CHRIS D. MELETIS, ND

The philosophy of Hippocrates has been shown over the past 2400 years to not only have merit but also notable scientific veracity. Hippocrates advocated a natural approach to the treatment of diseases and emphasized the need for harmony between the individual and social and natural environments.1 His approach is especially relevant to mental disorders such as depression and anxiety. The Hippocratic philosophy centered around the belief that a healthy mind in a healthy body was the cornerstone of good health.1 Hippocrates emphasized that if the body and mind weren’t in harmony, an imbalance occurred that led to disease.1 In keeping with this body-mind philosophy, he encouraged the use of music and drama as a tool for helping patients with mental disorders.1 Hippocrates also advocated physical activity as a critical component of physical and mental health.1 Furthermore, he promoted eating a nutritious diet to enhance performance of athletes in the Olympic Games.1

In treating patients with mental health problems such as depression, anxiety, and insomnia, the modern clinician can replicate this Hippocratic philosophy. Scientists have now identified aspects of these disorders that back up Hippocrates’ philosophy that the health of the mind is tied to the health of the body. For example, we now know that the gut is essentially a “second brain” that can influence our mood. This article will address the connection between the mind and body with respect to depression, anxiety, and insomnia.

The Role of Neuroinflammation

Individuals with major depressive disorder often have elevated levels of inflammatory biomarkers, such as C-reactive protein (CRP), and proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β and IL-6.2 CRP and these cytokines can directly influence mood and emotion.3

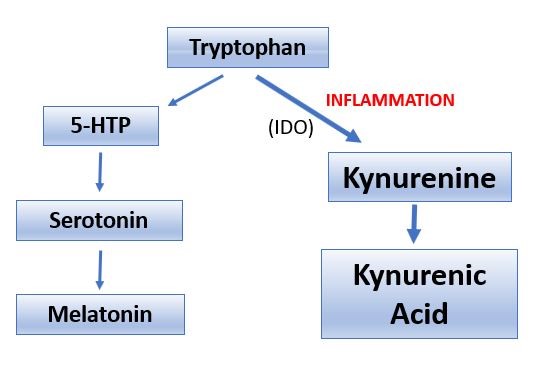

Furthermore, inflammation can indirectly impact mood by influencing tryptophan metabolism. The body can convert the amino acid tryptophan into the feel-good neurotransmitter serotonin and the sleep-inducing-hormone melatonin, or it can convert tryptophan to kynurenine.4 Chronic low-grade inflammation, such as can happen in patients with major depressive disorder (MDD),5 can activate the tryptophan-degrading enzyme, indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), leading to decreased tryptophan levels and upregulation of the kynurenine-pathway (Figure 1).6

Figure 1

When tryptophan is metabolized through the kynurenine pathway, the body has less access to serotonin and melatonin, which are both essential for mood and sleep. Furthermore, the kynurenine pathway generates potentially neurotoxic metabolites, such as such as 3-hydroxykynurenine and quinolinic acid.5,7

The Link Between Sleep & Depression

Insomnia is a risk factor for depression.8,9 It is thought that insomnia-exacerbated inflammation may be the mechanism of action by which chronic sleep loss can lead to depression.10-13 Conversely, depression can also lead to sleep loss, creating a vicious circle.

Inflammation-induced alterations of kynurenine metabolism may explain the association between insomnia and depression. In a study of 68 currently depressed, 26 previously depressed, and 66 never-depressed subjects, only in the currently depressed group was sleep disturbance associated with alterations in kynurenine metabolites.7 Likewise, CRP levels were high only in the subjects with sleep disturbances who were currently depressed.7

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a common sleep disorder that is linked to depression.14 OSA occurs when a patient temporarily stops breathing while sleeping, resulting in low oxygen levels. We can live without food for weeks and water for days, but we can only live without air for moments. OSA does not only occur in obese patients; I have diagnosed mild, moderate, and severe sleep apnea in people who are thin, young, and with no or few classical symptoms. My philosophy is always “test, don’t guess.” The standard treatment for OSA is for patients to use a continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) machine. Resolving sleep apnea can result in a corresponding decrease in depression. Adults with OSA and coronary artery disease experienced reduced depression scores after 3 months of CPAP treatment, compared to participants not using CPAP.15

