Dan Carter, ND

This article offers a succinct review of atrial fibrillation (AF). It also presents approaches to decrease the risk factors and to treat AF by nonpharmaceutical means.

This article offers a succinct review of atrial fibrillation (AF). It also presents approaches to decrease the risk factors and to treat AF by nonpharmaceutical means.

Atrial fibrillation is caused by a malfunction in the heart’s electrical system and is the most common cardiac arrhythmia. By age 80 years, average lifetime risks for AF are 22.7% (range, 20.1%-24.1%) in men and 21.6% (range, 19.3%-22.7%) in women.1 Among individuals without prior or concurrent congestive heart failure or myocardial infarction who developed AF, the lifetime risk for AF was approximately 16%. Its incidence and prevalence increase with age and with the presence of structural heart disease. Pharmacotherapy for rate or rhythm control typically fails over time, so research interests are being centered on ablation procedures. Bleeding risks associated with anticoagulation are significant, so management of patients with AF needs to be individualized.2

Risk Factors for AF

Age

Risk of developing AF increases with age, and this age-specific prevalence is higher among men than among women.3 Emerging evidence supports that lower androgen levels predict poor cardiovascular risk profile.4

Heart Disease

The most common coronary issues associated with AF include valve problems, history of myocardial infarction, and heart surgery. Most AF is caused by ischemic heart disease.5

Hypertension

Another risk factor for AF is hypertension. Hypertension that is not well controlled with lifestyle changes or medications increases the risk of AF.

Chronic Diseases

Increased risk of AF is associated with the following chronic diseases: hyperthyroidism, sleep apnea, chronic lung disease, pulmonary embolism, congenital heart disease, pericarditis, viral infection, and other medical problems.

Alcohol Intoxication

Drinking too much alcohol too quickly can trigger an episode of AF in some individuals. Binge drinking (5 drinks in 2 hours for men or 4 drinks for women) increases this risk.

Family History

A final risk factor is family history. Increased risk of AF occurs in some families with a history of the disorder.

Diagnosis and Evaluation

History and physical examination are required to define the following6: (1) The nature and presence of AF-associated symptoms. (2) A clinical description of the AF (ie, first episode, paroxysmal, persistent, or permanent). Paroxysmal AF episodes terminate spontaneously within 7 days, with most episodes lasting less than 24 hours. Persistent AF episodes last longer than 7 days and may require pharmacologic or electrical intervention to terminate. Permanent AF has persisted for longer than 1 year because cardioversion has failed or has not been attempted. (3) The date of the first symptomatic attack. (4) Precipitating factors, duration, frequency, and mode of termination of AF. (5) Pharmacologic treatments and response. (6) Underlying heart disease or treatable conditions (eg, alcohol consumption and hyperthyroidism).

Electrocardiography is useful to verify AF and to assess wave intervals, other arrhythmias, the presence of prior myocardial infarction, left ventricular hypertrophy, and bundle branch block. Minimal blood testing includes a comprehensive metabolic panel to evaluate hepatic and renal function and a thyroid panel.

Additional testing may be necessary, including the following: (1) Exercise testing may be needed to assess questionable rate control (as in permanent AF), to reproduce exercise-induced AF, and to exclude ischemia before selecting antiarrhythmic drugs. (2) Holter monitor recordings may help diagnose the type of arrhythmia if the diagnosis is in question and can help evaluate rate control.

Allopathic Treatment

Allopathic treatments of AF center on pharmacologic cardioversion, transthoracic direct current shock if drugs are not effective, drugs to maintain sinus rhythm, and antithrombotic therapy to decrease the risk of stroke, pulmonary embolism, and myocardial infarction. Fitzmaurice7 suggests that electrical cardioversion should no longer be offered routinely to patients with AF. The clinical situations where it may be useful include patients who are seen acutely within 24 hours of onset of AF or patients who are symptomatic despite medical therapy.

The drugs used for cardioversion and rhythm control are rife with adverse effects but may be necessary until nutritional intervention can have an effect. A typical adverse effects profile is that of amiodarone. Its adverse effects include pulmonary toxicity, polyneuropathy, photosensitivity, bradycardia, hepatic toxicity, thyroid dysfunction, eye complications, gastrointestinal upset, and torsades de pointes.8

Compromised hemodynamics in the atria can lead to increased risk of thrombus formation, stroke, and myocardial infarction. Warfarin sodium is the anticoagulant of choice for AF. Bleeding is the primary adverse effect of warfarin and is related to the intensity of anticoagulation, length of therapy, the patient’s underlying disease state, and the use of other drugs that may affect hemostasis or interfere with metabolism of warfarin. Fatal or nonfatal hemorrhage may occur from any tissue or organ during anticoagulant therapy.9 Dabigatran extexilate, a direct thrombin inhibitor, was approved in October 2010 by the Food and Drug Administration to treat patients with AF. Routine monitoring is not required, but an activated partial thromboplastin time more than 2.5-fold higher than the control level indicates overanticoagulation. A direct factor Xa inhibitor is rivaroxaban. On July 1, 2011, the Food and Drug Administration approved the use of rivaroxaban for prophylaxis of deep vein thrombosis (which may lead to pulmonary embolism) in adults undergoing hip and knee replacement surgery.10 These newer anticoagulants will be increasingly seen in clinical practice.

