Herbal Protocols for Impetigo and Erysipelas

Jilian Stansbury, ND

Group A streptococci are a leading human pathogen and worldwide health issue. In chronic skin infections, the goal of supporting a healthy ecosystem to invite desirable microbes and protective skin barriers should be equal to the combat of the pathogen. Herbs are excellent in this regard as they can simultaneously support skin health and provide antimicrobial effects. Many plants are known to have activity against streptococcal infections, but because of the fairly serious sequelae of such infections that are poorly treated, antibiotics are sometimes used to ensure rapid effects and prevent complications. This article aims to review the common types of streptococcal infections of the skin, impetigo and erysipelas, and exemplify herbal management approaches.

The Seriousness of Streptococcal Skin Infections

As with strep throat and other group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal infections, autoimmune reactions are possible with such infections of the skin. The body will create antibodies against the streptococcal bacteria, which then fuse together into antigen-antibody complexes that in some cases may bind to the basement membrane of the glomeruli in the kidneys and lead to a specific type of glomerulonephritis or bind tissues of the testicles and result in sterility. For this reason, all manner of streptococcal infections must be treated aggressively and fully; the longer a streptococcal infection lingers, the greater is the likelihood that a large quantity of antigen-antibody complexes may be generated. Due to the possibility of such streptococcal infections causing autoimmune phenomena that may damage the kidneys, many practitioners choose to treat erysipelas with antibiotics to reduce the possibility of sequelae. Following are herbal and natural therapy options to use in tandem with antibiotics or as stand-alone therapies.

Impetigo

Impetigo is one of the most common of all skin infections. It is a superficial skin infection that can be due to Streptococcus pyogenes or Staphylococcus aureus and is considered highly contagious. Lesions are commonly on the face but may occur anywhere on the body, and they appear as thick dark yellowish crusts overlying wet, raw, inflamed skin. Infection usually follows a break in the skin such as an injury or an insect bite, or it may follow lice, scabies, or fungal infection where there has been a lot of scratching and trauma to the skin. Superficial vesicles and pustules are the first to emerge, with thick yellow crusts quickly following. Ecthyma is a more severe and painful variety, more common on the arms and legs than the face, and may leave permanent scars if not promptly and effectively treated. The bulk of medical literature reports that both systemic and topical antibiotic therapies for impetigo are effective, with many physicians using both to be on the safe side. Oral erythromycin will reduce the likelihood of poststreptococcal autoimmune issues and is a leading systemic therapy. I have treated impetigo effectively without pharmaceutical antibiotics by using topical herbal applications and oral immune and alterative support.

Erysipelas

Erysipelas is a type of infectious cellulitis due to group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal infection. It usually presents as a well-demarcated area that is red, swollen, and tender and associated with regional lymphadenopathy. Erysipelas most commonly affects one side of the face or a single limb and may be accompanied by systemic symptoms such as fever, chills, and malaise. Erysipelas is easy to diagnose due to the characteristic appearance, but occasionally vesicles and bullae may emerge within the lesion. When chronic, erysipelas may damage local lymphatic vessels, resulting in permanent lymphedema. A 2-week course of penicillin or erythromycin is the usual therapy, though Echinacea, Phytolacca, and other herbs as exemplified below may serve as an alternative to those for whom antibiotics are contraindicated. Herbal approaches are also useful as a supportive accompanying therapy. I have seen only 2 cases of erysipelas, one treated successfully with systemic herbal immune support and one treated with antibiotics because of the concomitant nephritis symptoms present at the initial appointment.

Herbal Alternatives to Treat Streptococcal Infections

Herbal alternative approaches may be just as effective as antibiotics in the treatment of streptococcal infections of the skin, but it is important that the physician must closely follow all cases and be prepared to promptly alter the course of treatment if a streptococcal infection does not respond readily within the first 24 hours of initiating therapy. Any pain at the costovertebral angle or unusually severe toxic presentation is an ominous sign that may warrant antibiotics or particularly vigilant alternative therapies. Some research has shown that poststreptococcal complications such as glomerulonephritis are more common in those with poor nutritional status1-3; thus, it might be wise to implement nutritional supplementation and dietary advice for anyone with a streptococcal infection.

