Priessnitz’ Wet Sheet

Sussanna Czeranko, ND, BBE

Nature Cure Clinical Pearls

The healing method of nature consists, therefore, in the exercise of the power given to every organism, to eject out of it all materials inimical to it. – Charles Schieferdecker, 1844, p.135

Priessnitz, by his doings, has proved to the world two things: first, that the water cure is the most natural and best system of treatment; and second, that he is a man possessing a genius most remarkable. – Joel Shew, 1851, p.55

The wet sheet, this greatest of all remedial applications, is destined, the world over, to become a family word; and in connection with its use, the name of Priessnitz will be known so long as time shall last! – Joel Shew, 1851, vol IV, p.84

In last month’s article we learned of Vincent Priessnitz’s persistent and successful use of the “sweating blanket wrap and half baths” in treating patients harmed by the allopathic use of calomel. Allopathic medicine has a track record of using frequently harmful substances, such as mercury chloride, capable of “rendering the body incapable of producing the external symptom, by depriving it of its power of throwing out through the skin the noxious matter by which the disease has caused.” (Schieferdecker, 1844, p.31) Priessnitz, in his wisdom, recognized the need to rid the body of substances that were deleterious, but by means of natural therapies that would do no harm. This month we are going to explore the merits of one such treatment – the wet sheet.

There is an abundant literature from the mid-19th century which will make the modern naturopathic doctor marvel at the innovative brilliance of Vincent Priessnitz. Indeed, that literature indicates that the scope of hydrotherapy was decisively determined by this one man. The water applications that were popularized by late 19th-century hydrotherapists, such as Kneipp, Kuhne, Bilz, and Just, can be traced back to Priessnitz. His methodologies were adopted and adapted to meet the needs of those who followed in his footsteps. Among that literature are the writings of a young medical doctor, Dr Joel Shew (1816-1855), who studied with Priessnitz. Shew’s work is instrumental in detailing the importance and significance of the strikingly original work of Priessnitz.

Figure 1. Vincent Priessnitz

The story of Priessnitz at age 16 using wet bandages to heal after a traumatic accident resulting in broken ribs is often cited as his first foray into hydrotherapy. However, his first encounter with water was earlier, at the age of 13, when he sprained his wrist. Instinctively, Priessnitz placed his wrist under the flow of water from the water pump. “Finding that the water cooled the part, and assuaged the pain, but unable to keep it constantly there, it occurred to him to apply an umschlag or wet bandage.” (Shew, 1951, p.58) The wet bandage was his first “aha” moment to devise a steady cold-water application. His life as a healer using water was spurred on by his infinite curiosity about the many possibilities for water in healing. The effectiveness of the wet compress led to much experimentation by Priessnitz to expand the therapeutic applications of water. His accidental discovery that cold water could relieve pain encouraged him to apply a wet sheet to the whole body for a multitude of conditions.

His contributions to hydrotherapy did not end with the wet compress, but rather included an exhaustive list of therapies. When local chronic diseases failed to respond to the wet sheet bandage, Priessnitz conceived of the partial baths, which were local applications to head, eye, arm, pelvis, leg, and foot. He was the architect of the full-body wet sheet wrap, the douche or shower, the sponge or ablution, the cold plunge bath, and the shallow bath that would be the precursor to Adolf Just’s natural bath. He also invented the sweating blanket pack after “observing that perspiration frequently relieved pain, and was efficacious in many diseases, and unlike the vapor and hot baths, did not accelerate the circulation and debilitate the [patient].” (Shew, 1851, p.60) The dripping wet sheet was a later invention and used as a preparation for other and stronger water applications. (Shew, 1851, p.61)