The Body’s Second Brain

An abundant array of research supports the existence of a gut-brain axis, which points to a strong connection between a healthy gut and optimal mental health and well-being. The fact that the gut microbiota produce or consume various neurotransmitters, including dopamine, norepinephrine, serotonin, and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), is a strong indicator of the connection between the gut and the brain.16 In fact, 90% to 95% of serotonin is produced in the GI tract, mostly in epithelial enterochromaffin cells.16,17 Unfortunately, if tryptophan is metabolized via the kynurenine pathway, the resulting serotonin depletion may contribute to a number of adverse effects including depression and anxiety.18

Animal research has established a direct association between the gut microbiota and many mental disorders, including chronic stress, anxiety, depression, and abnormal feeding behavior.19-21 This association is driven by molecules synthesized from bacteria, including short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), secondary bile acids, and tryptophan metabolites such as 5-HTP (5-hydroxytryptophan) or serotonin that influence neurotransmitter synthesis in the central nervous system (CNS).22 Chemical signals produced in the gut may travel across the intestinal barrier, reaching the systemic circulation, and ultimately crossing the blood-brain barrier.23

Animal models further support the role the GI tract plays in mood regulation through the influence of neurotransmitter levels. In these models, gut microbiota assisted with the regulation of serotonin levels as well as other neurotransmitters.16 Furthermore, research in germ-free animals (lacking a microbiome) determined that rodents without bacteria had significantly lower levels of norepinephrine in the cecal lumen and in the tissue compared with non-germ-free animals.24 The researchers were able to restore cecal levels of norepinephrine by colonizing the animals with a specific pathogen-free microbiota or a mixture of 46 Clostridia species. It was unclear whether the bacteria produced norepinephrine directly or influenced the animals’ production of it. When levels of the neurotransmitter, norepinephrine, are balanced, the body is better able to cope with stress. Imbalanced norepinephrine levels are associated with anxiety, depression, substance abuse, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).25

Human research also indicates that the gut microbiota can influence levels of GABA,26 the major inhibitory neurotransmitter in the CNS. Evidence points to a link between altered GABAergic neurotransmission and CNS disorders, such as anxiety, depression, pain, and sleep.26,27

In humans, dietary interventions can change the composition and function of the gut microbiome.28 For example, consuming a ketogenic diet was shown to increase GABA levels in the cerebrospinal fluid of children with refractory epilepsy and was associated with an improvement in symptoms.29 In addition, in obese people with metabolic syndrome receiving a fecal transplant from lean donors, GABA was the most altered metabolite and was associated with enhanced insulin metabolism.30 This supports the idea that the gut microbiota can affect neurotransmitters involved in mental health.

How Diet Affects Mood & Mental Health

The saying “you are what you eat” is never more true than in regards to mental health. A Western-style diet including excessive fats and sugar can change the composition of the gut microbiota.31 This type of diet is associated with chronic inflammation and obesity and corresponding mental disorders such as depression.31-33 Research in mice indicates that this becomes a vicious circle, whereby eating a Western-style diet can cause depression and anxiety, but withdrawing from this type of eating pattern also causes anxiety as well as a craving for more sweet foods.34 This leaves patients trapped in a pattern that will only cause them to become more depressed and anxious. Ongoing psychological stress only makes matters worse. This is because it impairs the function of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, which often results in increased intake of food,33 especially unhealthy foods. This in turn leads to high cortisol levels, which contributes to obesity.33

