Sussanna Czeranko, ND, BBE

The Allopaths have endeavored to cure sick humanity on the basis of the highly erroneous idea that man can change the laws of nature that govern our being, and cure the cause of disease by simply ignoring it. To cure disease by poisoning its symptoms is medical manslaughter.

Benedict Lust, 1918, p. 426Do you practice with the fundamentals or with the superfluous? Adjuncts have their place, but they cannot supplant the methods upon which the exalted reputation of naturopathy has been built.

E. W. Cordingley, 1929, p. 548We came out boldly with our ‘Back to Nature’ slogan but this battle cry that could, and would have carried us on to victory has long since been forgotten.

Herbert M. Shelton, 1921, p. 283

We do not remember the past as often as we should these days given the momentum, depth, and sometimes pernicious messages of change in healthcare; happily, our history will not let us easily forget our roots. As Toynbee has taught, history cycles back and repeats itself, reclaiming in our minds and hearts what is intrinsic to our philosophy and our origins (Urban, 1974). How often we hear it said that when we want to gain perspective and understanding of familiar patterns and cycles that envelop our personal and professional lives, we need only to check back on where we came from. The elders and pioneers have been here before and have much to teach us.

As modern NDs, we have to recognize essential signposts along our current professional formation trajectory. We need to be clear about that which mirrors the past and at the same time about what is propelling us into the uncertain competitive future of so-called integrated medicine. The literature about the early NDs provides abundant stories that quickly reminded me that history does indeed repeat itself. Some of us embrace the cross-pollination of allopathic medicine as a signal of our having finally gained some modicum of parity and equal footing; others, less enamored of that path, put their faith in traditional naturopathic practice and are wary of being labeled “green allopaths.” The literature reminds us that the NDs of a hundred years ago had similar questions and issues of professional identity when, for example, they increasingly encountered new emerging treatments and watched the unrelenting march of biomedicine committed to displacing them.

In that long-ago climate, just as today, many NDs were feeling as if they were losing sight of the traditional healing arts of naturopathy. One dimension of that confusing era was the proliferation of devices and concoctions of every persuasion and type, promising miraculous cures that taunted and distracted the early NDs and their patients much in the same way that modern biomedicine entices with its avalanche of direct-to-consumer pharmacology promotion and news of newer and better, albeit immensely expensive, medical instruments and technology.

As Cordingley reported in the early years of biomedicine’s assault on naturopathic medicine, “the result has been the piling up in the office of the physician of a myriad of mysterious looking appliances, some possessing definite adjunctive therapeutic worth, but the most of it none at all” (1929, p. 548). Shelton also saw NDs “stung by the progressive bee” (1921, p. 283) in their search for the latest and best with which to help their patients. No one wanted to be left out or to miss a valuable tool or new knowledge. The literature suggests that many early NDs, afraid to be dismissed as ineffective or old-fashioned, found that it was easier to adopt the latest and the most scientific wonders, only to be disappointed with those same new gadgets and miracle cures during the long run of healing and prevention. In Shelton’s opinion, for example, the clutter of devices and products was such that the naturopathic office became “warehouses or junk shops” (1921, p. 283). Naturopathic physicians risked forgetting and loving their roots.

In their adoptive measures to excel in patient care and to compete with their increasingly ascendant biomedicine detractors, the early NDs risked losing much of what defined them as NDs. As Shelton writes, “we have lost sight of those great laws of Nature upon which we first [built]; we have turned away from our unifying principles” (1921, p. 283). Even so, there were enough NDs of the era who followed Hippocrates’ principle of “nature cures, not the physician” (Schultz, 1908, p. 342) that the principles lived on, cycling back into modalities and treatment protocols, into statements of philosophy and professional identity. Central to these enduring conversations was another resolute law that permeates naturopathic literature of this period, iterated often by Lindlahr: “the primary cause of disease is the violation of Nature’s Law” (1910, p. 33).

The erosion and, in all too many cases, the outright abandonment of nature and her wisdom were two edges of a broad assault on the roots of naturopathic medicine. Essentially, this erosion and departure were a mistake that we do not have to continue to make. Shelton writes: “…we need to come to a realization of the fact that the body restores itself to normal by identically the same process by which it was first built and maintained, that regeneration and healing take place in the cells and that these cells are constantly and ceaselessly striving with might and main, night and day, asleep or awake, every minute of our lives, to restore and maintain the normal” (1921, p. 287).

