Dementia home created to showcase how people with the condition can live independently for longer

A show home designed around concepts and technologies which will allow people with dementia to live independently for longer has been officially opened.

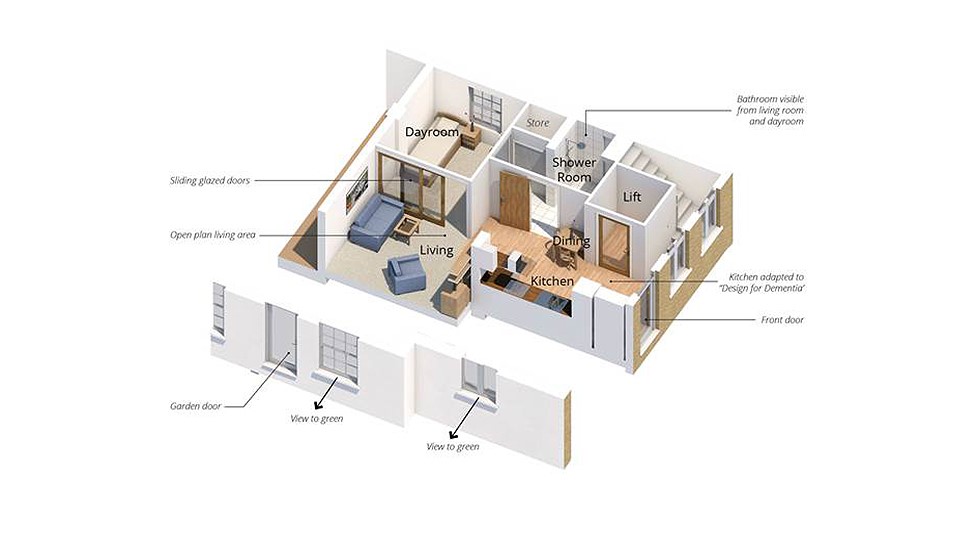

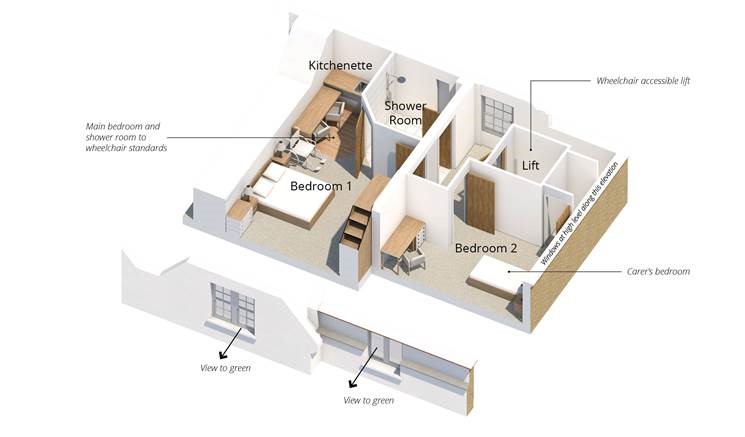

The house, at the BRE Innovation Park, in Watford, features a vast collection of intuitive ideas, all based on proven academic research, from simple open-plan living spaces to more hi-tech innovations such ‘talking cushions’, which promote activity after long periods of rest, sensory ‘smart chairs’, self-regulating climate control and safety sensors in high risk areas, such as the kitchen.

All of the features in the home were designed around a range of unique personas, created especially for the project, which reflect four progressive stages of dementia, from early on-set to end-of-life.

The converted 100sqm Victorian semi has been unveiled to 150 invited guests, all with an interest in dementia or health care, and television, radio and print journalists.

Lord Richard Best, Chair of the All Party Parliamentary Group on Housing and Care for Older People, was the guest of honour and gave a short talk before the ribbon was cut, on Wednesday, July 4.

The innovations and ideas have been devised by experts at Loughborough University, BRE and HLP Architects.

The house is open to the public, care-providers, local authorities, architects and anyone with an interest in dementia care to allow them to gather ideas, solutions and inspiration from the technology and design on show.

Examples of features include:

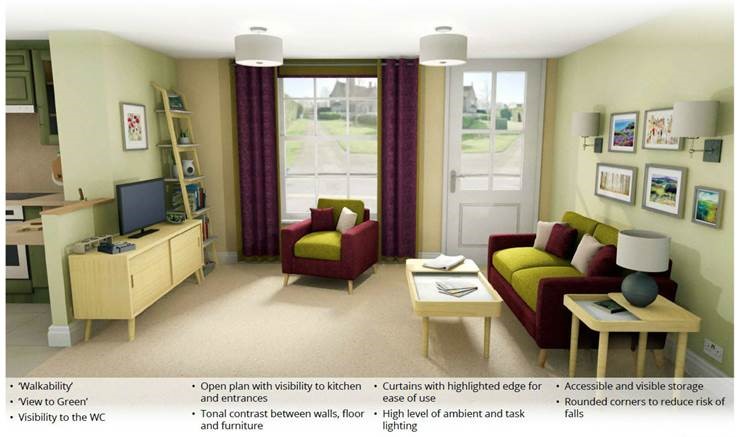

- Clear lines of sight and use of colour through the home help guide people towards specific rooms and reduce the risk for slips and trips