NO’s Role in Relieving Depression & Anxiety

Imbalanced levels of the neurotransmitter, nitric oxide (NO), are associated with anxiety and depression, due to NO’s role as a regulator of neuroinflammation.35 NO is thought to influence the release of other neurotransmitters. In doing so, it is involved in brain cell function, such as plasticity and development, and may also increase blood flow to the brain due to its vasodilating actions.35 Abnormalities in NO signaling correlate with major depressive disorder, and certain polymorphisms in the neuronal nitric oxide synthase gene (NOS1) are linked to MDD.36

Natural Support for Depression, Anxiety, & Insomnia

First and foremost, I recommend a Hippocrates-style approach to my patients by prescribing a diet rich in vegetables to raise dietary nitrate, a precursor of NO. Exercise is also important to boost mood. Ideally, exercise should be practiced outdoors at least some of the time, as research indicates spending time in nature can benefit mental health.37 In addition to those foundational strategies, I recommend the following supplements to my patients who need to support their mental health.

Amino Acids & B Vitamins

Eating a healthy diet is only useful if it’s accompanied by proper absorption of nutrients. This is essential for fueling complex biochemical pathways including the citric acid cycle that is essential for manifesting the genetic potential and biochemical output of neurons to make neurotransmitters. For example, sufficient amino acids such as tyrosine, phenylalanine, and tryptophan are required for the body to produce neurotransmitters. Therefore, an amino acid supplement can be used to fuel neurotransmitter production. Likewise, B vitamins such as B6, B12, and folate are necessary for a sense of well-being.38,39 Therefore, a multivitamin or a B vitamin containing the active and bioavailable form of folate is also foundational.

Beetroot Juice

Beetroot juice supports healthy levels of nitric oxide. Beetroot juice as well as dietary nitrates can help maintain the endothelial lining of blood vessels.40 This supports healthy circulation and, in turn, healthy blood pressure and blood flow to the brain.40 In my clinical practice, I find that people who have depression, anxiety, insomnia, or PTSD often have elevated blood pressure, making beetroot juice useful in this group of patients. Additionally, circulation is vitally important for nutrient delivery to target tissues, and the enhancement in circulation through increasing NO can help deliver critical nutrients to the systemic circulation and the brain.

As noted earlier in this article, imbalanced NO levels are associated with anxiety and depression. Consequently, normalizing NO levels may also benefit mental health. However, before beginning supplementation with beetroot juice, I recommend testing patients to establish their nitric oxide levels. The key is to achieve balanced levels of this important neurotransmitter and signaling molecule.

Curcumin

A number of randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials have indicated that Curcuma longa (curcumin) can relieve depression. This may be due to its role in mitigating neuroinflammation. In one of those studies, 80 patients with diabetic polyneuropathy were given 80 mg of nano-curcumin or a placebo daily for 8 weeks.41 Researchers measured the subjects’ depression, anxiety, and stress levels using the Depression, Anxiety, Stress Scale questionnaire before and after the intervention. The curcumin group experienced a pronounced reduction in the mean depression and anxiety scores compared with placebo group. Curcumin had no significant effect on the stress scores.

In another double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, 65 people with MDD randomly received either curcumin or a placebo together with their usual antidepressant medications for 12 weeks.42 The curcumin dose was progressively increased from 500 to 1500 mg per day. Curcumin was more effective than placebo in improving depression scores, especially in the male study participants.

Another trial, this one a double-blind, crossover study of 30 obese individuals, found that 1 gram/day of curcumin for 30 days reduced anxiety compared to the placebo.43 In this study, curcumin had no effect on depression scores.

It should be noted that curcumin can be poorly absorbed by the body. Therefore, it is best to use a form with enhanced bioavailability.

