Cori Lisa Burke, ND

Vis Medicatrix Naturae

Depression is one of the most common mental health disorders seen in clinical practice. In 2015, approximately 16.1 million adults in the US had experienced at least 1 major depressive episode within the past year.1 The lifetime prevalence of depression for adults in the US is estimated to be 16%.2 A variety of socioeconomic factors have been associated with an increased risk for depression, including middle-age, female gender, Native American ethnicity, lower income status, unemployment, being single or divorced, and having a disability.1

The DSM-IV defines major depressive disorder (MDD) as more than 2 episodes consisting of depressed mood along with a loss of interest in usually pleasurable activities (anhedonia) that occurs most days for the duration of at least 2 weeks. Other possible symptoms include fatigue, changes in sleeping or eating patterns, feelings of low self-esteem and self-worth, diminished concentration, and recurrent thoughts of self-harm and death.3

Conventional treatment of MDD typically consists of psychotherapy and pharmaceuticals.4 The effectiveness of various classes of antidepressants is similar, with response rates in clinical trials varying from 50% to 75%,5 and appears to be correlated with the initial severity of depressive symptoms: Clinically significant improvements are more likely in severe and chronic depression, and benefits are often negligible in mild-to-moderate depression.6 Despite their possible benefits, many patients are wary of antidepressants, citing concerns about adverse side effects, including fatigue, sleep disturbances, weight gain, gastrointestinal distress, and loss of libido.

Fortunately, naturopathic medicine offers many powerful modalities for patients with mood disorders including botanical therapies, nutraceuticals, homeopathy, flower essences, nutritional interventions, and stress management techniques. For patients with mild-to-moderate depression or those who prefer to avoid pharmaceutical approaches, well-chosen natural treatments may be an appropriate and effective option.

Case Study

Sue is a 45-year-old female who presented to my clinic in June 2016 for issues with fatigue and foggy thinking. At our first office visit, she rated her energy level as variable, ranging from 3 to 6 out of 10. She stated that, after a few hours of physical activity, she was often overcome by exhaustion. She also described frequent insomnia. Sue commonly delayed bedtime until she was completely exhausted, falling asleep around midnight and waking between 6:00 and 8:00 AM on most days.

Sue reported persistent and significant anxiety, which had plague her since childhood. During episodes of anxiety, she experienced symptoms of muscle tension in her shoulders, neck, and jaw. Although she had experienced multiple episodes of depression in her lifetime, at the time she came to see me, she said she was not experiencing depressive symptoms. She expressed concern about the effects that chronic stress may have on her overall health.

Sue’s diet was basically a standard American diet. She explained that her diet would suffer during bouts of depression. Her water intake was approximately 75 to 100 ounces of water daily and she did not consume alcohol or caffeinated beverages. Sue was not exercising regularly but she was physically active throughout the day, and discussed a desire to restart a home yoga practice. Significant findings on review of systems included intermittent tension headaches and migraines.

Her past medical history was significant for chronic post-traumatic stress disorder following repeated sexual abuse. She had also experienced multiple traumatic brain injuries (TBI). Sue reported a 16-month period starting in 2010 when she was frequently disassociating. She was often unable to eat or leave her house during this time and had trouble performing activities of daily living. She also reported intermittent episodes of vomiting and intense physical pain, which she related to somatic expressions of psychological pain. Sue had been unemployed for many years and was currently single and living alone.

Sue had been in counseling intermittently for well over a decade, and reported that she had tried multiple antidepressants without success. In fact, most of the medications worsened her depression and caused weight gain. The only medication she had found to be helpful was a drug containing amphetamine plus dextroamphetamine (known as Adderall), which had been prescribed for issues with cognition and concentration following the TBIs. At the time she came to see me, Sue was using Piper methysticum (kava kava) at a dose of 500-1000 mg PRN, up to BID, for anxiety. She was also supplementing with methylcobalamin and cholecalciferol.

I ordered a comprehensive array of lab tests and prescribed 350 mg of a magnesium at bedtime and advised her to continue taking her current dose of Piper methysticum as needed for anxiety.

