Tolle Causam

Gaia Mather, ND

Constipation is a problem that will affect nearly every patient at some time in their lives. According to Goodheart and Leavitt,1 functional constipation affects 12% to 19% of the American population. Whether due to a transient change in diet when traveling or as part of a symptom picture of a larger diagnosis or the adverse effect of a new medication, constipation is not merely an inconvenience but has the potential for seriously affecting a patient’s quality of life: “[Constipation] is one of the most frequent reasons for self-medication, with at least $800 million spent annually for laxatives. In the United States alone, treatment for constipation accounts for more than 2.5 million doctor visits annually.”2

The treatment of constipation becomes particularly important with patients who are placed on opioid pain medications. The effects of opiates on the gastrointestinal tract are well known, and the resulting constellation of symptoms is termed opioid-induced bowel dysfunction (OBD): “Signs and symptoms of OBD shared in common with functional constipation include: dry hard stools, straining during evacuation, incomplete evacuation, bloating, abdominal distension, and retention of contents of the gut. Unlike functional constipation, OBD also can include cramping, nausea and vomiting, and gastric reflux.”1(p2-3) In the gut, opioid analgesics target the k receptors affecting bowel motility. From the stomach downward, opioids have effects on every part of the gut. In the pyloric region, gastroparesis from spasming causes delayed gastric emptying. Transit time in the small intestine is elongated due to an increase in spasmodic nonpropulsive motility. This effect is most pronounced in the jejunum.1-4 In the large intestine, “Increased contractions of circular muscles cause non-propulsive kneading and churning, increasing fluid absorption, which dries and hardens the stool. At the same time, longitudinal propulsive peristalsis is decreased, providing additional time for drying of the stool. In addition to these effects, anal sphincter tone is increased, so reflexive relaxation in response to rectal distension is reduced making defecation more difficult.”1(p3)

Constipation as an adverse effect of opioid use is almost universal: “In one study, 95% of patients interviewed by nurses in a hospital oncology unit reported constipation as the major side effect of their opioid pain-control regimen.”1(p3) Patients being prescribed these medications, whether short term or ongoing, should be evaluated for a history of constipation. Many patients self-medicate for their constipation and do not think to mention this to their physicians. The BC Cancer Agency’s symptom management guidelines3 for nurses on constipation give a very complete overview of the topic, including causative factors, consequences of untreated constipation, clinical assessment (with history and physical examination), and strategies for the overall management of constipation.

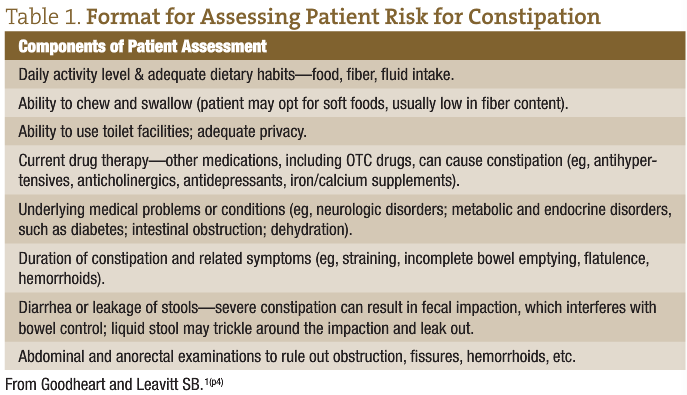

Patients and physicians are hesitant to discuss the subject of constipation. However, it is vital to establish a baseline of information about a patient’s bowel habits, if possible, before opioid therapy is initiated. In their article “Managing Opioid-Induced Constipation in Ambulatory-Care Patients,” Goodheart and Leavitt1 provide another format for assessing patient risk for constipation (Table 1):

