Bronner Handwerger, ND

NDs strive to find the root cause of illness in order to understand the truth when looking at any given situation. Traditional medicine has postulated that the presence of excess testosterone in a male’s body might increase the likelihood of prostate cancer. Some years back the urological community tried to find a correlation between the levels of testosterone or DHT (dihydro-testosterone) and prostate cancer. They found that there was no correlation.

Fear of Testosterone

Nonetheless, the medical community has avoided the therapeutic use of testosterone for fear of cancer. In doing so, they have discouraged and prevented many men from attaining the benefits available from androgen replacement therapy.

We all are aware of the myriad conditions that arise from androgen deficiency. These range from hyperlipidemia, hyperinsulinism, metabolic syndrome, hypertension and cardiovascular disease to an increase in all cause mortality.

A major reason for this attitude toward testosterone and androgen replacement therapy is because of the testosterone that was used in the 1940s and 1950s. A patent medicine company sold a synthetic hormone called methyltestosterone, pawning it off as the real thing. After a few years of taking this chemical form, which does not exist in the human body, many men developed liver cancer and heart disease. The experts proclaimed that “testosterone therapy” was dangerous, so testosterone research died and did not wake up until the late 1980s with the use of safer, bioidentical testosterone (Dach, online posting).

Another reason that testosterone has a bad reputation is from its abuse in sports. After all, it is an anabolic hormone. Following the example of college and professional athletes trying to increase their abilities, many high school athletes began using anabolic steroids. This is an example of tragic, self-induced hormone overdose. In response to this, the U.S. Congress made testosterone a controlled substance like cocaine and morphine (Dach, online posting).

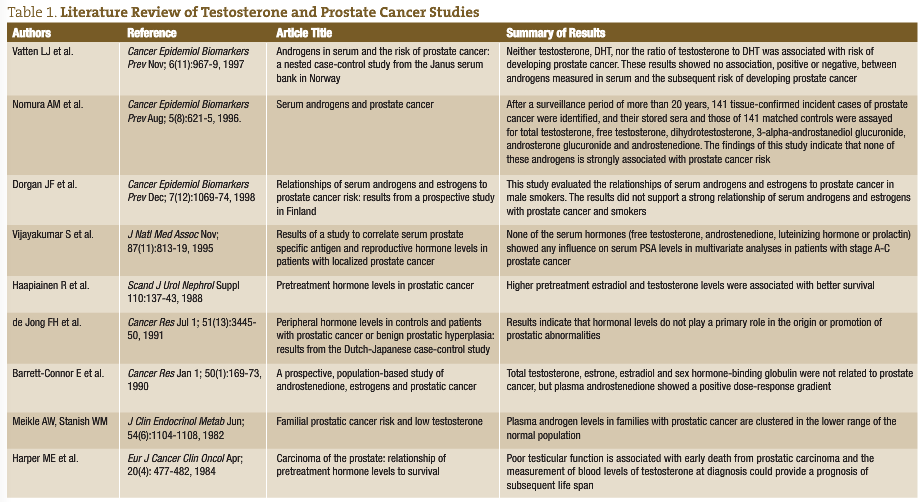

Another issue is that institutional medicine is opposed to the idea of testosterone treatment. In November 2002 the Institute of Medicine stated that existing scientific evidence does not justify claims that testosterone treatments can relieve or prevent certain age-related problems in men (Dach, online posting). As seen in Table 1, which summarizes a review of literature, no studies correlate levels of testosterone, DHEA or DHT to prostate cancer.

Last but not least is the notion that testosterone is not safe for the prostate. This notion is incorrect, as illustrated in the January 2004 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine, which reviewed numerous medical studies and found absolutely no evidence that testosterone therapy causes prostate cancer. In fact, the report notes that prostate cancer becomes more prevalent exactly at the time of the man’s life that testosterone levels decline.

In another study, researchers examined the effects on the prostate of testosterone replacement therapy in 40 men aged 44 to 78 and who had low testosterone levels.

The men received 150mg of either testosterone or a placebo via injection every two weeks for six months.

Biopsies performed on prostate tissue taken from the men before and after the study showed testosterone levels within the prostate increased only slightly among the men who received testosterone therapy, although their blood levels of the hormone increased to normal levels.

No treatment-related change in the number of cancer cases or cancer severity was found.

“The prostate risks to men undergoing TRT may not be as great as once believed, especially if the results of the pretreatment biopsy are negative,” wrote researcher Leonard Marks, MD of the UCLA School of Medicine, and colleagues in The Journal of The American Medical Association (2006).