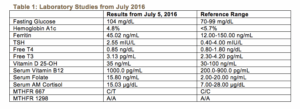

Sue’s laboratory testing revealed a heterozygous 677C/T MTHFR polymorphism, and a low-normal 25-OH vitamin D level despite daily supplementation. Her fasting glucose was mildly elevated at 104 mg/dL, however HbA1c was optimal at 4.8%. Her CBC, CMP, ferritin, lipids, cortisol, and thyroid studies were all otherwise within normal limits. Complete results of these laboratory studies are presented in Table 1. I prescribed a short-course of high-dose vitamin D3 along with a multivitamin containing 800 mcg of L–5–Methyltetrahydrofolate, 1000 mcg of vitamin B12, activated forms of other B vitamins, and trace minerals. The patient reported that magnesium was helping to improve her sleep quality and quantity and she was sleeping at least 8 hours each night.

At our 1-month follow-up, Sue said that she had been experiencing depressed moods. She described profound sadness, hopelessness, and a sense that her “future was bleak,” but said she was not having suicidal ideations. She was suffering from a lack of motivation and described needing 2 hours to get out of bed in the mornings. She stated that she was “numbing” her moods with television and overeating. She was also less careful to include protein and vegetables at meals.

Goals of Treatment

The goal of treatment in MDD is to help the patient return to full functioning and a high quality of life. Remission is defined as at least 3 weeks absent sad mood and anhedonia, with no more than 3 remaining symptoms of a major depressive episode.7 The prognosis for MDD is highly variable. Approximately 20% of individuals will experience a recurrence within the first 6 months following recovery from a major depressive episode. Furthermore, between 50% to 85% of people will have at least 1 recurrence, usually within 2–3 years of the initial depressive episode.1

For the many patients who experience chronic or recurrent depression, pragmatic goals should be focused on decreasing the severity and frequency of episodes. Improvements can be measured subjectively during the patient interview and by utilizing clinical tools such as the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) or Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D).

Herbal Prescriptions

A growing body of research indicates that herbal medicines can be a safe and effective in the treatment of MDD and other mood disorders. The best results may be had when herbal treatments are carefully individualized and adapted to changing needs as the clinical picture changes.

I prescribed an herbal formula to support the adrenal glands and nervous system containing Avena sativa, Melissa officinalis, Scutellaria lateriflora, Panax quinquefolius, and Rhodiola rosea. This formula was chosen in part to address her past history of PTSD and TBI. One week later, the patient reported that her energy had improved within a few days of starting the tincture and she was starting to wake feeling refreshed.

When another episode of MDD occurred, I added a second botanical formula, which contained Hypericum perforatum, Actaea racemosa, Verbena hastate, and a few drops of a Love-Lies-Bleeding flower essence. Flower essences can be a gentle yet powerful addition to an herbal tincture. They are highly individualized to specific types of mood concerns and may help to address the emotional and spiritual imbalances and traumas underlying a person’s experience. I find that many patients appreciate being involved in choosing flower essences to add to their treatment.

Two weeks later, the patient reported general improvements in depressed and anxious moods, especially when she was consistent with the tinctures. She noted that her headaches were also significantly less frequent when she was compliant with treatment. She reported increased feelings of calm and serenity and an ability to listen to her inner needs. She stated that her energy continued to be variable and appeared to directly correlate with her moods.

At subsequent visits the patient reported occasional worsening of mood, sleep, and energy that were triggered by significant life stressors and impending transitions in her life. She was still bothered by her general lack of energy; therefore, I prescribed a third herbal formula containing Lepidium meyenii, Withania somnifera, Glycyrrhiza glabra, Oplopanax horridus, and Olive flower essence. We continued to discuss stress management techniques and ways to reframe her experience of depression. I also encouraged her to begin treatment with a psychotherapist trained in Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR), which she reported to be very helpful.