Hemp Oil

Hemp oil contains cannabidiol (CBD), which can support a restorative night’s sleep as well as reduce depression and anxiety. CBD may reduce REM sleep behavior disorder and excessive sleepiness during the day.44 Furthermore, it was shown that people with insomnia given 160 mg CBD slept more deeply and awakened less during the night compared with the placebo.45 A case report also found that CBD oil reduced anxiety and improved sleep in a child suffering from PTSD.46

At high concentrations, CBD can directly activate the 5-HT1A serotonin receptor, which mediates antidepressant actions.47 CBD has been found in human research to reduce anxiety in individuals with generalized social anxiety disorder.47 In other human studies, CBD at doses of 300-600 mg reduced anxiety in subjects participating in a simulated public speaking test.48,49

L-Theanine

This green-tea-derived botanical promotes relaxation and a state of calm alertness. In a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover trial, researchers gave 200 mg/day L-theanine supplements or a placebo to 30 healthy adults.50 Four weeks of L-theanine administration led to falling asleep faster, staying asleep longer, and reduced use of sleep medication compared to the placebo. Moreover, verbal fluency and executive function scores improved after supplementing with L-theanine. In an open-label study, L-theanine supplements were given to patients with MDD along with their current medication.51 Eight weeks of L-theanine supplementation led to decreased depression and anxiety scores. L-theanine was also associated with improved sleep and cognition, including verbal memory and executive function.

Rhodiola

Rhodiola rosea is an adaptogen that helps the body cope with stress. Doses of 200 mg twice daily have been found to reduce anxiety, stress, anger, confusion, and depression.52 It is also effective in reducing stress-related fatigue.53,54 Rhodiola is a good choice for patients with obstructive sleep apnea, as it was shown in one study to reduce anxiety and depression in this group of patients through a mechanism that involved blocking oxygen free radicals and lipid peroxidation.55

Probiotics

Due to the existence of the gut-brain axis, the inclusion of a probiotic supplement will increase the effectiveness of a depression, anxiety, and insomnia regimen. Supplementing with probiotics has been shown to reduce depression and anxiety.56-59 Probiotics can also be used to normalize the kynurenine pathway. The probiotic bacteria Lactobacillus Plantarum 299v was shown to reduce kynurenine levels and improve cognitive function in patients with MDD.60 Eating a healthy, Mediterranean-style diet can also favorably impact the gut microbiota.61

Conclusion

Science is now validating the mind-body approach Hippocrates used thousands of years ago. The existence of the gut-brain axis, establishing a connection between the mind and GI tract, firmly points to a connection between the health of the gut and the condition of the mind. In fact, neurotransmitters such as serotonin are primarily produced in the gut. Depression and anxiety are influenced by gut health, as well as other factors such as neuroinflammation and imbalanced nitric oxide levels. Diet, exercise, restorative sleep, and supplementation with such botanicals and nutrients as amino acids, active B-vitamins, beetroot juice, curcumin, hemp oil, L-theanine, rhodiola, and probiotics can go a long way in promoting a sense of happiness and well-being.

References:

- Kleisiaris CF, Sfakianakis C, Papathanasiou IV. Health care practices in ancient Greece: The Hippocratic ideal. J Med Ethics Hist Med. 2014;7:6.

- Howren MB, Lamkin DM, Suls J. Associations of depression with C-reactive protein, IL-1, and IL-6: a meta-analysis. Psychosom Med. 2009;71(2):171-186.

- Miller AH, Haroon E, Raison CL, Felger JC. Cytokine targets in the brain: impact on neurotransmitters and neurocircuits. Depress Anxiety. 2013;30(4):297-306.

- Myint AM, Bondy B, Baghai TC, et al. Tryptophan metabolism and immunogenetics in major depression: a role for interferon-γ gene. Brain Behav Immun. 2013;31:128-133.

- Savitz J, Drevets WC, Wurfel BE, et al. Reduction of kynurenic acid to quinolinic acid ratio in both the depressed and remitted phases of major depressive disorder. Brain Behav Immun. 2015;46:55-59.

- Dantzer R, O’Connor JC, Freund GG, Johnson RW, Kelley KW. From inflammation to sickness and depression: when the immune system subjugates the brain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9(1):46-56.

- Cho HJ, Savitz J, Dantzer R, et al. Sleep disturbance and kynurenine metabolism in depression. J Psychosom Res. 2017;99:1-7.