Wet Sheet, or Leintuch

Shew was fastidious in documenting the work of Priessnitz. Although Shew himself lived a short 39 years, he left behind many books extolling Priessnitz’s accomplishments and contributions. Vincent Priessnitz is renowned for the invention of the “wet sheet packing,” or “wrap.” While Kneipp aspired to create the gush or douche, Priessnitz’s contribution to hydrotherapy included the use of the full-body wet sheet wrap. The wet sheet shines brilliantly in Shew’s eyes: “Of all his discoveries, this may be esteemed the most important, considered with reference to the extent and variety of diseases in which [the wet sheet] is employed, and would alone have embalmed his memory in the recollections of a grateful posterity.” (Shew, 1851, p.60)

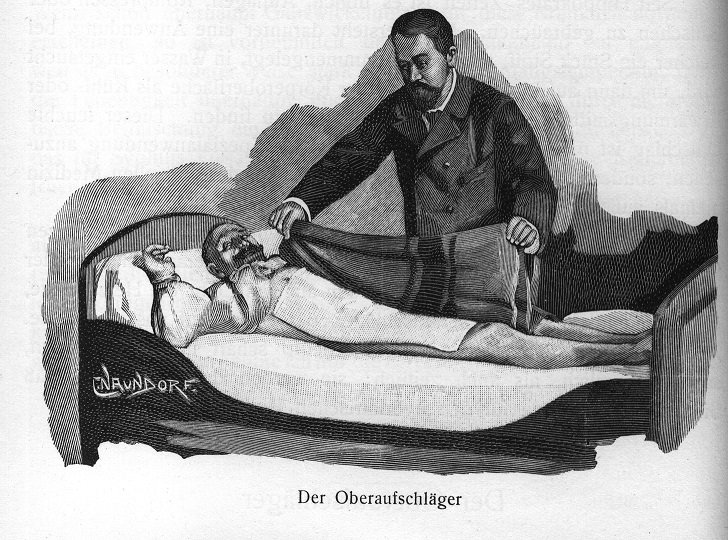

Figure 2. Blanket Wrap

Linen or Cotton Sheets?

A wet sheet consisted of either cotton or coarse linen, the latter holding more water. Linen was preferred, in fact, when the patient had a fever because “it was more cooling.” (Shew, 1851, vol IV, p.81) This wet sheet would be wrung out and placed on 1 or more large, thick woolen blankets. Anyone who has had a wet sheet experience will remember the shockingly-cold first contact with the wet sheet. The successful execution of the wet sheet, then, is speed and care. The patient is “quickly and snugly enveloped from neck to the feet, first with the wet sheet and then the blankets” (Shew, 1851, p.148), which prevent evaporation and chilliness. “If the patient has cold feet, bottles of warm water were placed beside the feet.” (Shew, 1851, vol IV, p.81) The packing is finished by placing on top of the patient a feather duvet or a blanket to retain warmth. The duration of the wet sheet application varied between 20 minutes and long enough for the patient to become warm. (Shew, 1851, p.148)

The wet sheet was generally applied during the day, but could also be used at night. Shew describes his experience of applying a wet sheet at night in winter with no heat in the room. He remarks, “I had a bad cold on going to rest, but in the morning it was all gone.” (Shew, 1851, vol IV, p.84)

Two Different Effects

Fever Reduction

Shew reports that the mechanism of action for the wet sheet had “two diametrically opposite effects, accordingly as it is used.” (Shew, 1851, p.148) If the wet sheet is used to reduce a fever, it would be removed and changed frequently, as soon as the patient becomes warm. The frequent changing lowers the fever slowly and gradually. If the fever continues high and burning, though, “two or three sheets at a time [are used for] the refrigerant action [to] be longer continued.” (Shew, 1851, vol IV, p.82) To aid in the fever reduction, Priessnitz would eliminate the use of blankets and just have wet sheets applied to the patient. However, at no time was chilliness permitted in the patient; in such cases, blankets and warm baths would remedy the chill.