I have had the opportunity to treat 6 cases of strep throat with herbal therapies and ran follow-up throat cultures after 7 to 10 days to prove the efficacy of the treatment; the therapy was effective in all cases, and follow-up throat cultures were negative for Streptococcus. The classic “HEMP” formula (Hydrastis, Echinacea, Myrrha, and Phytolacca) is indeed effective for streptococcal throat infections, as folklore contends. These same herbs might therefore be used topically on streptococcal infections of the skin. Hydrogen peroxide creams were reported to be as effective as topical antibiotics in clinical cases of impetigo4; thus, skin washes might include hydrogen peroxide as part of or prior to herbal applications. Blepharitis5 and infected umbilical cords in infants6 may also be due to streptococcal infections, and treatments might follow some of the same guidelines as for impetigo and erysipelas, listed below.

Published Research on Herbs and Streptococcal Infections

Plants with demonstrated activity against Streptococcus strains include Allium sativum,7 Coptis,8 Ligusticum,9 Satureja hortensis,10 Capsicum species,11 Cordyceps,12 Achillea,13 Sophora flavescens,14 and Ipomoea batatas.15 Quercus galls have been noted to have activity against Streptococcus mutans, Streptococcus salivarius, and Streptococcus sanguis16 and would make a good skin wash for impetigo due to additional astringent properties. Pelargonium sidoides is noted to deter adhesion of S pyogenes to human epithelial cells.17,18 Mycelia of the medicinal mushroom Cordyceps has shown an ability to protect mice from developing symptoms when exposed to group A streptococci.12

There are no published studies to date on tea tree oil (Melaleuca) for impetigo, but I believe that essential oils can be highly effective when used topically on impetigo or other streptococcal infections. One animal study19 showed that Melaleuca alternifolia had a strong inhibitory effect on group A S pyogenes infection, while simultaneously limiting inflammatory cytokine release. There are several positive trials using Melaleuca essential oil in the treatment of methicillin-resistant S aureus,4 another potential cause of impetigo.

Many common essential oils have been shown to have activity against drug-resistant strains of Staphylococcus and Streptococcus, including eucalyptus, tea tree, thyme, lavender, lemon, lemongrass, cinnamon, grapefruit, clove bud, sandalwood, peppermint, and sage oil.20 Of this list, I have the most experience using tea tree and lavender directly on the skin and find them versatile and effective against a variety of infections and well tolerated. I also use thyme oil but only highly diluted because if used neat, thyme oil is very irritating on the skin.

Streptococcus mutans is associated with dental caries. Albizia myriophylla, Alpinia galanga, Avicennia marina, and Ocimum sanctum have activity against S mutans.21 Lippia sidoides in the mouth was demonstrated in one clinical study22 to deter S mutans and dental caries.

Treatment Approach to Impetigo and Streptococcal Infections of the Skin

Patients with streptococcal infections of the skin might be treated with topical skin washes or applications, as well as an internal immune-modulating and antimicrobial formula, as exemplified below. Those plants with the greatest astringent and antimicrobial effects might be used topically, while general immune supportive and alterative herbs could be taken orally for systemic antimicrobial support. Alteratives might also be included in oral formulas or in convalescent formulas to help “clean” the ecosystem, creating a less hospitable environment for pathogenic bacteria, including Streptococcus.

Skin “Stains” for Streptococcal Infections

Gentian violet and iodine, while messy, are both excellent for skin infections and can be combined with herbs for topical application. Gentian violet is a traditional treatment for oral thrush and other common epithelial infections and may also be effective against pyodermas, the term for infectious skin conditions, including impetigo.23,24 As gentian violet is inexpensive and easy to apply, it might be on the list of possible Streptococcus treatments, even if it does stain the skin purple.

