David J. Schleich, PhD

Nobody said it was going to be easy. The stakes have always been high socially and economically, but never so high as today. The biomedicine industry knows we are better organized now than back when it all began. We’re in better shape politically and educationally to contribute to the healthcare needs of North Americans now than back in Benedict Lust’s day. In fact, naturopathic medical education is making important strides all the time, and our detractors know it. At this point, there are mistakes we made long ago which we don’t want to reinvent. Naturopathic medical education has given us a new chance to keep up on an unforgiving social and economic racetrack.

Let’s do the numbers to make sense of those high stakes. In that economic category alone, the medical industry (hospitals, physician and clinical services, dental services, eye care, prescription drugs, nursing home and home health care) in America is bigger than the GDPs of all but a half-dozen countries in the world. The US figures are staggering. In 2014, the tab was $3.09 trillion. By 2017, the price tag will hit $3.57 trillion and keep on going. That means over 18% of US GDP today. The global average is 8.2%. The social stakes, though, are probably even more daunting. (Plunkett Research, 2014)

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports that 117 million Americans (that’s one-half of all adults) are burdened with chronic conditions (cancer, diabetes, heart disease, pulmonary conditions, stroke, hypertension). Naturopathic medicine is all about prevention, and has been from the start. With an equal playing field, there would be more of us already and those chronicity levels would be lower. Biomedicine has only begun recently to ring the bell of prevention, with some of its doctors understanding the term to mean more tests sooner, and others quickly co-opting the terminology and tinkering with modalities into the bargain. For example, what on earth is an MD doing writing Wheat Belly and another MD writing Grain Brain? Not only are the allopaths dominating the best-seller lists with books about topics the AMA would have scorned only a decade ago, their grip on the levers and engines of health care persist unabated. Their AMA consistently resists and tampers with the role other providers can contribute (likely much earlier) into that terrain of chronicity and end-of-life care for dying people. (Plunkett Research, 2014)

Three Mistakes Masquerading as “Do nots”

In this kind of universe, there are 3 brand-new, old mistakes we just must not make all over again. In a workshop conducted at NCNM in mid-April of this year in Portland, Oregon, a group of 8 naturopathic doctors, representing a collective clinical experience pool of 117 years (and still counting) put forward the following “do nots” for younger students of naturopathic medicine to consider:

- Don’t stop working toward consensus on identity and brand. The group insisted that we simply have to communicate to our students and recent grads some least common denominator of scope; protocols and philosophy must be an anchor and platform for professional formation. Doctors in every state association – and nationally – need to establish signifiers and identifiers for the social branding and social closure of naturopathic medicine. Who are we, in comparison to green allopaths, mixers, holistic advanced training nurses, and holistic medical doctors?

- Don’t settle for less than continuous, coordinated attention on the part of your national, state and provincial associations on equal positioning within the healthcare and higher education policy landscapes.

- Don’t defer or delay codifying the unique knowledge of naturopathic medicine via sustained, incremental research agenda in the following areas: clinical practice, clinical theory, educational methodology, and entry to practice curricula. In each category the goal must be currency, effectiveness, and applicability.

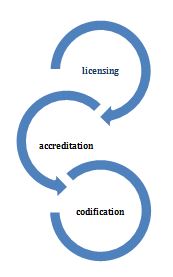

Skirmishes with biomedicine have accelerated since before Flexner because the massive rewards of dominance are not only monetary, but social. The initiatives of the General Education Fund in the quarter-century after that 1910 report, for example, gave biomedicine powerful purchase on the healthcare terrain, such that by mid-century, naturopathic medicine and other rivals were marginalized everywhere in North America. We got body-checked into that funk because we were not systematically organized around 3 areas of professional formation (Figure 1). What galvanized the effort and finally sustained it was the creation of viable naturopathic medical education institutions (people, buildings, equipment, libraries, faculty, teaching clinics, accreditors). The product of an increasingly successful educational enterprise in the naturopathic field was a growing cohort of naturopathic doctors determined not to repeat the mistakes of the past.

Finding Our Footing

Among other challenges which stalled the original momentum of the profession during the post-Flexner era were the complex rivalries among non-allopathic contenders themselves, ranging from Benedict Lust’s brand of naturopathy, through to sanipractitioners, irregulars, homeopaths, chiropractic mixers, mechanotherapists, hydropaths, physical culture practitioners, osteopaths, chiropractors, and drugless therapists, among others. (Whorton, 1982). This diversity of approaches and philosophies had not assembled into a coherent professional body that had found its footing, actively engaged in the key elements that let the clutch out for a profession: civil licensing of practitioners, civil accreditation of entry to practice education, and a sustained research agenda coupled with widespread publications that began the codification of naturopathic knowledge (Figure 1).

Reflective of the all-too-often uncoordinated approach to any or all of these critical ingredients is the actual nomenclature of legislation spanning “naturopathy acts” in the West, to “drugless therapist acts” in the East. For example, for almost a century the now-largest body of licensed naturopathic doctors in the world in Ontario was regulated under a law called the 1925 Drugless Therapy Act. However, in recent years these wobbles and inconsistencies have stabilized there and elsewhere. In the Ontario landscape, for example, a transition is occurring that is moving NDs, under something called the Regulated Health Professions Act, alongside other professions such as chiropodists, chiropractors, dental surgeons, optometrists, massage therapists, midwives, nurses, pharmacists, medical doctors, physiotherapists, and many more.

Key to this inclusion is education. After the closing of the original educational incubators for the profession, such as Lust’s schools in New York, and Lindlahr’s in Chicago, and Budden’s in Portland, the profession slowly but steadily committed to the long road of building standards and benchmarks in its educational investments. These now began to more coherently reflect Abraham Flexner’s insistence on a 4-year, residential post-baccalaureate program, coupled with “clerkships” or “internships,” and manifesting alongside traditional content (lately at risk) an experimental science knowledge platform at the outset. These now had continuous improvement built into their academic cycles. The old mistakes in this incubation ground became harder to make and harder to avoid.

David J. Schleich, PhD, is president and CEO of NCNM, former president of Truestar Health, and former CEO and president of CCNM, where he served from 1996 to 2003. Previous posts have included appointments as vice president academic of Niagara College, and administrative and teaching positions at St. Lawrence College, Swinburne University (Australia) and the University of Alberta. His academic credentials have been earned from the University of Western Ontario (BA), the University of Alberta (MA), Queen’s University (BEd), and the University of Toronto (PhD).

David J. Schleich, PhD, is president and CEO of NCNM, former president of Truestar Health, and former CEO and president of CCNM, where he served from 1996 to 2003. Previous posts have included appointments as vice president academic of Niagara College, and administrative and teaching positions at St. Lawrence College, Swinburne University (Australia) and the University of Alberta. His academic credentials have been earned from the University of Western Ontario (BA), the University of Alberta (MA), Queen’s University (BEd), and the University of Toronto (PhD).

References:

Berman, A. & Flannery, M. A. (2001). America’s Botanico-Medical Movements: Vox Populi. New York, NY: Pharmaceutical Products Press

Davis, W. (2014). Wheat Belly: Total Health. New York, NY: Rodale Press, Inc.

Perlmutter, D. (2013). Grain Brain. New York, NY: Little, Brown and Co.

Plunkett Research. Health Care Business Trends Analysis. Health Expenditures and Services in the U.S. November 11, 2014. Available at: www.plunkettresearch.com/trends-analysis/health-care-medical-business-market. Accessed May 22, 2015.

Whorton, J. C. (1982). Crusaders for Fitness: The History of American Health Reformers. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.