252) “The friction [rub] bath will remove all the dead cells … that has collected on the surface of the skin, but of greater importance is the fact that this friction paves the way for the cold rub.” (Moershell, 1916, pp.252–253) A rough towel or a scrub brush was used for the friction bath.

Sun Bath and Air Bath

Other baths endorsed by the early naturopaths were the Sun Bath and the Air Bath. Sun and air bathing implied taking these baths in Nature, unclothed. If one did not have a private place, Moershell has the following advice: “A sun and air bath parlor can be easily made by hanging some sheets on four crossed wires, or by simply pinning a blanket on a wire so as to screen the yard from the street.” (Moershell, 1916, p.392) Taking walks throughout the day was paramount to a fast. Moershell encouraged his readers to walk wearing as little clothing and, if possible, naked. As many of us do not have the luxury of living in uninhabited places, walking naked may be quite impossible to accomplish in most communities where such behavior is eschewed. Another point made in this taxonomy of suggestions was that exercise was only good if fatigue was not the result. His advice: “Discretion should be used; too much activity will tend to waste the vitality, break down too much tissue, thus weakening instead of building strength.” (Moershell, 1916, p.322) A little bit of exercise was good, but excessive activity was bad.

The Good and Bad Attitude

The good and bad also applied to the faster’s mental attitude. He writes, “A mental equanimity must be maintained under all circumstances, if possible; most of the benefit derived from the fast depends upon this fact.” (Moershell, 1916, p.322) Negative thoughts were detrimental to health and were to be banished without hesitation. He continues, “Every negative thought creates poison.” (Moershell, 1916, p.322) He defined negative thoughts as anything aroused by “anger, hate, jealousy, discouragement, envy, passion, pessimism, fear, worry, selfishness, and thinking evil.” (Moershell, 1916, p.322) Thoughts had power and this concept was well understood by Moershell. He writes, “Try to indulge in positive, good or right thinking, be optimistic, think evil of no one, [and] love your neighbor as yourself, for love is the fulfilling of the law, and is the new commandment.” (Moershell, 1916, pp.323–324)

Rest and Relax

Another element of the fast was relaxation and rest. In the area of rest, Moershell had definite guidelines: “Retire between nine and ten PM, and never later than ten o’clock; try to get at least nine hours of repose.” (Moershell, 1916, p.322)

Breaking the Fast

Breaking the fast correctly was most crucial in determining its success. Here, Moershell offers some caution that, even before undertaking a fast, one must be resolved to have willpower to govern appetite. At the end of a fast, “there will be an incessant craving, a ravenous desire to stuff.” (Moershell, 1916, p.393) Willpower was absolutely necessary to not gorge on food at the end of a fast. Moershell recommended that his patients follow the water fast with a milk diet or a fruit diet for a number of weeks. Milk was never endorsed by Ehret, although Moershell incorporated the milk diet in his fasting regime.

Moershell had very specific instructions on how to break a fast that was not over 6 days in length. On the designated day, one was to drink 2 cups of hot water in the morning and “a half an hour later take about three or four tablespoonfuls of grape juice, orange or fresh apple juice. … Continue this amount of juice every three or four hours the first day.” (Moershell, 1916, p.393) On the second day, drinking juices was continued, the dose increasing to a half a wineglassful every 2 to 3 hours. “On the third day, a little juicy fruit may be eaten, masticating each mouthful thoroughly. Oranges, tangerines, pineapples and peaches are good fruits to use.” (Moershell, 1916, p.393) Moershell counseled his patients to consume fruit for a week and then, gradually in the second week, to add nuts and milk.

William Freeman Havard

William Havard taught at Henry Lindlahr’s school in Chicago in the early 1910’s. His contribution to the subject of fasting provided his colleagues with a no-nonsense logic. “The sick animal refuses food by instinct. Even domesticated animals, when sick, seek a quiet secluded retreat and rest, at the same time refusing to partake of food. Only man, the intellectual animal, persists in clinging to his daily habits after Nature has issued her warning [that] the disorder exists in the body.” (Havard, 1920, p.277) He wrote a concise and detailed article for Lust’s publication in July of 1920 that provided invaluable guidelines for his colleagues interested in conducting fasts in their practice. His first counsel: “Fasting is not advised unless the patient thoroughly understand his condition, or unless he is under the care of a competent physician.” (Havard, 1920, pp.277–278) Preparing adequately for a fast was essential for its success. Havard recommended “a raw vegetable diet for one or more days preceding the fast, during which time high enemas should be employed nightly.” (Havard, 1920, p.278)

