ALAN CHRISTIANSON, NMD

Women in their late 30s to early 60s make up most naturopathic patients. This article will give naturopathic physicians insights on iodine that may help them assist their patients even more. In this paper, I will show that the smallest deviation in iodine can cause thyroid disease and that correcting that deviation may reverse it.

Adult women are more prone to thyroid disease than men.1 There are 4 leading theories to explain this: fetomaternal microchimerism,2 X-linked genetic susceptibility,3 androgenic suppression of cellular immunity,4 and gender differences in the sodium iodide symporter.5

The first is a result of a normal pregnancy; there are no ideas on how it could be prevented. The second and third are also unchangeable. The last theory – gender differences in the sodium iodide symporter – is the only one that we can do something about.

New evidence shows that the sodium iodide symporter (NIS) is influenced by iodine intake. Regulating iodine to modulate NIS function can lower the risk of developing thyroid disease and, in some cases, can reverse the disease even after it is established.

The degree of the problem is amplified by how dissatisfied patients are with current thyroid treatments.6 A large survey was conducted on over 12 000 women between the ages of 30 and 60 years who had thyroid disease. The results showed that:

- <7% of respondents were “very satisfied” with their treatment

- 71% had changed doctors multiple times

- 15% of had seen 6 or more different doctors

Patients are looking for guidance on dietary interventions as well as a prescriber to help them pursue thyroid replacement beyond T4-only medication. Naturopathic physicians are uniquely positioned to help with diet and biocompatible treatment options.

The Iodine Opportunity

We can help our patients so much more if we consider diet and medication in the context of our patients’ iodine status. This article will give you an overview of the connection between iodine and thyroid disease, share the latest insights from research, and suggest sources for further study.

Iodine can be tricky. People who think with nuance have an easier time understanding it. Iodine is neither “good” nor “bad.” It is essential to thyroid function, yet too much iodine can hurt the thyroid. Exactly where are the boundaries of too little and too much? And where in this continuum do most adults with thyroid disease fall?

In the last decade, we’ve learned a lot. Not much has changed about the lower boundary – people do not require more iodine than we thought. However, the upper limit has changed. It turns out that getting too much is easier than we thought. This can happen because some people tolerate much less iodine than others and because extra iodine can come from unexpected sources.

The other new insight is that the thyroid can fix itself better than we thought.

Before we get into the details, I’d like to ask a favor. I’m asking because some of what you will read in this article might differ from what you have previously heard. If it does differ, some of you might accept the new perspective without question, but many of you might reject it. I’m asking you to do neither, but to spend some time reading primary sources.

We have a vast body of knowledge about iodine, which encompasses over 22 000 studies. You might be surprised by how many popular ideas do not comport with this body of literature. Start your inquiry with some systematic reviews or meta-analyses, if possible. Then, read enough individual papers on the topic until you can tell which studies represent the body of knowledge and which ones are outliers. If you go deeply into it and arrive at a different conclusion, please let me know.

Iodine Basics

Iodine enters our bodies through food, water, across our skin, and even from the air!7-9 Before entering our bodies, it may arrive as various forms of iodides, iodates, molecular iodine, or monoatomic iodine. Regardless of the initial type, when it contacts our tissues it is reduced to iodide before entering the circulation.10

Our thyroid is made up of specialized thyrocytes that are organized into hollow clusters called thyroid follicles. The cells lining the follicles produce a large protein called thyroglobulin, which they secrete into the lumen.

Iodide is concentrated within the thyroid follicles of the thyroid gland via an active transport protein called the sodium iodide symporter, or the NIS. Within the follicles, the oxidation of iodide into the highly volatile form of iodine is facilitated by the enzyme thyroid peroxidase.

The newly oxidized iodine quickly attaches to specific tyrosol residue sites on thyroglobulin.11 In states of iodine sufficiency, each molecule of thyroglobulin contains 8-10 atoms of iodine.

