Into the Forest? Making Space for Elders’ Wisdom

Naturopathic Perspective

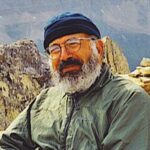

Jacob Schor, ND, FABNO

Let me confess right up front that I made the decision to retire this past June, turning over the keys to our office to a pair of younger doctors.

Davis Lamson wrote me an email in late July to inform that it was his 85th birthday, and he candidly admitted he had never expected to reach such an age. He asked me whether I knew of any colleagues of a similar vintage still in practice. While I pondered his question, I threatened to throw him a belated birthday party during the AANP conference. Time has passed and some of us have aged, some more than others. That Davis Lamson seems to still be going strong is a thing of wonder to me. The concept that some people possess better genes must be true; his older brother still operates an auto repair shop.

We may lay claim to a long lineage of medical forebears, but the reality is that we are a young profession. We may count a few “old timers” who trained at earlier schools as colleagues, yet the vast majority of us are the products of National, Bastyr, and a few other subsequently created colleges. We have no ivy-covered campuses dating back centuries among our alma maters. We are still, for all intents and purposes, the first generation of modern naturopathic physicians.

We are not an overly affluent profession, and few among us have stashed away funds for retirement. The common response I hear from colleagues when queried about their “plans” is that they hope to emulate Dr Bastyr and practice until they die. While I’m all for optimism, this approach works better when you are young and idealistic enough to believe that naturopathic doctors will not succumb to the infirmities of aging. Such optimism is inversely proportional to age, and the older one gets, the less certain this sounds like a reliable plan.

Aging & Professional Decline

I realized awhile back that I wasn’t getting any smarter. Some of my friends will tell you I’ve been dumb and getting stupider for decades. The standard wisdom according to Dean Keith Simonton’s research is that success and productivity increase for the first 20 years after one starts a career. If you finished your naturopathic training when you were 30, your competence will peak at 50.1 From then on, it is downhill.

Benjamin Jones, who spent years studying when people are most likely to make prize-winning scientific discoveries or develop key inventions, reported in 2005 that the most common age for producing one’s big thing is the late 30s and that the likelihood of a major discovery increases steadily through one’s 20s and 30s but declines through one’s 40s, 50s, and 60s. The likelihood of producing a major innovation at age 70 is back down to what it was at age 20.2

This phenomenon isn’t restricted to the sciences. Simonton tells us that poets peak in their early 40s. Novelists peak a bit later; Martin Ortiz summarized data extracted from the New York Times fiction bestseller lists from 1960 to 2015, and concluded that authors are most likely to reach #1 on the bestseller list in their 40s to 50s.3 The chances of a 70-year-old writing a bestseller are low. (The exception is historians, who do peak later.) High-tech entrepreneurs peak even earlier. The Harvard Business Review reported in 2014 that the founders of tech enterprises valued at a billion dollars or more tend to cluster in the 20-34 age range.4 For air traffic controllers, performance decline is so significant that they are required to retire by age 56. Professional decline begins earlier than most of us realize, and without our notice. Professional decline, like entropy, appears to be a fundamental law in our universe.

I know for certain that I’m not as smart as I once was. I may have more experience and perhaps a small degree of hard-won wisdom, but my memory for numbers, facts, and the new study I may have read yesterday – all those have gotten harder. I can just barely access Netflix. Too much of what we need to do with patients requires the quick analytic capabilities of being able to see and comprehend the details of a problem while still maintaining an overview.

Crystallized Intelligence

The admonishment to “quit while you’re ahead” is not to be taken lightly. About 80 years ago Raymond Cattell, a British psychologist, devised an interesting pair of descriptions to classify the shifting ways we evaluate the world as we age. He said intelligence could either be fluid or crystallized. Fluid intelligence is the ability to reason, analyze, and solve novel problems – the sort of intelligence that innovators need. Crystallized intelligence is the ability to use knowledge gained in the past – the acquired library of experience, or what we might call wisdom. Careers and occupations that rely on fluid intelligence peak early, while those that rely on crystallized intelligence peak later. Poets tend to produce half of their lifetime creative output by age 40. Historians, by contrast, don’t reach this halfway mark until age 60.

For those in our profession, who expect to work late into life, we need to think about how best to transition away from work that relies primarily on fluid intelligence and toward the wisdom of crystallized intelligence and the strengths that persist later in life. Could this be why we see doctors starting to use the same general protocols with the majority of their patients over time?

College professors have perhaps the longest professional longevity of any profession. Research productivity may drop with age… But the best teachers and mentors tend to be in their mid-60s or older. At this point I had hoped to insert statistics about the ages of faculty at the naturopathic medical schools, along with the number of years they practiced before joining the faculty. Unfortunately, the school web pages don’t offer enough data to make those calculations. I can say, for what little it is worth, that a good portion of the faculty members look young. (Granted, pretty much everyone, aside from Davis, looks young to me.) That might just be healthy lifestyles at work – you know, that practice what you preach thing – but I suspect not.

This discussion reminds me of that Hindu concept of “ashramas,” or stages of life. With all the fascination with yoga these days, I assume our readers are familiar with this descriptive framework. Youth and young adulthood are called Brahmacharya, the period dedicated to learning. The second ashrama is Grihastha, during which a person builds a career, a family, accumulates wealth, and strives for earthly rewards. The third ashrama is Vanaprastha, which is Sanskrit for “retiring into the forest.” At this stage of life, people focus less on professional ambitions and turn toward a life devoted to spirituality, service, and wisdom. Vanaprastha is followed by Sannyasa, a life dedicated to enlightenment.