Poultice Effect

Of note, Shew goes on, is that “if the patient remain[s] for half an hour, the most delicious sensation of warmth, and a gentle breathing perspiration are produced, while all pains and uneasiness are removed.” (Shew, 1851, p.148) The wet sheet essentially acts as a warm poultice that is incorporated in alleviating inflammation and pain. Shew describes the poultice effect that Priessnitz discovered in the wet bandage. “A moist cloth placed upon a part, covered with a dry one, to prevent evaporation (a cooling process) soon, from the warmth of the body, becomes soothing and warm: a sort of genial vapor bath is formed upon the part, which is neither more nor less than a poultice effect.” (Shew, 1851, vol IV, p.80)

Shew noted, “So delicious are the sensations caused by the wet sheet, persons are very apt to desire to remain in it too long.” (Shew, 1851, vol IV, p.82) The rule determining duration was to stay in the wet sheet until one becomes warm. Shew continues, “In some cases, 15 minutes are required, and in others, an hour or more.” The objective of a wet sheet was not to induce perspiration in the patient. Shew reinforces this point: “Sweating is, of itself, a debilitating process; the times for it are the exceptions, and not the rule.” (Shew, 1851, vol IV, p.82)

Complications could arise if the patient remained too long in a wet sheet, resulting for example in “headaches, giddiness and fullness of the head.” (Shew, 1851, vol IV, p.83) Those who lacked body heat, or were very weak, and got chilled as a result of the wet sheet were advised to stop and remove themselves. “Persons in such cases, should come from the sheet, while [still] feeling warm.” (Shew, 1851, vol IV, p.82)

Priessnitz’s early hydrotherapy practice depended upon the blanket sweating pack to induce copious perspiration and the elimination of bodily toxins. Towards the end of his life, Priessnitz had “discarded [the blanket sweating pack], as a general remedy, in favor of packing in the wet sheet.” (Shew, 1851, p.95) Priessnitz observed that “sweating is necessary, in order to eject the noxious matter.” (Schieferdecker, 1844, p.67) Discovering the wet sheet, Priessnitz felt that it was more efficient in removing foreign matter and toxins that did not necessarily result in “copious sweating.” It was noted, however, that after a wet sheet which sometimes did not elicit perspiration, the skin nevertheless would be lighter in color, softer, and more pliable. (Shew, 1851, vol IV, p.80)

Schieferdecker notes another undeniable property of water, specifically its “strong tendency to dissolve, which exercises a constant operation in destroying all organic life, by resolving it into its elementary parts.” (Schieferdecker, 1844, p.52) The wet sheet also expedited sweating and the discharge of impurities from the body. Schieferdecker (1844, p.88) reminds us that “by sweating and other evacuations much matter detrimental to health has been removed,” and we are reminded, as noted in last month’s article, that Priessnitz was adept in using the depurative properties of water to detoxify calomel patients of mercury toxicity.

The Healing Crisis

In any case, what indicated a successful water-cure treatment was the appearance of a crisis; in fact, patients longed for them. “It is said that at Gräefenberg it is really amusing to observe with what anxiety it is looked for by the patients.” (Shew, 1851, p.173) The first sign of a crisis indicated that the successful cure was nearing its end.

Shew defines the ushering in of a crisis as “a sense of uneasiness, a loss of sleep and appetite, an alternate change from heat and cold, and lastly by all the symptoms of fever, which is sometimes violent, but always of short duration, if properly attended to.” (Shew, 1851, p.174) At the termination of the crisis, evacuations from the abdomen included diarrhea, and vomiting would be also accompanied by skin eruptions such as boils, ulcers, and abscesses. These sought-after symptoms that indicated that healing was assured might seem alarming or counterintuitive to us. For such crisis to occur, it meant that the body had a surplus reserve or strength to transform the chronic disease into an acute one.

The crisis was not an easy process and patients needed much courage to face the symptoms brought on by the crisis. The image of the disease as the enemy and the crisis as the struggle was aptly described: “This struggle never comes before the organism has recovered considerable strength, and gained such a degree of power as to be able successfully to enter into the combat with the enemy.” (Schieferdecker, 1844, p.93)

Schieferdecker writes about “the crisis”: “The water cure changes the chronically suffering into an acute struggle, called crisis, and this being introduced, it heals the body surely and radically.” (Schieferdecker, 1844, p.88) He continues, “The effect of the crisis is, however, the casting out of the materials causing illness, by means of urine, excrements, sweating, or ulcers.” (Schieferdecker, 1844, p.90) In the treatment of the crisis, care was taken to insure that the crisis was not aggravated or provoked to overwhelm the patient.

