Chris Habib, BSc, ND

The Royal Society of Canada has described addiction as a strongly recognized pattern of behavior characterized by the repeated self-administration of a drug in quantities that recurrently produce reinforcing psychoactive effects, and one which includes difficulty with voluntary long-term discontinuation of use, even when motivated to discontinue.1 The use of tobacco products containing nicotine is well established to meet these criteria. The question now revolves around how smoking exposure causes addictive behaviors.

Why is Nicotine Addictive?

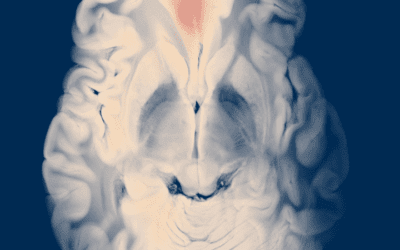

Nicotine is the key component of cigarette smoke implicated in addiction. Nicotine’s pharmacokinetics increases its ability to enforce dependence via rapid distribution to the brain within 10 seconds of inhalation.2 The primary aspect of nicotine’s addictive potential comes from its ability to activate the reward pathways in the brain.2

The reward system in the brain consists of a group of neurons involved in regulation of behavior through pleasurable effects. This system consists of the mesolimbic pathway – a major neurochemical pathway that runs from the ventral tegmental area to the nucleus accumbens and which plays a central role in the neurobiology of addiction.3 Nicotine exerts effects on several neurotransmitters systems, such as acetylcholine, dopamine, noradrenaline, serotonin, opioid, glutamate, and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA).4 However, the key neurotransmitter implicated in the mediation of desire for continued consumption of addictive substances is dopamine. Tobacco produces elevations of dopamine in the limbic system (consisting of the hypothalamus, hippocampus, and amygdala), which is associated with motivation, learning, memory, and emotion.4 In the ventral tegmental area of the brain (associated with cognition, motivation, orgasm, drug addiction, and intense emotions), nicotine binds to nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) on both GABAnergic and glutamate neurons that stimulate dopaminergic neurons, as well as acting directly on nAChRs located on the dopamine neurons themselves.4 Overall, these innervations result in the release of dopamine.

This ability to elevate dopamine levels is the fundamental principle uniting addictive drugs.5 Increased stimulation of dopaminergic neurons, especially those in the reward system of the brain, is associated with increased incentive learning or reinforcement of behavior such as smoking.3 When dopaminergic neurons in the mesolimbic pathways in rats are lesioned, self-administration of nicotine is shown to decrease, thus illustrating the importance of this pathway in addiction.4 Thus, nicotine’s ability to enter the brain, virtually simultaneously with inhalation, and its ability to interact with neurons in the reward centers of the brain to increase dopamine levels – resulting in a reinforcement of behavior – helps to explain why this drug results in addiction.

