Hanna Ian, MS, NMD

I will never forget the first time I observed the excision and drainage of a perianal cyst. The pain, pressure, and putrefactive pus, followed by packing and patch-up, left an indelible mark in my memory. While frequently referenced as an epidermoid cyst, a sebaceous cyst, or an abscess, the official disease nomenclature is hidradenitis suppurativa (HS). With a desire to spare my patients the dysbiotic sequela of systemic antibiotic therapy and recovery from an excision and drainage, naturopathic care as a first-line treatment of stage 1 HS has proven extraordinarily successful among my patients. Following is a brief review of the pathogenesis of the disease.

Hidradenitis suppurativa manifests as a solitary lesion or as multiple lesions, exquisitely painful to touch or pressure, with inflammation, edema, and pus formation; the lesions range from as small as a pea to as large as a baseball. Areas commonly affected have high concentrations of apocrine sweat glands such as the axillae, groin, and perianal region.1 If chronic and unresolved, the lesions may form sinus tracts or tunnels connecting the abscesses, with the possibility of the development of a fistula to the surface of the skin to facilitate drainage.

Etiology

Hidradenitis suppurativa is not caused by bacteria of any kind. The prevailing theory of the etiology of HS is that apocrine glands become blocked with fluid and dead skin cells mixed with additional debris from surrounding sebaceous glands.2 Recent research has identified HS as a disorder of follicular occlusion rather than apocrine occlusion, with secondary involvement of apocrine glands.3 Whether plugging originates in the hair follicle or in the apocrine gland, the initial inflammatory event leads to the rupture of the follicular epithelium. The cause of the rupture is unknown; however, friction in the intertriginous areas is thought to be a contributing factor.

Following the rupture, foreign body material spills into the dermis, cascading the inflammatory response with the resulting granuloma formation. Epithelial strands create draining sinus tracts in the inflamed tissue. Colonization with bacteria, usually coagulase-negative staphylococci, exacerbates the inflammation, contributing to chronic infection.4

Diagnosis

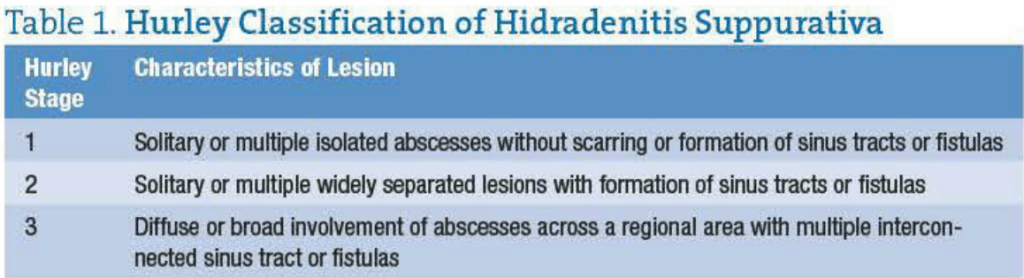

Clinical findings are the basis of diagnosis of HS, and a biopsy is rarely required. Three key elements are needed for the diagnosis of HS: the characteristics of the lesion, the pattern of distribution, and the recurrence. The characteristics of the lesion have been staged into 3 groups (Hurley classification) based on the presence and extent of sinus tract formation (Table 1).5

Hidradenitis suppurativa most frequently occurs in areas where folds of skin (intertriginous) are present, including the axillae, between the buttocks, between the scrotum and the thigh, or beneath pendulous breasts. However, other areas with high concentrations of terminal hair follicles and apocrine sweat glands can also be affected such as the areola of the breast, the periumbilical region, the scalp, the zygomatic and malar areas of the face, and the nape of the neck, as well as the external auditory meatus.