How Iodine Can Cause Thyroid Disease

Any well-established idea in medicine should be represented by all lines of evidence: mechanistic models, epidemiologic surveys, and interventional trials. I’ll use each of these lines to illustrate the emerging ideas about iodine.

Mechanisms

In short, extra iodine slows the thyroid and also triggers the immune system. It slows the thyroid directly by blocking the intake of material to the thyroid follicle, downregulating the NIS, decreasing thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) receptor response, and inhibiting thyrocyte generation.12

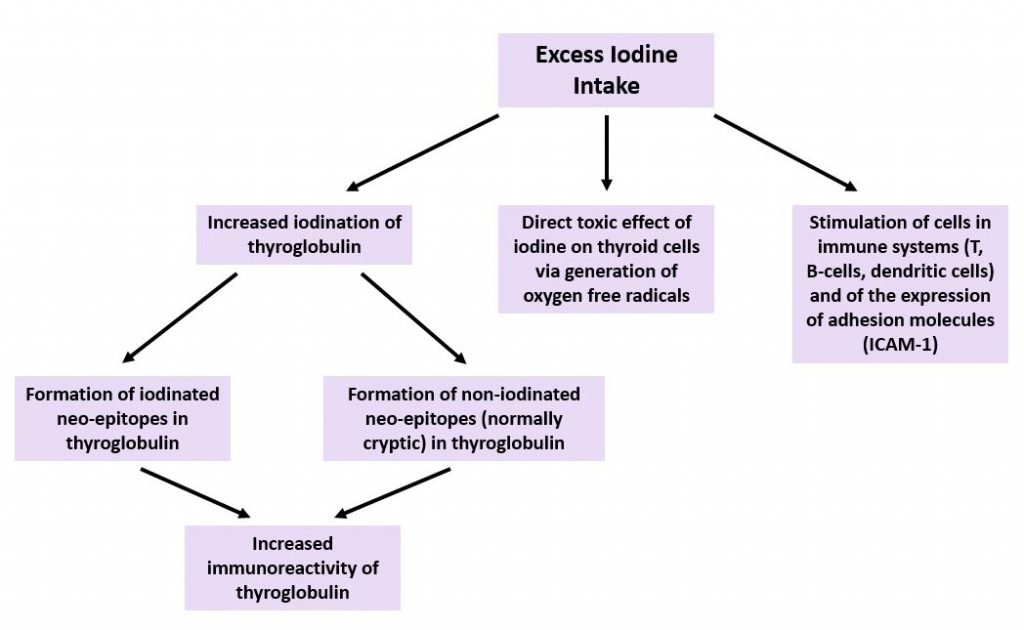

Autoimmune thyroid disease emerges when lymphocytes are activated against thyroid peroxidase and/or thyroglobulin. The main series of events behind this activation is a cycle brought on by chronic excessive iodine intake.13,14

When iodine intake is excessive, as many as 60 iodine atoms can attach to each molecule of thyroglobulin. Animal studies have shown that extra iodine attaches to secondary tyrosol sites, forming neo-epitopes that increase the antigenicity of thyroglobulin.15 The NIS is inhibited as a result of the iodine excess, and thyrotropin is elevated.16

Animal, human, and in-vitro studies have shed light on the process. Free radicals form due to the unattached iodine. Thyroid cells become inflamed and the basal rate of apoptosis is elevated. As thyrocytes die, lymphocytes are activated and enter the thyroid follicles.17,18 These lymphocytes attack thyroglobulin and thyroid peroxidase.19 With enough repetition, this immune attack becomes chronic.20

A summary of these mechanisms is displayed in Figure 1.

Epidemiologic Evidence

When iodine intake increases by even small amounts, populations see increases in autoimmune thyroid disease. The United States started an elective iodine fortification system in 1924.22 At the time of fortification, the case morbidity rate for autoimmune thyroid disease in women over the age of 40 was 2.1 per 100 000. In the years following fortification, the case morbidity rate increased 25.7-fold.23

Similar trends have been seen in the more recent past, as displayed in Table 1.

