Jennifer Brusewitz, ND

The number of patients who present to the physician with digestive issues is formidable. The most common complaints—gas, bloating, constipation, reflux, and abdominal pain—are not surprising considering the diet and eating patterns that predominate in our culture. We have strayed far from our ancestral food ways, resulting in digestive discomfort and in inflammation and poor nutrient assimilation. As NDs, we can introduce our patients to culinary traditions that support optimal digestion and have a profound effect on overall health.

Bitters Before Meals

In many culinary traditions, including those in Europe and Asia, bitter herbs were used to strengthen digestion and to tonify the entire gastrointestinal tract.1 The use of bitters increases the production of enzymes, reducing bloating and aiding the breakdown of food and the assimilation of nutrients. Bitter taste receptors on the tongue are stimulated, and a critical cascade of digestive events follows, including a release of the gastric hormone gastrin and the immediate production of salivary enzymes. Gastrin causes hydrochloric acid to be released in the stomach, which breaks down proteins and increases absorption of many minerals, including calcium, magnesium, and iron. Pepsin is also released and is responsible for breaking down large protein molecules into peptides and amino acids. Intrinsic factor is released, which is necessary for the absorption of vitamin B12.

Widespread use of proton pump inhibitors, H2 blockers, and antacids may deplete nutrients in our patients. Bitters induce the constriction of the upper esophageal sphincter, supporting the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease and lessening the need for pharmaceutical acid blockers. Bitters increase the production of bile in the liver and the excretion of bile by the gallbladder. Bile breaks down dietary fats and facilitates the absorption of fat-soluble vitamins A, D, and E. These processes, and many more, would be hindered without adequate stomach acid. Bitters not only dramatically aid the digestive process but also facilitate the absorption of essential nutrients.

Bitter greens in first-course salads and aperitifs or bitter alcoholic drinks consumed before meals increase saliva production and induce appetite.2 Greens like chicory, arugula, dandelion leaves, radicchio, and endive can be mixed with lettuce as a start to a meal. Dressings made with the sour flavors of lemon juice and vinegar also help promote the production of digestive enzymes and stimulate the liver. An additional way to prescribe bitters is by formulating a combination bitters tincture to be taken 15 to 30 minutes before meals, which may be combined with warming, aromatic, or soothing herbs to optimize digestion. Some examples of herbs for a bitters combination include Gentiana lutea, Arctium lappa, Humulus lupulus, Angelica archangelica, Zingiber officinale, Taraxacum officinale, Matricaria chamomilla, Elettaria cardamomum, Foeniculum vulgare, and Scutellaria lateriflora. Bitter herbs can be combined with a small amount of water or may be taken directly on the tongue.

Fermented Foods

Fermented foods are found in abundance within the diets of many traditional cultures, providing probiotics, enzymes to support digestion, and nutrients to promote healing of the cells in the digestive tract. Fermenting of foods was used as early as 9000 bc and is one of the world’s oldest preservation methods, second only to drying.3 In the process of fermentation, probiotic bacteria consume the starches and sugars within the food, and the metabolites produced include lactic acid. Lactic acid inhibits pathogenic bacteria from propagating, thus preserving food. Lactic acid–producing bacteria in our intestines also deter overpopulation of pathogenic bacteria, and while probiotic supplements can be supportive to that end, we can look at the dietary habits of our ancestors to see an abundance of microbes in their diets.

A small Finnish study4 published in 2011 showed a correlation between intestinal pain and a 5-fold reduction in bifidobacteria. In patients with digestive distress, fermented foods supply probiotics and nutrients that heal an inflamed intestinal lining, and they provide lactic acid to fend off pathogenic intruders that may cause bloating and pain. Cabbage in the fermented foods sauerkraut and kimchi contains the amino acid glutamine, a nutrient needed for healing of the enterocyte cells of the small intestine. Kimchi, a Korean dish of spicy fermented bok choy cabbage, has been studied extensively in Korea and is well known for supporting digestion and immunity.

The microflora of a healthy intestinal tract are responsible for fermenting soluble fibers from our diet into butyric acid, a short-chain fatty acid that is an essential energy source for colonic mucosal cells and may reduce intestinal barrier permeability.5 Recommending raw and lightly steamed fruits and vegetables is a way to increase butyric acid, and specific sources of foods high in insoluble fiber include fruit with the skins, root vegetables, Brassica family vegetables, green leafy vegetables, nuts, and seeds. Butyrate is known to be a potent anti-inflammatory agent,6 and oral butyrate and butyrate enemas are used to reduce colonic bleeding in patients during exacerbations of ulcerative colitis.7 Butter contains 4% butyric acid and is another food source to recommend, preferably obtained from the milk of grass-fed cows for optimal fat-soluble vitamin content.

The hygiene hypothesis8 purports that there has been a continual reduction in exposure to bacteria, fungus, and parasites since industrialization, resulting in underdevelopment of human immunity. Factors involved include reduction in childhood diseases, greater use of antibiotics, and a general increase in hygienic practices, diminishing exposure to microorganisms during immune system development. This issue is compounded by the industrialization of our food supply, which begets ultraprocessed nutrient-depleted foods. Fruits and vegetables from healthy soil contain traces of the beneficial bacteria from the soil they came from, so encouraging patients to acquire their produce from small organic farms further promotes optimal nutrition. Recommending a small amount of fermented vegetables with meals benefits digestion and robust immunity.