Outcomes in Health and Performance

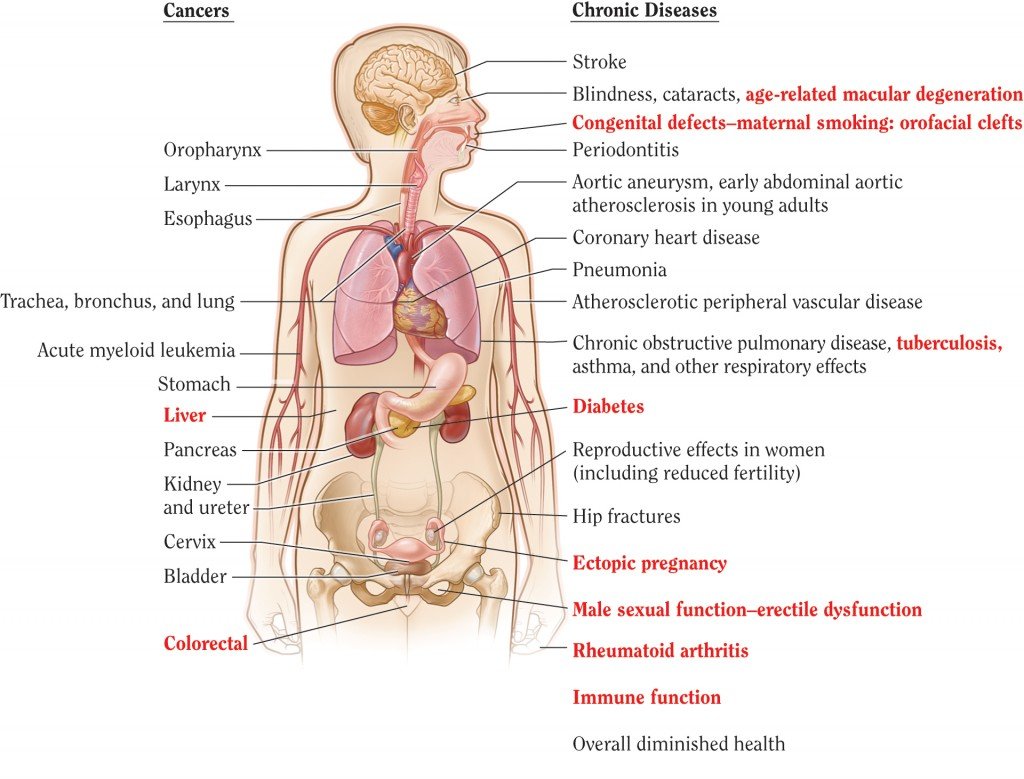

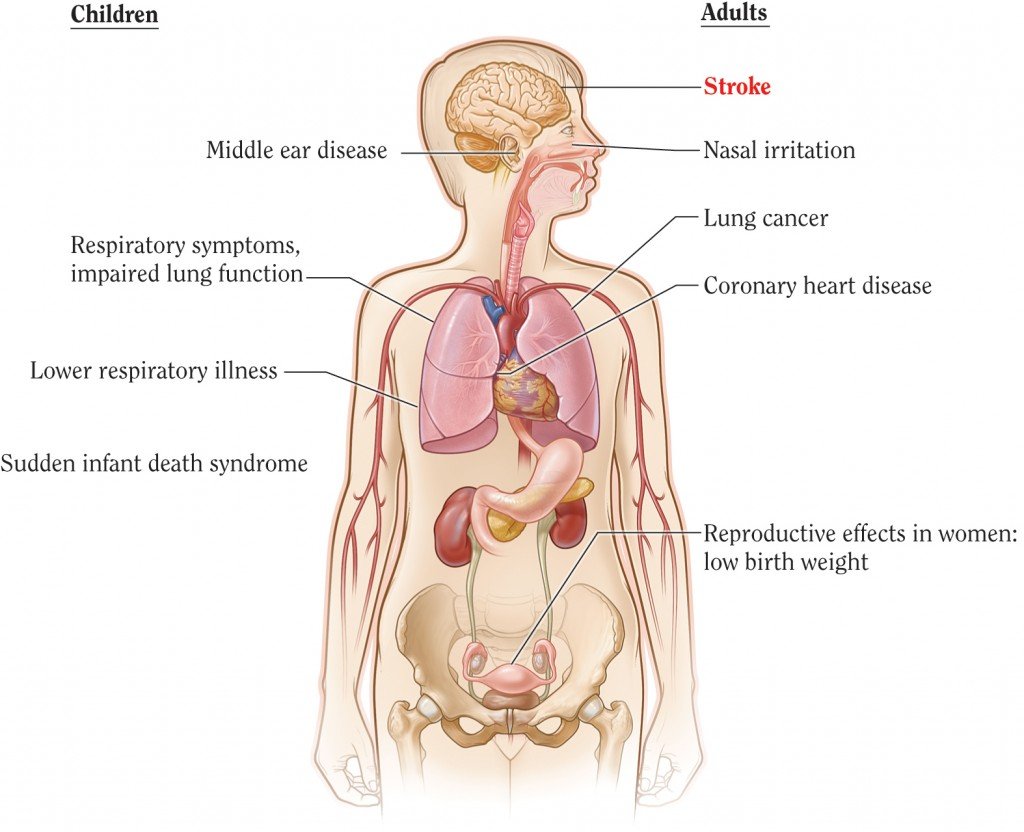

The sale of tobacco may have declined over the past decade, but the implication it has on health and performance has increased over the years. Premature death due to smoking is higher today than in was 10 years ago, and over 16 million people in the United States, alone, currently live with disease caused by tobacco use.6,7 Ongoing research and awareness over the past 50 years has highlighted more death, disease, and health risks caused by tobacco use than what was known before. A 2014 article written by the US Department of Health outlines in a 50-year progress report the health consequences of smoking. The article highlights the new health consequences of smoking (Figure 1) and of secondhand smoke (Figure 2) that were once assumed to pertain to respiratory concerns alone. In fact, nearly every organ within the body can be impacted by cigarette smoke exposure, proving that no amount of exposure is risk-free.7

Figure 1. Health Consequences Linked to Smoking

(Source: US Department of Health and Human Services. Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta (GA): US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2014.)

Figure 2. Health Consequences Linked to Secondhand Smoke Exposure

(Source: US Department of Health and Human Services. Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta (GA): US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2014.)

Note: The condition in red is a new disease that has been causally linked to smoking in this report.

So what is it about cigarettes that impact our health to such a great magnitude? The answer, according to David B. Abrams, a professor at the John Hopkins School of Public Health, is tobacco and combustion. When you light up a cigarette, the combustion that occurs with the ingredients inside forms an inhalant that takes only seconds to reach the brain, the bloodstream, and your cells. From there, the biggest risk they pose is damage of DNA.8 This type of damage in the lungs accounts for 85% of all lung cancer cases, and continues to be the leading cause of death from cancer in Canada.9 New evidence has also highlighted that the risk of developing liver and colorectal cancers has a strong causal relationship to tobacco use.7