Naturopathic and Lifestyle Treatment

Home Treatment

Home treatments may be offered to diagnosed, treated, and established patients. A patient handout is best, recommending the following therapies:

- Take a deep breath and relax.

- Perform the Valsalva maneuver.

- Take a 30C dose of homeopathic Aconite (chest rubrics include palpitation and tachycardia).

- If there are no contraindications,11 perform carotid sinus massage.

- Call your physician if the AF continues.

Exercise

Patients can exercise if the activity does not induce AF episodes. With chronic AF, the heart rate is very rapid and decreases exercise capacity.

Diet

A whole-food organic diet12 (as much as is possible and practical) is preferred for patients with AF.

- Eat a sufficient amount of complete protein (½ g of protein per 1 lb of body weight). Include meats, eggs, and low-mercury seafood (cold-water fish, such as salmon, is especially beneficial). Raw dairy is recommended for those who tolerate it; whey protein is useful for smoothies.

- Eat raw and cooked vegetables and salad greens ad libitum.

- Choose as carbohydrate sources sweet potatoes, yams, white potatoes, and white rice. Unless the patient is an athlete, the daily intake should be limited to 150 g (preferably ≤100 g).

- Cook foods with chemically stable oils, such as coconut (best), butter, and palm kernel, and use olive oil on salads and foods after cooking.

- Avoid simple sugars and seed-derived edible oils (soy, corn, safflower, sunflower, and canola).

Supplements

The following supplements are recommended for patients with AF:

- Magnesium citrate malate (150 mg with meals 3 times daily and up to 300 mg at bedtime).13,14

- Taurine (1000 mg with meals 3 times daily and 2000 mg at bedtime).15,16

- Arginine (sustained release, 1000 mg twice daily).17

- l-carnitine (1000 mg twice daily).18,19

- Coenzyme Q10 (800 mg daily).

- Fish oil (up to 1500 mg of eicosapentaenoic/docosahexaenoic acid [EPA/DHA] daily with a meal).20

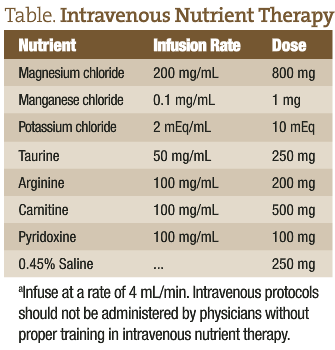

Physicians trained in intravenous nutrient therapy can use appropriate nutrients to achieve more rapid resolution of arrhythmias, such as AF. The following table presents an example of a safe and effective intravenous protocol for arrhythmias:

Case Reports

Case 1

A 56-year-old man had chronic AF, with onset at age 28 years. Known triggers are monosodium glutamate, dehydration, stress, alcohol, and nitrates. Typically, he has short episodes of AF weekly, controlled with low doses of digoxin. He had an extended episode of AF over the past weekend that was converted by intravenous quinidine. His family history is positive for heart disease; the patient is normotensive. He describes himself as athletic and enjoys outdoor sports, such as hiking.

The patient’s treatment plan includes music, exercise, and meditation for stress reduction. He is encouraged to eat high-potassium foods and whole foods (meat, vegetables, and tubers) and to avoid sugars and alcohol. Supplements include coenzyme Q10 (150 mg daily), magnesium citrate malate (150 mg 3 times daily with meals and at bedtime), and taurine (1000 mg concurrent with the magnesium doses).

At a follow-up visit 2 weeks later, the patient reported a single short AF episode that resolved with the Valsalva maneuver. Follow-up visits at 3 and 6 months revealed that the patient had been free of any AF episodes.

Case 2

A 76-year-old woman had onset of AF 18 months previously. Her AF episodes can occur up to 3 times daily, and the duration is seconds to several minutes. The patient is hypertensive and maintains an approximately normal blood pressure with diltiazem and losartan potassium; her blood pressure at the initial visit was 135/84 mm Hg and increases up to 150/95 mm Hg at home. Flecainide acetate was prescribed to control the arrhythmia of the AF, and aspirin (325 mg daily) was recommended to decrease the possibility of thrombus.

The patient’s treatment plan included daily walking (weather permitting) and scaled weight lifting (according to patient tolerance) on a home gym. Diet changes include increasing protein (to ½ g per 1 lb of body weight) and eating high-potassium foods; she does not consume simple sugars. Supplements include arginine (sustained release, 1000 mg twice daily), magnesium citrate malate (150 mg 3 times daily with meals and at bedtime), taurine (1000 mg concurrent with the magnesium doses), and vitamin D3 (4000 IU daily).

At follow-up, the patient reported 2 short episodes of AF during the first week and no episodes during the second week. She had visited her cardiologist, who found that her serum magnesium level was too high (3.5 mg/dL [reference range, 1.7-2.2 mg/dL]). There were no signs of magnesium overdose. He suggested that she cut her magnesium dosage, and I recommended that we measure her red blood cell magnesium level first, which was 4.2 mg/dL (reference range, 3.5-7.1 mg/dL). Her blood pressure at the cardiologist visit was 122/78 mm Hg, so he discontinued diltiazem and continued with losartan potassium. We maintained the magnesium dosage. At the 1-month and 3-month follow-up visits, the patient reported no episodes of AF. She continued to be free of AF after 6 months.

