David Schleich, PhD

Like their counterparts in the public sector, CNME-accredited naturopathic colleges are constantly challenged by finances. Wherever they exist, naturopathic programs in both multi-program institutions and single-program entities (such as CCNM and SCNM) face many of the same cash flow and capital challenges as public-sector universities and smaller, nonprofit private-sector institutions. Each of these has financial processes and frameworks whose collective impact on the formation of the profession generally can be quite significant. For example, the program at Bridgeport University depends on an allocation model affected by the larger cash flow and finance priorities of a multi-program institution. The same is true in Lombard, Ill., for National University of Health Sciences (NUHS) and is increasingly true for Bastyr University. All these venues, in any case, derive the bulk of their cash flow from tuition and smaller revenue streams from annual campaigns and ancillary business activity. This is not the case in public-sector institutions, whose grant allocations constitute a good proportion of revenue; or in institutions with high endowment ratios, such as large research universities or small, private, liberal arts institutions like Reed College in Portland, for example.

Finance Challenges

Behind the scenes, the suppliers of higher education colleges, whether public or private and nonprofit, do tend to help us with all kinds of projects, big and small, but overall we have not been able to rely on public-sector financial support through state allocations, bond issues or capital grants. Our students, though, happily can access Title IV or Stafford loans in the U.S. or provincial and federal student loans and grants in Canada, thanks to our accreditation efforts; however, our endowment funds are collectively very small and bursary/scholarship money in very short supply.

In any case, the literature shows that the kinds of challenges and the extent of conversations about ways to address those challenges regarding finances in higher education resonate very clearly with naturopathic college leaders, too. As their counterparts in provincial and state institutions debate their capacity to meet high enrollment challenges or to realize their commitment to improve facilities and human resources, the parallels become increasingly transparent. On the public-sector side and on the private-sector side, especially in the nonprofit landscape, the financial picture is equally challenging.

There is a persistent anxiety in both arenas about protecting traditional university standards and academic freedom in the face of constantly declining operations grants and rapidly rising accountability expectations. Cumulatively, such pressures are discussed formally and informally by longtime faculty members who see the role of the university changing and who understand funding pressures as threats to the institutional autonomy of higher education (Bowen, 1980; Blackman and Segal, 1992; Gardner, 1988; Slaughter and Leslie, 1997; Graves, 1997; Peterson and Dill, 1997; Dionne and Kean, 1997; Breneman et al., 1997).

Professor Ian Steele brings a slightly different angle to these threats. In a University Affairs issue he comments, “Only an incurable optimist could minimize the relentless grind of budget cutbacks, retirements without replacements, and differential funding that have plagued us” (June 2003, p. 23). The leaders of the naturopathic colleges no doubt can recount these debates in their own board meetings and strategic planning sessions. The concern about attracting seasoned clinicians to classrooms is as much about the pool of available teachers as it is about remunerating them properly with scaled salary lines, sabbatical opportunities and professional development support.

In Canada, the early idea that naturopathic programs could find a safe zone within a public-sector university has not experienced much traction. In the U.S., there has been virtually no expectation of success in securing government funding for our programs, especially given the pressures on the funding of the universities and colleges at the state level.

Hough (1992), in this connection, writes persuasively about the financing of higher education, pointing out trends in the developed world, including the fact that “in most countries public expenditure on higher education failed to keep pace with trends in student numbers” (p. 1353). Taylor (1987) anticipated these observations by showing how rapid expansion had shifted to a more “broadly based institution” by the 1980s, given a change in the expectations of higher institutions by governments, but also by students. Hough explains that this phenomenon was “accentuated by the increased emphasis on universities becoming more competitive and market-oriented” (p. 1354). He goes on to clarify, though, that accompanying these changes were higher student fees, explained as “being a way of making [the universities] more entrepreneurial and customer-oriented” (p. 1356).

Hufner (1991) adds to the higher education literature about finances by injecting into the conversation a “claim for accountability” related to funding. He explains that the debates around the application of accountability “to processes of higher education occurred relatively recently” (p. 47). He points out that the dramatic increase in enrollment between the 1950s and 1970s led economists to “treat education as an industry” (p. 47) with an accompanying concern, as economic conditions contracted support for higher education in most developed countries, about the “economic appropriateness of academic qualifications” (p. 47) in economies that could not employ graduates. This, in turn, led to a growing conversation about how public money gets spent in such times of constraint on public higher education. These important ideas were not lost on the early leaders of the naturopathic schools who, in documents that date back as far as the late 1970s, often reference their institution’s state of educational finances and the need to “be accountable to the profession.”

Fund-Raising

Fund-Raising

In those same corners of the literature about the public financing of higher education, there is a parallel conversation focusing on the explosive growth in scholarship about advancement and fund-raising as key revenue-generators for the higher education sector (Fisher, 1989; Clark, 1998; Duderstadt, 2000). Duderstadt, for example, explains, “it has been suggested that some universities, from a financial perspective, look more like banks than educational institutions, since their most significant economic activity involves managing their endowment investments” (p. 171).