Rene Thirion comments: “nature cure does not suppress disease, nor merely counteract symptoms; it restores health through the regulation of body functions, by eliminating disease products and disease cause; in other words, by establishing a process of reconstruction and regeneration in the body” (1918, p. 275). Shelton, in this connection, differentiates between nature cure and other medical systems. In his view, all other systems (drug and drugless) are “only methods of ‘entertaining the patient while Nature restores him to health’ and are destructive. Nature Cure, on the other hand, is the art and science of supplying Nature with the conditions necessary to a cure and is constructive” (Shelton, 1923, p. 186).

Brook wrote about this very point a decade and a half earlier: “Disease is not, as is commonly supposed, an enemy at war with the vital powers, but a remedial effort—a process of purification and reparation. It is not a ‘thing’ to be destroyed, subdued or suppressed, but an action to be regulated and directed” (1908, p. 335).

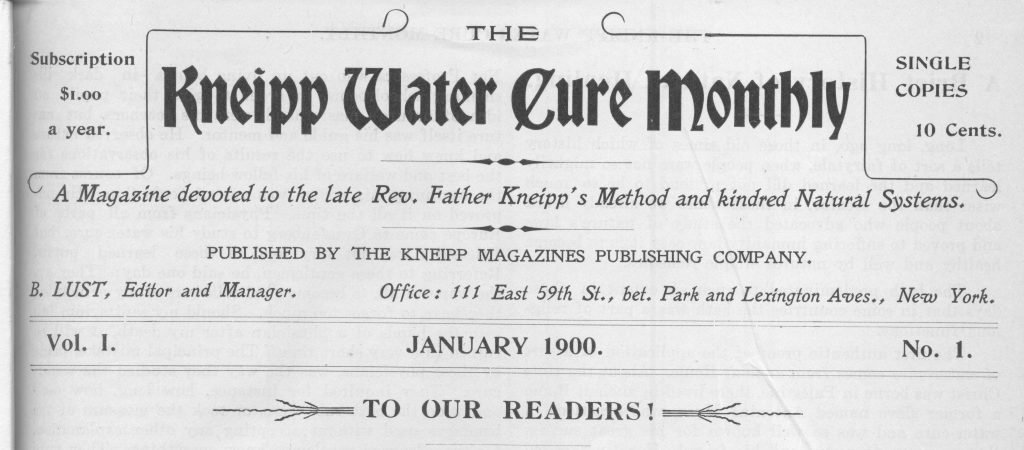

Cordingley, a contemporary of Shelton, wrote in 1929: “When Dr. Lust mounted the platform and lectured about the tried and proven methods of Kneipp, Preissnitz, Rickli, Just, Kuhne, and other eminent predecessors it was whispered about that those methods were all right fifty years ago, but they represented too much work for the modern healer who can hook up his patient to a machine whose ‘insides’ look like a lawn mower and let it do the work” (p. 548). Cordingley was prescient in foreshadowing the trend we see persisting today as some of us opt for the latest formularies, vaccines, and antibiotics.

The abandonment of nature cure in favor of “superstitions” was voiced by Bernard at about the same time. He wrote: “unfortunately, as human civilization grows up, it brings with it many of its ancient superstitions and fallacies” (Bernard, 1923, p. 401), constituting a culture of “vicarious redeemers.” Benedict Lust agreed with this sentiment:

Medical science has always believed in the superstition that the use of chemical substances which are harmful and destructive to human life will prove an efficient substitute for the violation of laws, and in this way encourages the belief that a man may go the limit in self indulgence that weaken and destroy his physical system, and then hope to be absolved from his physical ailments by swallowing a few pills, or submitting to an injection of a serum or vaccine, that are supposed to act as vicarious redeemers of the physical organism and counteract life-long practices that are poisonous and wholly destructive to the patient’s well-being. (Lust, 1918, p. 423)

Herbert Shelton spoke at length of modern medicine’s fascination with the promises of health, despite “sensuality, gluttony, inebriety, unclean living, lack of self control” (1922, p. 223). He pointed his finger at both allopathic and drugless practitioners, whom he contended were guilty of transgressing nature’s laws. He asserted at the time: “Modern medicine (drug and drugless) is still floundering around in the murky waters of alchemy. Both professions are constantly seeking for philosopher’s stone and an elixir vitae and ceaselessly do they bring in their new cures. But nature has never worked that way. She demands obedience to her laws and will accept no substitute for obedience” (Shelton, 1922, p. 225).

As defined by the early NDs, science was “systematized common sense, or systematized knowledge of Nature” (Bernard, 1923, p. 401). The NDs argued: “Nature Cure or Naturopathy, includes all rational means of aiding nature to throw off the impurities in the system, which constitute sickness. It includes the use of light, air and water baths, heat and cold, exercise, rest, non-stimulating diet, electricity, magnetism, massage, mental suggestion, osteopathy and chiropractic” (Schultz, 1908, p. 342).

