Dan Carter, ND

Cayenne pepper (Capsicum annuum and Capsicum frutescens) has a notable history of use for cardiovascular disorders. One of the early pioneers using cayenne was Dr. John Christopher from Salt Lake City, Utah. Dr. Christopher was drafted into the Army during World War II and declared to his superiors that he was a conscientious objector. Because of his strong peaceful convictions he was sent to Fort Lewis, Wash., and was assigned to supervise the medical dispensary. He soon gained favor with the officer in charge by using herbs to successfully treat many skin infections that were refractory to pharmaceutical treatment. Because of this success he was given permission to practice herbology, and was the only practicing herbalist in the U.S. Army in World War II. Because of his own problems with hypertension, Dr. Christopher began working with cayenne and found that it restored the elasticity of the arteries, and corrected or prevented arteriosclerosis. He also found that it stabilized blood pressure and was powerful enough to stop a heart attack while in progress. After his Army service was completed he continued his studies, and in 1946 he graduated from the Institute of Drugless Therapy in Tama, Iowa. In later years, by using cayenne, he never lost a patient to a heart attack (Christopher, 1996).

Cayenne and Circulation

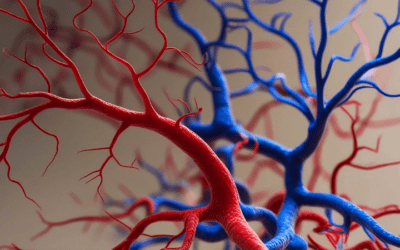

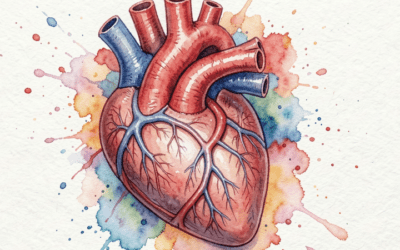

Research has provided a scientific basis for Dr. Christopher’s use of cayenne. Capsaicin (8-methyl-N-vanillyl-6-nonenamide) is the active component of cayenne pepper. Capsaicin inhibits platelet aggregation while avoiding interference with normal blood coagulation (Choi, 2000). Platelet aggregation contributes to arterial thrombosis after the disruption of vulnerable plaque, so platelet aggregation inhibitors such as aspirin or clopidogrel are often prescribed for patients with increased risk of myocardial infarct. Both aspirin and clopidogrel carry increased risk of serious bleeding (Medline Plus, n.d.). Unlike aspirin and clopidogrel, capsaicin decreases the danger of excessive bleeding. Studies in Japan showed that capsaicin stimulates sensory-afferent neurons and inhibits both bacterial growth and platelet aggregation. The later finding supports cayenne’s use in preventing thrombosis (Tsuchiya, 2001). Researchers in Pennsylvania studied the signaling mechanisms for the chest pain caused by myocardial ischemia and found that the VR1 capsaicin receptor is expressed on sensory nerve endings of the heart (Pan and Chen, 2004). Between the platelet aggregation inhibition and binding to cardiac capsaicin receptors, thrombi are inhibited and the pain subsides. Two studies showed that capsaicin evoked concentration-dependent relaxant responses in precontracted arteries (Gupta et al., 2007), and dilated and relaxed blood vessel walls (Takaki et al., 1994). Capsaicin can stimulate the vanilloid receptors in the brain, which release two neuropeptides, namely calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) and substance P. CGRP mediates the vasodilatation caused by capsaicin. The other active constituents of cayenne include vitamins A and C, carotenoids and volatile oils (Murray, 1995).

Safety and Toxicology

The Material Safety Data Sheet for capsaicin would most likely discourage any person not familiar with the parent product, cayenne, to avoid it altogether.

“Potential Acute Health Effects: Extremely hazardous in case of eye contact (irritant). Very hazardous in case of skin contact (irritant), of ingestion, of inhalation (lung irritant). Severe over-exposure can result in death. Inflammation of the eye is characterized by redness, watering and itching. Skin inflammation is characterized by itching, scaling, reddening or, occasionally, blistering” (ScienceLab, n.d.). The whole herb is apparently not as toxic.

A study published in Drug and Chemical Toxicology looked at the overdose potential of Tabasco sauce. They concluded that an average-weight person would need to consume almost a half-gallon of sauce to overdose and lose consciousness. In Mills and Bone, it was reported that investigations to determine the mutagenic and carcinogenic activity of capsaicin were contradictory. They also stated that more recent studies indicated that capsaicin demonstrated protective properties against some mutagens and chemical carcinogens (Mills and Bone, 2000).