Darting around the literature as well is analysis of the enormous impact of information technology, not only on related instructional costs and management information systems, but also on the larger issue of funding those capital costs in higher education to sustain key instructional, operational and research strategies (Hanna, 2000). Pressure has mushroomed in the higher education sector for higher accountability in the face of such increased costs. Similar pressure exists in the naturopathic programs as learners ask for wireless access, electronic classrooms and online notes and articles. Calls for medical imaging to complement the important charting elements of clinical care are part of that growing need. The price tag for the technology is prohibitive and cannot come from recurrent tuition revenue streams.

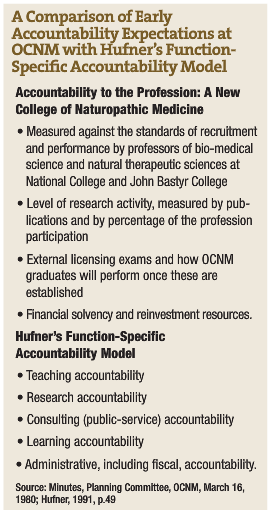

Articulating a taxonomy of accountability, Hufner’s “level-specific” and “function-specific” accountability model is surprisingly consistent with the “accountability to the profession” outlines that at least one naturopathic association was considering in the early 1980s as Ontario College of Naturopathic Medicine (OCNM), the earlier manifestation of CCNM, was taking shape. Hufner’s accountability framework (see the accompanying sidebar) suggests a recognition of the essential characteristics of higher education, descriptions and discussions of which abound in the literature. Once again, our higher education experience in the naturopathic colleges and programs parallels very closely that of the average state college or provincial university.

The similarities, then, between the financial realities and constraints of higher education institutions in the public sector and those in the nonprofit, private post-secondary sector are strong. Some would say they are more about magnitude than about the nature of the challenges.

Next month we shall explore the key characteristics of the higher education realm to see how we compare with the rest of that universe.

David Schleich, PhD is president and CEO of NCNM, former president of Truestar Health, and former CEO and president of CCNM, where he served from 1996 to 2003. Other previous posts have included appointments as vice president academic of Niagara College, and administrative and teaching positions at St. Lawrence College, Swinburne University (Australia) and the University of Alberta. His academic credentials have been earned from the University of Western Ontario (BA), the University of Alberta (MA), Queen’s University (BEd) and the University of Toronto (PhD).

David Schleich, PhD is president and CEO of NCNM, former president of Truestar Health, and former CEO and president of CCNM, where he served from 1996 to 2003. Other previous posts have included appointments as vice president academic of Niagara College, and administrative and teaching positions at St. Lawrence College, Swinburne University (Australia) and the University of Alberta. His academic credentials have been earned from the University of Western Ontario (BA), the University of Alberta (MA), Queen’s University (BEd) and the University of Toronto (PhD).

References

Blackman C and Segal N: Industry and higher education. In Burton Clark and Guy Neave (Eds), The Encyclopedia of Higher Education, Vol 2, Oxford, 1992, Pergamon Press, pp 841-851.

Bowen HR: The Costs of Higher Education, San Francisco, 1980, Jossey-Bass.

Breneman DW et al: Shaping the Future: Higher Education Finance in the 1990s, San Jose, 1997, California Higher Education Policy Center.

Clark Burton R: The entrepreneurial university: demand and response, Tertiary Education and Management, 4(1):5-16, 1998.

Dionne JL and Kean T: Breaking the Social Contract: The Fiscal Crisis in Higher Education. Report of the Commission on National Investment in Higher Education, New York, 1997, Council for Aid to Education.

Duderstadt JJ: A University for the 21st Century, Ann Arbor, 2000, The University of Michigan Press.

Fisher JL and Quehl GH: The President and Fund Raising, New York, 1989, American Council on Education, MacMillan, p 238.

Gardner DP: The U.S. business – higher education forum: reviewing the experiment, Industry and Higher Education 2(2):85-90, 1988.

Graves William H: Free trade in higher education: the meta university, Journal on Asynchronous Learning Networks 1(1), 1997.

Hanna, Donald and associates: Higher Education in an Era of Digital Competition: Choices and Challenges, Madison, 2000, Atwood Publishing.

Hufner Klaus: Accountability. In Philip G. Altbach (Ed) International Higher Education: An Encyclopedia, Vol I, New York, 1991, Garland Publishing, pp 47-58.

Peterson MW and Dill DD: Understanding the competitive environment of the postsecondary knowledge industry. In Marvin W Peterson, David D Dill, Lisa Mets and associates (eds), Planning and Management for a Changing Environment: A Handbook on Redesigning Post-Secondary Institutions, San Francisco, 1997, Jossey-Bass, pp 3-29.

Slaughter S and Leslie L: Academic science and technology in the global marketplace. In S Slaughter and L Leslie, Academic Capitalism: Politics, Policies, and the Entrepreneurial University, Baltimore, 1997, Johns Hopkins University, pp 23-63.

Taylor W: Universities Under Scrutiny, Paris, 1987, OECD.

Hough JR: Finance. In Burton Clark and Guy Neave (Eds), The Encyclopedia of Higher Education, Vol 2, Oxford, 1992, Pergamon Press, pp 1353-1358.