Nicole Cain, ND

Introductory Case: Laura’s Story

Eyes averted and hands clenched in her lap, Laura told me that I was the 12th doctor she had seen for her weight loss issues. She had tried intermittent fasting, juicing, cleanses, colonics, supplements, exercise, and dieting without success. She was referred to me because she also suffered from depression and anger, and her naturopathic doctor suspected a link between her weight and mood. Upon assessing Laura’s case, I learned that she had been morbidly obese since childhood, and now in her early 30s, she felt discouraged and hopeless. Further questioning revealed that she had been repeatedly sexually molested from infancy through adolescence and that though she really wanted to lose the weight, the benefit of being obese was that it made her feel unattractive and thus safe from unwanted attention.

Trauma Statistics

Research into the field of trauma has increased dramatically over the last decade. Trauma is a worldwide epidemic and is foundational to innumerable physiological and psychological maladies. According to a 1995 study conducted by Kessler et al, 56% of adults reported having experienced at least 1 traumatic event.1 Another study reported that 90% of patients who seek mental health services have been exposed to a traumatic event, and most of those patients reported having multiple experiences of trauma.2 Ninety-three percent of adolescents in inpatient settings have a history of trauma, 32% of whom have severe symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).3 The judicial system is also no stranger to trauma; a study conducted by Acoca and Dedel found that 92% of incarcerated girls reported sexual, physical, or severe emotional abuse in childhood.4

There is an important implication that can be drawn from these staggering statistics: It is absolutely essential to consider a trauma with every single patient in treatment.

During the period of 1995-1997, Robert F. Anda, MD, MS, (with the CDC) and Vincent J. Felitti, MD, (with Kaiser Permanente) joined forces in one of the largest investigations of the longitudinal effects of childhood trauma.5 They defined trauma as “an extreme stress that overwhelms a person’s ability to cope. The person reports a feeling of vulnerability, helplessness, and fear. This is severe enough to interfere with relationships and fundamental beliefs.” The study looked at what they called Adverse Childhood Events (ACE) in an estimated 17 000 persons. After the study was completed, results were analyzed, and have far-reaching implications for the fields of mental health and medicine, in general – indicative of a possible paradigm change, in terms of how many practitioners view mental and physical disorders and disease.

Below are several findings from their study:

- Adults with an ACE score of 4 or more were 460% more likely to be suffering from depression

- The likelihood of adult suicide attempts increased 30-fold, or 3000%, with an ACE score of 7 or more

- Childhood and adolescent suicide attempts increased 51-fold, or 5100%, with an ACE score of 7 or more

- A child with 6 or more categories of adverse childhood experiences is 250% more likely to become an adult smoker

- A person with 4 categories of adverse childhood experiences is 260% more likely to have chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

- A 500% increase in adult alcoholism is directly related to adverse childhood experiences. Two-thirds of all cases of alcoholism can be attributed to adverse childhood experiences

- Additional elucidated correlations have been found between increased ACE scores and bone fractures, liver disease, fetal death, early death, and more

The Biology of Trauma

For medical professionals, an important question becomes: What is the pathophysiology of the effects of trauma?

Dr Peter Lang7 and Daniel Amen8 are leading experts in the field, assessing the neuropathology of trauma. Dr Lang’s research on the psychobiology of trauma explains that synaptic connections are continually being formed throughout life, and that emotionally laden imagery correlates with measurable autonomic responses. Dr Lang proposed that emotional memories are stored in the brain as “associative networks,” which become activated when a person is confronted with situations that stimulate a number of elements that make up these networks. The more traumas a person is exposed to, the more elements are able to be stimulated, which indicates a greater trauma response.7

In short, trauma changes the brain. It changes the synaptic connections, the structure, and the way that the brain responds to stimuli in a person’s environment or their general thought processes. Focus plus repetition causes neuro-stem cells to differentiate and form distinctions in connectivity. Repeated focus reinforces neuro-pathways through thickening of myelin activity, which increases transmission speed. Dysregulation in associative networks causes changes in different parts of the brain, thereby producing different, observable symptoms.

The brain is responsible for production of serotonergic, opioid, dopaminergic, glutamatergic, thyroid, and gabaergic function. Dysregulation in the areas responsible for this production will result in abnormal and maladaptive functioning of these aspects of a patient’s physiology.

