Vis Medicatrix Naturae

Matthew Strickland, ND

Abstract

Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) is increasingly recognized as both an underdiagnosed condition and a contributor to irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). This case study describes a 19-year-old female who developed persistent gastrointestinal symptoms following international travel. Despite a diagnosis of post-infectious IBS and conventional probiotic and fiber interventions, her symptoms of constipation, gas, bloating, abdominal pain, and weight loss persisted. A lactulose breath test confirmed SIBO, and treatment with targeted botanical antimicrobials led to marked improvement, followed by complete resolution after a second herbal protocol containing wormwood, black walnut, pomegranate, and other extracts. Probiotic therapy supported sustained remission. This case highlights the overlap between SIBO and IBS, the importance of considering infectious origins, and the efficacy of botanical medicine as a safe and effective therapeutic alternative to antibiotics in SIBO management.

Introduction

Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth, also known as SIBO, is an underdiagnosed condition of overgrowth of bacteria in the small intestine.1 Normally, the small intestine hosts a relatively small number of bacteria – around 1000 to 10 000 per mL of content. For comparison, further down the digestive tract, in the colon, there are around 100 trillion bacteria per mL of content.2 The natural motility of the small intestine and the low pH of the stomach acid combine to help keep the small intestine relatively free of bacteria.1

When the number of bacteria in the small intestine becomes excessive, a variety of non-specific symptoms can result including bloating, abdominal pain and distension, diarrhea, constipation, fatigue, and weight loss.1

These symptoms overlap with Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS).1 Furthermore, there is evidence that, in patients diagnosed with IBS who also have SIBO, successful treatment of the SIBO can cause resolution of both conditions: In a study of 202 patients with IBS, the vast majority (78%) tested positive for SIBO.3 And of the subjects for whom treatment to clear the overgrowth was successful, 48% no longer met the diagnostic criteria for IBS.

The following case study is similar. The presenting patient had a prior diagnosis of IBS, and also tested positive for SIBO. Treatment for the SIBO led to resolution of all symptoms and of the IBS.

Patient Presentation

A 19-year-old female presented to my office with digestive disturbance of 6 months’ duration. The symptoms started during a field trip to the Middle East during the previous summer. Her first symptom was diarrhea and was shared by some of her colleagues. Their symptoms resolved by the end of the trip, but hers continued. After returning to America, her symptoms partially resolved but worsened by the October following her field trip. She presented to a gastroenterologist and was given a single Ova & Parasite (O&P) microscopy test, which was negative. A colonoscopy was performed, which was within normal limits, and she was subsequently diagnosed with post-infectious IBS. She was given a proprietary probiotic of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG, and then a proprietary probiotic of Saccharomyces boulardii, to take along with psyllium husk wafers, but none of these agents resolved her symptoms.

At the time of her presentation to my office, her symptoms included constipation, excessive gas and borborygmus, abdominal pain, and weight loss. She described having occasional unproductive bowel movements, where only mucus and excessive amounts of gas would be passed.

A SIBO lactulose home breath-test was ordered from a commercial laboratory, with instructions to follow up in 3 weeks.

