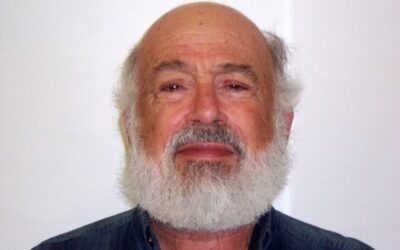

Robin DiPasquale, ND, RH(AHG)

In our current time, many health concerns being presented to doctors are seemingly linked to the function of the immune system. Some people are challenged with recurrent acute illnesses like colds and flu, where their immune system is not able to protect them upon repeated exposure to bacteria and viruses. Others are challenged with seasonal or ongoing allergies, a sign their immune system is working in overdrive and overreacting. And in the more chronic health challenges including arthritis, psoriasis, eczema, asthma, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, interstitial cystitis, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, ankylosing spondylitis, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), multiple sclerosis (MS), and an array of other chronic conditions, it seems the immune system has gone aberrant and turned its defenses on itself. This is the elusive and ever expanding category of autoimmune diseases.

Etiology

There are numerous ideas regarding the etiology of autoimmune diseases. Most NDs understand the connection to the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Damaged, inflamed mucous membranes result in leaky gut, which can then lead to antibody-antigen immune reactions and secondary systemic immunological disorders. Immunological cross-reactivity develops when the immune system is provoked, then confused by the similarity between bacterial, viral, or other antigens and those of its own tissues, and attacks both. In this theory, bacteria, viruses, and fungi may be causative agents that trigger the immune system overreaction. In some autoimmune conditions, molecular mimicry is considered the triggering factor, with 2 examples being HLA-B27 in Klebsiella pneumoniae with ankylosing spondylitis patients and HLA-DR1/DR4 in Proteus mirabilis with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients.1-3 The influence of hormones can play a role, as seen with the onset or resolution of autoimmune disorders during menarche, pregnancy, lactation, and menopause. Toxicity can interfere with the deeper metabolic functions of the body, affecting the function of the immune system. And the genetic predisposition of an individual can set them up for susceptibility of developing autoimmune response unique to that individual’s triggers and patterning.

Daily lifestyle choices, including our relationship with food, exercise, and rest, are essential in maintaining health and wellness, thus preventing the initiation or the progression of autoimmune disorders. When these foundational aspects of our lives are in balance, the stress of daily life is more effectively managed, with stress being considered another triggering factor in the initiation of autoimmune disorders. Incorporating herbal medicine, in its many forms, can be an integral part of treatment. Whether using capsules, tinctures, infusions, decoctions, biotherapeutic drainage, gemmotherapy, flower essences, or essential oils, through addressing some of the above postulated etiologies, applied individually, the expression of the autoimmune disorder can be brought back into balance with the entire person.

Treatment

The elimination of toxins has a significant role in the treatment of autoimmune disorders, and herbal medicine can be incorporated according to the target organs and actions. For the liver/gallbladder, consider herbs that are bitters, cholagogues, choloretics, and alteratives/depuratives. Beginning gently may be necessary to avoid exacerbations. Diaphoretic herbs will enhance elimination through the skin, while liver herbs will support the liver detoxification pathways, taking the burden from the skin. Lymphagogue herbs work side by side with blood cleansers, filtering accumulated toxins from surrounding tissue. Galium aparine (cleavers), and Calendula officinalis (marigold), are 2 lymphagogues that can be used gently and over a long period of time. Castanea vesca (sweet chestnut), in the gemmotherapy extract, is a top lymphatic drainer. Diuretic herbs will enhance clearance through the urinary system, as well as assist in alkalinizing the body. Laxative herbs keep the colon moving effectively. Rhamnus purshiana (cascara sagrada), will enhance peristalsis and bring tone to the gut mucosa. Optimizing digestion, along with repair to the gut mucosa, can be supported through the use of probiotics, bitter herbs taken in small amounts before meals, warming aromatic herbs, and demulcents. The gemmotherapy Ficus carica (fig) should also be considered due to its ability to alter sympathetic dominance through disconnecting the firing between the cerebral cortex and the hypothalamus. Reestablishing function of the reticular endothelial system (RES), the phagocytic response, can be achieved using Rosa canina (dog rose) and Betula pubescens (downy birch), preferably in the gemmotherapy preparation.

