David Schleich, PhD

Part One

Numerous teachers and scholars in the medical education field believe that their biggest job is to help our interns learn how to integrate communication and clinical reasoning (Mead and Bower). The elements of our curricula, they believe, have to establish by example and experience the relation between these two skills (Evans et al.). Given the enormous potential of naturopathic medicine in the current healthcare landscape, these same teachers know the sacred trust they are accorded to design and deliver curricula that lead students to value the connection among the psychosocial, nature cure and biomedical aspects of patient care. In that sense, our curricula must provide for healthy solicitation of patient concerns and very skilled exploration of the psychosocial issues presenting along with biomedical ones. Our ND graduates have to be very confident about learning how to understand and prioritize problems; how to generate confidence, intuition and skill in crisp clinical reasoning (Kempainen et al.); how to become adept at forging therapeutic alliances and how to develop excellent habits and constant vigilance about avoiding medical error and harm (Windish et al.). These are formidable goals for naturopathic medical education. To achieve these goals, the naturopathic medical education community has many opportunities these days and many burdens in its mission to design and deliver the best education and training possible to build the profession.

The naturopathic medical education community shares some of these burdens with other professional preparation programs in the higher education community. Our funding resources, administrative habits and accountabilities are affected by rising operating costs, the ongoing urgency of relevant well-designed curricula, the special challenge of recruiting and retaining full-time teachers and researchers with strong clinical backgrounds and a passion for building the profession and the perennial challenge of aligning and maintaining our plant and property facilities with our delivery needs. Our experience actually is made even more interesting because we take seriously the notion that being a physician also means being a teacher. So, we are not only preparing clinicians with theoretical knowledge, practical knowledge, technical skill and professional passion for the medicine grounded in principles and a clear philosophy, but we are also getting them ready to be teachers and healers all at the same time. Add into the mix our need to train our own teachers to be teachers, and the mission gets even more complex (Kurtz and Silverman).

Most of us have heard about the etymology of the terms doctor and teacher from classical Latin: doctor is from docēre/doctor, meaning “religious teacher, adviser, scholar,” and teacher is the agent noun from docēre, meaning “to show, teach, cause to know.” For a long time, we have been proud of the relational nature of our approach to healing, emphasizing that we teach our patients skills and knowledge for lifelong wellness and self-responsibility, along with delivering our clinical pearls. That we are teaching physicians to be healers and teachers too, and that we are teachers ourselves, makes our community very special indeed.

From that perspective, accompanying the inevitable complexity of presenting and producing curriculum content that converts our students into primary care physicians is the obligation to build into that long apprenticeship of acquiring the right knowledge, attitudes, behaviors and skills, as well as a capacity for teaching, mentoring and communication (Rogers et al.). Ultimately, the stability, growth and vitality propelling forward the roots of the profession are entrusted to our teachers, who are in our unique world also teachers of teachers. Our profession’s beliefs, values and deontology, as well as the essential clinical and technical skills our graduates must bring with them into clinical practice, simply have to emerge in sufficient quantity, quality and transferability from their educational experience. That is indeed a sacred trust for our teachers.

Our teachers have the critical mandate of facilitating the mastering of key knowledge,  attitudes and behaviors essential to success in a healthcare landscape that is unforgiving in its economic and political realities. They can make or break the profession’s identity, its momentum and its power. All that responsibility, however, leads to a certain tension between the field and the academy. John Orlando on this point reminds us of Etienne Wenge’s admonition that “entering a profession requires learning the communities of practice of that profession—putting on the dressing of the practitioner in order to see the world as the practitioner sees it” (Orlando). There are those in full-time practice who worry that those not in full-time practice can over time lose touch with what is most urgent on the front line of primary care. And compounding the challenge, there is the inevitable challenge of incorporating the traditions and roots of naturopathic medicine with what is new.

attitudes and behaviors essential to success in a healthcare landscape that is unforgiving in its economic and political realities. They can make or break the profession’s identity, its momentum and its power. All that responsibility, however, leads to a certain tension between the field and the academy. John Orlando on this point reminds us of Etienne Wenge’s admonition that “entering a profession requires learning the communities of practice of that profession—putting on the dressing of the practitioner in order to see the world as the practitioner sees it” (Orlando). There are those in full-time practice who worry that those not in full-time practice can over time lose touch with what is most urgent on the front line of primary care. And compounding the challenge, there is the inevitable challenge of incorporating the traditions and roots of naturopathic medicine with what is new.