In her article titled “Preemptive Treatment of Constipation When Opioids are Initiated,” Mary Ann Zagaria addresses the risks of obstinate constipation: “Why is the issue of preemptive treatment of constipation when commencing treatment with opioids so significant? The increased risk of fecal impaction as a complication of constipation in long-term care residents (occurring in about 30%) may precipitate hospital admissions.”2 She also notes: “…FI [fecal impaction] can obstruct the bowel, and if not rapidly treated, may result in inadequate blood flow to the bowel (bowel ischemia) and bowel perforation requiring emergency treatment and hospitalization.”2

Opioid-induced bowel dysfunction and its accompanying effects can have a serious impact on a patient’s quality of life. In a large Internet-based study, patients taking daily oral opiate medications and laxatives completed a questionnaire: “At the time of the survey, 45% of patients reported <3 bowel movements per week. The most prevalent opioid-induced side effects were constipation (81%) and straining to pass a bowel movement (58%). Those side effects considered most bothersome by patients were (in order of rank) constipation, straining, fatigue, small or hard bowel movements, and insomnia.”5(p35) The authors continued, describing the negative impact these symptoms had on the patients’ quality of life and activities of daily living: “A third of patients had missed, decreased or stopped using opioids in order to make it easier to have a bowel movement.”5(p35) Several articles4,6-8 have noted the incidence of patients’ decreasing or discontinuing pain medications due to decreased quality of life. It is important to note, however, and to make clear to your patients that “[u]sing lower doses of opioids will not prevent constipation because the dose that produces constipation is approximately 4-fold less than the analgesic dose.”1(p4)

The currently suggested standard of care for patients undergoing an opiate-based pain protocol is to start the patient with a stool softener on a daily basis, while adding in a stimulant laxative as needed. Examples of stimulant laxatives are aloe, cascara, and senna, including brand name over-the-counter senna and bisacodyl products. Several sources1,2,3,9 recommend starting a combination of a stimulant laxative with a stool softener (such as docusate sodium). Stimulant laxatives act to increase gut peristalsis and motility, which is suppressed by the action of the opiates, while the stool softener holds water in the intestinal lumen to soften dry hard stool. The BC Cancer Agency’s outpatient bowel protocol summary9 gives a stepwise guide to patients for laxative use. It suggests starting with 2 sennosides tablets at bedtime. If the patient has no bowel movement (BM) after 2 days, 2 sennosides tablets are taken in the morning as well. If no BM occurs by the next day, the patient is instructed to take 2 sennosides tablets 3 times daily. Once the patient finds the dosage level that allows him or her to have a BM that is comfortable to pass at least every 2 to 3 days, that dosing is maintained. If diarrhea occurs, the patient should stop taking the laxative until an adequate BM is formed and then restart the sennosides tablets at a lower dosage level. If the patient has gone more than 3 days without a BM, he or she is urged to contact the physician.3

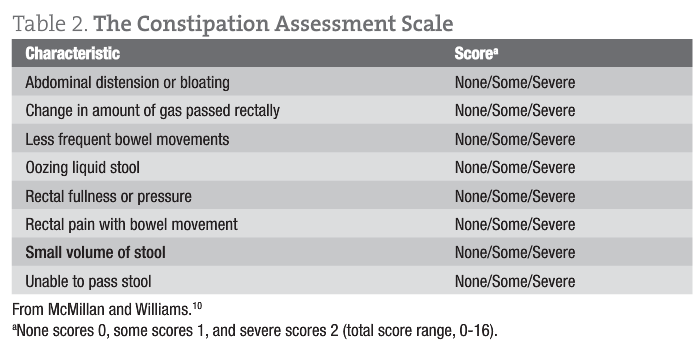

Until a routine is established with the pain medications and laxatives, it is very helpful to have the patient track the frequency of his or her BMs. The Constipation Assessment Scale (Table 2) was developed to help patients self-report and to help caregivers assess the effectiveness of treatment.4 The scale comprises 8 characteristics that are considered universally related to constipation on the basis of the literature. Each characteristic is rated on a 3-point scale (no problem, some problem, or severe problem), scored as 0, 1, or 2. The scores are summed to render a range between 0 (no constipation) and 16 (the most severe constipation).