Despite the mounting professional debate to the contrary, Bernard was optimistic that naturopathy would become “the basis of all future curative and preventive teachings” (1923, p. 401). The medicine that early NDs envisioned held Mother Nature very close. Today, we put these into a category of lifestyle modifications, about which perspective Lust had this to say: “The natural system for curing disease is based on a return to nature in regulating the diet, breathing, exercising, bathing and the employment of various forces to eliminate the poisonous products in the system, and so raise the vitality of the patient to a proper standard of health” (1918, p. 424).

Given the growth of naturopathic medicine since the early 1970s, we have without doubt come a long way. In 2011, the naturopathic profession is 110 years old. We have accumulated and codified much knowledge that continues to be published widely in such forms as the Foundations of Naturopathic Medicine Project (http://www.foundationsproject.com/) and in journals on both sides of the Atlantic and the Pacific. We have gained prescription rights in many states and provinces, affirming parity with our MD colleagues. The early NDs were wary of such “integration,” as we also should be. When we include self-identified integrative MDs at our conferences, as a profession we are standing as equals next to those biomedicine colleagues.

At the same time, there are many of us in practice who are less enthralled with this movement, worried that it is a form of co-opting, a patina, and eventually a process of assimilation of some of our modalities, values, and philosophical principles. Clauson witnessed the pilfering of naturopathic modalities in 1910, as he sounded the alarm: “When a new natural method of healing springs up, it is ridiculed by the ‘regulars’ but as soon as laymen begin to believe in this same method and demand its application, the medics at once seize upon it, transplant it to their own soil; proclaim it as their own ‘new discovery’ and proceed to practice it without preparation in a school which teaches natural methods. They seem to think that ‘natural things’ are so simple as to be acquired without any special training, when as a matter of fact our system is quite complicated” (p. 514).

Naturopathy, steeped in common sense and natural methods, has offered patients hope. We have successfully treated patients who have found naturopathy to be their preferred or even last option.

It behooves us to continue to learn from those who have gone before us: “Let us turn again the pages of the texts of Kneipp, of Bilz and of Kuhne and read their case histories. Let us look again at the ‘incurables’ of the last century who found health at the hands of our pioneers after other methods had failed” (Cordingley, 1929, p. 549).

Sussanna Czeranko, ND, BBE, is a faculty member working as the Rare Books Curator at National College of Natural Medicine. She is currently compiling several books based on the journals published by Benedict Lust. In addition to her work in balneotherapy, she is the founder of the Buteyko Breathing Academy, a training program for NDs to incorporate a scientific model of breathing therapy called Buteyko into their practice.

Sussanna Czeranko, ND, BBE, is a faculty member working as the Rare Books Curator at National College of Natural Medicine. She is currently compiling several books based on the journals published by Benedict Lust. In addition to her work in balneotherapy, she is the founder of the Buteyko Breathing Academy, a training program for NDs to incorporate a scientific model of breathing therapy called Buteyko into their practice.

References

Bernard, B. (1923). Nature is the healer of all diseases. The Naturopath and Herald of Health, 28(8), 401-402.

Brook, H. (1908). The “nature cure.” The Naturopath and Herald of Health, 9(11), 335-340.

Clauson, J. A. (1910). The dawn of a new era: A farewell address to American School of Naturopathy. The Naturopath and Herald of Health, 15(10), 514-516.

Cordingley, E. W. (1929). Fundamental naturopathy. Nature’s Path, 34(11), 548-549.

Lindlahr, H. (1910). Catechism of nature cure. The Naturopath and Herald of Health, 15(1), 30-35.

Lust, B. (1918). The principles, aim and program of the nature cure system. Herald of Health and Naturopath, 23(5), 423-429.

Schultz, C. (1908). An open letter to the public. The Naturopath and Herald of Health, 9(11), 342-343.

Shelton, H. M. (1921). What have we? Nature cure or a bag of tricks? Herald of Health and Naturopath, 26(6):283-287.

Shelton, H. M. (1922). Nature as a bill collector. Herald of Health and Naturopath, 27(5):223-225.

Shelton, H. M. (1923). Essentials of nature cure. Herald of Health and Naturopath, 28(4):181-186.

Thirion, R. V. (1918). Naturopathy or nature cure. Herald of Health and Naturopath, 23(3), 275-277.

Urban, G. R. (1974). Toynbee on Toynbee: a conversation between Arnold J. Toynbee and G. R. Urban. New York: Oxford University Press.