For example, the brain’s cortex is involved with emotional balance and regulation. It controls flexibility in reactivity, empathy, insight, discernment, the fear response, judgment, intuition, spiritual feelings, and the ability to be attuned to other people. Cortex dysregulation may therefore result in an imbalance in each of the previously-listed functions, as well as emotional regulation and flexibility, general regulation, and coordination.

The brain stem is involved in regulation of heart rate, blood pressure, body temperature, and respiration; it also stores memory called “state memory.”9 The brain stem also controls the production and release of some neurotransmitters. Brain stem dysregulation caused by changes in associative networks can therefore produce abnormalities in production and release of some neurotransmitters, which are associated with psychiatric disorders such as depression and psychosis. Dysregulation can also cause increased adrenocortical hormone release in blood, suppression in immune system function, changes in blood flow, and alterations in heart rate and respiration rate.

The research of Dr Lang (and others) has indicated that when the brain is dysregulated, imbalances in healthy neurotransmitters and hormone production can occur. Key neuroendocrine abnormalities found in patients who have suffered from trauma include: alterations in catecholamines,10 corticosteroids,11 sterotonin,10 and endogenous opioids.12,13 This may result in a number of disease states such as obesity, depression, anxiety disorders, eating disorders, lethargy, random pains (eg, fibromyalgia), fatigue (chronic fatigue syndrome), and feelings of hopelessness.

Red Flags: Signs of Trauma

Many physicians are versed in the identification of classic symptoms associated with post-traumatic stress disorder (eg, flashbacks, nightmares, hyperarousal, emotional numbing, avoidance, and a heightened fear response), but what about patients who have a history of trauma yet do not appear to fit into the typical PTSD “box”?

Here are some symptoms to look out for, and points to keep in mind:

- Exposure to “anything that interrupts or interferes with normal social, emotional, psychological, cognitive, language or physical developmental processes can be considered traumatic”5

- Trauma can occur via: neglect, sanctuary, physical, emotional, exploitation, bullying, etc

- Look out for “ever since” statements: “I have been overweight since…” or “My chronic fatigue started when…” or “I have been unable to [insert activity] since….”

- Extreme and chronic anxiety, as well as phobias

- Difficulties concentrating because of intrusive thoughts and memories

Treatment Approaches to Trauma

First, have a foundation of understanding, in terms of the warning signs of a traumatic etiology in a patient’s symptoms. The next step is to understand the proper protocol for treating trauma. This will vary from case by case, and state by state. This article does not aim to be an all-inclusive triage for trauma but to provide general suggestions to get you started.

Step 1: Determine if the situation requires inpatient management, and refer accordingly (rule out risks of suicide and homicide). If you do not know the answer to this, you might call the National Suicide and Crisis Lifeline: In the United States, call 1-800-273-8255.14

Step 2: Determine if the patient is within your scope of competency and, if not, refer appropriately. The Suicide and Crisis Lifeline may assist you with this. Additional examples of referral sources include hospitals. If it is not an acute-management situation but the symptoms are outside of your scope of practice, it is recommended, for both you and the patient, that you to refer the patient to someone who has more experience with trauma.

Step 3: If you determine you are comfortable managing this patient, do not do it alone. Establish a treatment team. Locate appropriate mental-health and other community support resources (eg, counselor, psychiatrist, EMDR therapists) and other specialist practitioners in your local community. Also remember to take into consideration the patient’s family, friends, and social support resources. My treatment teams often include psychiatrists, counselors, or other specialists. A resource for trained EMDR practitioners nationwide may be found at www.EMDR.com.

Step 4: Obtain psychological assessment screening tools. Upon releasing the DSM5, the American Psychiatric Association also developed a number of screening tools that are useful companions to clinical diagnosis and assessment. They may be found on the American Psychiatric Association’s website.15 Otherwise, a referral to a behavioral psychologist may be appropriate.

Step 5: Develop a crisis intervention plan, including referral forms. This will become especially important as you assist your patient through the healing process. Regardless of the issue you may be working on with your patient (eg, weight loss, fibromyalgia, knee pain, or recurrent lung infections), as the patient’s body begins to heal, it is very possible that experiences and issues from the past trauma may begin to surface. Noticing these past trauma-related issues may dysregulate your patient. Having a plan set up in advance will assist in keeping the treatment process moving forward safely.