The damage extends beyond our DNA. The chemical inhalants from tobacco also damage blood cells and blood vessels, increasing the risk of atherosclerosis, coronary heart disease, heart attacks, heart failure, and arrhythmias.10 Certain chemicals, such as cadmium, have even been shown to weaken the immune defense system within the body and render our detoxification enzymes useless. This leaves smokers even more vulnerable to the ongoing damage that years of smoking can have on the body. New disease developments are continuously unfolding with the study of tobacco use, with light being shed on the risk of diabetes, immune suppression, inflammation, arthritis, and infertility (Figures 1 and 2).

So, with all the literature put forward not to smoke, will smoking cessation be able to reverse any of the damage? Or is it permanent? According to the American Lung association, that can depend. For example, it depends on how long a person was smoking, and how much damage has been done so far.11 “Pack years” are measured by the number of packs smoked in a day, multiplied by the total number of years smoked. Obviously someone who has been smoking for 50 years has developed a larger risk of smoking-related cancers and disease than that of a 2-year smoker. When people do quit, their breathing will get better, they will cough less, and their immune response will improve. A study done on young men in military base training found that there was a significant overall physical aerobic improvement, from the initial running time of men who smoked, to their final time after 3 months of smoking cessation, independent of other health characteristics.12 This study warrants more literature to motivate young adults to quit smoking and to understand that it may not be too late to improve health and performance from years of addictive habits.

“[When it comes to cancer], we calculate the risk for lung cancer to return to that of a non-smoker with 10-15 years after smoking cessation,” says Norman Edelman, Chief Medical Officer of the American Lung Association.11 The damage to DNA, lung function, blood vessels and tissues, however, can be difficult to reverse. Lungs cannot grow new walls or blood vessels, so that can be permanent.11 Chronic inflammation can be reversed, especially with the adjunct care from naturopathic medicine, but any scarring left from the damage will be hard to fix.