Case Study

On September 27, 2007, I was performing a new patient intake in my office. I felt a sudden intense epigastric pain and, thinking it was heartburn, went on with the interview. The symptom did not pass and was joined by a related symptom of pain in the left side of my mandible and slight light-headedness. “Well,” I thought, “I think I might be having a heart attack.”

I excused myself from the interview and went to my supplement room, where I took an oral dose of four 500mg cayenne capsules. I returned to the interview for another few minutes, but the symptoms were not resolving. I told the patient that I might be having a heart problem and needed to take some medicine. He asked if he should call 911. I said no, and drew about 10 ounces of warm water from the tap, then emptied and mixed eight cayenne capsules into the water. I am known for enjoying spicy food and so drank the mixture down without hesitation; it was quite pungent! I returned to the patient and he agreed to sit with me. Within two or three minutes of drinking the cayenne mixture, the symptoms started to resolve, and within ten minutes they were gone.

We often hear about fear and feelings of doom when people experience sudden heart problems. My thoughts were a little different; there was no fear, just concern about leaving the interview half done. I also had a full bladder and was concerned that if I lost consciousness or died I would most likely wet myself (the odd musings of a doctor who thinks he may die!). The patient agreed to return on a more auspicious day.

I called several cardiologists to see if they would perform an evaluation, but all of them wanted me to go to the emergency room. I declined, and instead went to the hospital laboratory, where I had an ECG and blood drawn for CK, CKMB and cardiac troponins. The ECG was normal, which was very encouraging. I took the rest of the day off and relaxed, continuing with two cayenne capsules every two hours. The following day at 24 hours post cardiac symptoms, I repeated the blood tests and added a CRP. All of the blood tests returned normal values, so my conclusion was that prompt treatment prevented any myocardial damage. The only side effects from the high doses of cayenne were minor gastrointestinal rumbling and diarrhea, which resolved within a day. I did consult with a colleague and started on a more comprehensive prevention program.

Dan Carter, ND, graduated from NCNM in 1994 and completed a two-year family practice residency at the college. He was appointed to a full-time faculty position in 1997 and set up the teaching clinic’s IV therapy clinical practicum the following year. He also established an environmental medicine program in the school’s clinic. Dr. Carter is an instructor for IV nutritional therapy for physicians seminars, teaching since 1991. The workshops provide complete training to physicians internationally for the safe and effective use of IV nutrient therapies. Dr. Carter is also certified by ACAM to administer chelation therapy.

References

Christopher JR: School of Natural Healing (20th Anniversary ed), Provo, 1996, Christopher Publications, pp. iv.-vii.

Choi SY: Capsaicin inhibits platelet-activating factor-induced cytosolic Ca2+ rise and superoxide production, J Immunol Oct 1;165(7):3992-8, 2000.

Medline Plus/National Institutes of Health: www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/druginfo/medmaster/a601040.html

Medline Plus/National Institutes of Health: www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/druginfo/medmaster/a682878.html

Tsuchiya H: Biphasic membrane effects of capsaicin, an active component in Capsicum species, J Ethnopharmacol Aug;76(3):313, 2001.

Pan, H-L and Chen, S-R: Sensing tissue ischemia: another new function for capsaicin receptors?, Circulation 110:1826-1831, 2004.

Gupta S et al: Pharmacological characterisation of capsaicin-induced relaxations in human and porcine isolated arteries, Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol Mar;375(1):29-38, 2007.

Takaki M et al: Effects of capsaicin on mechanoenergetics of excised cross-circulated canine left ventricle and coronary artery, J Mol Cell Cardiol Sep;26(9):1227-39, 1994.

Mitchell JA et al: Role of nitric oxide in the dilator actions of capsaicin-sensitive nerves in the rabbit coronary circulation, Neuropeptides Aug;31(4):333-8, 1997.

Murray M: The Healing Power of Herbs (2nd ed), Roseville, 1995, Prima Publishing, p. 71.

ScienceLab: www.sciencelab.com/xMSDS-Capsaicin_Natural-9923296.

Mills S and Bone K: Principles and Practice of Phytotherapy, New York, 2000, Churchill Livingston, p. 43.