Step 6: Implement trauma therapies.

The Role of Naturopathic Medicine in Trauma

Naturopathic medicine provides unique and powerful treatment alternatives to conventional approaches to dealing with trauma. The standard of care for PTSD is counseling, as well as pharmacological interventions such as sertraline and paroxetine.16 Below are some approaches naturopathic doctors may take, with consideration to the Therapeutic Order:

- Address acute concerns: For example, crisis management and triage

- Set the foundation for health: Give the body what it needs. For example: Can the body methylate? Is the patient getting the proper nutrients for optimal physiological processes?

- Stimulate the vital force: My favorite way is through homeopathy

- Tonify weak and damaged systems: Neurobiology shows traumatized patients having altered cortisol production (whether abnormally elevated, shifted, or decreased); supporting this can help6

- Correct structural integrity: A publication from The Journal of Vertebral Subluxation demonstrated that 70% of participants showed a “marked improvement” on the Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI-II) scale post-upper cervical misalignment correction.17 Another study from the Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics on bipolar disorder, seizures, sleep disorders, and migraines showed significant trends of improvement post-manipulative corrections.18

- Address the disease and suppress the disease: Pharmaceutical interventions may be necessary. This also includes natural supplementation like anxiolytic herbs in the management of anxiety.

Remedy Selection

Laura laughed immoderately while she explained her symptoms, expressing that she felt like her molestation had actually been her fault. She felt incredible remorse, stating that she knew she owed her mother an apology for allowing the rapes to occur. She says that she has felt worthless her entire life and that the only way to prove she has any value is by working too much and too hard. Any lack of perfection is considered a failure, and her inability to lose weight is a demonstration of her worthlessness and failure. Though sometimes the depression would rear its ugly head, making her feel suicidal and despairing, most of the time she refused to think about it. She held her emotions in, and they would come out in bursts of violent anger. She could not tolerate being contradicted and this would lead to her berating her staff and even her boss. She was great at her job, but if someone pointed out something that was incorrect, she would fly into a rage.

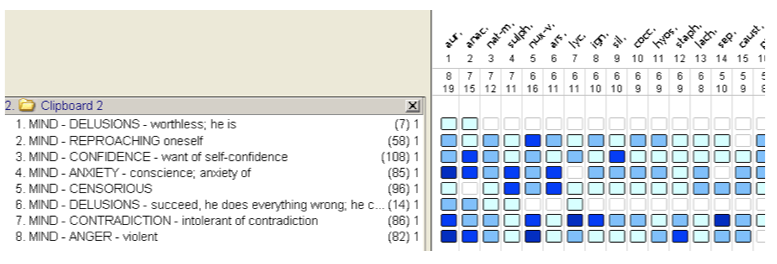

The 2 main symptoms in her case were the pathological guilt and the delusions of failure – that if she is not perfect, then she is a failure. Upon reading the materia medica, this was best covered by homeopathic Aurum metallicum (Figure 1). Aurum also covers the intolerance of contradiction. Natrum muriaticum was also a good consideration for her. I started her on Aurum metallicum and referred her for EMDR counseling with a practitioner that I trust.

The process of improvement in these cases is slow and long. You might not see overnight miracles. Remember, with longstanding trauma, the brain changes are deep and complex. However, as the trauma is dealt with and the brain starts to heal itself, the physiology will change as well. Laura is still working through her trauma, but with homeopathy and counseling, she is more emotionally stable. She is now empowered in her weight loss goals, and is already starting to see the first signs of success.

Understanding a Patient’s Past Can Help You Understand the Present

Naturopathic medicine is rooted in the Therapeutic Order, which looks at the entire gestalt of a patient. Whether you are focusing on mental health, pain, obstetrics, or urinary diseases, a solid foundation and competence in dealing with trauma will optimize your effectiveness as a physician. To learn more about trauma, and how it may present in your clinical practice, please refer to the references.

* Disclaimer: Name, age, and general information of the patient in the case have been edited and changed. Any resemblance to a person in this case is purely coincidental. This article is not intended to be a complete guide on assessment, triage, or management of trauma; it is intended for academic purposes only.