Smoking Impacts Fertility

Cigarette smoke can alter one’s ability not only to conceive, but also to carry a fetus to term. Smoking has been shown to have significant detrimental effects on many of the organs in the body, including the reproductive system. It has the ability to affect fertility through various modes of exposure: first-hand, second-hand, and in-utero. Smoking can delay a couple’s ability to conceive naturally for more than a year.13 A study published by Reproductive Endocrinology looked into the fertility of all couples that were expected to deliver within a 9-month period, to determine whether first-hand and/or second-hand smoke delayed their ability to conceive.13 The study showed the largest decline in fertility among women who smoked and were exposed to second-hand smoke. It also found that male smoking was independently linked to infertility, even if they did not expose their partners to secondhand smoke. They found that women who smoked had a decreased ability to conceive both naturally (by 20%) and through IVF (by 33%).14 However, other investigations have noted up to a 60% increase in infertility among women who smoke.15 The study also found little evidence noting a difference in fertility between those who smoked 1 cigarette per day and those who smoked up to 14, illustrating that all exposure has negative consequences for fertility.14

Smoking has been shown to affect fertility through a decrease in ovarian reserve and anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) and an increase in irregular menses and ovarian insufficiency.12 AMH is only produced in small, growing ovarian follicles, and thus blood levels can be an indicator of the number of developing follicles. This hormonal decrease may provide insight into the reasons why female smokers have a decreased likelihood of undergoing successful IVF treatment.16 Decreases in AMH are also seen in women approaching menopause, and studies have found that women who smoke tend to experience menopause 1 to 1.5 years earlier than non-smokers.15 Smoking not only impacts one’s ability to conceive, but also impacts outcomes of pregnancy. It is associated with an increased risk of miscarriage, increases in bacterial vaginosis (which is independently linked with an increased miscarriage risk), preterm labor, and delivery of infants with low-birth weights.15

In males, cigarette smoking can result in several alterations in the functionality of reproductive cells and an increase in the number of abnormal cells. It has been shown to decrease seminal sperm counts, increase spermatozoal DNA fragmentation, and decrease sperm motility.14 Not only can current smoking in males affect fertility, but it has also been demonstrated that in-utero exposure to maternal smoking can have significant long-term implications on male fertility.17 Men who were exposed in utero demonstrated a reduction in sperm concentration, total sperm count, motility, normal morphology, and testis size.17 Moreover, these alterations in semen quantity, quality, and testicular size were not noted in those exposed in childhood, only in utero.17 Thus it is of significant importance to advise female smokers that smoking may not only have a detrimental effect on their personal fertility but also a generational effect on the future fertility of their sons.

There is hope for the fertility of smokers through cessation. It has been demonstrated that the adverse effects of smoking on female fertility is largely reversible. This is notable by comparing the conception rates of ex-smokers with never-smokers, which is fundamentally comparable, and also through noting that IVF rates are not reduced in ex-smokers.14 However, there is a permanent detrimental effect of cigarette smoking on ovarian follicular depletion, as seen via the reduction of AMH.14 Improvements in male fertility are also seen post-smoking cessation. Semen analysis of men 3 months after quitting smoking showed an improvement in sperm concentration and sperm vitality. However, no changes were observed in sperm morphology and DNA fragmentation.18 Therefore, it would be most beneficial to educate both men and women about the harmful effects of cigarette smoke on their fertility both in the short term and long term.