William Havard taught at Henry Lindlahr’s school in Chicago in the early 1910’s. His contribution to the subject of fasting provided his colleagues with a no-nonsense logic. “The sick animal refuses food by instinct. Even domesticated animals, when sick, seek a quiet secluded retreat and rest, at the same time refusing to partake of food. Only man, the intellectual animal, persists in clinging to his daily habits after Nature has issued her warning [that] the disorder exists in the body.” (Havard, 1920, p.277) He wrote a concise and detailed article for Lust’s publication in July of 1920 that provided invaluable guidelines for his colleagues interested in conducting fasts in their practice. His first counsel: “Fasting is not advised unless the patient thoroughly understand his condition, or unless he is under the care of a competent physician.” (Havard, 1920, pp.277–278) Preparing adequately for a fast was essential for its success. Havard recommended “a raw vegetable diet for one or more days preceding the fast, during which time high enemas should be employed nightly.” (Havard, 1920, p.278)

The Purpose of the Fast

The purpose of the fast was to eliminate from the body its harbored burden. Bowel movements were critical and Havard considered that “the patient should have a movement of the bowels at least once in 24 hours, for the first seven days.” (Havard, 1920, p.278) Ehret’s mucus theories were re-iterated by Havard. He writes: “Mucous is continually being secreted from the membranes of the stomach and intestines and the liver will continue to throw off bile. If this material is not promptly removed, it will decompose and give rise to systemic poisoning through its reabsorption.” (Havard, 1920, p.278)

Water with Water

Havard also shared Ehret’s thoughts on water consumption. He writes, “It is an erroneous idea to believe that the faster should drink large quantities of water. The patient should take only enough to satisfy his thirst.” (Havard, 1920, p.278) Havard encouraged patients to exercise in the open air, and especially take long walks. He also recommended “a quick, cool friction bath … in the morning followed by a vigorous towel rub.” (Havard, 1920, p.278)

The duration of a fast ranged from 1 to 40 days. Havard’s guidelines for the length of a fast depended upon the reason for the fast. He explains:

If a fast is decreed for the purpose of curing digestive disorders, usually from three to ten days will be sufficient. In obese individuals … from 14 to 30 days is required to affect any marked change. … In constitutional disorders such as rheumatism, arthritis, syphilis, diabetes, Bright’s disease, etc, the fast may have to be continued up to 40 days.

(Havard, 1920, p.279)

Ending the Fast

Havard paid extra attention to the ending of fast because the lasting benefits were contingent upon this stage of the fast. Fasts lasting less than 3 to 4 days were “broken on fresh popcorn without butter or salt, about a double handful three times the first day, and ripe fruit. The second day the patient should eat fruit and well-cooked cereals, thinned with milk or cream, returning to the prescribed diet on the third day.” (Havard, 1920, p.279) Havard’s inclusion of cereals and dairy products departed from the Ehret protocol. For fasts exceeding 10 days, Havard cautioned that great care be taken to avoid bulky food and to eat a very small amount at a time. Havard writes, “Exercise care in breaking a fast, remembering that in many cases more harm than good will result from introducing too much food, or the wrong kind of food, after a fast.” (Havard, 1920, p.281)

Curating a Diet

After the fast, Havard recommended a curative diet to continue a curative outcome by creating a resting state for the digestive tract while enhancing the elimination process. Certain foods were banned, including meat, which “undergoes decomposition and putrefaction in the alimentary tract, thus generating a great quantity of poisons.” (Havard, 1920, p.281) Other foods were also banned: “Eggs, cheese, very starchy substances including white flour products, polished rice and starchy vegetables such as potatoes; refined sugar; stimulants―tea, coffee, tobacco, alcoholic beverages; seasoning such as pepper, spices, vinegar and condiments, must all be scratched from the list of permissible foods.” (Havard, 1920, p.281) Raw fresh fruits and vegetables aided elimination and composed the bulk of the “Eliminating Diet.” Acidic fruits such as citrus and pomegranates were stronger in their action on elimination than sweet fruits. “The vegetables which grow above the ground are superior to underground vegetables (roots and tubers) as eliminators.” (Havard, 1920, p.282) Nevertheless, roots and tubers such as turnips, black radish, and horse radish, grated and served in a leafy salad, were recommended as good intestinal cleansers and blood purifiers. (Havard, 1920, p.282)

Elimination Diet

Havard’s suggestions for an Elimination Diet resembled the work of Dr William Hay (1866–1940), who devised a food-combining diet in 1904 to cure himself of hypertension, Bright’s disease, and obesity. Both men advised against eating “fruits and vegetables at the same meal.” (Havard, 1920, p.283) Other features of the Elimination Diet advocated by Havard involved avoidance of boiling vegetables, which destroyed nutrients, and avoiding the use of sweeteners, salt, and seasoning. In addition, Havard advocated simplicity in the diet: “Do not eat more than two kinds of fruits at a meal nor more than three kinds of vegetables.” (Havard, 1920, p.282)