The National Institutes of Health Pain Consortium11 has addressed the reliability of the Constipation Assessment Scale:

The CAS [Constipation Assessment Scale] was tested for construct validity and sensitivity by comparison of results obtained on 32 normal volunteers and 32 patients receiving either morphine or vinca alkaloid chemotherapy (t = 6.32, p < 0.0001). Reliability (r = 0.98) and internal consistency (alpha = 0.70) were also satisfactory. The scale was able to distinguish between more and less severely constipated groups (on the assumption that the chemotherapy patients were less constipated than those receiving morphine) (t = 2.54, p < 0.01). Completion time averaged about two minutes.

In addition to any over-the-counter products that patients are using to prevent or treat opioid-induced constipation, we should always emphasize the basics of good bowel health. The first thing I suggest is putting patients on a regular daily routine to increase their bowel tone.

Every morning, before getting out of bed, they are instructed to gently massage their abdomen in a clockwise motion. Stimulation of the colon through massage increases colonic motility, while massaging in a clockwise motion encourages the normal flow of stool toward the rectum.

After rising, the patient should drink at least 8 oz of warm (not tepid) water to stimulate the gastrocolic reflex. This reflex, resulting from the distension of the stomach, signals the terminal ileum to empty its contents into the cecum, which then stimulates mass peristaltic movements.

A gentle walk for 15 to 20 minutes will also stimulate the bowel. This should be done after each meal.

If taking a stool softener, patients should increase their fluid intake to approximately 8 to 12 servings per day. This could include filtered water, herbal teas, juices, and thin soups. Warm to hot liquids have the added benefit of increasing peristalsis. Coffee, caffeinated teas, and alcohol have a diuretic effect and should be avoided. Dietary fiber can be increased with the addition of whole grains, cereals, oat bran, and fresh fruits and vegetables. Beans, lentils, peas, nuts, and seeds (especially flaxseeds) are also good dietary additions. Good sources of fiber are pectin-containing foods such as apples, carrots, beets, bananas, cabbage, citrus fruits, dried peas, and okra. Ideally, the patient will be consuming 20 to 30 g of dietary fiber daily.2,3 Regular exercise, as much as the patient can comfortably tolerate, will assist to promote normal motility of the bowel.2

Other naturopathic treatments that will help with constipation include the addition of supplemental magnesium (at a dosage of ≥500 mg, to bowel tolerance). Probiotics should also be included, especially for patients who have had recent surgery, with accompanying antibiotics. I would suggest starting slowly and titrating up over several days to prevent any additional gas or bloating that introducing the new flora might cause. Finding the homeopathic simillimum for the constipation symptoms can boost the vital force to deal with the symptoms of OBD. Remedies to consider are Alumina, Bryonia, Hydrastis, Nux vomica, Opium, Silicea, and Sulphur.12

Utilizing the healing power of water can have a beneficial influence in treating constipation. Patients can perform home hydrotherapy by ending their morning shower with a spray of cool water (working up to cold) over the abdomen to reflexively increase blood and lymph circulation to the intestines. Prolonged cold to the skin of the abdomen causes increased intestinal blood flow, intestinal motility, and acid secretion to the stomach.13 Ideally, the patient could take a series of constitutional hydrotherapy treatments to stimulate the entire digestive tract. In addition to alternating hot and cold to the chest and abdomen, sine wave is used to augment nerve action to the abdominal organs, improving digestion, absorption, and elimination.

Considering the prevalence of opioid-based medications used for treating pain, both for short-term and long-term care, and the high risk for OBD in patients taking these medications, physicians need to be aware of proper protocols for managing OBD before it becomes a serious problem for their patients. A protocol that aims at preventing OBD starts with evaluating patients for risk of opiate-induced constipation before initiating opiate medication use. With the initiation of opioids, patients are urged to also begin prophylactic laxative use. Naturopathic therapies and lifestyle counseling will further assist patients in maintaining normal or near-normal bowel functioning when taking pain medications.