- Increased natural lighting, which has been shown to help people stay alert during the day and to sleep better at night

- Noise reduction features, to reduce stress and agitation

- A ‘talking cushion’ with inbuilt sensors to remind people to get up, walk around and get a drink because walking is beneficial for health and dehydration can cause cognitive problems

- Homely, simple and familiar interior design to help promote rest and relaxation

- Space to install a lift so the lounge does not become a bedroom when the stairs become difficult

One of the home’s more hi-tech features is an Acti-chair, which includes resistance bands with inbuilt sensors to guide strength, speed and direction of movement.

The chair was co-designed by Delft University of Technology and Loughborough’s Living Laboratory in partnership with people with dementia – using a simple system with emoji for feedback.

The Acti-chair not only promotes physical well-being but also improves memory by encouraging repetition of exercise patterns.

“Strength exercises can improve memory, even with three 30 minute sessions a week,” said Professor Eef Hogervorst, an expert in early dementia diagnoses and lifetime risk and protection.

“Many older people are sedentary and people with dementia often spend most of their time at home, which can enhance memory problems.

“Loughborough’s research by Jordan Elliott King and others shows that exercise promotes memory function and independence, also in people with dementia – so any features which encourage the uptake of activities, including the ‘talking cushions’, are key in the design of the house.”

Professor Hogervorst said that technology like the personas, ‘talking cushion’ and Acti-chair combined with the latest understanding of the condition is what makes the house an important step forward in dementia care.

“There are lots of small, simple changes people can make to their homes which will help with better independent living.

“The beauty of this project is that we’ve been able to create and adapt new technologies to support the knowledge we already have.”

Other technological advances include intelligent climate control and ventilation.

Professor Malcolm Cook and Dr Dashamir Marini, of Loughborough School of Civil and Building Engineering, have created a system which maintains the home at the optimum temperature and ensures enough fresh air gets into the house at all times of the day.

Dr Marini said: “Our goal was identical to any good house design – to develop a building that provides natural ventilation, space heating and domestic hot water.

“Ideal room temperature, air flow and climate should be the same for people with and without dementia – providing good thermal comfort and minimise energy consumption is a universal expectation.

“The only difference is, that with this design, we have incorporated an intelligent thermostat which monitors and adjusts itself in case of user-related errors, such as repeatedly turning up the temperature.”

Like all of the academics involved in the house, Dr Marini and Prof Cook will continue to collect data from the building, when it is occupied, to allow them to constantly refine their research and improve the home’s features.

The house will continue to provide invaluable data about interactions with technology and day-to-day living patterns and routines of any inhabitants.

“The house will be an invaluable tool for understanding numerous aspects of how people with dementia cope in an independent setting,” said Professor Hogervorst. “Everything we learn will go into improving the lives of people with the condition as well as back into the BRE home to make it an ever-evolving and progressing project.”

The demonstration house cost £300,000 to create, but the figure is not reflective of the amount people will have to spend to incorporate many of the ideas in their own homes.

As well as the hi-tech facets, the home is packed with simple, inexpensive solutions to the problems faced by people with dementia.

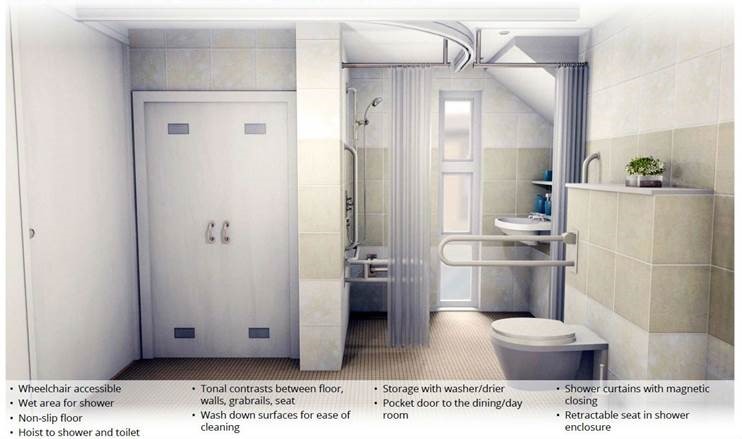

General adapted living features include non-scalding faucets, self-closing fridge doors, glass cabinets, simple switches, large clocks and furniture with no protruding corners to minimise injuries from falls.

Other design ideas focus on reducing accidents and confusion and promoting independence, by using good light, have adequate contrast between floors and walls and no loose rugs or fittings.

