Blended Learning

Our Trim Tab at Work in Naturopathic Medical Education

David J. Schleich, PhD

It has been said that if the Titanic had had a trim tab (a small flap on the back edge of the main rudder), the helmsman could have turned the boat faster and thus have avoided the right-side collision which flooded 5 of her 16 compartments (the Titanic would not have sunk, had it only been 4). In any case, the term “trim tab” has a particular currency and flair as a metaphor (Buckminster Fuller actually nicknamed himself “Trimtab”). A trim tab, though, has to be called into action at the right time and in the right place to really work. But work it will. The key is to keep the boat or plane’s speed and weight aligned with its trim tab in order to sustain a comfortable and efficient pitch attitude. The result is an ideal orientation for whatever conditions are prevailing. Let’s ponder curriculum delivery in this context.

The Convergence of Classroom & Communications Technology

Our “trim tab” metaphor is useful in contemplating just what we have to do in the naturopathic medical education arena, not only to avoid the icebergs with which we are all very familiar, but also to enhance our agility in a landscape where our detractors and competitors have bigger boats with bazookas, more fuel, and plenty of full-fare passengers. With our trim tab tools in hand, we can achieve agility and continuous momentum in the difficult passages of higher education and professional formation. We can build into our programs “deep and meaningful learning experiences” which “support engaged learners” (Garrison and Vaughan, 2008, p.ix) despite the stacked decks, to mix a metaphor.

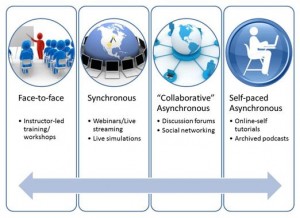

In such a world, the convergence of classroom and communications technology is very good “trim tab” for us, often referenced as “blended learning” (Figure 1). The literature demonstrates, as Marquis (2004) reported a decade ago, that “blended learning is more effective than classroom-based teaching alone.” Makhdoom et al (2013) took the declaration a step further, assessing its effectiveness in studying family medicine and clinical medical science. In their study (121 4th-year medical students at the clinical phase of a family medicine program), blending learning was found to be “statistically significantly better than traditional learning in all domains of the educational environment, except for social perception, and in all types of examination: written, objective structured clinical, and case scenarios” (Makhdoom, 2013). In their work, Makhdoom and colleagues remind us that so-called “e-learning” does not replace traditional instructor-led training, but “complements” it. Its availability (on demand) and its customizability were also noted in the study.

Figure 1. Blended Learning

source: http://cte.smu.edu.sg/blended-learning-programme/resources/

Teachable Examples

With regard to the appropriate use of blended learning for medical curricula, the following investigators are worth a look by our faculty leaders while thinking about how best to meet the needs of iPad-toting learners. Rowe, Frantz and Bozalek (2012), for example, have systematically reviewed the terrain of what was once called “electronically mediated instruction” [EMI] and is now referenced as “IT” [information technology]. They describe the main blended e-learning tools at work these days. The range is not surprising: taped lectures, flip classes, simulation software for most disciplines, and so on. Shaffer and Small (2004) investigated small group modules and didactic instruction for teaching radiologic anatomy. The remarkable span of high quality graphics and interactive materials was noted, along with the difficulty of keeping pace with new contributions and converting them into this format. Gordon et al (2005) studied the effectiveness of simulation-enhanced blended learning in the training of pre-hospital providers related to stroke training. Another notable observation was the ease of access for these busy professionals in search of current information. Taradi, Radic and Pokrajac (2005) undertook a similar study related to acid-phase physiology.

The following year, De Leng and colleagues checked in with medical students about their virtual learning environment experiences, with positive findings. Ruiz, Mintzer and Leipzig (2006) looked more broadly on the growing place of e-learning in medical education, concerned about the likely cost of training medical educators to convert their constantly evolving content into constantly evolving formats, reflective of student learning tools preferences.

Softwear Challenges in e-Learning

One element in e-learning which appears in the data is the necessity for savvy electronic course management system software challenges as students and their teachers navigate video conferencing, logbooks, discussion boards and email tools. Our world is one in which 80% of all American higher-education institutions and 93% of doctoral institutions offer hybrid or blended-learning courses (Arabasz & Baker, 2003)

This naturopathic medical education trim tab, blended learning, has the following key components, essential to its effective use:

- Connectivity. This means strong, reliable access to the web, primarily with mobile devices. Thus, learning becomes an “anytime, anywhere” event.