One of the primary focal points in herbal therapy for autoimmune disorders is the inflammation-modulating herbs. Since excessive inflammation appears to be a significant contributing factor to diminished function and development of chronic disease, a closer look at some of the inflammation-modulating herbs could be useful. This article will highlight Boswellia serrata (frankincense), Curcuma longa (turmeric), Scutellaria baicalensis (huang qin or baical skullcap), Zingiber officinale (ginger), and Matricaria recutita (chamomile).

Boswellia serrata, Frankincense

Inflammation modulation, primarily through inhibition of the 5-lipoxygenase pathway, has shown efficacy in clinical trials for some autoimmune disorders, including RA, Crohn’s, ulcerative colitis, and bronchial asthma.4 The boswellic acids have been classified as selective, non-redox, and potent inhibitors of the biosynthesis of leukotrienes in vitro.5 The primary compound studied, acetyl 11-keto beta boswellic acid (AKBA), along with other compounds found in the resin, also show mast cell stabilizing activity.6

A group of Israel researchers reviewed a series of in vitro, in vivo, and clinical trials using Boswellia serrata resin. They found anti-inflammatory action through inhibition of NF-kappaB, as well as pro-apoptotic activity. In addition, it appears to have neuroprotective action and to support the mental and emotional aspect of disease through antidepressant and anxiolytic activity.7

Boswellia serrata is referred to by some as liquid sunshine. The flowing yellow essential oil, extracted from the golden hue resin, can be applied topically over inflamed joints. It warms the area and increases circulation to diminish swelling and pain. Boswellia is an underutilized herbal medicine with autoimmune conditions. Taken internally or applied topically, it can modulate the action of inflammation, diminishing the inflammatory products and their damage. In anthroposophic medicine, Boswellia extract, standardized to the AKBA compound, is combined with rhythmically prepared Boswellia serrata.

Curcuma longa, Turmeric

Found in the Zingiberaceae family, the same family as ginger, Curcuma longa’s inflammation-modulating effects are through inhibition of lipoxygenase (LOX), cyclooxygenase (COX), and other indicators of inflammation.8 Differing from its cousin, Zingiber officinale, turmeric is a cooling herb.

On its own, the absorption of turmeric in the gut is minimal.9 In the traditional use of turmeric as part of a curry mixture in food preparation, the other herbs enhance its absorption. In supplement form, combining Curcuma longa with bromelain, Piper nigrum (black pepper), or phosphatidyl choline are thought to increase bioavailability and absorption.

Trials have been done using Curcuma longa in combination with Boswellia serrata, Zingiber officinale, and Withania somnifera, all showing symptom improvement of RA and osteoarthritis (OA).10,11

Scutellaria baicalensis, Huang Qin or Baical Skullcap

This Lamiaceae family plant is bitter and cooling. In Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), it clears heat and dries dampness, particularly in the stomach and intestines, which can be a focal point in resolving the root of many inflammatory conditions.12 Some mechanisms of inflammation modulation of Scutellaria baicalensis root are the diminishment of NF-kappaB, the inhibition of prostaglandin and leukotriene production, and the binding of pro-inflammatory chemotactic cytokines.13-15

In addition to the inflammation modulating action, baical skullcap can be antibacterial, antiviral, and antifungal.16 This can prove useful in treating autoimmune disorders due to the potential triggering of the immune system as a result of these microbial infections.

Although combining baical skullcap in formula with warming herbs assists in balancing the cooling action, according to TCM it is contraindicated in cold conditions and deficient spleen or stomach patterns.12

Zingiber officinale, Ginger

The rhizome of Zingiber officinale, in its various herbal preparations, has been shown to inhibit 5-LOX, COX-1, COX-2, NF-kappaB, and thromboxane synthetase, modulating the many pathways of inflammation.17,18

Ginger is warming and increases circulation. The pungent taste and action comes from the active compounds gingerols, found in higher levels in the fresh rhizome, and shogaols, found in higher levels in the dry herb.19 The dry ginger increases heat to the core of the body, while the fresh ginger increases circulation to the periphery. Topical application will also increase circulation and modulate inflammation.

Zingiber officinale goes beyond inflammation modulation in its healing actions. It works through the GI tract, stimulating digestive function, a major focal point in the treatment of autoimmune disorders. It has antimicrobial action, abates nausea (for some people), is a diaphoretic, and an antispasmodic. It can be varied in its medicinal delivery, as a food, in a tea, tincture, capsule, and even as candied ginger.