Table 1. Iodine Fortification & Thyroid Autoimmunity24

| Country | Year of Iodine Fortification | Change in AITD |

| China | 2002 | 289% ↑↑ |

| Denmark | 2000 | 53% ↑↑ |

| Australia | 1998 | 64% ↑↑ |

| Hungary | 1998 | 950% ↑↑ |

| Poland | 1997 | 300% ↑↑ |

| Zimbabwe | 1995 | 300% ↑↑ |

| Spain | 1994 | 240% ↑↑ |

Interventional Trials

Placebo-controlled studies have demonstrated that supplemental iodine can trigger autoimmune thyroid disease (AITD). One such study showed that when iodine supplements are given, as little as 100 µg of extra iodine can change thyroid function in those with no history of thyroid disease, in as little as 4 weeks.25 Another randomized placebo-controlled study showed that administration of 200 µg per day of iodine to euthyroid individuals with endemic goiter induced AITD in approximately 10% of the cases.26

Even a single iodine-rich meal high can cause a measurable increase in TSH.27

How Iodine Regulation May Reverse AITD

It has been assumed that the process of AITD inevitably progresses once it starts. New evidence suggests that this is not necessarily the case.

Nearly all of the iodine secreted by the thyroid gland is packaged within thyroid hormones. The thyroid can eliminate non-hormonal iodine, but not very quickly. It also cannot eliminate non-hormonal iodine when systemic levels of iodine are above a certain threshold.28

Once the thyroid follicles have reached a critical state of iodine excess, it may only take modest iodine intakes to prevent a return to iodine homeostasis. However, if a low enough amount of iodine is consumed, a gradient between systemic iodine and thyroidal iodine can be created. This gradient can allow the thyroid to resume a sustainable supply of iodine. When this happens, thyrocytes may repair and autoimmunity may reverse, as happened to participants in the following interventional trials.

Interventional Trials

In the earliest study, conducted in Japan, a group of patients with primary hypothyroidism were put on a regulated iodine diet for 8 weeks.29 The patients’ median age was 52 years and their average TSH level was 21.9 IU/mL. Roughly half of the patients showed evidence of elevated thyroid antibodies. The only intervention was the avoidance of iodine – from supplements, medications, and foods with high amounts.

By the end of 8 weeks, 72% of participants saw their TSH score lower by 50%, and most participants (63.6%) regained normal thyroid function. Four out of 5 non-responders did not show a decrease in their blood or urinary iodine levels. The investigators’ interpretation was that they chose not to be compliant or had hidden sources of iodine they were not aware of. There was only 1 participant who did successfully reduced their iodine intake yet still saw an improvement in thyroid function.29

A follow-up study was done on a group of 45 patients, average age 41 years, all of whom were hypothyroid secondary to Hashimoto’s thyroiditis.30 The patients were randomly assigned to a control group or a group given an iodine-regulated diet. The patients had suffered thyroid disease between 2.1 and 4.2 years, and their average TSH score was 14.28 IU/mL.

Within 3 months, 78.3% of those on the iodine-regulated diet had normal thyroid function, with an average TSH score of 3.18 IU/mL. No such change was seen in the control group. Of those who did not achieve normal thyroid function, 80% improved by over 50%. Many of them had initial TSH levels as high as 50 or 200 IU/mL. The researchers projected that, given additional time, many of them likely would have recovered. Only 4% of participants failed to respond in any way. Interestingly, the pre-trial iodine levels did not predict who would respond, but post-trial iodine levels predicted who would not.30

Practical Applications

Iodine regulation may thus be helpful to your patients with thyroid disease. Even for those on thyroid medication, iodine regulation may help them lower their TSH resistance and encourage thyrocyte regrowth.31

When counseling your patients about iodine regulation, consider both visible and invisible sources of iodine.