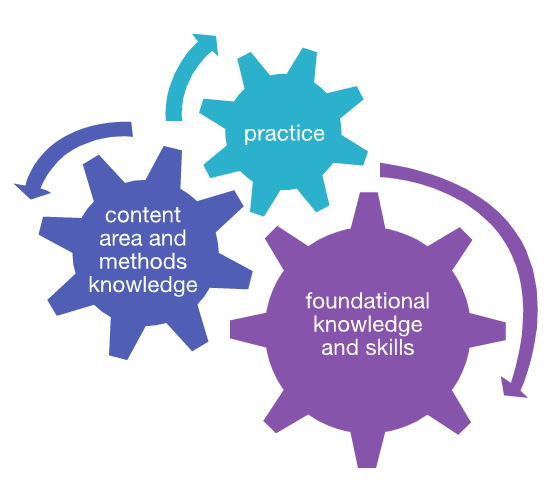

Despite that remarkable responsibility, just as is the case in most of the higher education arena, including professional preparation, there are no formal programs to prepare and sustain our teachers. There are no consistent teacher preparation programs, no funded sabbaticals in base budgets and little by way of required and sustained continuing education in the area of teacher training. Even the Council on Naturopathic Medical Education and regional accreditation standards are silent on this fundamental aspect of naturopathic medical education, alluding to entry-level qualifications but not to ongoing teacher education. The same can be said of course about teachers in the allopathic field. In fact, the concern is generalizable across the spectrum of higher education programming (Association of American Medical Colleges). There is an exception, and that is teacher education in the elementary and secondary tiers. Such programs usually begin with foundational knowledge and skills, which in turn drives two other factors in professional preparation: (1) content area and methods knowledge and (2) practice.

In our case, there are many physicians in the field who would insist that foundational knowledge should be grounded in naturopathic philosophy and history. Courses that familiarize our students with those principles and ideas are usually front-loaded in our seven programs. At the same time, however, there is less time in an already crowded program for a more intensive study of the history of medicine or of the sociology of naturopathic medicine, frameworks for understanding professional formation in our time. The philosophy curricula across our schools have many least common denominators. This dimension of professional preparation is a strong priority among our current students, as well as among many physicians who have been out in practice for some time.

Comparison of Philosophy Curricula by Abigail Ellsworth, Education Vice President, Naturopathic Medical Student Association, December 2010

| Class | Description |

| National University of Health Sciences, Lombard, IL | |

| FH510N: Fundamentals of Natural Medicine and Historical Perspectives | Students are introduced to the historical perspective of the common principles and origins on which natural medicine concepts were founded and developed with emphasis on naturopathic and chiropractic medicine. The concepts of the science of manual therapy and its effect on tissue physiology, neurological processes, and psychophysiological aspects are introduced. The whole health concept of patient care will be introduced in this course. This course will also introduce concepts of personal and collective duties of professionalism, ethics and self-reflection that must be developed by future physicians. |

| NT5110N: Foundations of Naturopathic Medicine I | This course forms the basis of the clinical theory stream of courses in the ND program, which serves as a framework for practice. The course begins with an overview and the vision and ultimate goals of the ND program. The naturopathic principles are discussed at length. Major concepts such as health, holism, and vitalism are analyzed by the class. Ecology and environmental health as a basis for individual health, and the broader implications of the Gaia theory are explored. Spirituality and its importance to life and healing, and the need for the physicians to be whole themselves, form the concluding portion of the course. |

| NT5211N: Foundations of Naturopathic Medicine II | This course examines the historical and cultural roots of naturopathic medicine. The history of Western medicine and the roots of naturopathic medicine in the context of 19th century nature cure are examined. The role and experience of women in medicine is discussed. A portion of the course will explore the evolution and relevance to naturopathic medicine of various world medical systems (East Asian, South Asian, African, etc.). As a prelude to future clinical theory courses, and the development of therapeutic skills, the course will conclude with some discussion of clinical theory, such as the therapeutic order. |

| University of Bridgeport College of Naturopathic Medicine, Bridgeport, CT | |

| NPP511: History of Naturopathic Medicine | This course will examine the historical, socioeconomic, and political foundations of Naturopathic Medicine and its eclectic blend of healing arts and fundamental roots; Botanical Medicine, Nature Cure, Physical Medicine, Hydrotherapy, Homeopathy, Energy Medicine, and Ancient Healing systems from around the globe. |

| NPP512: Philosophy of Naturopathic Medicine 1 | This course will explore the philosophical foundations of naturopathic medicine, which form the basis for therapeutic intervention. Vitalistic medicine in the United States of America as an influence on the creation of the naturopathic profession will be discussed. The overall emphasis of the course will be on the philosophical principles that define the empirical “natural laws” which describe the phenomenon of healing. The relationship of naturopathic principles to medical science is included. |