Matricaria recutita, Chamomile

German chamomile has shown inflammation-modulating effects when taken internally. Diminished NF-kappaB production was shown through inhibition of COX-2, LOX, prostaglandins, and leukotrienes.20 Topical applications, however, are more prevalent in the literature. One German trial compared topical chamomile cream to steroid and non-steroid topical agents for eczema, showing equal effectiveness.21 The blue essential oil, chamazulene, along with matricin, alpha bisabolol and bisabolol oxides, are the inflammation-modulating components of Matricaria recutita.22

Chamomile was used for tummy aches in the Peter Rabbit children’s books, depicting its effects in aiding digestion. Containing mild bitter compounds and a spasmolytic action, it is used for dyspepsia, flatulence, and to quiet the cramping of colic. Chamomile also has antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anxiolytic properties. A cup of chamomile tea, often taken with a little honey, can quiet excessive sympathetic dominance, allowing the parasympathetic nervous system to promote better digestive function. An allergic histamine-type reaction related to Asteraceae family sensitivity has been noted in some people.23

Although herbal medicine can be effective in the treatment of autoimmune disorders, consider herbs to be just one tool in your toolbox of naturopathic medicine to help each individual reestablish the balance within their immune function and within their whole complex self.

Some herbs that support elimination and clearing in varying manifestations of autoimmune disorders:

Skin:

- Articum lappa, Burdock

- Berberis aquifolium, Oregon grape

- Scrophularia nodosa, Figwort

- Fumaria officinalis, Fumitory

- Galium aparine, Cleavers

- Solidago spp, Goldenrod

- Taraxacum officinale, Dandelion

- Trifolium pratense, Red Clover

- Urtica dioica, Nettles

Joints:

- Apium graveolens, Celery (seed)

- Arctostaphylos uva ursi, Knicknick

- Betula spp, Birch

- Gaultheria procumbens, Wintergreen

- Trifolium pratense, Red Clover

- Menyanthes trifoliate, Bogbean

- Populus spp, Poplar

- Salix spp, Willow

Lungs:

- Inula helenium, Elecampane

- Eriodictyon californicum, Yerba Santa

Bowels:

- Juglans regia, Walnut

- Rumex crispus, Yellow Dock

Gut:

- Aloe barbadensis, Aloe vera

- Calendula officinalis, Marigold

- Dioscorea villosa, Wild Yam

- Filapendula ulmaria, Meadowsweet

- Matricaria recutita, Chamomile

- Symphytum officinale, Comfrey

- Myrica cerifera, Bayberry

- Ulmus rubra, Slippery Elm

- Hamamelis virginiana, Witch Hazel

Robin DiPasquale, ND, RH(AHG) earned her degree in naturopathic medicine from Bastyr University in 1995 where, following graduation she became a member of the didactic and clinical faculty. For the past eight years she has served at Bastyr as department chair of botanical medicine, teaching and administering to both the naturopathic program and the bachelor of science in herbal sciences program. Dr. DiPasquale is a clinical associate professor in the department of biobehavioral nursing and health systems at the University of Washington in the CAM certificate program. She loves plants, is published nationally and internationally, and teaches throughout the U.S. and in Italy on plant medicine. She is an anusara-influenced yoga instructor, teaching the flow of yoga from the heart. She currently has a general naturopathic medical practice in Madison, Wis., and is working with the University of Wisconsin Integrative Medicine Clinic as an ND consultant.

Robin DiPasquale, ND, RH(AHG) earned her degree in naturopathic medicine from Bastyr University in 1995 where, following graduation she became a member of the didactic and clinical faculty. For the past eight years she has served at Bastyr as department chair of botanical medicine, teaching and administering to both the naturopathic program and the bachelor of science in herbal sciences program. Dr. DiPasquale is a clinical associate professor in the department of biobehavioral nursing and health systems at the University of Washington in the CAM certificate program. She loves plants, is published nationally and internationally, and teaches throughout the U.S. and in Italy on plant medicine. She is an anusara-influenced yoga instructor, teaching the flow of yoga from the heart. She currently has a general naturopathic medical practice in Madison, Wis., and is working with the University of Wisconsin Integrative Medicine Clinic as an ND consultant.

References

- Ebringer A, Ahmadi K, Fielder M, et al. Molecular mimicry: the geographical distribution of immune responses to Klebsiella in ankylosing spondylitis and its relevance to therapy. Clin Rheumatol. 1996;15(supp 1);57-61.