- Relevant course content. This means that student voice and choice in how they want to learn and present their learning is an omnipresent factor in their naturopathic medical education experience

- Engaging material. This means videos, blogging, inquiry-based questions, and more

- Collaboration. This means the opportunity for students and their teachers to work together to solve problems and to assist one another anytime, anywhere, digitally

- Feedback. This translates into teacher and peer feedback on blogs or other web sites

- Time Management. This means that students and their teachers must have a management system to optimize their time

A tall order? Well, yes. The meter is running on all fronts. We need all the trim-tab we can muster.

David J. Schleich, PhD is president and CEO of NCNM, former president of Truestar Health, and former CEO and president of CCNM, where he served from 1996 to 2003. Previous posts have included appointments as vice president academic of Niagara College, and administrative and teaching positions at St. Lawrence College, Swinburne University (Australia) and the University of Alberta. His academic credentials have been earned from the University of Western Ontario (BA), the University of Alberta (MA), Queen’s University (BEd), and the University of Toronto (PhD).

David J. Schleich, PhD is president and CEO of NCNM, former president of Truestar Health, and former CEO and president of CCNM, where he served from 1996 to 2003. Previous posts have included appointments as vice president academic of Niagara College, and administrative and teaching positions at St. Lawrence College, Swinburne University (Australia) and the University of Alberta. His academic credentials have been earned from the University of Western Ontario (BA), the University of Alberta (MA), Queen’s University (BEd), and the University of Toronto (PhD).

References

Arabasz, P., Baker, M.B. (2003). Evolving campus support models for e-learning courses. Educause Center for Applied Research. Retrieved from https://net.educause.edu/ir/library/pdf/ecar_so/ers/ers0303/ekf0303.pdf

de Leng, B.A., Dolmans, D.H., Muijtjens, A.M., van der Vleuten, C.P. (2006). Student perceptions of a virtual learning environment for a problem-based learning undergraduate medical curriculum. Med Educ, 40 (6), 568-575.

Garrison, D.R., Vaughan, N.D. (2008). Blended Learning in Higher Education: Framework, Principles, and Guidelines. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Gordon, D.L., Issenberg, S.B., Gordon, M.S., LaCombe, D., McGaghie, W.C., Petrusa, E.R. (2005). Stroke training of prehospital providers: an example of simulation-enhanced blended learning and evaluation. Med Teach, 27 (2), 114-121.

Kvavik, R.B., Caruso, J.B. (2005). ECAR study of students and information technology, 2005: Convenience, connection, control, and learning. Research Study from EDUCAUSE Centre for Applied Research. Retrieved October 17, 2005, from http://www.educause.edu/ers0506/

Makhdoom, N., Khoshhal, K.I., Algaidi, S., Meissam, K. Zolaly, M.A. (2013). ‘Blending learning’ as an effective teaching and learning strategy in clinical medicine: a comparative cross-sectional university-based study. Journal of Taibah University Medical Sciences, 8 (1). Retrieved January 24, 2014, from http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1658361213000036

Rovai, A.P., Jordan, H.M. (2004). Blended learning and sense of community: A comparative analysis with traditional and fully online graduate courses. The International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 5 (2). Retrieved December 14, 2005 from http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/192/274

Rowe, M., Frantz, J., Bozalek, V. (2012). The role of blended learning in the clinical education of healthcare students: a systematic review. Med Teach, 34, 216-221.

Ruiz, J.G., Mintzer, M.J., Leipzig, R.M. (2006). The impact of e-learning in medical education. Acad Med, 81 (3), 207-212.

Shaffer, K., Small, J.E. (2004). Blended learning in medical education: use of an integrated approach with web-based small group modules and didactic instruction for teaching radiologic anatomy. Acad Radiol, 11 (9), 1059-1070.

Taradi, S.K., Taradi, M., Radic, K., Pokrajac, N. (2005). Blending problem-based learning with web technology positively impacts student learning outcomes in acid–base physiology. Adv Physiol Educ, 29 (1), 35-39.

Vaughan, N., Garrison, D.R. (2006a). How blended learning can support a faculty development community of inquiry. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 10 (4), 139-152.