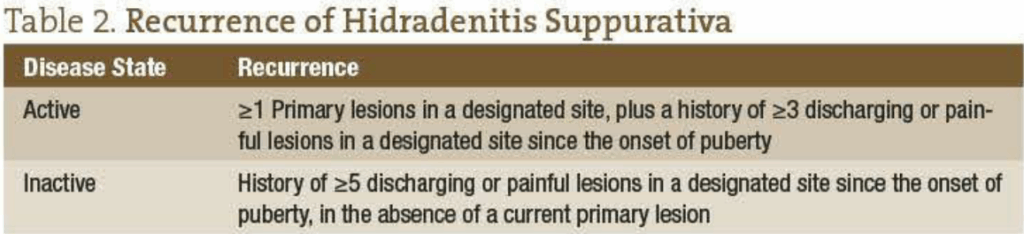

The recurrence of HS can best be evaluated using 2 criteria for active disease or inactive disease.6 This is summarized in Table 2.

Epidemiology

Hidradenitis suppurativa occurs in 1% to 2% of the general population in the United States7 and accounts for an average loss of 2.7 workdays per year.8 There are considerable differences in occurrence between the genders, with women experiencing HS 2 to 5 times more frequently than men.6 Gender differences are also seen in the location of the lesions, with genitofemoral lesions occurring more in women and perianal lesions manifesting more commonly in men. The average age at onset of HS is 23 years, with the age at onset ranging from 11 to 50 years.9 It rarely occurs before puberty10 or after menopause.11

HS and Women’s Health

In relation to women’s health, apocrine glands are stimulated by androgen and are suppressed by estrogen.12 Many women report flair-ups of HS occurring at the onset of menses. Others report a temporary cessation of HS with pregnancy, followed by flair-ups with the return of menses. In considering the estrogenic influence on inflammation, this could suggest how low levels of estrogen contribute to the onset or recurrence of the disease.13

Hirsutism and obesity can be comorbid occurrences among women with HS.14 Obesity alters sex hormone metabolism, causing a state of androgen excess. The excess androgens lead to an increase in keratin production and the coarsening of the hair shaft, both of which can contribute to follicular occlusion.15

Allopathic Treatment

Allopathic Treatment

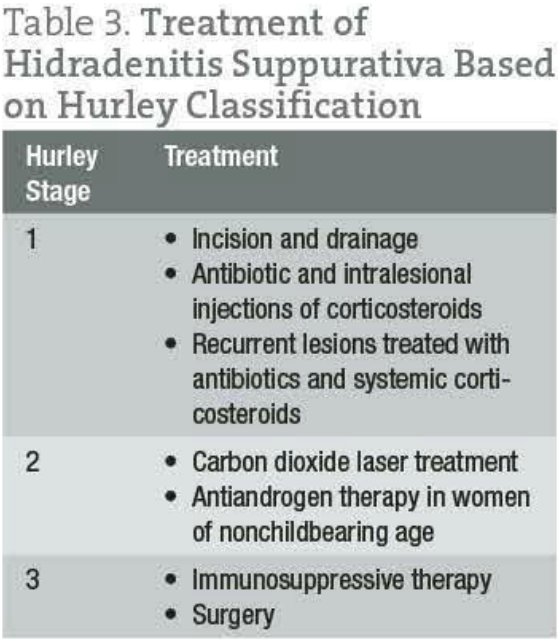

The allopathic treatment of HS is considerably challenging as systemic antibiotics and repeated incision and drainage produce only short-term relief, with the unavoidable end result of more inflammation.16 Medical management, however, is recommended as early as possible, with treatment individualized according to the stage and extent of the disease. Treatment algorithms based on the Hurley classification provide the basis for the standard of care (Table 3).17

Other allopathic approaches to the treatment of HS include oral retinoid medications, androgen-blocking drugs, monoclonal anti–tumor necrosis factor antibodies, electrocoagulation of sinus tracts, cryotherapy, and carbon dioxide laser surgery, followed by skin grafting.18-21 In one study,6 nearly one-quarter of patients reported experiencing no successful outcome with any therapeutic measure, including surgery, despite an average disease duration of 19 years. While the outcomes of the study indicated that available treatments are unsatisfactory for some patients, the results also provide an open invitation for effective naturopathic care for HS in Hurley stage 1.