- Tiwana H, Wilson C, Cunningham P, Binder A, Ebringer A. Antibodies to four gram-negative bacteria in rheumatoid arthritis which share sequences with the rheumatoid arthritis susceptibility motif. Br J Rheumatol. 1996;35(6):592-594.

- Albani S, Carson DA. A multistep molecular mimicry hypothesis for the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. Immunol Today. 1996;17(10):466-470.

- Ammon HP. Boswellic acids in chronic inflammatory diseases. Planta Med. 2006;72(12):1100-1116.

- Wildfeuer A, Neu IS, Safayhi H, et al. Effects of boswellic acids extracted from a herbal medicine on the biosynthesis of leukotrienes and the course of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Arzneimittelforschung. 1998;48(6):668-674.

- Pungle P, Banavalikar M, Suthar A, Biyani M, Mengi S. Immunomodulatory activity of boswellic acids of Boswellia serrata Roxb. Indian J Exp Biol. 2003;41(12):1460-1462.

- Moussaieff A, Mechoulam R. Boswellia resin: from religious ceremonies to medical uses; a review of in-vitro, in-vivo and clinical trials. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2009;61(10):1281-1293.

- Chainani-Wu N. Safety and anti-inflammatory activity of curcumin: a component of turmeric (Curcuma longa). J Altern Complement Med. 2003;9(1):161-168.

- Sharma RA, McLelland HR, Hill KA, et al. Pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic study of oral Curcuma extract in patients with colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7(7):1894-1900.

- Kulkarni RR, Patki VP, Jog VP, Gandage SG, Patwardhan B. Treatment of osteoarthritis with an herbomineral formulation: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over study. J Ethnopharmacol. 1991;33(1-2):91-95.

- Chopra A, Lavin P, Patwardhan B, Chitre D. Randomized double blind trial

- Bensky D, Gamble A. Chinese Herbal Medicine Materia Medica. Seattle, Wash: Eastland Press; 1986.

- Huang KC. The Pharmacology of Chinese Herbs. 2nd ed. New York, NY: CRC Press LLC; 1999:385-386,400-401.

- Kimura Y, Okuda H, Arichi S. Effects of baicalein on leukotriene biosynthesis and degranulation in human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1987;922(3):278-286.

- Li BQ, Fu T, Gong WH, et al. The flavonoid baicalin exhibits anti-inflammatory activity by binding to chemokines. Immunopharmacology. 2000;49(3):295-306.

- Blaszczyk T, Krzyzanowska J, Lamer-Zarawska E. Screening for antimycotic properties of 56 traditional Chinese drugs. Phytother Res. 2000;14(3):210-212.

- Srivastava KC, Mustafa T. Ginger (Zingiber officinale) and rheumatic disorders. Med Hypotheses. 1989;29(1):25-28.

- Thomson M, Al-Qattan KK, Al-Sawan SM, Alnaqeeb MA, Khan I, Ali M. The use of ginger (Zingiber officinale Rosc.) as a potential anti-inflammatory and antithrombotic agent. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2002;67(6):475-478.

- Suekawa M, Ishige A, Yuasa K, Sudo K, Aburada M, Hosoya E. Pharmacological studies on ginger. I. Pharmacological actions of pungent constitutents, (6)-gingerol and (6)-shogaol. J Pharmacobiodyn. 1984;7(11):836-848.

- Liang YC, Huang YT, Tsai SH, Lin-Shiau SY, Chen CF, Lin JK. Suppression of inducible cyclooxygenase and inducible nitric oxide synthase by apigenin and related flavonoids in mouse macrophages. Carcinogenesis. 1999;20(10):1945-1952.

- Aertgeerts P, Albring M, Klaschka F, et al. Comparative testing of Kamillosan cream and steroidal (0.25% hydrocortisone, 0.75% fluocortin butyl ester) and non-steroidal (5% bufexamac) dermatologic agents in maintenance therapy of eczematous diseases [in German]. Z Hautkr. 1985;60(3):270-277.

- Hormann HP, Korting HC. Evidence for the efficacy and safety of topical herbal drugs in dermatology: part I: anti-inflammatory agents. Phytomedicine. 1994;1(2):161-171.

- Subiza J, Subiza JL, Hinojosa M, et al. Anaphylactic reaction after the ingestion of chamomile tea: a study of cross-reactivity with other composite pollens. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1989;84(3):353-358.