Gaia Mather, ND was a 1990 graduate from the National College of Natural Medicine and is now a full-time faculty member. She is dedicated to helping preserve those modalities that are unique to Naturopathic Medicine. Dr. Mather is the Clinical Hydrotherapy Administrator and coordinates the Hydrotherapy program at NCNM. Aside from teaching Hydrotherapy Lecture and Lab courses, she also teaches Palpation, Bodywork, and Colonic Hydrotherapy. When not teaching, she enjoys using homeopathy and flower essences to help people and their pets find a happy balance.

Gaia Mather, ND was a 1990 graduate from the National College of Natural Medicine and is now a full-time faculty member. She is dedicated to helping preserve those modalities that are unique to Naturopathic Medicine. Dr. Mather is the Clinical Hydrotherapy Administrator and coordinates the Hydrotherapy program at NCNM. Aside from teaching Hydrotherapy Lecture and Lab courses, she also teaches Palpation, Bodywork, and Colonic Hydrotherapy. When not teaching, she enjoys using homeopathy and flower essences to help people and their pets find a happy balance.

References

- Goodheart CR, Leavitt SB. Managing opioid-induced constipation in ambulatory-care patients. August 2006. Pain Treatment Topics. http://pain-topics.org/pdf/Managing_Opioid-Induced_Constipation.pdf. Accessed November 19, 2012.

- Zagaria ME. Preemptive treatment of constipation when opioids are initiated. US Pharm. 2012;37(1):21-24. http://www.uspharmacist.com/content/d/senior_care/c/32011/. Accessed November 19, 2012.

- BC Cancer Agency. Symptom management guidelines: constipation. http://www.bccancer.bc.ca/HPI/Nursing/Education/breastcancer/symptommgt/Symptom+Management+Guidelines.htm. Accessed November 19, 2012.

- McMillan SC. Accessing and managing opiate-induced constipation in adults with cancer. Cancer Control. 2004;11(3)(suppl):3-9.

- Bell TJ, Panchal SJ, Miaskowski C, Bolge SC, Milanova T, Williamson R. The prevalence, severity, and impact of opioid-induced bowel dysfunction: results of a US and European patient survey (PROBE 1). Pain Med. 2009;10(1):35-42.

- Panchal SJ, Muller-Schwefe P, Wurzelmann JI. Opioid-induced bowel dysfunction: prevalence, pathophysiology and burden. Int J Clin Pract. 2007;61(7):1181-1187.

- Pappagallo M. Incidence, prevalence, and management of opioid bowel dysfunction. Am J Surg. 2001;182(5A)(suppl):11S-18S.

- Thomas JR, Cooney GA, Slatkin NE. Palliative care and pain: new strategies for managing opioid bowel dysfunction. J Palliat Med. 2008;11(suppl 1):S1-S19.

- BC Cancer Agency. Outpatient bowel protocol summary. http://www.bccancer.bc.ca/NR/rdonlyres/A0CC1998-13DE-4766-A572-2B34703EE4E5/53181/BCCABowelProtocol.pdf. Accessed November 19, 2012.

- McMillan SC, Williams FA. Validity and reliability of the Constipation Assessment Scale. Cancer Nurs. 1989;12:183-188.

- National Institutes of Health Pain Consortium. The Constipation Assessment Scale. http://painconsortium.nih.gov/symptomresearch/chapter_3/sec5/cnss5pop_cas.htm. Accessed November 19, 2012.

- Gibson DM. First Aid Homeopathy. 12th ed. Luton, England: British Homeopathic Association; 1986:40-41.

- Thrash AM, Thrash CL. Home Remedies: Hydrotherapy, Massage, Charcoal and Other Simple Treatments. Seale, AL: NewLife Style Books; 2005.