Naturopathic Treatment Modalities for Hurley Stage 1

Hydrotherapy

Intense moist heat applied locally for several minutes can penetrate tissues at a depth of 3.4 cm. Heat causes vasodilation in local tissues, which results in increased arterial and venous capillary pressure, as well as oxygen-carrying capacity. In addition, vasodilation has beneficial effects on the metabolic activity and the migration of lymphocytes through vessel walls to the site of infection.22

Oil of Oregano

Historical use of oil of oregano as an antimicrobial agent dates back to ancient Egypt and the Roman Empire. At the turn of the 20th century, oil of oregano was believed to be 26 times more active as an antiseptic than phenol. In 1910, hospitals put the powerful disinfectant properties of oil of oregano to use in the sterilization of equipment.23

In contemporary science, there is a considerable body of evidence for the support of oregano oil as a valuable antibiotic. Oil of oregano may be an effective treatment against drug-resistant bacterial infections and appears to reduce bacterial infection as effectively as traditional antibiotics.24 Oil of oregano at relatively low doses was found to be efficacious against Staphylococcus bacteria and was comparable in its germ-killing properties to antibiotic drugs such as streptomycin sulfate, penicillin, and vancomycin.25 Among 52 plant oils tested, oregano was considered to have pharmacologic action against Candida albicans, Escherichia co li, Salmonella enterica, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa.26 Researchers at the Department of Food Science and Technology at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, reported that among various plant oils oil of oregano exhibited the greatest antibacterial action against common pathogenic germs such as Staphylococcus, E coli, and Listeria.27 British researchers also have reported that oregano oil had antibacterial activity against 25 different bacteria.28 Additionally, carvacrol from oil of oregano has been found to kill the resistant spores of Bacillus cereus and Bacillus anthracis.29

li, Salmonella enterica, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa.26 Researchers at the Department of Food Science and Technology at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, reported that among various plant oils oil of oregano exhibited the greatest antibacterial action against common pathogenic germs such as Staphylococcus, E coli, and Listeria.27 British researchers also have reported that oregano oil had antibacterial activity against 25 different bacteria.28 Additionally, carvacrol from oil of oregano has been found to kill the resistant spores of Bacillus cereus and Bacillus anthracis.29

Oil pressed from the leaves of Origanum vulgare contains the active ingredient carvacrol, which has the capacity and affinity to combat bacterial infections of the mucous membranes. Within the field of naturopathic medicine, oil of oregano is regarded by some as the “Rolls-Royce” of natural antiseptics. In comparing the antimicrobial properties of oil of oregano with other medicinal botanicals, oil of oregano is considered more active against noxious urinary pathogens than garlic, goldenseal, and echinacea.30

It is important to note that oil of oregano is contraindicated in patients with known allergies to thyme, basil, mint, sage, or oregano. Due to its action as a uterine stimulant, it is contraindicated in pregnancy. Oil of oregano also has anticoagulant properties and as such is contraindicated in patients taking warfarin sodium or other anticoagulant drugs.

Other Antimicrobial Botanicals

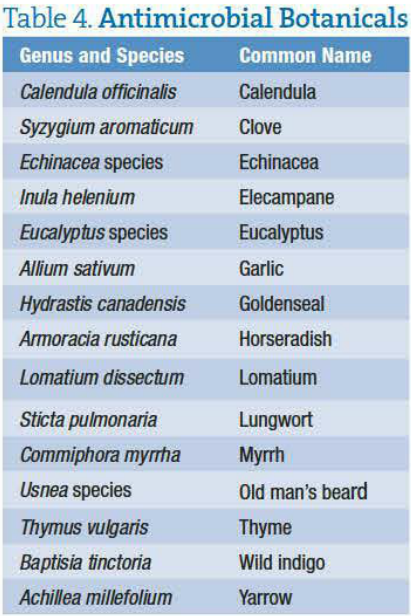

The ability of botanicals to destroy or suppress the growth of bacteria is well known in the naturopathic literature. Examples of antimicrobial botanicals are given in Table 4 and can be taken as a tincture or in encapsulated forms. The reader is encouraged to consult botanical references for properties that would be most appropriate for their individual patients.