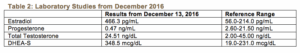

At our 6-month follow-up, Sue’s mood was greatly improved, but she was continuing to experience intermittent fatigue. Although she described regular cycles and normal menses, Sue requested hormone testing, which revealed elevated serum DHEA-S and estradiol levels, and a low-normal progesterone level on day 30 of her menstrual cycle. Complete results of these tests can be found in Table 2. I decided to remove Glycyrrhiza, which could contribute to the elevated DHEA-S,8 as well as Lepidium and Actaea, which may have estrogenic actions,9,10 from her protocol, and prescribed 2 new formulas: the first contained Hypericum perforatum, Verbena hastate, and Scutellaria lateriflora; the second contained Rhodiola rosea, Ocimum sanctum, Withania somnifera, and Vitex agnus-castus. The patient was then lost to follow-up as she had moved out of state, but she was strongly encouraged to follow through with repeat hormone testing and to re-establish care with a psychotherapist.

A Closer Look at Nervine Herbs

Nervine herbs should be considered as a foundational aspect of mood disorder treatment. They nourish and calm the nervous system and are especially important when stress, irritability, trauma, or anxiety is present. These herbs can be very helpful in restoring emotional balance.

Hypericum perforatum (St. John’s wort) is an herb traditionally indicated for neuralgic pain and viral infections, however it has also become 1 of the most widely used natural treatments for depression. In herbal folklore, Hypericum perforatum is said to “let the sun shine in” due to its doctrine of signatures wherein the leaves of the plant have small perforations. Numerous studies have shown Hypericum to be effective for treating mild-to-moderate MDD. In fact, Hypericum extracts may have better response and remission rates than antidepressants such as paroxetine in the treatment of moderate MDD.11 Hypericum has also been shown to have a favorable side-effect profile and tolerability when compared to antidepressant medications.12 Early research has suggested that Hypericum inhibits monoamine oxidase A (MAO-A);13 other studies, however, have refuted this finding.14 The antidepressant action of Hypericum may be due to its ability to increase serotonin production by inhibiting tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase (TDO) activity.15 The greatest clinical concern when prescribing Hypericum is potential herb-drug interactions, since Hypericum has been found to be a potent inducer of cytochrome P450 enzymes (most notably CYP3A4) and of P-glycoprotein.11

Avena sativa (oat, milky tops) is a trophorestorative chosen to address the history of prolonged stress and TBI. Avena is indicated for nervous exhaustion, melancholy, and diminished mental concentration.16 Avena has been found to affect neural activity in the region of the brain involved in cognition in healthy individuals, and may have a positive effect on cognition.17

There are unfortunately few scientific studies on Verbena hastate (blue vervain), but it has a long-standing use in traditional herbal medicine as a nervine and antispasmodic. Verbena is indicated for exhaustion and nervous depression and is specific for people who suppress their emotions and frustrations.16 Scutellaria lateriflora (American skullcap) is indicated for stress and anxiety, especially when there is a strong sense of overwhelm and oversensitivity.18,19 Scutellaria is also used to treat restless sleep and dull frontal headaches.16 Melissa officinalis (lemon balm) is often referred to as the “gladdening herb.” It is useful for nervous depression, especially when there is debility or weakness following chronic stress.20

A Closer Look at Adaptogenic Herbs

For those who experience MDD, it is common for life stressors to be a trigger for depressive episodes.Lack of motivation and low energy are also a significant concern for many people suffering from MDD.Because adaptogens have potent effects on the neuroendocrine system, and many are also immune modulators, these herbs are a good choice for many patients with MDD.

Withania somnifera (ashwagandha) is an Ayurvedic herb traditionally considered anti-inflammatory, anti-rheumatic, and adaptogenic. Withania is amphoteric in its action, as it can both stimulate and relax the nervous system; it is indicated for insomnia, fatigue, and debility caused by chronic stress.21 Over 35 chemical constituents of Withania have been studied, including alkaloids, steroidal lactones, saponins, and withanolides.22 Clinical trials suggest that it decreases serum cortisol levels and improves self-reported quality of life in people experiencing chronic stress and anxiety.23

Lepidium meyenii (Maca) is a medicinal food native to the Peruvian Andes. Although primarily studied for its effects on menopausal climacteric symptoms and infertility, animal studies suggest that Lepidum also has antidepressant and anxiolytic effects. Lepidium may act to regulate the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, increasing dopamine and norepinephrine levels in the brain while also decreasing serum cortisol. It has also been shown to reduce oxidative stress in the brain. Increased levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) have been found in the plasma and brains of individuals with MDD, thus suggesting that oxidative stress may be a contributor to depression.24