In case the organism has called forth a violent fever to assist it in producing ulcers, the patient is repeatedly closely wrapped in linen cloths. By this measure the eruption, seated beneath the skin, is partially driven out, and the fever is partly alleviated. But when the critical symptoms appear in too great a number and in too violent a degree, and too many and too large ulcers are coming forth: then cold water must not be resorted to at all, because the crisis would be heightened, and nothing must be done, excepting ablutions (to keep the skin open) and besides this, sometimes a mild sweat. (Schieferdecker, 1844, p.90)

Shew describes the crisis as “a visible effort on the part of nature or the natural powers of the system, to rid it of some morbid matter or matters in it, or expelling them at some of the natural outlets of the [body], as the skin, bowels and kidneys.” (Shew, 1851, vol IV, p.109) Boils or skin eruptions, or diarrhea and other symptoms of crisis indicated that “Nature has set vigorously about doing her work … and treatment should now be expectant or watching.” (Shew, 1851, vol IV, p.113) He continues, “Nature is now doing her work well. Do not thwart her by undue interference. Let her go on.” (Shew, 1851, vol IV, p.113)

The old writings from Shew’s era celebrate the effectiveness of Priessnitz’ wet sheet. In next month’s issue, we will explore some of the diseases that Priessnitz treated using his enduring water cure therapies.

References:

Schieferdecker, C. C. (1844). Vincenz Priessnitz: The Wonderful Power of Water In Healing the Diseases of the Human Body. Philadelphia, PA: Schieferdecker self-published; pp. 140.

Shew, J. (1851). Hydropathy, or the Water-Cure. New York, NY: Fowlers and Wells Publishers; pp. 360.

Shew, J. (1851). The Water-Cure Manual, Volume IV. New York, NY: Fowlers and Wells Publishers; pp 282.

Image Copyright: <a href=’https://www.123rf.com/profile_styleuneed’>styleuneed / 123RF Stock Photo</a>

Sussanna Czeranko ND, BBE, incorporates “nature-cure” approaches to primary care by including balneotherapy, breathing therapy, and nutrition into her naturopathic practice. Dr Czeranko is a faculty member working as the Rare Books curator at NCNM and is currently compiling a 12-volume series based upon Benedict Lust’s journals, published early in the last century. Her published books include: Origins of Naturopathic Medicine; Philosophy of Naturopathic Medicine; Dietetics of Naturopathic Medicine; Principles of Naturopathic Medicine; Vaccination and Naturopathic Medicine; and Physical Culture in Naturopathic Medicine. Dr Czeranko is the founder of the Breathing Academy, a training institute for naturopaths to incorporate a scientific model of breathing therapy called Buteyko into their practice. She is also a founding board member of the International Congress of Naturopathic Medicine and a member of the International Society of Medical Hydrology.

Sussanna Czeranko ND, BBE, incorporates “nature-cure” approaches to primary care by including balneotherapy, breathing therapy, and nutrition into her naturopathic practice. Dr Czeranko is a faculty member working as the Rare Books curator at NCNM and is currently compiling a 12-volume series based upon Benedict Lust’s journals, published early in the last century. Her published books include: Origins of Naturopathic Medicine; Philosophy of Naturopathic Medicine; Dietetics of Naturopathic Medicine; Principles of Naturopathic Medicine; Vaccination and Naturopathic Medicine; and Physical Culture in Naturopathic Medicine. Dr Czeranko is the founder of the Breathing Academy, a training institute for naturopaths to incorporate a scientific model of breathing therapy called Buteyko into their practice. She is also a founding board member of the International Congress of Naturopathic Medicine and a member of the International Society of Medical Hydrology.