Fear of Starvation

Havard emphasized the harm that fear of starvation had on patients during fasting. It was no wonder that fear would be a factor to reckon with, since the allopathic community condemned the abstinence of eating in the sick. The old school ‘Regular’ adhered to the notion that only drugs can do anything for diseases and sick people needed to preserve their strength. What better way to do so, they argued, than by eating large meals. Havard writes, “The average Allopath is violently opposed to this method of cure, because he has the false impression that [fasting] impairs the patient’s vitality. He makes no discrimination between the food requirements of the healthy person and [the] invalid, unless it be that he thinks the person when sick requires even more food.” (Havard, 1920, p.278)

A House Divided

As in many aspects of naturopathy and allopathy, the divide between the 2 medical camps stretched impossibly wide on the topic of fasting. Fasting, as a healing practice, was misunderstood and outright rejected by the self-interested drug pushers who could not possibly conceptualize its benefits or necessity. Pharmaceuticals today continue to be the default strategy of the biomedicine profession in the treatment of illness and diseases, a fact that is all the more concerning in light of the inappropriate influence of the pharmaceutical industry on medical doctors and their treatment protocols. The scope of the conflict of interest is reflected in the high price paid for such promotional activity, which is reported to be $2.6 billion annually. Present day journalist Elizabeth Hayes reported, “Last year, 100 Oregon doctors received $9 million from drug manufacturers and medical device makers. (Hayes, 2016, p.16) In Portland, a single medical doctor received $133, 940 for his endorsements of a particular prostate drug in 2015. (Hayes, 2016, p.17)

Linda Burfield Hazzard, DO

Of the many promoters of fasting, Dr Linda Burfield Hazzard was “widely known as a prominent advocate and practitioner of fasting for the cure of disease and … met with a large measure of success in her chosen field.” (Hazzard, 1911, p.776) Natural doctors in the early 20th century who followed the fasting cure faced much discrimination and the medical fraternity did not waste any time to pounce upon a disciple of fasting when things went wrong. The name of Linda Burfield Hazzard became associated with irresponsible doctoring causing death from a fasting cure.

Of the many promoters of fasting, Dr Linda Burfield Hazzard was “widely known as a prominent advocate and practitioner of fasting for the cure of disease and … met with a large measure of success in her chosen field.” (Hazzard, 1911, p.776) Natural doctors in the early 20th century who followed the fasting cure faced much discrimination and the medical fraternity did not waste any time to pounce upon a disciple of fasting when things went wrong. The name of Linda Burfield Hazzard became associated with irresponsible doctoring causing death from a fasting cure.

Intestines of Infantile Size

The medical establishment did not spare any vituperative epitaphs for Hazzard and hounded her with their allegations. She gained much publicity because of the unfortunate deaths of some patients, and spent a considerable amount to defend herself against charges. Hazzard, an osteopath, looked at the autopsies of her patients and discerned that fasting could not have caused the anatomical destruction observed. “In all these years but twelve deaths have occurred under her care, and in each and every instance the post mortem examination revealed the cause as organic disease that made death inevitable, fasting or feeding.” (Hazzard, 1911, p.776) Autopsies showed “intestines of infantile size” which she argued “cannot be produced by a fast in a few days or weeks.” (Hazzard, 1911, p.788)

Hazzard studied under Dr Edward Hooker Dewey, who was one of the first to champion the fasting cure. She studied osteopathy and began her practice in Minneapolis, later moving to Seattle. Her decision to move to Washington was predicated on the state’s liberal laws recognizing natural healing. In Seattle, her practice grew and became lucrative, especially for a woman practicing osteopathy and prescribing fasting. In 1911, Benedict Lust publicized the difficulties that Dr Hazzard faced and appealed to the Naturopath’s readers to contribute to a legal fund for Hazzard.