Dan Carter, ND graduated from National College of Natural Medicine (NCNM) and completed a 2-year family practice residency. He was appointed to a full-time faculty position in 1997 and served as a core faculty member through 2003. He is a cofounder of IV Nutritional Therapy for Physicians, an organization that teaches intravenous therapy seminars, since 2001. He has been in private practice in Bozeman, Montana, since 2004. His practice focuses on the nutritional improvement of health, cardiovascular disease, weight loss, hormone restoration for men and women, and IV nutrient therapy. Dr Carter’s websites can be accessed at www.alpinephysicians.com and www.bznwtmgt.com.

Dan Carter, ND graduated from National College of Natural Medicine (NCNM) and completed a 2-year family practice residency. He was appointed to a full-time faculty position in 1997 and served as a core faculty member through 2003. He is a cofounder of IV Nutritional Therapy for Physicians, an organization that teaches intravenous therapy seminars, since 2001. He has been in private practice in Bozeman, Montana, since 2004. His practice focuses on the nutritional improvement of health, cardiovascular disease, weight loss, hormone restoration for men and women, and IV nutrient therapy. Dr Carter’s websites can be accessed at www.alpinephysicians.com and www.bznwtmgt.com.

References

1. Lloyd-Jones DM, Wang TJ, Leip EP, et al. Lifetime risk for development of atrial fibrillation: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2004;110(9):1042-1046.

2. Chutani SK, Imran N, Kanjwal Y. Atrial fibrillation: current concepts. Int J Health Sci. 2008;2(1):85-90.

3. Liu T, Shehata M, Li G, Wang X. Androgens and atrial fibrillation: friends or foes? Int J Cardiol. 2010;145(2):365-367.

4. Kaushik M, Sontineni SP, Hunter C. Cardiovascular disease and androgens: a review. Int J Cardiol. 2010;142(1):8-14.

5. Fitzmaurice DA. Goodbye to electrical cardioversion for atrial fibrillation? http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/584780. Accessed August 2, 2011.

6. Sample SA. Management of patients with atrial fibrillation based on ACC/AHA guidelines. Paper presented at: Primary Care Symposium, Billings Clinic; April 1, 2011; Billings, MT.

7. Fitzmaurice DA. The NICE guidelines on atrial fibrillation: a personal view. Br J Cardiol. 2007;14:29-30.

8. Drugs.com. Amiodarone side effects. http://www.drugs.com/sfx/amiodarone-side-effects.html. Accessed August 2, 2011.

9. Gitter MJ, Jaeger TM, Petterson TM, et al. Bleeding and thromboembolism during anticoagulant therapy: a population-based study in Rochester, Minnesota. Mayo Clin Proc. 1995;70(8):725-733.

10. FDA approves Xarelto (rivaroxaban tablets) to help prevent deep vein thrombosis in patients undergoing knee or hip replacement surgery [press release]. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc. July 1, 2011.

11. Family Practice Notebook. Carotid sinus massage. http://www.fpnotebook.com/cv/exam/CrtdSnsMsg.htm. Accessed August 3, 2011.

12. Jaminet P, Jaminet SC. Perfect Health Diet: Four Steps to Renewed Health, Youthful Vitality, and Long Life. YinYang Press; October 12, 2010.

13. Adamopoulos C, Pitt B, Sui X, Love TE, Zannad F, Ahmed A. Low serum magnesium and cardiovascular mortality in chronic heart failure: a propensity-matched study. Int J Cardiol. 2009;136(3):270-277.

14. Ho KM, Sheridan DJ, Paterson T. Use of intravenous magnesium to treat acute onset atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis. Heart. 2007;93(11):1433-1440.

15. Satoh H, Sperelakis N. Review of some actions of taurine on ion channels of cardiac muscle cells and others. Gen Pharmacol. 1998;30(4):451-463.

16. Chazov EI, Malchikova LS, Lipina NV, Asafov GB, Smirnov VN. Taurine and electrical activity of the heart. Circ Res. 1974;35(suppl 3):3-11.

17. Eby, G, Halcom WW. Elimination of cardiac arrhythmias using oral taurine with l-arginine with case histories: hypothesis for nitric oxide stabilization of the sinus node. Med Hypotheses. 2006;67(5):1200-1204.

18. Flanagan JL, Simmons PA, Vehige J, Willcox MD, Garrett Q. Role of carnitine in disease. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2010;7:e30. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2861661/?tool=pubmed. Accessed August 19, 2011.

19. Amat di San Filippo C, Taylor MR, Mestroni L, Botto LD, Longo N. Cardiomyopathy and carnitine deficiency. Mol Genet Metab. 2008;94(2):162-166.

20. Roth EM, Harris WS. Fish oil for primary and secondary prevention of coronary heart disease. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2010;12(1):66-72.