Avoiding Triggers

Many factors outside of nicotine cravings can trigger the desire to smoke. These factors are usually reminders of daily situations in which the smoker used to smoke. Triggers include: moods, places, feelings, people, and daily activities, for example being around other smokers, stress, driving or being in a car, enjoying a coffee, tea, or meal, drinking alcohol, boredom, and certain times of the day (especially the start of the day). Recognizing one’s triggers is the first step to staying in control because the smoker can then try to avoid the triggers or try to keep the mind busy or distracted when avoidance is not possible. For example, if one’s main trigger is being around other smokers, strategies would include limiting contact with smokers, excusing oneself when in a group where smoking is taking place, and having a smoke-free home.19 Specific times of day, especially right after waking (when nicotine levels are lowest), can be a trigger for smokers. Strategies for avoiding this trigger can include having a different morning wake-up routine, using deep breathing to divert attention, ensuring that there are no cigarettes available, drinking water, and keeping busy, especially for the first hour or 2.19 Stress is another common trigger for most smokers. Recognizing the causes and signs of stress is important in order to develop new coping strategies, such as relaxation techniques (eg, meditation, yoga, progressive muscle relaxation, and allowing for time away from stressful environments).19

Some smokers get accustomed to smoking while driving, whether it is to relieve stress, to stay alert, or to pass the time. For short trips, taking an alternate route can help to change the routine, also keeping snacks in the car, and cleaning the car thoroughly to reduce the smell of tobacco. For longer trips, planning frequent rest stops for stretches, water, and fresh fruits can help to maintain alertness, as well as curb the desire to smoker.19 Smokers can also associate smoking with drinking coffee/tea or having a good meal. Concentrating on the aromas and taste of the beverage or meal can shift the focus of the brain. Distraction techniques are useful here by keeping the hands busy while drinking a beverage, or washing dishes by hand after eating. Brushing teeth or using mouthwash after meals can help to eliminate the tastes that trigger cravings.19

Acupuncture for Smoking Cessation

Acupressure and acupuncture have been used as techniques to assist with smoking cessation. The National Acupuncture and Detoxification Association (NADA) protocol, in particular, is the most universally recognized intervention for the treatment of addictions.20 This protocol includes a group of 5 points consisting of: Sympathetic, Shen Men, Kidney, Liver, and Lung. Recent studies (within 10 years) are conflicting with regards to the efficacy of acupressure and acupuncture for smoking cessation. One study demonstrated a positive association between acupressure and abstinence rates; however, no placebo arm was used.21 Two studies reported higher rates of abstinence using auriculotherapy and auricular acupuncture.21, 22 However, these results were not significant. Other studies reported no difference in the rate of cessation,23,24 although one of these studies showed a slight decrease in tobacco consumption in the treatment group.24 Although studies are conflicting, more research should be done with improved study designs and protocols. Research shows that both acupressure and acupuncture are tolerated well by patients, and with no side effects.

Note: Coauthors of this article include CCNM graduates Emily Rotella, Maria Wong, Natalia Ytsma, and Sara Mohammed.

Chris Habib, BSc, ND, is an evidence-based naturopathic doctor with over a decade of education in healthcare. He is the clinic director of the multi-disciplinary clinic Mahaya Forest Hill and the Sales Director of the herbal company Perfect Herbs. Chris is also involved in teaching, research, and publishing. He is a clinic supervisor at the naturopathic college and teaches the board exam preparation course. He is also Associate Editor for the Journal of Restorative Medicine and Naturopathic Currents Magazine.

References:

- Kalant H, Clarke P, Corrigall W, et al. Tobacco, nicotine, and addiction: a committee report prepared at the request of the Royal Society of Canada. Ottawa, Ontario: Royal Society of Canada;1989.

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. Is Nicotine Addictive? Updated July 2012. Available at: http://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/research-reports/tobacco/nicotine-addictive. Accessed April 30, 2015.

- Balfour DJ, Wright AE, Benwell ME, Birrell CE. The putative role of extra-synaptic mesolimbic dopamine in the neurobiology of nicotine dependence. Behav Brain Res. 2000;113(1-2):73-83.