| NPP522: Philosophy of Naturopathic Medicine II | Nature acts powerfully through healing mechanisms in the body and mind to maintain and restore health. Students will receive a more in-depth utilization of naturopathic methods and medicinal substances, which work in harmony with the human system, thus facilitating long-lasting health and recovery. In addition to employing various natural medicines, students will gain an important perspective of the vital force and its role in the healing process, when used in conjunction with naturopathic principles. Prerequisite: NPP512. |

| Canadian College of Naturopathic Medicine, Toronto, ON | |

| FNM201: Foundations of Naturopathic Medicine | Students are engaged in interpreting, debating and assessing the principles and philosophical underpinnings that define naturopathic medicine. Students discover how these principles and theories are applied in practice through panel discussions with naturopathic doctors with diverse practice styles and clinical approaches. |

| NPH101: Naturopathic History, Philosophy and Principles | This course engages students in an exploration of the basic underlying principles of naturopathic medicine. These principles are understood through philosophical discussion of concepts such as holism, vitalism and health. The historical evolution of medicine and the naturopathic profession are examined. Students will know and understand the Naturopathic Doctor’s Oath, and identify what the values and principles in the oath mean to them. |

| NPH102: Art and Practice of Naturopathic Medicine | This course explores the many facets of naturopathic medicine, including its major modalities and the manner by which they are incorporated into a unified approach to healing. The major qualities and skills required for naturopathic medicine are addressed in the context of the program, as well as the ongoing experience necessary to cultivate those skills and qualities. The principles discussed in NPH101 are applied in a small group setting. (Prerequisite: NPH101) |

| Bastyr University, Kenmore, WA | |

| NP5113: Naturopathic Medicine in Historical Context | This course traces the roots of naturopathic medicine and the development of its modalities and philosophy from 4,000 BC to the present day. Lab cohorts are introduced to the principles and practices of naturopathic medicine and discuss them in a historical context to gain an understanding of the philosophical, political and therapeutic constructs that shaped our current profession. |

| NM5114: Fundamentals of Naturopathic Clinical Theory | Naturopathic principles of practice, concepts of health and disease, environment, hygiene, nature cure, natural therapeutics, prevention and wellness are discussed with an emphasis on the vitalistic context of science-based naturopathic medicine. Lab cohorts explore the naturopathic principles, therapeutic order and determinants of health more deeply and begin to apply them to cases. |

| NM5115: Naturopathic Medicine in Global Context | This course explores the current practice of natural medicine across the globe. Students survey traditional healing methods as well as institutional practices of natural therapeutics. Drawing on the historical and philosophical information given the previous two quarters, students gain an understanding of the current political, social and cultural context of natural medicine in each region. The lab cohorts explore the different philosophical and clinical practices of each region and discuss/experience how these complement current naturopathic philosophy and practice. |

| National College of Natural Medicine, Portland, OR | |

| NPH410: Naturopathic Medical History, Philosophy and Therapeutics | This lecture and discussion course introduces the philosophical basis of naturopathic medicine and the role of the naturopathic physician in today’s world. Students will examine the roots of naturopathic medicine and the historical development of naturopathic philosophy. Emphasis is placed on the six guiding principles of naturopathic care: the healing power of nature, treat the whole person, first do no harm, identify and treat the cause, prevention and the doctor as the teacher. |

| NPH411: Naturopathic Retreat | This weekend retreat provides an opportunity to discuss and experience nature-cure and related therapies in a natural setting. |

| NPH511: Naturopathic Medical Philosophy and Therapeutics | Students examine the development of naturopathic philosophy, discuss the principles of natural healing, and examine naturopathic therapeutic systems and their relationships to the underlying philosophy. |

| NPH531: Naturopathic Medical Philosophy Tutorial | This case-based module is designed to promote integration of naturopathic principles and philosophy in a small group setting. The goal of this module is to support solutions to clinical problems; and encourage diagnostic strategies and selection of therapeutics informed by naturopathic medical philosophy. |

| Southwest College of Naturopathic Medicine & Health Sciences, Tempe, AZ | |

| NTMD 605: Philosophy and History of Naturopathic Medicine | Students are introduced to the historical context of naturopathic medicine as it relates to the development and evolution of practice. Students review ancient, medieval, cultural and historical trends in medicine as a whole and in naturopathic medicine. This class will also explore the inclusion of socioeconomic, political, legal, ethical, and patient management perspective in understanding the issues faced by naturopathic physicians today. The naturopathic philosophical framework is examined along with its therapeutics and modalities and how they apply to naturopathic principles. Emphasis is placed on the current professional, legal, and economic status of naturopathic medicine and strategies with regard to its advancement within the American health care system. |