- Cho HJ, Lavretsky H, Olmstead R, et al. Sleep disturbance and depression recurrence in community-dwelling older adults: a prospective study. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(12):1543-1550.

- Baglioni C, Battagliese G, Feige B, et al. Insomnia as a predictor of depression: a meta-analytic evaluation of longitudinal epidemiological studies. J Affect Disord. 2011;135(1-3):10-19.

- Irwin MR, Carrillo C, Olmstead R. Sleep loss activates cellular markers of inflammation: sex differences. Brain Behav Immun. 2010;24(1):54-57.

- Irwin MR, Wang M, Campomayor CO, et al. Sleep deprivation and activation of morning levels of cellular and genomic markers of inflammation. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(16):1756-1762.

- Irwin MR, Witarama T, Caudill M, et al. Sleep loss activates cellular inflammation and signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) family proteins in humans. Brain Behav Immun. 2015;47:86-92.

- Cho HJ, Eisenberger NI, Olmstead R, et al. Preexisting mild sleep disturbance as a vulnerability factor for inflammation-induced depressed mood: a human experimental study. Transl Psychiatry. 2016;6(3):e750.

- Hodges E, Marcus CL, Kim JY, et al. Depressive symptomatology in school-aged children with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: incidence, demographic factors, and changes following a randomized controlled trial of adenotonsillectomy. Sleep. 2018;41(12):zsy180.

- Balcan B, Thunström E, Strollo PJ Jr, Peker Y. Continuous Positive Airway Pressure Treatment and Depression in Adults with Coronary Artery Disease and Nonsleepy Obstructive Sleep Apnea. A Secondary Analysis of the RICCADSA Trial. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2019;16(1):62-70.

- Strandwitz P. Neurotransmitter modulation by the gut microbiota. Brain Res. 2018;1693(Pt B):128-133.

- Gershon MD, Tack J. The serotonin signaling system: from basic understanding to drug development for functional GI disorders. Gastroenterology. 2007;132(1):397-414.

- Kennedy PJ, Cryan JF, Dinan TG, Clarke G. Kynurenine pathway metabolism and the microbiota-gut-brain axis. Neuropharmacology. 2017;112(Pt B):399-412.

- Sandhu KV, Sherwin E, Schellekens H, et al. Feeding the microbiota-gut-brain axis: diet, microbiome, and neuropsychiatry. Transl Res. 2017;179:223-244.

- Martin CR, Osadchiy V, Kalani A, Mayer EA. The Brain-Gut-Microbiome Axis. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;6(2):133-148.

- Winter G, Hart RA, Charlesworth RPG, Sharpley CF. Gut microbiome and depression: what we know and what we need to know. Rev Neurosci. 2018;29(6):629-643.

- O’Mahony SM, Clarke G, Borre YE, et al. Serotonin, tryptophan metabolism and the brain-gut-microbiome axis. Behav Brain Res. 2015;277:32-48.

- Haghikia A, Jörg S, Duscha A, et al. Dietary Fatty Acids Directly Impact Central Nervous System Autoimmunity via the Small Intestine. Immunity. 2015;43(4):817-829.

- Asano Y, Hiramoto T, Nishino R, et al. Critical role of gut microbiota in the production of biologically active, free catecholamines in the gut lumen of mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2012;303(11):G1288-1295.

- Montoya A, Bruins R, Katzman MA, Blier P. The noradrenergic paradox: implications in the management of depression and anxiety. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2016;12:541-557.

- Kalueff AV, Nutt DJ. Role of GABA in anxiety and depression. Depress Anxiety. 2007;24(7):495-517.

- Wong CG, Bottiglieri T, Snead OC 3rd. GABA, gamma-hydroxybutyric acid, and neurological disease. Ann Neurol. 2003;54 Suppl 6:S3-S12.

- David LA, Maurice CF, Carmody RN, et al. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature. 2014;505(7484):559-563.