Most of this debate stems from the study conducted in 1941 by Huggins and Hodges, which established the hormonal responsiveness of prostate cancer by reporting that marked reductions in testosterone by castration or estrogen treatment caused metastatic prostate cancer to regress, and also that administration of exogenous testosterone caused prostate cancer to grow. Many of us learned from our professors to describe the relationship of testosterone to prostate cancer as “fuel for a fire” and “food for a hungry tumor.” To this day, androgen ablation remains a mainstay of treatment for advanced prostate cancer.

On this note, a recent study illustrated that androgen deprivation therapy may not work. Published in the Journal of the American Medical Association (2008), the authors concluded that in men ages 66 and older, primary androgen deprivation therapy is not associated with improved survival among the majority of elderly men with localized prostate cancer when compared with conservative management (ie, deferral of treatment until necessitated by disease signs or symptoms in order to preserve quality of life).

This illustrates our need to change our thinking when it comes to androgens and prostate cancer.

Yet the true nature of this myth is revealed best by its historical origin – a blood test result in a single patient that was equivocal at best. Other investigators failed to note worrisome prostate cancer progression with testosterone administration and even reported beneficial subjective responses. Reviewing the relatively benign clinical course of their previously untreated patients, Fowler and Whitmore (1981) postulated that near-maximal stimulation of prostate cancer occurs at testosterone concentrations found in normal men. This saturation model is consistent with current data regarding testosterone and prostate cancer.

Discussion

The assertion that higher testosterone causes enhanced prostate cancer growth has persisted as a medical myth since 1941 despite all evidence to the contrary. Longitudinal studies have repeatedly and consistently rejected this hypothesis. And if testosterone is “food for a hungry tumor,” then why is the cancer rate only 1% for men receiving testosterone replacement therapy when one of seven hypogonadal men has biopsy-detectable prostate cancer?

In summary, there is not today – nor has there ever been, in my opinion – a scientific basis for the contention that a higher testosterone concentration causes prostate cancer growth, acutely or long-term. It is here where we find the danger of beliefs rather than science impairing our ability to behave logically and consistently. We must make our own informed decisions based on science and evidence presented to us rather than fear.

Bronner Handwerger, ND is the medical director of two integrative health centers in San Diego providing family medical and naturopathic care. He served as medical director for the D’Adamo Clinic and as an assistant clinical professor at UBCNM. He was a panel member for the White House Commission on Complementary and Alternative Medicine. He recently presented at the American Academy of Family Physicians conference and enjoys working with a wide range of patients specializing in the naturopathic approach to endocrinology, oncology and internal medicine.

Bronner Handwerger, ND is the medical director of two integrative health centers in San Diego providing family medical and naturopathic care. He served as medical director for the D’Adamo Clinic and as an assistant clinical professor at UBCNM. He was a panel member for the White House Commission on Complementary and Alternative Medicine. He recently presented at the American Academy of Family Physicians conference and enjoys working with a wide range of patients specializing in the naturopathic approach to endocrinology, oncology and internal medicine.

References

- Dach J: Low testosterone diagnosis and treatment, the male andropause. Available online: www.drdach.com/wst_page15.html

- Huggins C and Hodges CV: Studies on prostatic cancer, I: the effect of castration, of estrogen and of androgen injection on serum phosphatases in metastatic carcinoma of the prostate, Cancer Res 1:293-297, 1941.

- Lu-Yao GL et al: Survival following primary androgen deprivation therapy among men with localized prostate cancer, JAMA 300(2):173-181, 2008.

- Kolata G: Male hormone therapy popular but untested, NY Times 2002.

- Physician’s Desk Reference. Montvale, 2005, Thomson PDR, p. 3245.

- Rhoden EL and Morgentaler A: Risks of testosterone-replacement therapy and recommendations for monitoring, N Engl J Med 350(5):482-492, 2004.

- Bhasin S et al: Managing the risks of prostate disease during testosterone replacement therapy in older men: recommendations for a standardized monitoring plan J Androl 24:299-311, 2003.

- Barqawi AB and Crawford ED: Testosterone replacement therapy and the risk of prostate cancer: a perspective view, Int J Impot Res 17:462-463, 2005.

- Liverman CT and Blazer DG (eds): Institute of Medicine Report On: Testosterone and Aging. Washington, DC, 2004, National Academies Press.

- Sakr WA et al: High grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (HGPIN) and prostatic adenocarcinoma between the ages of 20-69: an autopsy study of 249 cases, In Vivo 8:439-443, 1994.