Visible Sources of Iodine:

- Medications

- Thyroid medication

- NDT (natural dessicated thyroid): 0.002 µg iodine per mg of NDT

- T4 (levothyroxine): 0.65 µg iodine per µg of active hormone

- T3 (liothyronine): 0.35 µg iodine per µg of active hormone

- Amiodarone

- Radiographic contrast agents

- Topical antiseptics

- Supplements

- Multivitamins (may contain 2-3-fold the labeled amount)32

- Iodine supplements

- Thyroid support products

- Iodized salt

- Sea vegetables

- Kelp

- Nori

- Wakame

Invisible Sources of Iodine:

- Cosmetics with iodine-based ingredients33

- Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP)

- TEA-hydroiodide

- Ethiodized oil

- Mammalian milk products (cow, sheep, goat, camel)

- Milk

- Cheese

- Yogurt

- All commercial grain products (including gluten-free)

- Some non-iodized salt

- Pink Himalayan salt

- Sea salt (most brands)

Please anticipate that your patients on thyroid medication who do see improvements in endogenous thyroid output as a result of iodine moderation will need prompt reductions in their dosage to prevent hyperthyroid complications. In most cases, it is safe to wait for 4 weeks before retesting; however, some patients may have hyperthyroid symptoms manifest more quickly and will thus need earlier intervention.

Talk to your thyroid patients about iodine intake. You may be surprised by how much iodine they are exposed to and how much it can help to avoid hidden sources of it.

Where to Learn More:

The Thyroid Reset Diet (publication date: January 23, 2021)

- Nutritionally complete, iodine-regulated meal plans and recipes with Paleo and vegan options

- How to accurately test for iodine

- Why is there an iodine controversy?

Iodinefacts.org

- Searchable comprehensive database of the iodine content of foods.

Iodine Inventory

- App that allows users to track their daily iodine intake.

References:

- Lu Y, Li J, Li J. Estrogen and thyroid diseases: an update. Minerva Med. 2016;107(4):239-244.

- Cirello V, Rizzo R, Crippa M, et al. Fetal cell microchimerism: A protective role in autoimmune thyroid diseases. Eur J Endocrinol. 2015;173(1):111-118.

- Invernizzi P, Miozzo M, Selmi C, et al. X chromosome monosomy: a common mechanism for autoimmune diseases. J Immunol. 2005;175(1):575-578.

- Wilder RL. Neuroendocrine-immune system interactions and autoimmunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 1995;13:307-338.

- Ryan J, Curran CE, Hennessy E, et al. The sodium iodide symporter (NIS) and potential regulators in normal, benign and malignant human breast tissue. PLoS One. 2011;6(1):e16023.

- Peterson SJ, Cappola AR, Castro MR, et al. An Online Survey of Hypothyroid Patients Demonstrates Prominent Dissatisfaction. Thyroid. 2018;28(6):707-721.

- Leung AM, Braverman LE. Consequences of excess iodine. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2014;10(3):136-142.

- Smyth PP, Burns R, Huang RJ, et al. Does iodine gas released from seaweed contribute to dietary iodine intake? Environ Geochem Health. 2011;33(4):389-397.

- Erdoǧan MF, Tatar FA, Ünlütürk U, et al. The effect of scrubbing hands with iodine-containing solutions on urinary iodine concentrations of the operating room staff. Thyroid. 2013;23(3):342-345.

- Bürgi H, Schaffner T, Seiler JP. The toxicology of iodate: A review of the literature. Thyroid. 2001;11(5):449-456.

- Coscia F, Taler-Verčič A, Chang VT, et al. The structure of human thyroglobulin. Nature. 2020;578(7796):627-630.

- Calil-Silveira J, Serrano-Nascimento C, Kopp PA, Nunes MT. Iodide excess regulates its own efflux: A possible involvement of pendrin. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2016;310(7):C576-C582.

- Champion BR, Rayner DC, Byfield PG, et al. Critical role of iodination for T cell recognition of thyroglobulin in experimental murine thyroid autoimmunity. J Immunol. 1987;139(11):3665-3670.

- Fiore E, Latrofa F, Vitti P. Iodine, thyroid autoimmunity and cancer. Eur Thyroid J. 2015;4(1):26-35.