| NTMD880: Analysis and Integration of Naturopathic Philosophy and Practice | In this course students have the opportunity at the end of their program, to re-examine the philosophy and principles of naturopathic medicine for use in their own practices. Also included is discussion that outlines actions students may take to advance the profession as they begin their own practices. |

| Boucher Institute of Naturopathic Medicine, New Westminster, BC, Canada | |

| NCAS501-503: Naturopathic Clinical Arts and Sciences I-III | History and Philosophy of Naturopathic Medicine presents the history of naturopathic medicine within the context of the overall history of the healing arts and their various manifestations at different times and in different cultures. This course is included in Naturopathic Clinical Arts and Sciences I. Several models of health and disease are explored, and the unique philosophy of naturopathic medicine is introduced and traced from its historical origins through modern science-based theory and practice. The vis medicatrix naturae is discussed in depth as the basis for naturopathic concepts of health and disease and principles of practice, and as the unifying principle that distinguishes naturopathic practice from other forms of medicine and underlies naturopathic therapeutic modalities. The fundamental concepts and key issues in naturopathic philosophy are examined and their significance discussed in terms of the internal coherence and consistency of the naturopathic body of knowledge.

The principles of naturopathic clinical practice and the various therapies used in naturopathic medicine are introduced and discussed. The characteristic features of constructive organization, interconnectedness, and interdependence in the natural world, in biological organisms and communities, and in individual persons are identified. The student is thus prepared to apply the concepts of organization and wholeness to the naturopathic study of health, disease and healing, and to the healing methods and agents employed in naturopathic medicine. This survey of naturopathic philosophy supplies an essential perspective for the curriculum as a whole. These principles are reinforced throughout the educational experience, including the clinical experience. |

| NCAS604-606: Naturopathic Clinical Arts and Sciences IV-VI | |

| NCAS707-709: Naturopathic Clinical Arts and Sciences VII-IX | |

| NCAS810-812: Naturopathic Clinical Arts and Sciences X-XII | |

There are others, however, who believe that the basic medical sciences are the most important foundation of professional preparation. In this connection, the concept in curriculum of “content area and methods knowledge” is part of what Donald Schon references in The Reflective Practitioner. In his model, professional preparation is usually designed in three streams: basic sciences, applied sciences and a practicum or “methods” element of training. The methods dimension manifests in clinical internships, field placements, preceptoring and postgraduate medical education in the form of residencies (Schmidt, Kurz et al., Kurz and Silverman).

Our long-service teachers have experienced an increased load of expectation within these three sectors of education and training for our physicians. They are challenged to know in advance what kinds of knowledge and skills our ND students will need when they enter professional life. The field of natural medicine is transforming all the time (Kern et al.). Meanwhile, the allopathic profession has not hesitated to cherry-pick our approach and some of our modalities, and we have some lay imitators as well. Thus, it becomes harder to know what kinds of knowledge and skill teachers should prioritize, especially in an educational environment where the balancing of the roots of naturopathic medicine with the pressures to adopt some aspects of so-called green allopathy are growing.

Over the years, another default in our curricula has been to include adjunct faculty who are in practice in the field but who also wish to teach part-time. These teachers can influence choices in content and skills acquisition. Some scholars call this transversal or horizontal skills acquisition, whereby systematic review of curricula is not possible in the dense time frames and restricted budgets of our colleges. Generally, there is not a systemwide strategy to support ways for our teachers to become proficient in keeping up with sometimes rapid developments of knowledge and clinical skills. Essentially we ask, often indirectly, that our teachers themselves be very good at “learning to learn” and at selecting and ordering from the continuum of their professional experience, practice and scholarship the most urgently needed intellectual, clinical, professional and social competencies our graduates need to enter the marketplace successfully.

This expectation can inadvertently bump into our comfort zone around being sure that in our classrooms and teaching clinics our teachers know what to do and are supported by the right tools to do the job. This dynamic begs two questions: (1) What do we know about how our traditional ways of designing, evaluating and delivering curricula occur? (2) Can continue to rely on these design and approval mechanisms for those curricula? Our ways of working in the classroom and in the teaching clinic are, therefore, impacted not only by a generation of students as comfortable with Twitter and Wikipedia as we once were with card catalogs and the “sage on the stage” who showed the way, but also by our collective efforts to recruit, train and support our teachers in those places where their career paths intersect in the colleges.