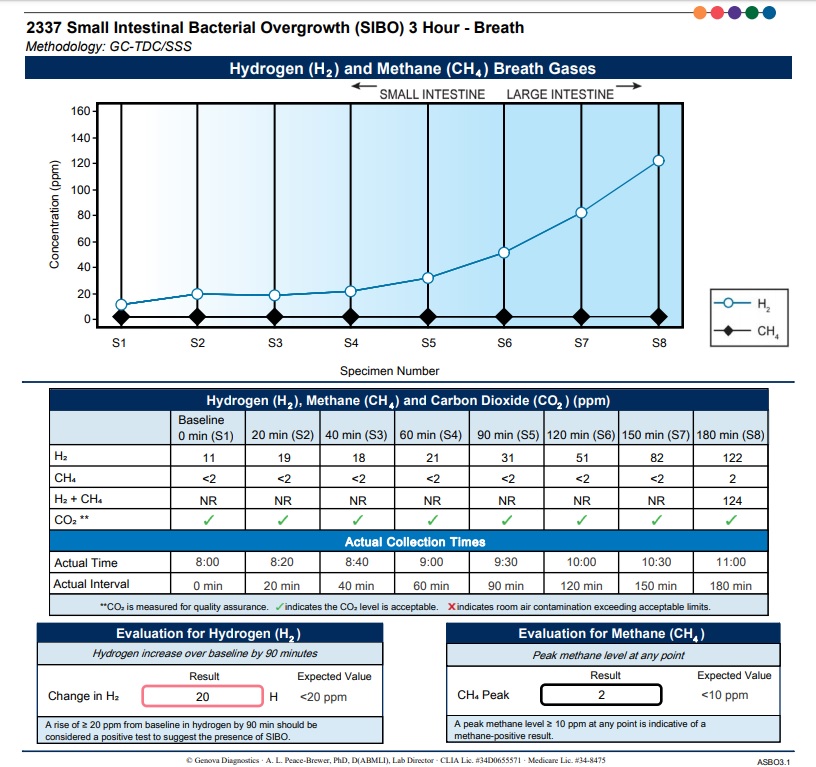

A breath test is the easiest was to diagnose SIBO.1,4 The human body is incapable of producing hydrogen (H2) or methane (CH4) gas on its own. Bacteria break down carbohydrates as part of the digestive process, producing a number of byproducts as a result, including these gases. The SIBO breath test quantifies the H2 and CH4 production in the small intestine at different time-points, and provides for SIBO diagnosis based on defined criteria.4

For the test, a patient takes an oral bolus dose of lactulose or another specific sugar, and breathes into test collection bags at regular time intervals, usually every 20 minutes. These samples are collected and then analyzed for their gas contents. A rise in H2 of >20 ppm from baseline over the first 90 minutes of collection, or CH4 levels >10 ppm at any time during the 90 minutes is considered diagnostic of SIBO.4

Follow-up Visits

First Follow-up (3 weeks after initial consultation)

The breath-testing showed a rise in H2 levels of 20 ppm over the first 90 minutes, just meeting the diagnostic criteria for SIBO. Since her previous visit, her symptoms had alternated between diarrhea and constipation. She was also having bad gas and bloating that would start anywhere from immediately after eating to up to 20 minutes later.

Figure 1. Breath Test Results

Her treatment plan consisted of 2 herbal supplements that have been studied specifically for the treatment of SIBO – one is a proprietary blend of thyme, oregano oil, and herbal extracts; and the other is a proprietary blend of berberine, Oregon grape, and other herbal extracts. The dosage for the first product was 1 softgel 3 times per day, and the dosage for the second product was 2 tablets 2 times per day, both to be taken with meals. The effects of these formulations were shown in a clinical study to be as or more effective than rifaximin, the medical standard of care for SIBO.5

In addition, I recommended she take a total of 3 billion CFUs of the probiotic Lactobacillus sporogenes at bedtime.

Second Follow-up (5 weeks later)

At the second follow-up visit – her first since reviewing the SIBO testing and starting the treatment plan – the patient reported a 50% improvement in digestion. She had complied with all treatment recommendations.

She was now having a regular bowel movement every morning; however, she was still passing some mucus, albeit less than before. She also reported less borborygmus and gas. Physical exam revealed excessive bowel sounds in all 4 quadrants.

It was clear that the herbal protocol had improved her symptoms, but there was still room for more improvement.

My recommendation was to stop the 2 herbal products, continue with the probiotic, and start taking a different herbal antimicrobial. This new proprietary product is an alcohol-based tincture containing extracts of sweet wormwood (Artemisia annua), black walnut hulls (Juglans nigra), pomegranate arils (Punica granatum), coptis root (Coptis chinensis), wormwood (Artemisia absinthium), clove buds (Syzgium aromaticum), gentian root (Gentiana lutea), and ginger (Zingiber officinale).