Iodine is another long-standing skin disinfectant and home remedy for wound care and is believed to have less toxicity and allergic reactivity than chlorhexidine and other topical chemical disinfectants. One clinical study25 investigated the use of iodine as a skin disinfectant prior to surgery in over 1000 patients and reported excellent efficacy in terms of follow-up skin cultures for pathogenic microbes. The topical application of Melaleuca essential oil with iodine has also been shown to be safe and effective against molluscum contagiosum,26 suggesting antiviral and antibacterial effects. Iodine preparations have also been shown to deter Streptococcus species, along with other bacteria in the eye following cataract surgery.27 Iodine in the mouth has been shown to deter S mutans in children with extensive dental caries.28 Chronic blepharitis can be due to well-established biofilms, including Streptococcus pneumoniae biofilms, and iodine rinses have been shown to reduce bacterial colony counts by 90% to 99%.29,30

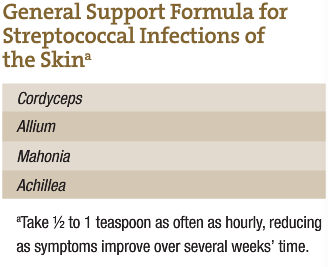

General Support Formula for Streptococcal Infections of the Skin

General Support Formula for Streptococcal Infections of the Skin

A general formula can be taken internally to offer both immune support and specific antimicrobial activity against Streptococcus. Both Mahonia and Achillea are also alterative agents, helping to alter the ecosystem and making it less hospitable to streptococcal bacteria. The dose should be aggressive if intended to replace antibiotics, and the formula should be amended if there is no improvement in 24 hours. If antibiotics are deemed necessary, complement their use with a formula such as this, and follow with a restorative formula and probiotic regimen. Combine an oral immune or alterative formula such as this with a topical application directly on the skin lesions.

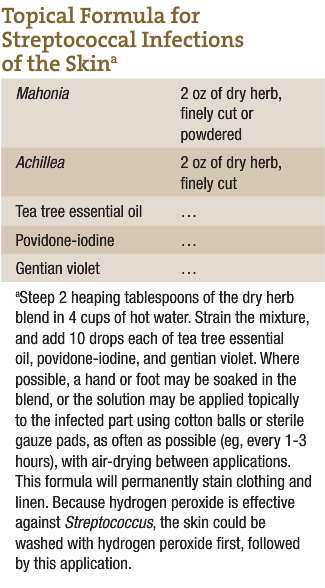

Topical Formula for Streptococcal Infections of the Skin

Both Mahonia and Achillea have been shown to have activity against Streptococcus, and both are readily available in tincture and dry form to craft topical skin washes. The dry form is less expensive and is best for topical preparations. The addition of essential oils, iodine, and gentian violet lends this formula multiple mechanisms of action, but care must be taken to reserve such formulas for topical use only. For all topical preparations for impetigo and ecthyma, it is important to allow full air-drying between applications.

Internal Formula for Erysipelas

Internal Formula for Erysipelas

This fairly all-purpose antimicrobial formula may be useful in cases of erysipelas. Phytolacca and Echinacea are emphasized in this formula due to an affinity for lymphatic channels that are affected in erysipelas. Atropa belladonna may be added in cases where the affected skin is red, swollen, hot, and throbbing.