Many of my colleagues have reached this Vanaprastha stage, more focused on seeking wisdom and being of service to others than in advancing their careers, or at least they should be. This has happened quicker than many of us expected. And it’s catching our profession by surprise, and it’s not fully prepared. We have focused the profession’s attention and energy on the needs of our colleagues who are finishing their training and entering the Grihastha stage of life, helping them build their clinics, grow their practices, and pay off their loans, and we have all but ignored those who are retiring into the forest.

Here’s one measure of this: all of our professional organizations steeply discount membership dues for students and new graduates. None offer comparably steep discounts to doctors who have retired from practice. I know because I’ve reached out and asked the various organizations of which I have been a member and whose boards I have served on over the decades, “Do we have a retired membership category?” I’ve received near-identical responses from each: “We’ll make a note to discuss this at our next board meeting.” Six months later, I am letting my memberships lapse.

I’m not seeking patients, so I have no desire to be listed in any physician directory. No money coming in leaves me feeling leery to commit to paying further dues.

I accept the fact that I’m a critical person and can always find something to complain about. To balance out that feature of my personality, I’ve tried hard to help fix or at least improve whatever I’m unhappy with. That boils down to not allowing myself to complain out loud unless I’m willing to raise my hand and volunteer to work on the problem.

A Proposal for Empowering Retiring Docs

Here’s the problem as I see it. We have a generation of colleagues who are going to age out of practice, and perhaps in a way, they may be our profession’s best generation. These are the doctors who were called to the profession when it hardly existed – the ones who were willing to go to Kansas, the ones who envisioned what this profession might become. These are the most experienced and most committed among us, the doctors who built the profession from nearly nothing, who fought for our licensing laws, who lobbied to expand our scopes, who advanced the knowledge of our medicine. The way things stand now, we are going to lose them; they will slide into retirement and slip away from continuing to contribute.

In reality, they are at the point where they have the most to offer back. Rather than let them sneak off into the forests, we should be enlisting them to teach, to mentor, to provide the profession with the wisdom needed to provide direction in the future. We should be doing everything possible to keep them involved in their profession and to offer them opportunities to serve.

Every organization in our profession should have a membership category for retired doctors that is at least as discounted as what we offer students. Those who have paid full membership dues for 2 decades or more should need to pay nothing going forward to be listed as members. They have paid their dues. If we can discount conference registration fees for students, we should do the same for retired doctors. They don’t need the CE hours anymore, but will still come because they are part of the profession and want to contribute.

Asking them to pay full price when they no longer deduct business expenses from a limited income is rude. Most importantly, we need to open avenues for them to volunteer and contribute. Invite retired doctors to the schools. All those practices that took in student preceptors year after year? We owe those doctors more than gratitude; we owe them a channel through which they can continue to coach students. They just need a different setting to be of help.

Eulogy Virtues

David Brooks, the New York Times columnist, wrote in his 2015 book, The Road to Character, about this stage of life and this deep need to contribute and give back; he used 2 terms apparently of his own invention: He distinguished that Grihastha stage from the Vanaprastha stage as the difference between “resume virtues” and “eulogy virtues.”5 Resume virtues are the professional achievements that are linked to career success. They are the things we might write down in order to get ahead in life, things used to compare ourselves to others and make us look better. Eulogy virtues are the opposite of a competition. They are the things you would hope people remember and say about you at your funeral, the positive attributes you want to be remembered by.5

As a profession we need to make room for those of us who are graduating into the forest, those who care little for their resumes and who, if thinking about anything, are wondering who might write their eulogy. We need to create space for our most experienced practitioners – to volunteer to teach, to lobby, to train, and to create visions of our future.

References:

- Simonton DK. Creative Productivity: A Predictive and Explanatory Model of Career Trajectories and Landmarks. Psychol Rev. 1997;104(1):66-89. Available at: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.391.5108&rep=rep1&type=pdf. Accessed July 28, 2019.

- Jones BF. Age and Great Invention. May 2005. NBER Working Paper 11359. National Bureau of Economic Research. Available at: https://www.nber.org/papers/w11359.pdf. Accessed July 28, 2019.

- Ortiz MH. New York Times Bestsellers: Ages of Authors. May 2015. [Blog article] Available at: http://martinhillortiz.blogspot.com/2015/05/new-york-times-bestsellers-ages-of.html. Accessed July 28, 2019.

- Frick W. How Old Are Silicon Valley’s Top Founders? Here’s the Data. April 3, 2014. Harvard Business Review Web site. https://hbr.org/2014/04/how-old-are-silicon-valleys-top-founders-heres-the-data. Accessed July 28, 2019.

- Brooks D. The Road to Character. New York, NY: Random House; 2015.

Jacob Schor, ND, FABNO, graduated from NCNM in 1991 and has practiced in Denver, CO, ever since. He has been active in state association politics, taking his turn as president of the Colorado Association of Naturopathic Doctors and Legislative Chair. Dr Schor has also held leadership positions in the Oncology Association of Naturopathic Physicians, served on the AANP Board of Directors, and chaired the AANP’s speaker selection committee. For the past decade he has been the Associate Editor of the Natural Medicine Journal, and is a regular contributor to the Townsend Letter.

Jacob Schor, ND, FABNO, graduated from NCNM in 1991 and has practiced in Denver, CO, ever since. He has been active in state association politics, taking his turn as president of the Colorado Association of Naturopathic Doctors and Legislative Chair. Dr Schor has also held leadership positions in the Oncology Association of Naturopathic Physicians, served on the AANP Board of Directors, and chaired the AANP’s speaker selection committee. For the past decade he has been the Associate Editor of the Natural Medicine Journal, and is a regular contributor to the Townsend Letter.