Naturopathic Treatment Plan for Genitofemoral or Perianal Lesions of Hurley Stage 1 HS

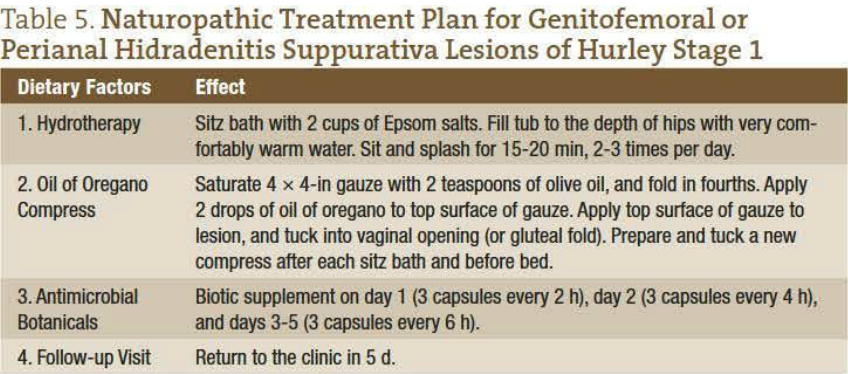

Following is a naturopathic treatment plan for genitofemoral or perianal HS lesions in Hurley stage 1. Table 5 summarizes the treatment plan.

The Right Choice

In encouraging active participation in one’s treatment, I present for my patients’ consideration 2 therapeutic options, each with its advantages and disadvantages: (1) antibiotic therapy with a topical corticosteroid ointment or (2) the naturopathic treatment plan outlined herein. In all cases seen in my practice, patients have elected to use the naturopathic modalities of hydrotherapy, combined with a compress of oil of oregano and additional antimicrobial botanicals. If at the 5-day follow-up visit there has been a less than desirable resolution to the lesion, antibiotic therapy can be used as the next course of action. However, in all cases I have found it unnecessary to proceed to antibiotic therapy as the exquisitely tender and swollen lesions resolve to the delight and amazement of my patients. Patients generally report a 60% improvement by day 3, a 75% to 80% improvement by day 4, and a 90% to 98% improvement at the 5-day follow-up visit.

The Last Word

Trust in vis medicatrix naturae!

Dr Hanna Ian, MS, NMD, brings over twenty years experience in the fields of public health, clinical nutrition and women’s health, along with an extraordinary combination of skills, knowledge and sharp perception to her medical practice. She has served on the public health faculty of Southern Connecticut State University as well as Patient Educator for the Department of Obstetrics at Yale-New Haven Medical Center. She is the former Medical Director of Brookfield Integrative Medicine in Brookfield, Wisconsin. Dr. Ian is a spokesperson for the American Cancer Society where she lectures on breast health and breast cancer prevention.

Dr Hanna Ian, MS, NMD, brings over twenty years experience in the fields of public health, clinical nutrition and women’s health, along with an extraordinary combination of skills, knowledge and sharp perception to her medical practice. She has served on the public health faculty of Southern Connecticut State University as well as Patient Educator for the Department of Obstetrics at Yale-New Haven Medical Center. She is the former Medical Director of Brookfield Integrative Medicine in Brookfield, Wisconsin. Dr. Ian is a spokesperson for the American Cancer Society where she lectures on breast health and breast cancer prevention.

References

- Freedberg IM, Goldsmith LA, Katz S, Austen KF, Freedberg KW, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 6th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2003.

- Shelley WB, Cahn MM. The pathogenesis of hidradenitis suppurativa in man: experimental and histologic observations. AMA Arch Derm. 1955;72(6):562-565.

- Yu CC, Cook MG. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a disease of follicular epithelium, rather than apocrine glands. Br J Dermatol. 1990;122(6):763-769.

- Lapins J, Jarstrand C, Emtestam L. Coagulase-negative staphylococci are the most common bacteria found in cultures from the deep portions of hidradenitis suppurativa lesions, as obtained by carbon dioxide laser surgery. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140(1):90-95.

- Hurley HJ. Axillary hyperhidrosis, apocrine bromhidrosis, hidradenitis suppurativa and familial benign pemphigus: surgical approaches. In: Roenigk RK, Roenigk HH, eds. Dermatologic Surgery: Principles and Practice. New York, NY: Marcel Dekker; 1989:729-739.