Glycyrrhiza glabra (licorice) has extensive and varied uses in many systems of medicine. Glycyrrhiza is anti-inflammatory, phytoestrogenic, and memory-enhancing, and it may help to relieve fatigue.25,26 Studies have shown that Glycyrrhiza has mineralcorticoid properties and increases circulating levels of unconjugated deoxycorticosterone, dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), and testosterone. This appears to be due to its glycyrrhetinic acid, a constituent that inhibits 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2, an enzyme that is involved in the inactivation of glucocorticoids.8

Oplopanax horridus (devil’s club) is an herb native to the Pacific Northwest. Oplopanax is a member of the Araliaceae family, of which the more familiar Panax quinquefolius (American ginseng) is also a member. Although dammarane saponins (active compounds found in Panax quinquefolius) are not found in any Oplopanax, it does contain various other triterpene glycosides.27 Oplopanax is traditionally considered a protective plant ally and is indicated for shy, timid individuals who have difficulty adapting to stressful situations.16

Discussion

The United States Preventative Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends that all adults and adolescents be screened annually for depression during primary care visits. A common screening tool is the 2-question PHQ-2. If positive, this should then trigger further evaluation using the PHQ-9, HAM-D, or another depression symptom inventory. Depression screening should be accompanied by appropriate treatments, referrals, and follow-up.28

Treatment of depressive disorders frequently requires an individualized, holistic, and integrative approach. Naturopathic medicine is especially well suited for the treatment of depression because of the many modalities available to practitioners. A comprehensive naturopathic treatment plan for depression may include the use of nervine and adaptogenic herbs, flower essences, nutraceutical supplements, lifestyle and diet modifications, and an appropriate referral for psychotherapy.

[References]

- Bose J, Hedden SL, Lipari RN, Park-Lee E. Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-FFR1-2015/NSDUH-FFR1-2015/NSDUH-FFR1-2015.pdf. Published September, 2016. Accessed January, 2017.

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). JAMA. 2003;289(23):3095–3105.

- Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. Managing Depressive Symptoms in Substance Abuse Clients During Early Recovery. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK64057/. Published 2008. Accessed January 19, 2017.

- American Psychiatric Association. Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Major Depressive Disorder, 3rd ed. National Guideline Clearinghouse. https://www.guideline.gov/summaries/summary/24158/Practice-guideline-for-the-treatment-of-patients-with-major-depressive-disorder-third-edition. Published October 2010. Accessed January, 2017.

- Linde K, Kriston L, Rucker G, et al. Efficacy and acceptability of pharmacological treatments for depressive disorders in primary care: Systematic review and network meta-analysis. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13(1):69–79.

- Fournier JC, DeRubeis RJ, Hollon SD, et al. Antidepressant drug effects and depression severity: A patient-level meta-analysis. JAMA. 2010;303(1):47–53.

- Rush AJ, Kraemer HC, Sackeim HA, et al. Report by the ACNP Task Force on response and remission in major depressive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2006;31:1841–1853.

- Al-Dujaili E, Kenyon C, Nicol M, Mason J. Liquorice and glycyrrhetinic acid increase DHEA and deoxycorticosterone levels in vivo and in vitro by inhibiting adrenal SULT2A1 activity. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2011;336(1-2):102–109.

- Meissner HO, Mscisz A, Reich-Bilinska H. Hormone-balancing effect of pre-gelatinized organic maca. Int J Biomed Sci. 2006;2(4):375–394.

- Powers CN, and Setzer, W. A molecular docking study of phytochemical estrogen mimics from dietary herbal supplements. In Silico Pharmacol. 2015;3(4).

- Seifritz E, Hatzinger M, Holsboer-Trachsler E. Efficacy of Hypericum extract WS(®) 5570 compared with paroxetine in patients with a moderate major depressive episode – a subgroup analysis. Int J Psychiatr Clin Prac. 2016;20(3):126–132.