The house has been designed to show adaptations for different stages of the disease

Professor Sue Hignett, Charlotte Jais and Prof Hogervorst devised a number of personas, each with specific care needs, which have been used to guide the design and features of the house.

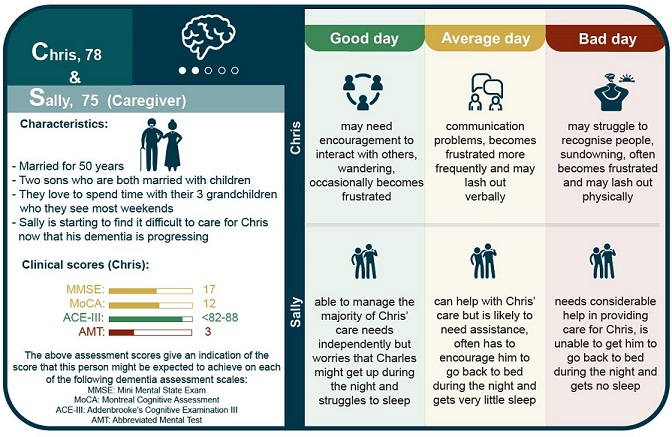

The main narrative of the project is based on the care needs of Chris and Sally – a couple living with the progressive stages of dementia.

Professor Hignett said: “Providing care and treatment at home presents challenges for people living with dementia whether care is delivered from one or multiple organisations or within different models of home care, for example, the hospital in the home, patient-centred medical home, home first policies and ageing-in-place.

“We know that a well-designed care environment can improve quality of life and enable independence.

“For this research, we considered a range of activities, including personal hygiene, mobilisation, and nutrition, as well as later stage nursing care for medication administration, tube feeding, and more home care technology – for example a ventilator or electric wheelchair.

“We used scientific information to create descriptions and videos to bring the voices of the people living with different stages of dementia to help communicate their abilities, limitations and preferences.”

The personas focussed on the symptoms, care requirements and design needs of four fictitious sufferers at different stages of dementia – Alison, Barry, Christine and David.

Each persona demonstrates good and bad days and allows families to identify at what stage of the disease they’re loved ones are closest to, and subsequently seek the correct care.

Professor Hignett said: “This research was needed because we know that dementia design guidelines have been criticized for mostly relying on professional consensus and stakeholder opinions than robust research evidence.

“Our design is firmly based on robust scientific evidence.”

Dementia care costs families around £18 billion a year and affects about 850,000 people in the UK. The figure is expected to rise to more than one million in the UK by 2025.

Two-thirds of the cost of dementia is paid by those who suffer from the condition and their families

This is in contrast to other conditions, such as heart disease and cancer, where the NHS provides care that is free at the point of use.

Calculating the savings made by adapting people’s homes would depend on a case-by-case basis.

BRE spokesperson Dr David Kelly said the average cost of dementia care in the UK is between £30,000 to £40,000 per annum.

He said: “Many of the ideas put forward in the prototype home are just good sense for us all to incorporate into our properties to adapt to the process of ageing.

“Creating environments which allow people to live independently at home for longer could save a significant amount.

“That money could instead be channelled into research that alleviates the condition and reduces the emotional stress to the individual.”

Press release reprinted with permission from Loughborough University

Image Copyright: <a href=’https://www.123rf.com/profile_stockbroker’>stockbroker / 123RF Stock Photo</a>

Node Smith, ND, is a naturopathic physician in Portland, OR and associate editor for NDNR. He has been instrumental in maintaining a firm connection to the philosophy and heritage of naturopathic medicine among the next generation of docs. He helped found the first multi-generational experiential retreat, which brings elders, alumni, and students together for a weekend camp-out where naturopathic medicine and medical philosophy are experienced in nature. Four years ago he helped found the non-profit, Association for Naturopathic ReVitalization (ANR), for which he serves as the board chairman. ANR has a mission to inspire health practitioners to embody the naturopathic principles through experiential education. Node also has a firm belief that the next era of naturopathic medicine will see a resurgence of in-patient facilities which use fasting, earthing, hydrotherapy and homeopathy to bring people back from chronic diseases of modern living; he is involved in numerous conversations and projects to bring about this vision.

Node Smith, ND, is a naturopathic physician in Portland, OR and associate editor for NDNR. He has been instrumental in maintaining a firm connection to the philosophy and heritage of naturopathic medicine among the next generation of docs. He helped found the first multi-generational experiential retreat, which brings elders, alumni, and students together for a weekend camp-out where naturopathic medicine and medical philosophy are experienced in nature. Four years ago he helped found the non-profit, Association for Naturopathic ReVitalization (ANR), for which he serves as the board chairman. ANR has a mission to inspire health practitioners to embody the naturopathic principles through experiential education. Node also has a firm belief that the next era of naturopathic medicine will see a resurgence of in-patient facilities which use fasting, earthing, hydrotherapy and homeopathy to bring people back from chronic diseases of modern living; he is involved in numerous conversations and projects to bring about this vision.