- von der Werth JM, Jemec GB. Morbidity in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144(4):809-813.

- Jemec GB, Heidenheim M, Nielsen NH. The prevalence of hidradenitis suppurativa and its potential precursor lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35(2, pt 1):191-194.

- Jemec GB, Heidenheim M, Nielsen NH. Hidradenitis suppurativa: characteristics and consequences. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1996;21(6):419-423.

- Brown TJ, Rosen T, Orengo IF. Hidradenitis suppurativa. South Med J. 1998;91(12):1107-1114.

- Weber-LaShore A, Huppert JS. Hidradenitis suppurativa in a pre-pubertal female. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2009;22:e53.

- Barth JH, Layton AM, Cunliffe WJ. Endocrine factors in pre- and postmenopausal women with hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134(6):1057-1059.

- Wiseman MC. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a review. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17(1):50-54.

- Jemec GB. Hidradenitis suppurativa. J Cutan Med Surg. 2003;7(1):47-56.

- Barth JH. Cutaneous Virilism, Apocrine Glands and Hidradenitis Suppurativa [thesis]. London, England: University of London; 1992.

- Attanoos RL, Appleton MA, Douglas-Jones AG. The pathogenesis of hidradenitis suppurativa: a closer look at apocrine and apoeccrine glands. Br J Dermatol. 1995;133(2):254-258.

- Tanaka A, Hatoko M, Tada H, Kuwahara M, Mashiba K, Yurugi S. Experience with surgical treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa. Ann Plast Surg. 2001;47(6):636-642.

- Alikhan A, Lynch PJ, Eisen DB. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a comprehensive review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60(4):539-561.

- Mortimer PS, Dawber RP, Gales MA, Moore RA. A double-blind controlled cross-over trial of cyproterone acetate in females with hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 1986;115(3):263-268.

- Martínez F, Nos P, Benlloch S, Ponce J. Hidradenitis suppurativa and Crohn’s disease: response to treatment with infliximab. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2001;7(4):323-326.

- Bong JL, Shalders K, Saihan E. Treatment of persistent painful nodules of hidradenitis suppurativa with cryotherapy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28(3):241-244.

- Madan V, Hindle E, Hussain W, August PJ. Outcomes of treatment of nine cases of recalcitrant severe hidradenitis suppurativa with carbon dioxide laser. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159(6):1309-1314.

- Barry R. Hydrotherapy. In: Pizzorno JE, Murray MT, eds. Textbook of Natural Medicine. Vol 1. 3rd ed. St Louis, MO: Churchill Livingston; 2006:405.

- Ingram C. The Cure Is in the Cupboard: How to Use Oregano for Better Health. Vernon Hills, IL: Knowledge House Publishers; 2008.

- Faleiro L, Miguel G, Gomes S, et al. Antibacterial and antioxidant activities of essential oils isolated from Thymbra capitata L. and Origanum vulgare L. J Agric Food Chem. 2005;53(21):8162-8168.

- Preuss HG. Oregano oil may protect against drug-resistant bacteria. In: Proceedings from the Annual Conference of the American College of Nutrition (“Symposium on Advances in Clinical Nutrition”); October 3-7, 2001; Orlando, FL.

- Hammer KA, Carson CF, Riley TV. Antimicrobial activity of essential oils and other plant extracts. J Applied Microbiol. 1999;86:995-999.

- Elgayyar M, Draughon FA, Golden DA, Mount JR. Antimicrobial activity of essential oils from plants against selected pathogenic and saprophytic microorganisms. J Food Prot. 2001;64:1019-1024.

- Dorman HJ, Deans SG. Antimicrobial agents from plants: antimicrobial activity of plant volatile oils. J Appl Microbiol. 2000;88:308-316.

- Billing J, Sherman P. Antimicrobial function of spices: why some like it hot. Q Rev Biol. 1998;73:3-49.

- Potterton D. Kill and cure: the healing properties of wild oregano oil. Br Naturopathic J. 2001;18-23.