- Apaydin EA, Maher AR, Shanman R, et al. A systematic review of St. John’s wort for major depressive disorder. Syst Rev. 2016 2;5(1):148.

- Suzuki O, Katsumata Y, Oya M, et al. Inhibition of monamine oxidase by hypericin. Planta Med. 1984; 50(3):272–274.

- Julia Sacher, MD, PhD, Sylvain Houle, MD, PhD, Jun Parkes, MSc, et al. Monoamine oxidase A inhibitor occupancy during treatment of major depressive episodes with moclobemide or St. John’s wort: an [11C]-harmine PET study. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2011; 36(6):375–382.

- Bano S, Ara I, Saboohi K, et al. St. John’s Wort increases brain serotonin synthesis by inhibiting hepatic tryptophan 2, 3 dioxygenase activity and its gene expression in stressed rats. Pak J Pharm Sci. 2014;27(5 Spec no):1427–1435.

- Tilgner S. Herbal medicine: from the heart of the earth. Creswell, OR: Wise Acres; 1999.

- Dimpfel W, Storni C, Verbruggen M. Ingested oat herb extract (Avena sativa) changes EEG spectral frequencies in healthy subjects. J Alternt Complement Med. 2011;17(5):427–434.

- Brock C1, Whitehouse J, Tewfik I, Towell T. American Skullcap (Scutellaria lateriflora): a randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled crossover study of its effects on mood in healthy volunteers. Phytother Res. 2014;28(5):692–698.

- Wood M. The earthwise herbal: a complete guide to New World medicinal plants. Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic Books; 2009: 323–325.

- Wood M. The earthwise herbal: a complete guide to Old World medicinal plants. Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic Books; 2009: 342–344.

- Thorne Research, Inc. Monograph: Withania somnifera. Altern Med Rev. 2004 Jun;9(2):211–214.

- Mishra LC, Singh BB, Dagenais S. Scientific Basis for the therapeutic use of Withania somnifera (Ashwagandha): A Review. Altern Med Rev. 2000;5(4):334–346.

- Chandrasekhar K, Kapoor J, Anishetty S. A prospective, randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled study of safety and efficacy of a high-concentration full-spectrum extract of ashwagandha root in reducing stress and anxiety in adults. Indian J Psychol Med. 2012;34(3):255–262.

- Ai Z, Cheng AF, Yu YT, et al. Antidepressant-like behavioral, anatomical, and biochemical effects of petroleum ether extract from maca (Lepidium meyenii) in mice exposed to chronic unpredictable mild stress. J Med Food. 2014;17(5):535–542.

- Shang H, Cao S, Wang J, et al. Glabridin from Chinese herb licorice inhibits fatigue in mice. Afr J Tradit Complement Altern Med. 2010;7(1):17–23.

- Simmler C, Pauli GF, Chen SN. Phytochemistry and Biological Properties of Glabridin. 2013; 90:160–184.

- Calway T, Du GJ, Wang CZ, et al. Chemical and pharmacological studies of Oplopanax horridus, a North American botanical. J Nat Med. 2012;66(2):249–256.

- Siu AL; US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Baumann LC, et al. Screening for depression in adults: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2016;315(4):380–387.

Cori Burke, ND, earned her doctorate in naturopathic medicine from the National University of Natural Medicine in 2014. Dr. Burke currently practices integrative family medicine at the Hillsboro Naturopathic Clinic in Hillsboro, OR. Her medical practice focuses on pediatrics, women’s health, and endocrine and digestive disorders. She has had a passion for natural medicine from the time she was a small child picking chocolate mint and pineapple weed in her parents’ yard and she still loves making her own medicines from cultivated & wild-crafted herbs.

Cori Burke, ND, earned her doctorate in naturopathic medicine from the National University of Natural Medicine in 2014. Dr. Burke currently practices integrative family medicine at the Hillsboro Naturopathic Clinic in Hillsboro, OR. Her medical practice focuses on pediatrics, women’s health, and endocrine and digestive disorders. She has had a passion for natural medicine from the time she was a small child picking chocolate mint and pineapple weed in her parents’ yard and she still loves making her own medicines from cultivated & wild-crafted herbs.