- Bagchi N, Brown TR, Urdanivia E, Sundick RS. Induction of autoimmune thyroiditis in chickens by dietary iodine. Science. 1985;230(4723):325-327.

- Koukkou EG, Roupas ND, Markou KB. Effect of excess iodine intake on thyroid on human health. Minerva Med. 2017;108(2):136-146.

- Braley-Mullen H, Sharp GC, Medling B, Tang H. Spontaneous autoimmune thyroiditis in NOD.H-2h4 mice. J Autoimmun. 1999;12(3):157-165.

- Many MC, Maniratunga S, Varis I, et al. Two-step development of Hashimoto-like thyroiditis in genetically autoimmune prone non-obese diabetic mice: Effects of iodine-induced cell necrosis. J Endocrinol. 1995;147(2):311-320.

- Kawashima A, Tanigawa K, Akama T, et al. Innate immune activation and thyroid autoimmunity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(12):3661-3671.

- Kawashima A, Tanigawa K, Akama T, et al. Fragments of genomic DNA released by injured cells activate innate immunity and suppress endocrine function in the thyroid. Endocrinology. 2011;152(4):1702-1712.

- Ferrari SM, Fallahi P, Antonelli A, Benvenga S. Environmental Issues in Thyroid Diseases. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2017;8:50. Published 2017 Mar 20. doi:10.3389/fendo.2017.00050

- Leung AM, Braverman LE, Pearce EN. History of U.S. iodine fortification and supplementation. Nutrients. 2012;4(11):1740-1746.

- Furszyfer J, Kurland LT, Woolner LB, et al. Hashimoto’s thyroiditis in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1935 through 1967. Mayo Clin Proc. 1970;45:586-596.

- Sun X, Shan Z, Teng W. Effects of Increased Iodine Intake on Thyroid Disorders. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul). 2014;29(3):240-247.

- Sang Z, Wang PP, Yao Z, et al. Exploration of the safe upper level of iodine intake in euthyroid Chinese adults: a randomized double-blind trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;95(2):367-373.

- Kahaly G, Dienes HP, Beyer J, Hommel G. Randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled trial of low dose iodide in endemic goiter. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82(12):4049-4053.

- Noahsen P, Kleist I, Larsen HM, Andersen S. Intake of seaweed as part of a single sushi meal, iodine excretion and thyroid function in euthyroid subjects: a randomized dinner study. J Endocrinol Invest. 2020;43(4):431-438.

- Sato K, Okamura K, Yoshinari M, et al. Reversible primary hypothyroidism and elevated serum iodine level in patients with renal dysfunction. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh). 1992;126(3):253-259.

- Kasagi K, Iwata M, Misaki T, Konishi J. Effect of iodine restriction on thyroid function in patients with primary hypothyroidism. Thyroid. 2003;13(6):561-567.

- Yoon SJ, Choi SR, Kim DM, et al. The effect of iodine restriction on thyroid function in patients with hypothyroidism due to Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Yonsei Med J. 2003;44(2):227-235.

- Furlanetto TW, Nguyen LQ, Jameson JL. Estradiol increases proliferation and down-regulates the sodium/iodide symporter gene in FRTL-5 cells. Endocrinology. 1999;140(12):5705-5711.

- Patel A, Lee SY, Stagnaro-Green A, et al. Iodine content of the best-selling United States adult and prenatal multivitamin preparations. Thyroid. 2019;29(1):124-127.

- Cosmetics Info. PVP-Iodine. 2016. Available at: https://cosmeticsinfo.org/ingredient/pvp-iodine-0. Accessed July 15, 2020.

Alan Christianson, NMD is a New York Times bestselling author whose latest book is The Thyroid Reset Diet. Dr Christianson is the founding physician behind Integrative Health, based in Scottsdale, AZ, and is the founding president of the Endocrine Association of Naturopathic Physicians. He is an alumnus from the first graduating class of Southwest College of Naturopathic Medicine.