Bone Broth

Bone broths, a universal staple in traditional diets, are nutrient dense and are especially supportive for the digestive tract. Broths are made by using the bones of meat, poultry, and fish and contain nutrients extracted from the bone, cartilage, and marrow. Combining bones, water, and some kind of acid in the form of vinegar or wine produces a rich, medicinal, and tasty broth.9 Bone broths contain gelatin, replete with the amino acids arginine and glycine, as well as calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, potassium, glucosamine, and chondroitin. In the early 1900s, researcher, author, and gelatin champion C. A. Herter suggested that the gelatin in bone broth increases absorption of essential nutrients to the cells of the intestines and soothes an inflamed lining, while reducing the carbohydrate fermentation due to bacterial infections of the gut.10

In the past, meats were sold on the bone and were readily available to make broths and stocks. Although modern meat processing techniques have reduced their availability, bones are still accessible at most meat counters. Patients should be encouraged to make bone broth and drink it before meals, as well as to use bones as the base for soups and cooking liquid for grains.

The following is a recipe for bone broth:

- Obtain bones from poultry, beef, lamb, or fish.

- Cover with water in a pot and add a splash (1-2 tablespoons) of apple cider vinegar, wine, or lemon juice and 1 to 2 teaspoons of unprocessed mineral-rich salt (eg, Real Salt [http://www.realsalt.com], Himalayan Crystal Salt [http://www.himalayancrystalsalt.com], or Celtic Sea Salt [http://www.celticseasalt.com]).

- Add carrots, onions, celery, herbs, and spices as desired.

- Cook 4 to 24 hours at low simmer on the stove or in an electric cooking pot on low. After cooking, remove the bones and skim the fat. Broth keeps in the refrigerator for 5 days and in the freezer for many months.

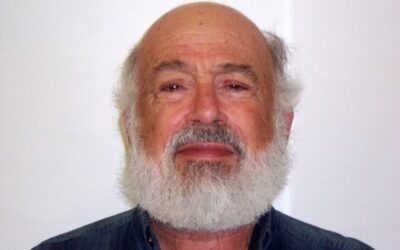

Weston Price, DDS

There is in increasing interest in traditional food ways, and many can be used clinically to treat poor digestion, gastrointestinal inflammation, and diminished nutrient assimilation. Thanks to the passionate curiosity of Weston Price, DDS,11 we are able to read about the diets of a diverse number of primitive cultures. After observing increasing dental issues in his patients, Dr Price was drawn to study cultures around the world that still practiced their traditional food ways. In the early part of the 20th century, Price traveled to numerous societies across the globe and observed excellent dental and overall health. He analyzed hundreds of food samples from various cultures and found that traditional foods contained 10 to 50 times the nutrient content of diets back home in America. He found that indigenous cultures had practices that provided foods that were vitamin and mineral rich, were easily digested, and contributed to bountiful gut bacteria.

Appreciation for food quality and preparation can support optimal digestion. Taking our meals in a relaxed environment is also important. When under stress, the sympathetic mode dominates our nervous system, reducing blood flow to the digestive organs, affecting contractions of the digestive smooth muscle, and decreasing the enzymes needed for digestion. Empower patients with recommendations that allow them to connect to food in the ways of our ancestors, tapping into their innate wisdom and excellent health. Encourage patients to light the candles, say a blessing, and linger over meals to allow the full digestive process to unfold.

Jennifer Brusewitz, ND is a 2000 graduate of the National College of Naturopathic Medicine, Portland, Oregon. She currently practices in Portland and is a clinical supervisor at NCNM’s teaching clinics. She also investigates, develops, and implements quality assurance standards in the NCNM Medicinary.

Jennifer Brusewitz, ND is a 2000 graduate of the National College of Naturopathic Medicine, Portland, Oregon. She currently practices in Portland and is a clinical supervisor at NCNM’s teaching clinics. She also investigates, develops, and implements quality assurance standards in the NCNM Medicinary.

References

- Hobbs C. Foundations of Health: The Liver and Digestive Herbal. Capitola, CA: Botanical Press; 1992.

- Charles-Davies D. Bitters: the revival of a forgotten flavor. Wise Traditions in Food, Farming and the Healing Arts. January 2011;16:25.

- Farnsworth E. Handbook of Fermented Functional Foods. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2003.

- Jalanka-Tuovinen J, Salonen A, Nikkilä J, et al. Intestinal microbiota in healthy adults: temporal analysis reveals individual and common core and relation to intestinal symptoms. PLoS One. 2011;6(7):e23035. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21829582. Accessed September 15, 2011.

- Mullin G. Integrative Gastroenterology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2011.

- Meijer K, de Vos P, Preibe MG. Butyrate and other short-chain fatty acids as modulators of immunity: what relevance for health? Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2010;13(6):715-721.

- Lawrance IC. Topical agents for idiopathic distal colitis and proctitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26(1):36-43.

- Strachan DP. Hay fever, hygiene, and household size. BMJ. 1989;299(6710):1259-1260.

- Fallon S. Nourishing Traditions: The Cookbook That Challenges Politically Correct Nutrition and the Diet Dictocrats. 2nd ed. Warsaw, IN: New Trends Publishing; 1999.

- Henderson LJ, Forbes A. On the estimation of the intensity of acidity and alkalinity with dinitrohydroquinone. J Am Chem Soc. 1910;32(5):687-689.

- Price W. Nutrition and Physical Degeneration. 6th ed. La Mesa, CA: Price-Pottenger Nutrition Foundation; 1939.