The Long-Held Belief in Fasting

Fasting articles appeared in Benedict Lust’s The Naturopath and Herald of Health from the start. In 1902, “Aristophagy,” a title meaning the eating of the best, appeared in the February issue. Benedict Lust noted in his article that vegetarian restaurants were popping up in New York City and failing in their enterprise because of “slovenly service, bungling management, bald theories, inflexible fare, and [disgusting rather than attractive food].” (Lust, 1902, p.78) He noted another trend occurring at the time: “The fasting fad is the rage of the hour.” (Lust, 1902, p.78) Lust suggested that a proper fast had “six elements: instruction, conviction, gradation, adaptation, supplementation and transition.” (Lust, 1902, p.79) He cited 2 men and their books as providing “the first preparative to regenerative fasting, … Kuhne’s New Science of Healing, and Just’s Return to Nature.” (Lust, 1902, p.790)

Give the Stomach a Rest

The reasons for conducting a fast had an assortment of rationales. John Morgan wrote in 1903 about the merits of a fruit diet, much like Arnold Ehret. In Morgan’s view, fruit was alkaline and aided in the elimination of toxins. His straight forward advice to readers: “When the alimentary tract is clogged until the liver, pancreas and stomach glands cannot act, drink pure fresh country butter milk, pure grape juice and abstain from all food for 36 hours. This should be done once a week and the stomach given a rest.” (Morgan, 1903, p.255) The length of a fast was “until the body is purified so that the physical functions can control the living cells.” (Morgan, 1903, p.255)

Volumes of Material Speak for Itself

The sheer volume of material on fasting evident in the Lust journals reflected a strong adherence to its use and value. Carefully conducted fasting regimens were, in the view of our forebears, a valuable tool in their unending quest to find and teach habits and protocols in support of robust, enduring health.

[References]

Havard, W. F. (1920). Fasting. Herald of Health and Naturopath, XXV (6), 277–283.

Hayes, E. (2016). The money and influence in medicine. Portland Business Journal, 33(37).

Hazzard, L. B. (1911). Medical persecution of the fasting cure. The Naturopath and Herald of Health, XVI (12), 776–778.

Hazzard, L. B. (1924). Therapeutic fasting and its pioneers. Naturopath, XXIX (10), 915–921.

Lust, B. (1902). Aristophagy. The Naturopath and Herald of Health, III (2), 78–80.

Moershell, R. (1916). The fast. Herald of Health and Naturopath, XVI (2), 105–106.

Moershell, R. (1916). The fast [continuation]. Herald of Health and Naturopath, XVI (4), 252–253.

Moershell, R. (1916). The fast [continuation]. Herald of Health and Naturopath, XVI (5), 322–324.

Moershell, R. (1916). The fast [continuation]. Herald of Health and Naturopath, XVI (7), 392–393.

Morgan, J. F. (1903). Generative life forces. The Naturopath and Herald of Health, IV (9), 254–256.

Purinton, E. E. (1905). The philosophy of fasting. The Naturopath and Herald of Health, VI (9), 255–257.

Purinton, E. E. (1915). Twenty rules for sane fasting. The Naturopath and Herald of Health, XV (11), 674–680.

Purinton, E. E. (1916). Twenty rules for sane fasting. Herald of Health and Naturopath, XVI (4), 220–222.

Young, C. W. (1906). Review of Philosophy of Fasting. The Naturopath and Herald of Health, VII (6), 235–237.

Sussanna Czeranko ND, BBE, incorporates “nature-cure” approaches to primary care by including balneotherapy, breathing therapy, and nutrition into her naturopathic practice. Dr Czeranko is a faculty member working as the Rare Books curator at NCNM and is currently compiling a 12-volume series based upon Benedict Lust’s journals, published early in the last century. Her published books include: Origins of Naturopathic Medicine; Philosophy of Naturopathic Medicine; Dietetics of Naturopathic Medicine; Principles of Naturopathic Medicine; Vaccination and Naturopathic Medicine; and Physical Culture in Naturopathic Medicine. Dr Czeranko is the founder of the Breathing Academy, a training institute for naturopaths to incorporate a scientific model of breathing therapy called Buteyko into their practice. She is also a founding board member of the International Congress of Naturopathic Medicine and a member of the International Society of Medical Hydrology.

Sussanna Czeranko ND, BBE, incorporates “nature-cure” approaches to primary care by including balneotherapy, breathing therapy, and nutrition into her naturopathic practice. Dr Czeranko is a faculty member working as the Rare Books curator at NCNM and is currently compiling a 12-volume series based upon Benedict Lust’s journals, published early in the last century. Her published books include: Origins of Naturopathic Medicine; Philosophy of Naturopathic Medicine; Dietetics of Naturopathic Medicine; Principles of Naturopathic Medicine; Vaccination and Naturopathic Medicine; and Physical Culture in Naturopathic Medicine. Dr Czeranko is the founder of the Breathing Academy, a training institute for naturopaths to incorporate a scientific model of breathing therapy called Buteyko into their practice. She is also a founding board member of the International Congress of Naturopathic Medicine and a member of the International Society of Medical Hydrology.