- Huggins C: Endocrine-induced regression of cancers, Cancer Res 27:1925-1930, 1967.

- Fowler JE and Whitmore WF: The response of metastatic adenocarcinoma of the prostate to exogenous testosterone, J Urol 126:372-375, 1981.

- Brendler H et al: Prostatic cancer: further investigations of hormonal relationships, Arch Surg 61:433-440, 1950.

- Prout GR and Brewer WR: Response of men with advanced prostatic carcinoma to exogenous administration of testosterone, Cancer 20:1871-1878, 1967.

- Pearson OH: Discussion of Dr. Huggins’ paper “control of cancers of man by endocrinological methods,” Cancer Res 17:473-479, 1957.

- Bubley GJ: Is the flare phenomenon clinically significant?, Urology 58:5-9, 2001.

- Kuhn JM et al: Prevention of the transient adverse effects of a gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogue (Buserelin) in metastatic prostatic carcinoma by administration of an antiandrogen (Nilutamide), N Engl J Med 321:413-418, 1989.

- Tomera K et al: The gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist Abarelix depot versus luteinizing hormone releasing hormone agonists leuprolide or goserelin: initial results of endocrinological and biochemical efficacies in patients with prostate cancer, J Urol 16:1585-1589, 2001.

- Freeland SJ and Partin AW: Prostate-specific antigen: update 2006, Urology 67:458-460, 2006.

- Hsing AW: Hormones and prostate cancer: what’s next?, Epidemiol Rev 23:42-58, 2001.

- Parsons JK et al: Serum testosterone and the risk of prostate cancer: potential implications for testosterone therapy, Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 14:2257-2260, 2005.

- Statin P et al: High levels of circulating testosterone are not associated with increased prostate cancer risk: a pooled prospective study, Int J Cancer 108:418-424, 2004.

- Chen C et al: Endogenous sex hormones and prostate cancer risk: a case-control study nested within the Carotene and Retinol Efficacy Trial, Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 12:1410-1416, 2003.

- Platz EA et al: Sex steroid hormones and the androgen receptor gene CAG repeat and subsequent risk of prostate cancer in the prostate-specific antigen era, Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 14:1262-1269, 2005.

- Barrett-Connor E et al: A prospective, population-based study of androstenedione, estrogens, and prostatic cancer, Cancer Res 50:169-173, 1990.

- Gann PH et al: Prospective study of sex hormone levels and risk of prostate cancer, J Natl Cancer Inst 88:1118-1126, 1996.

- Morgentaler A et al: Incidence of occult prostate cancer among men with low total or free serum testosterone, JAMA 276:1904-1906, 1996.

- Thompson IM et al: Prevalence of prostate cancer among men with a prostate-specific antigen level=4ng per milliliter, N Eng J Med 350:2239-2246, 2004.

- Lefkowitz GK et al: Followup interval prostate biopsy 3 years after diagnosis of high grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia is associated with high likelihood of prostate cancer, independent of change in prostate specific antigen levels, J Urol 168:1415-1418, 2002.

- Rhoden EL and Morgentaler A: Testosterone replacement therapy in hypogonadal men at high risk for prostate cancer: results of 1 year of treatment in men with prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia, J Urol 170:2348-2351, 2003.

- Bhasin S et al: Testosterone dose-response relationships in healthy young men, Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 281:E1172–E1181, 2001.

- Cooper CS et al: Effect of exogenous testosterone on prostate volume, serum and semen prostate specific antigen levels in healthy young men, J Urol 159:441-443, 1998.

- Behre HM et al: Prostate volume in testosterone-treated and untreated hypogonadal men in comparison to age-matched normal controls, Clin Endocrinol 40:341-349, 1994.

- Hoffman M et al: Is low serum free testosterone a marker for high grade prostate cancer?, J Urol 163:824-827, 2000.

- Massengill JC et al: Pretreatment total testosterone level predicts pathological stage in patients with localized prostate cancer treated with radical prostatectomy, J Urol 169:1670-1675, 2003.

- Ribeiro M et al: Low serum testosterone and a younger age predict for a poor outcome in metastatic prostate cancer, Am J Clin Oncol 20:605-608, 1997.

- Prehn RT: On the prevention and therapy of prostate cancer by androgen administration, Cancer Res 59:4161-4164, 1999.

- Algarte-Genin M et al: Prevention of prostate cancer by androgens: experimental paradox or clinical reality, Eur Urol 46:285-295, 2004.