- Dahlin M, Elfving A, Ungerstedt U, Amark P. The ketogenic diet influences the levels of excitatory and inhibitory amino acids in the CSF in children with refractory epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 2005;64(3):115-125.

- Kootte RS, Levin E, Salojärvi J, et al. Improvement of Insulin Sensitivity after Lean Donor Feces in Metabolic Syndrome Is Driven by Baseline Intestinal Microbiota Composition. Cell Metab. 2017;26(4):611-619.e616.

- Martinez KB, Leone V, Chang EB. Western diets, gut dysbiosis, and metabolic diseases: Are they linked? Gut Microbes. 2017;8(2):130-142.

- Zinöcker MK, Lindseth IA. The Western Diet-Microbiome-Host Interaction and Its Role in Metabolic Disease. Nutrients. 2018;10(3):365.

- López-Taboada I, González-Pardo H, Conejo NM. Western Diet: Implications for Brain Function and Behavior. Front Psychol. 2020;11:564413.

- Sharma S, Fernandes MF, Fulton S. Adaptations in brain reward circuitry underlie palatable food cravings and anxiety induced by high-fat diet withdrawal. Int J Obes (Lond). 2013;37(9):1183-1191.

- McLeod TM, López-Figueroa AL, López-Figueroa MO. Nitric oxide, stress, and depression. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2001;35(1):24-41.

- Kudlow P, Cha DS, Carvalho AF, McIntyre RS. Nitric Oxide and Major Depressive Disorder: Pathophysiology and Treatment Implications. Curr Mol Med. 2016;16(2):206-215.

- Vujcic M, Tomicevic-Dubljevic J, Grbic M, et al. Nature based solution for improving mental health and well-being in urban areas. Environ Res. 2017;158:385-392.

- Tsujita N, Akamatsu Y, Nishida MM, et al. Effect of Tryptophan, Vitamin B(6), and Nicotinamide-Containing Supplement Loading between Meals on Mood and Autonomic Nervous System Activity in Young Adults with Subclinical Depression: A Randomized, Double-Blind, and Placebo-Controlled Study. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo). 2019;65(6):507-514.

- Zajecka JM, Fava M, Shelton RC, et al. Long-term efficacy, safety, and tolerability of L-methylfolate calcium 15 mg as adjunctive therapy with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: a 12-month, open-label study following a placebo-controlled acute study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(5):654-660.

- Jones T, Dunn EL, Macdonald JH, et al. The Effects of Beetroot Juice on Blood Pressure, Microvascular Function and Large-Vessel Endothelial Function: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Pilot Study in Healthy Older Adults. Nutrients. 2019;11(8):1792.

- Asadi S, Gholami MS, Siassi F, et al. Beneficial effects of nano-curcumin supplement on depression and anxiety in diabetic patients with peripheral neuropathy: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Phytother Res. 2020;34(4):896-903.

- Kanchanatawan B, Tangwongchai S, Sughondhabhirom A, et al. Add-on Treatment with Curcumin Has Antidepressive Effects in Thai Patients with Major Depression: Results of a Randomized Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Study. Neurotox Res. 2018;33(3):621-633.

- Esmaily H, Sahebkar A, Iranshahi M, et al. An investigation of the effects of curcumin on anxiety and depression in obese individuals: A randomized controlled trial. Chin J Integr Med. 2015;21(5):332-338.

- Babson KA, Sottile J, Morabito D. Cannabis, Cannabinoids, and Sleep: a Review of the Literature. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2017;19(4):23.

- Carlini EA, Cunha JM. Hypnotic and antiepileptic effects of cannabidiol. J Clin Pharmacol. 1981;21(S1):417s-427s.

- Shannon S, Opila-Lehman J. Effectiveness of Cannabidiol Oil for Pediatric Anxiety and Insomnia as Part of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Case Report. Perm J. 2016;20(4):16-005.

- Crippa JA, Derenusson GN, Ferrari TB, et al. Neural basis of anxiolytic effects of cannabidiol (CBD) in generalized social anxiety disorder: a preliminary report. J Psychopharmacol. 2011;25(1):121-130.