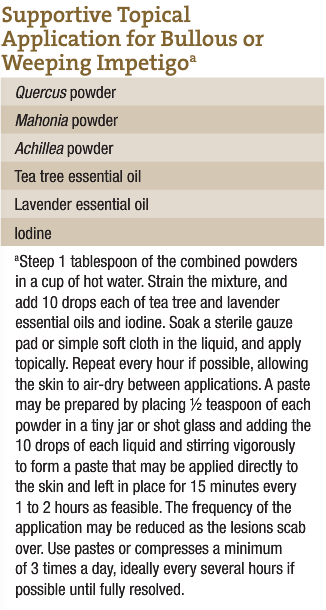

Supportive Topical Application for Bullous or Weeping Impetigoa

Because of the moist character of impetigo, astringents such as Quercus are indicated to help the crusts harden and scab over. Some cases of impetigo may be particularly bullous or vesicular, in which case astringent herbs are especially needed. The use of powders in this formula allows it to also be prepared as a paste for topical use and as a compress. Allow for full air-drying between applications.

Conclusion

While streptococcal infections can cause serious illnesses as well as have serious sequelae, we need not fear that alternative medicines are any less effective than antibiotics. Streptococcal infections usually respond very well to aggressive and vigilant herbal approaches. The oral and topical approaches described in this article are to serve as examples. Clinicians can use the basic ideas and alter the formulas as needed to suit individual patients.

Dr Jill Stansbury ND

Jillian Stansbury, ND has practiced in SW Washington for nearly 20 years, specializing in women’s health, mental health and chronic disease. She holds undergraduate degrees in medical illustration and medical assisting, and graduated with honors in both programs. Dr. Stansbury also chaired the botanical medicine program at NCNM and has taught the core botanical curricula for more than 20 years. In addition, Dr. Stansbury also writes and serves as a medical editor for numerous professional journals and lay publications, plus teaches natural products chemistry and herbal medicine around the country. At present she is working to set up a humanitarian service organization in Peru and studying South American ethnobotany. She is the mother of two adult children, and her hobbies include art, music, gardening, camping, international travel and studying quantum and metaphysics.

References

- Berkowitz FE. Bacteremia in hospitalized black South African children: a one-year study emphasizing nosocomial bacteremia and bacteremia in severely malnourished children. Am J Dis Child. 1984;138(6):551-556.

- Hailemeskel H, Tafari N. Bacterial meningitis in childhood in an African city: factors influencing aetiology and outcome. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1978;67(6):725-730.

- Isaack H, Mbise RL, Hirji KF. Nosocomial bacterial infections among children with severe protein energy malnutrition. East Afr Med J. 1992;69(8):433-436.

- Christensen OB, Anehus S. Hydrogen peroxide cream: an alternative to topical antibiotics in the treatment of impetigo contagiosa. Acta Derm Venereol. 1994;74(6):460-462.

- Ubani UA. Bacteriology of external ocular infections in Aba, South Eastern Nigeria. Clin Exp Optom. 2009;92(6):482-489.

- Janssen PA, Selwood BL, Dobson SR, et al. To dye or not to dye: a randomized, clinical trial of a triple dye/alcohol regime versus dry cord care. Pediatrics. 2003;111(1):15-20.

- Iwalokun BA, Ogunledun A, Ogbolu DO, et al. In vitro antimicrobial properties of aqueous garlic extract against multidrug-resistant bacteria and Candida species from Nigeria. J Med Food. 2004;7(3):327-333.

- Choi UK, Kim MH, Lee NH. Optimization of antibacterial activity by gold-thread (Coptidis rhizoma Franch) against Streptococcus mutans using evolutionary operation-factorial design technique. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2007;17(11):1880-1884.

- Xiao Y, Liu TJ, Huang ZW, et al. The effects of natural medicine on adherence of Streptococcus mutans to salivary acquired pellicle. Sichuan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2004;35(5):687-689.

- Güllüce M, Sökmen M, Daferera D, et al. In vitro antibacterial, antifungal, and antioxidant activities of the essential oil and methanol extracts of herbal parts and callus cultures of Satureja hortensis L. J Agric Food Chem. 2003;51(14):3958-3965.

- Cichewicz RH, Thorpe PA. The antimicrobial properties of chile peppers (Capsicum species) and their uses in Mayan medicine. J Ethnopharmacol. 1996;52(2):61-70.