In the model by Donald Schon, the third key element of curriculum involves the practicum element. Our students have to be supervised and supported in some way to apply what they have learned and to build confidence about starting out as physicians in a very competitive environment. Our clinical opportunities are limited to outpatient experiences in our teaching clinics and in some cases to community clinics, where the presenting conditions are often more. There are concerns that the conventional organization of the practicum element of our curricula is somewhat artificial and unrepresentative of how physicians actually experience their work. Practice problems frequently (perhaps usually) concern foundational issues, curriculum and practical knowledge simultaneously, and separating them during medical education may not be helpful. The major goal is to teach our ND interns how to integrate communication and clinical reasoning. The elements of our curricula have to establish by example and experience the relation between these two skills. To strategize the role of naturopathic medicine in the current healthcare arena, the curricula will need to connect the psychosocial, nature cure and biomedical aspects of patient care. Our curricula must provide for healthy solicitation of patient concerns and for very skilled exploration of the psychosocial issues presenting alongside biomedical ones. Our ND graduates have to be very confident about appropriate prioritization of problems, crisp clinical reasoning, adept therapeutic alliances and constant vigilance about avoiding medical error and harm (Kempainen et al.).

Next month, we shall examine a teacher training program model for our naturopathic programs. The model could aid in this important task of preparing the teachers of our healers, who are also teachers.

David J. Schleich, PhD, is president and CEO of NCNM, former president of Truestar Health, and former CEO and president of CCNM, where he served from 1996 to 2003. Previous posts have included appointments as vice president academic of Niagara College, and administrative and teaching positions at St. Lawrence College, Swinburne University (Australia) and the University of Alberta. His academic credentials have been earned from the University of Western Ontario (BA), the University of Alberta (MA), Queen’s University (BEd), and the University of Toronto (PhD).

David J. Schleich, PhD, is president and CEO of NCNM, former president of Truestar Health, and former CEO and president of CCNM, where he served from 1996 to 2003. Previous posts have included appointments as vice president academic of Niagara College, and administrative and teaching positions at St. Lawrence College, Swinburne University (Australia) and the University of Alberta. His academic credentials have been earned from the University of Western Ontario (BA), the University of Alberta (MA), Queen’s University (BEd), and the University of Toronto (PhD).

References

Association of American Medical Colleges. “Report I: Learning Objectives for Medical Student Education: Guidelines for Medical Schools: Medical School Objectives Project.” January 1998. https://services.aamc.org/publications/showfile.cfm?file=version87.pdf&prd_id=198&prv_id=239&pdf_id=87.

Evans, R.J., R.O. Stanley, R. Mestrovic, and L. Rose. “Effects of Communication Skills Training on Students’ Diagnostic Efficiency.” Medical Education. 25, 1992: 517-26.

Kempainen, R.R., M.B. Migeon, and F.M. Wolf. “Understanding Our Mistakes: A Primer on Errors in Clinical Reasoning.” Medical Teacher. 25(2), 2003: 177-81.

Kern, D.E., P.A. Thomas, D.M. Howard, and E.B. Bass. Curriculum Development for Medical Education: A Six-Step Approach. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998.

Kurtz, S. and J. Silverman. “The Calgary-Cambridge Referenced Observation Guides: An Aid to Defining the Curriculum and Organizing the Teaching in Communication Training Programs.” Medical Education. 30, 1996: 83-9.

Kurtz, S.M, J.D. Silverman, and J. Draper. Teaching and Learning Communication Skills in Medicine. Oxford, England: Radcliffe Medical Press, 1998.

Mead, N. and P. Bower. “Patient-Centred Consultations and Outcomes in Primary Care: A Review of the Literature.” Patient Education and Counseling. 48(1), 2002: 51-61.

Orlando, J. “Tapping Into the Power of Open Education to Improve Teaching and Learning.” Faculty Focus. 2011. http://www.facultyfocus.com.

Rogers, J.C., D.E. Swee, and J.A. Ullian. “Teaching Medical Decision Making and Students’ Clinical Problem Solving Skills.” Medical Teacher. 13, 1991: 157-63.

Schmidt, H. “Integrating the Teaching of Basic Sciences, Clinical Sciences, and Biopsychosocial Issues.” Academic Medicine. 73(suppl.), 1998: S24-31.

Schon, D. The Reflective Practitioner. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1987.

Windish, D.M., P.M. Paulman, A.H. Goroll, and E.B. Bass. “Do Clerkship Directors Think Medical Students Are Prepared for the Clerkship Years?” Academic Medicine. 79(1), 2004: 56-61.