- Linares IM, Zuardi AW, Pereira LC, et al. Cannabidiol presents an inverted U-shaped dose-response curve in a simulated public speaking test. Braz J Psychiatry. 2019;41(1):9-14.

- Bergamaschi MM, Queiroz RH, Chagas MH, et al. Cannabidiol reduces the anxiety induced by simulated public speaking in treatment-naïve social phobia patients. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36(6):1219-1226.

- Hidese S, Ogawa S, Ota M, et al. Effects of L-Theanine Administration on Stress-Related Symptoms and Cognitive Functions in Healthy Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients. 2019;11(10):2362.

- Hidese S, Ota M, Wakabayashi C, et al. Effects of chronic l-theanine administration in patients with major depressive disorder: an open-label study. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2017;29(2):72-79.

- Cropley M, Banks AP, Boyle J. The Effects of Rhodiola rosea L. Extract on Anxiety, Stress, Cognition and Other Mood Symptoms. Phytother Res. 2015;29(12):1934-1939.

- Ross SM. Rhodiola rosea (SHR-5), Part I: a proprietary root extract of Rhodiola rosea is found to be effective in the treatment of stress-related fatigue. Holist Nurs Pract. 2014;28(2):149-154.

- Darbinyan V, Kteyan A, Panossian A, et al. Rhodiola rosea in stress induced fatigue–a double blind cross-over study of a standardized extract SHR-5 with a repeated low-dose regimen on the mental performance of healthy physicians during night duty. Phytomedicine. 2000;7(5):365-371.

- Yu HL, Zhang PP, Zhang C, et al. Effects of rhodiola rosea on oxidative stress and negative emotional states in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Lin Chung Er Bi Yan Hou Tou Jing Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2019;33(10):954-957. [Article in Chinese]

- Moludi J, Alizadeh M, Mohammadzad MHS, Davari M. The Effect of Probiotic Supplementation on Depressive Symptoms and Quality of Life in Patients After Myocardial Infarction: Results of a Preliminary Double-Blind Clinical Trial. Psychosom Med. 2019;81(9):770-777.

- Chahwan B, Kwan S, Isik A, et al. Gut feelings: A randomised, triple-blind, placebo-controlled trial of probiotics for depressive symptoms. J Affect Disord. 2019;253:317-326.

- Tran N, Zhebrak M, Yacoub C, et al. The gut-brain relationship: Investigating the effect of multispecies probiotics on anxiety in a randomized placebo-controlled trial of healthy young adults. J Affect Disord. 2019;252:271-277.

- Chong HX, Yusoff NAA, Hor YY, et al. Lactobacillus plantarum DR7 alleviates stress and anxiety in adults: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Benef Microbes. 2019;10(4):355-373.

- Rudzki L, Ostrowska L, Pawlak D, et al. Probiotic Lactobacillus Plantarum 299v decreases kynurenine concentration and improves cognitive functions in patients with major depression: A double-blind, randomized, placebo controlled study. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2019;100:213-222.

- Haro C, García-Carpintero S, Rangel-Zúñiga OA, et al. Consumption of Two Healthy Dietary Patterns Restored Microbiota Dysbiosis in Obese Patients with Metabolic Dysfunction. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2017;61(12).

Chris D. Meletis, ND is an educator, international author, and lecturer. He has authored 18 books and more than 200 scientific articles in prominent journals and magazines. Dr Meletis served as Dean of Naturopathic Medicine and CMO for 7 years at NUNM. He was recently awarded the NUNM Hall of Fame award by OANP, as well as the 2003 Physician of the Year by the AANP. Dr Meletis spearheaded the creation of 16 free natural medicine healthcare clinics in Portland, OR. Dr Meletis serves as an educational consultant for Fairhaven Health, Berkeley Life, TruGen3, US BioTek, and TruNiagen. He has practiced in Beaverton, OR, since 1992.