- Gamaleddin IH, Trigo JM, Gueye AB, et al. Role of the endogenous cannabinoid system in nicotine addiction: novel insights. Front Psychiatry. 2015;6:41.

- Sulzer D. How addictive drugs disrupt presynaptic dopamine neurotransmission. Neuron. 2011:69(4);628-649.

- Canadian Tobacco Use Monitoring Survey (CTUMS) 2012. Updated October 1, 2013. Health Canada Web site: http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/hc-ps/tobac-tabac/research-recherche/stat/ctums-esutc_2012-eng.php. Accessed April 20, 2015.

- S. Department of Health & Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General, 2014. Available at: http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/reports/50-years-of-progress/. Accessed April 20, 2015.

- Cancer Research UK. How smoking causes cancer. Last reviewed March 23, 2015. Available at: http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/causes-of-cancer/smoking-and-cancer/how-smoking-causes-cancer. Accessed April 21, 2015.

- Smoking and Your Body. Health effects of smoking. Updated November 1, 2011. Health Canada Web site. http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/hc-ps/tobac-tabac/body-corps/index-eng.php. Accessed April 25, 2015.

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. How Does Smoking Affect the Heart and Blood Vessels? Updated December 20, 2011. NHLBI Web site. http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/smo. Accessed April 25, 2015.

- Blue L. Is the Damage from Smoking Permanent? July 1, 2008. Time Magazine Web site. http://content.time.com/time/health/article/0,8599,1819144,00.html. Accessed April 28, 2015.

- Feinberg JH, Ryan MA, Johns M, et al. Smoking cessation and improvement in physical performance among young men. Mil Med. 2015;180(3):343-349.

- Alvarez S. Do some addictions interfere with fertility? Fertil Steril. 2015;103(1):22-26.

- Hull MG, North K, Taylor H, et al. Delayed conception and active and passive smoking. The Avon Longitudinal Study of Pregnancy and Childhood Study Team. Fertil Steril. 2000;74(4):725-733.

- Augood C, Duckitt K, Templeton AA. Smoking and female infertility: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod. 1998;13(6):1532-1539.

- Freour T, Masson D, Mirallie S, et al. Active smoking compromises IVF outcome and affects ovarian reserve. Reprod Biomed Online. 2008:16(1);96-102.

- Jensen TK, Jorgensen N, Punab M, et al. Association of in utero exposure to maternal smoking with reduced semen quality and testis size in adulthood: a cross-sectional study of 1,779 young men from the general population in 5 European countries. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159(1):49-58.

- Santos EP, Lopez-Costa S, Chenlo P, et al. Impact of spontaneous smoking cessation on sperm quality: case report. Andrologia. 2001;43(6):431-435.

- National Cancer Institute. How to Handle Withdrawal Symptoms and Triggers When You Decide to Quit Smoking. Reviewed October 29, 2010. NCI Web site. http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/causes-prevention/risk/tobacco/withdrawal-fact-sheet. Accessed April 25, 2015.

- The NADA Protocol. Acupuncture Today Web site. http://www.acupuncturetoday.com/abc/nadaprotocol.php. Accessed August 20, 2015.

- Breivogel B, Vuthaj B, Krumm B, et al. Photoelectric stimulation of defined ear points (Smokex-Pro method) as an aid for smoking cessation: a prospective observational 2-year study with 156 smokers in a primary care setting. Eur Addict Res. 2011;17(6):292-301.

- Wu TP,Chen FP, Liu JY, et al. A randomized controlled clinical trial of auricular acupuncture in smoking cessation. J Chin Med Assoc. 2007;70(8):331-338.

- Fritz DJ,Carney RM, Steinmeyer B, et al. The efficacy of auriculotherapy for smoking cessation: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Am Board Fam Med. 2013;26(1):61-70.

- Yeh ML,Chang CY, Chu NF, Chen HH. A six-week acupoint stimulation intervention for quitting smoking. Am J Chin Med. 2009;37(5):829-836.