The first time I used this product was to clear a Cryptosporidium infection in a young man who had been misdiagnosed with inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn’s). It worked wonderfully, and I’ve since used it successfully for many different gastrointestinal conditions with an infectious – or suspected infectious – etiology or with an infectious contribution to presenting symptoms. The herbs included in the tincture combine to provide broad-spectrum antibacterial6-8 and antiparasitic activity.9,10

I instructed her to take an increasing amount between meals: 1 dropperful for the first week, 2 dropperfuls for the next week, and 3 dropperfuls split between meals for the subsequent 3 weeks until follow-up.

Third Follow-up (5 weeks later)

At the third follow-up visit – the first since starting the wormwood/black walnut formula – the patient reported a complete resolution of symptoms. Her digestion was “much better” than at the last visit. She was having no more gas or bloating after meals, no mucus in her bowel movements, and no borborygmus. She was having a single well-formed bowel movement in the mornings, and only had a second bowel movement if she ate a lot of fiber at a meal. She also reported weight gain. Her physical exam revealed normal bowel sounds in all 4 quadrants.

My recommendation was to discontinue the tincture and to stay on the probiotic for at least another 6 months. I encouraged her to take the tincture with her when traveling, to use as needed.

Discussion

When approaching a case, exploring the circumstances around the onset of symptoms, and with as much detail as possible, is crucial. This patient had no history of digestive issues until her travel to the Middle East, and her colleagues all reported digestive issues, although their symptoms resolved. This pointed to an infectious etiology. A single-sample O&P test was performed by her gastroenterologist. Evidence suggests that a 3-sample collection (at different points in time) is more sensitive than a single collection, thus would have been a preferred way to test.11 A culture-based stool test or a newer PCR-based stool test would have also provided more information. If the SIBO test hadn’t been positive, that would have been my next step in working through the infectious differential diagnosis.

This case study supports the evidence of overlap between SIBO and IBS, as well as the efficacy of botanicals in resolving SIBO. Breath testing for SIBO is relatively inexpensive, with limited side effects, and should be considered in patients with IBS or those presenting with IBS-like symptoms.

References:

Dukowicz AC, Lacy BE, Levine GM. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: a comprehensive review. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2007;3(2):112-122.

Sender R, Fuchs S, Milo R. Revised Estimates for the Number of Human and Bacteria Cells in the Body. PLoS Biol. 2016;14(8):e1002533.

Pimentel M, Chow EJ, Lin HC. Eradication of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95(12):3503-3506.

Rezaie A, Buresi M, Lembo A, et al. Hydrogen and Methane-Based Breath Testing in Gastrointestinal Disorders: The North American Consensus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112(5):775-784.

Chedid V, Dhalla S, Clarke JO, et al. Herbal therapy is equivalent to rifaximin for the treatment of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. Glob Adv Health Med. 2014;3(3):16-24.

Pagliarulo C, De Vito V, Picariello G, et al. Inhibitory effect of pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) polyphenol extracts on the bacterial growth and survival of clinical isolates of pathogenic Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. Food Chem. 2016;190:824-831.

Wang J, Wang L, Lou GH, et al. Coptidis Rhizoma: a comprehensive review of its traditional uses, botany, phytochemistry, pharmacology and toxicology. Pharm Biol. 2019;57(1):193-225.

Ajiboye TO, Mohammed AO, Bello SA, et al. Antibacterial activity of Syzygium aromaticum seed: Studies on oxidative stress biomarkers and membrane permeability. Microb Pathog. 2016;95:208-215.

Munyangi J, Cornet-Vernet L, Idumbo M, et al. Effect of Artemisia annua and Artemisia afra tea infusions on schistosomiasis in a large clinical trial. Phytomedicine. 2018;51:233-240.

Ramazani A, Sardari S, Zakeri S, Vaziri B. In vitro antiplasmodial and phytochemical study of five Artemisia species from Iran and in vivo activity of two species. Parasitol Res. 2010;107(3):593-599.

Marti H, Koella JC. Multiple stool examinations for ova and parasites and rate of false-negative results. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31(11):3044-3045.

Matthew Strickland, ND, is a leader in integrative, functional, and naturopathic medicine. He treats patients at a distance, as well as in-person at his clinic, Southeastern Integrative Health and Wellness, in Durham, NC. Dr Strickland is currently serving as Vice President of the North Carolina Association of Naturopathic Medicine.