Nicole Cain, ND practices general family medicine, with a specialization in integrative approaches to mental health and with a particular focus in homeopathy. Dr Cain received her Doctorate of Naturopathic Medicine from the Southwest College of Naturopathic Medicine (SCNM), where she also completed an accredited residency. She has a graduate degree from The Chicago School of Professional Psychology (CSOPP) with an MA in clinical psychology, counseling specialization; there she received advanced training in the diagnosis and treatment of mental illness. She studied psychobiology and psychoneuroimmunology during undergraduate training at Luther College. Dr Cain has been published in a number of online journals and newspapers including, but not limited to, the Arizona Republic and SCNM Now. She is clinical and diadactic teacher of “Medical Psychology and Psychiatric Diagnosis and Treatment, and General Medicine” at SCNM. She is a board member of the Arizona Naturopathic Medical Association (AZNMA), co-founder of the not-for-profit establishment Homeopathic Medicine for Mental Health (HMMH), she sits on the board of directors for Fountainhead Naturopathic Medical Center of Santa Cruz, CA, and she is a medical consultant for the company, Orb Health.

References

- Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52(12):1048-1060.

- Mueser KT, Goodman LB, Trumbetta SL, et al. Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in severe mental illness. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1998;66(3):493-499.

- Lipschitz DS, Winegar RK, Hartnick E, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder in hospitalized adolescents: psychiatric comorbidity and clinical correlates. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38(4):385-392.

- Acoca L, Dedel K. No Place to Hide: Understanding and Meeting the Needs of Girls in the California Juvenile Justice System. July 17, 1998. National Council on Crime & Delinquency (NCCD) Web site. http://nccdglobal.org/publications/no-place-to-hide-understanding-and-meeting-the-needs-of-girls-in-the-california-juvenil. Accessed January 20, 2014.

- Anda R, Felitti VJ. The Adverse Childhood Experiences Study. Centers for Disease Control & Prevention Web site. http://www.cdc.gov/ace/findings.htm. Also www.acestudy.org. Both accessed January 25, 2014.

- Lang PJ, McTeague LM, Bradley MM. Pathological anxiety and function/dysfunction in the brain’s fear/defense circuitry. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2014;32(1):63-77.

- McTeague LM, Lang PJ. The anxiety spectrum and the reflex physiology of defense: from circumscribed fear to broad distress. Depress Anxiety. 2012;29(4):264-281.

- Amen D. Amen Clinics Web site. http://www.amenclinics.com/. Accessed January 20, 2013.

- Perry BD, Pollard RA, Blakeley TL, et al. Childhood Trauma, the Neurobiology of Adaptation, and “Use-dependent” Development of the Brain: How “States” Become “Traits.” Infant Mental Health Journal. Winter 1995;16(4). David Baldwin’s Trauma Information Pages Web site. http://www.trauma-pages.com/a/perry96.php. Accessed January 20, 2014.

- Kosten TR, Mason JW, Giller EL, et al. Sustained urinary norepinephrine and epinephrine elevation in post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1987;12(1):13-20.

- Yehuda R, Southwick SM, Ostroff RB, et al. Neuroendocrine aspects of suicidal behavior. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 1988;17(1):83-102.

- Van der Kolk BA, Greenberg MS, Orr SP, Pitman RK. Endogenous opioids, stress induced analgesia, and posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1989;25(3):417-421.

- Pitman RK, van der Kolk BA, Orr SP, Greenberg MS. Naloxone-reversible analgesic response to combat-related stimuli in posttraumatic stress disorder. A pilot study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990;47(6):541-544.

- National Suicide Prevention Lifeline. http://www.suicidepreventionlifeline.org/. Accessed January 28, 2014.

- Online Assessment Measures (DSM5). American Psychiatric Association Web site. http://www.psych.org/practice/dsm/dsm5/online-assessment-measures. Accessed January 28, 2014.

- Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Web site. http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/post-traumatic-stress-disorder-ptsd/index.shtml. Accessed January 25, 2014.

- Genthner GC, Friedman HL, Studley CF. Improvement in Depression Following Reduction of Upper Cervical Vertebral Subluxation Using Orthospinology Technique. J Vertebral Subluxation Res. November 7, 2005:1-4. http://www.studleychiropractic.com/studies/Depression_Draft1.pdf. Accessed January 28, 2014.

- Elster L. Treatment of bipolar, seizure, and sleep disorders and migraine headaches utilizing a chiropractic technique. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2004;27(3):E5.