- Kuo CF, Chen CC, Luo YH, et al. Cordyceps sinensis mycelium protects mice from group A streptococcal infection. J Med Microbiol. 2005;54(pt 8):795-802.

- Candan F, Unlu M, Tepe B, et al. Antioxidant and antimicrobial activity of the essential oil and methanol extracts of Achillea millefolium subsp. millefolium Afan. (Asteraceae). J Ethnopharmacol. 2003;87(2-3):215-220.

- Wu YR, Gong QF, Fang H, et al. Effect of Sophora flavescens on non-specific immune response of tilapia (GIFT Oreochromis niloticus) and disease resistance against Streptococcus agalactiae. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2013;34(1):220-227.

- Pochapski MT, Fosquiera EC, Esmerino LA, et al. Phytochemical screening, antioxidant, and antimicrobial activities of the crude leaves’ extract from Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam. Pharmacogn Mag. 2011;7(26):165-170.

- Vermani A, Navneet P. Screening of Quercus infectoria gall extracts as anti-bacterial agents against dental pathogens. Indian J Dent Res. 2009;20(3):337-339.

- Janecki A, Conrad A, Engels I, et al. Evaluation of an aqueous-ethanolic extract from Pelargonium sidoides (EPs 7630) for its activity against group A-streptococci adhesion to human HEp-2 epithelial cells. J Ethnopharmacol. 2011;133(1):147-152.

- Conrad A, Jung I, Tioua D, et al. Extract of Pelargonium sidoides (EPs 7630) inhibits the interactions of group A-streptococci and host epithelia in vitro. Phytomedicine. 2007;14(suppl 6):52-59.

- Tsao N, Kuo CF, Lei HY, et al. Inhibition of group A streptococcal infection by Melaleuca alternifolia (tea tree) oil concentrate in the murine model. J Appl Microbiol. 2010;108(3):936-944.

- Martin KW, Ernst E. Herbal medicines for treatment of bacterial infections: a review of controlled clinical trials.

- J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003;51(2):241-246.

- Warnke PH, Becker ST, Podschun R, et al. The battle against multi-resistant strains: renaissance of antimicrobial essential oils as a promising force to fight hospital-acquired infections. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2009;37(7):392-397.

- Joycharat N, Limsuwan S, Subhadhirasakul S, et al. Anti–Streptococcus mutans efficacy of Thai herbal formula used as a remedy for dental caries. Pharm Biol. 2012;50(8):941-947.

- Lobo PL, Fonteles CS, de Carvalho CB, et al. Dose-response evaluation of a novel essential oil against Mutans streptococci in vivo. Phytomedicine. 2011;18(7):551-556.

- Berrios RL, Arbiser JL. Effectiveness of gentian violet and similar products commonly used to treat pyodermas. Dermatol Clin. 2011;29(1):69-73.

- Stoff B, MacKelfresh J, Fried L, et al. A nonsteroidal alternative to impetiginized eczema in the emergency room. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63(3):537-539.

- Tschudin-Sutter S, Frei R, Egli-Gany D, et al. No risk of surgical site infections from residual bacteria after disinfection with povidone-iodine-alcohol in 1014 cases: a prospective observational study. Ann Surg. 2012;255(3):565-569.

- Markum E, Baillie J. Combination of essential oil of Melaleuca alternifolia and iodine in the treatment of molluscum contagiosum in children. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11(3):349-354.

- Hosseini H, Ashraf MJ, Saleh M, et al. Effect of povidone-iodine concentration and exposure time on bacteria isolated from endophthalmitis cases. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2012;38(1):92-96.

- Simratvir M, Singh N, Chopra S, Thomas AM. Efficacy of 10% povidone iodine in children affected with early childhood caries: an in vivo study. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2010;34(3):233-238.

- Chronister DR, Kowalski RP, Mah FS, Thompson PP. An independent in vitro comparison of povidone iodine and SteriLid. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2010;26(3):277-280.