Student Scholarship – 1st Place Case Study

Mark Iwanicki

Leslie Fuller, ND

Paroxysmal dyskinesias constitute a rare group of movement disorders affecting both adults and children. Paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesia (PKD) is characterized by episodic choreoathetosis, dystonia, or both, usually brought on by sudden movements or abrupt sensory input. PKD may be a familial, sporadic/idiopathic, or secondary condition (due to multiple sclerosis, stroke, traumatic brain injury).1

The attacks of dyskinesia in PKD are brief, usually lasting less than 5 minutes,2 and can be precipitated by sudden changes in movement; getting up from a chair and getting out of a car are frequent triggers.3 Movements are often unilateral but may be bilateral. Consciousness is retained. Many individuals may have a brief, nonspecific warning or aura prior to an attack. The interictal presentation is usually normal. Current conventional standard-of-care treatments involve anti-epileptics such as carbamazepine or phenytoin, which can be limiting to patients due to commonly seen negative side effects such as drowsiness, dizziness, and memory problems.

The following case study examines the use of intravenous (IV) vitamin and mineral infusions (modified “Myers’ Cocktail”) for the treatment of symptoms related to PKD in a 58-year-old white female with sudden-onset PKD. The Myers’ cocktail was invented by Dr John Myers, a medical doctor from Baltimore, MD, in the 1970s.4 Dr Myers pioneered the use of IV vitamin and mineral therapy for such conditions as acute asthma attacks, migraines, fatigue (including chronic fatigue syndrome), fibromyalgia, acute muscle spasm, upper respiratory tract infections, chronic sinusitis, seasonal allergic rhinitis, and cardiovascular disease.4 There are currently no case studies in the literature examining the use of the Myers’ cocktail nutrient infusions for the treatment of neurological dyskinesias. This report documents the treatment of a patient with idiopathic PKD using the Meyer’s cocktail nutrient formula. This is the first documented case of its kind, and seeks to inspire further research on the use of IV nutrient infusions for the treatment of neurological dyskinesias.

Case Study

Our patient is a 58-year-old Caucasian female. Her main presenting symptoms included extreme fatigue, impaired cognition, and episodes of slurred, halting speech, and muscle dyskinesias that presented as sudden involuntary neck jerks, a palsy-like gait, and hand tremors. The patient’s symptoms began 13 years prior after a gardening episode exposed her to a plum of molehill dust. At the onset, the patient felt as if all the energy had drained out of her body; she became extremely fatigued, could not speak, and believed she was having a stroke. She was taken to the emergency room, where the source of her symptoms could not be identified. After this episode, the patient reported being bedridden for 2 years. The movement symptoms began around this time, started to occur in episodes lasting up to 5 minutes, and happened multiple times throughout the day, although were not reproducible during visits to her neurologist. For this patient, loud noise was the main trigger for her symptomatic episodes.

The patient’s quality of life was severely diminished due to her condition. She reported being unable to drive, walk up stairs, or perform many activities of daily life, due to her extreme fatigue and fear of having an episode of dyskinesia. The patient has a family history of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) on her mother’s side, and a personal history of episodic depression, irritable bowel syndrome, hypertension, and insomnia throughout her life. A thorough neurological exam was performed by the patient’s neurologist, which did not reveal any in-office positive findings. Home video recording of the patient’s episodes of dyskinesia were obtained, which revealed the patient’s symptoms of involuntary neck-jerking movements, difficulty walking, with a palsy-like gait, slurred and halting speech, and hand tremors. The patient’s neurologist had offered a course of the anti-epileptic drug, carbamazepine, which the patient refused, due to the common side effects of increased fatigue and brain fog (symptoms that the patient was already experiencing to a large degree).

At the time of presentation, the patient was being co-managed by her primary care osteopathic physician, a rheumatologist, and a neurologist. The patient underwent extensive blood work, which was unremarkable and negative for SLE. She was referred to our clinic for initiation of IV therapy after extensive work-up and evaluation by her primary care physician and neurologist, who thought the treatment might provide some relief. On the first visit, the patient was exhibiting signs of neck-jerking, difficulty speaking, and difficulty walking.

Treatment

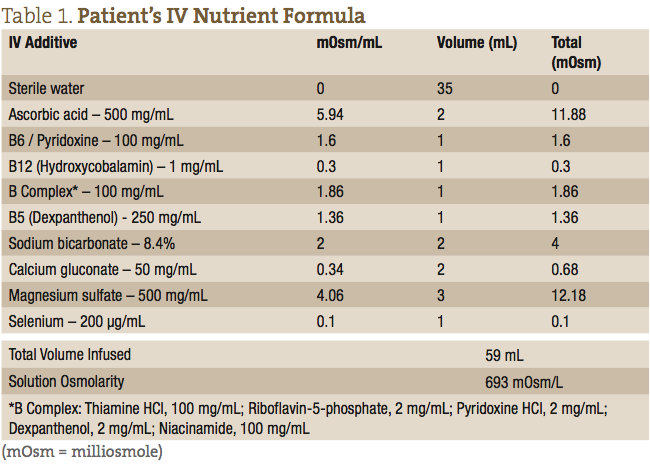

The patient’s IV nutrients were collected in a 60 mL syringe and administered at the antecubital fossa using a 24-gauge butterfly needle. The IV formula consisted of a 59 mL weekly dose, as outlined in Table 1.

Follow-up & Outcomes

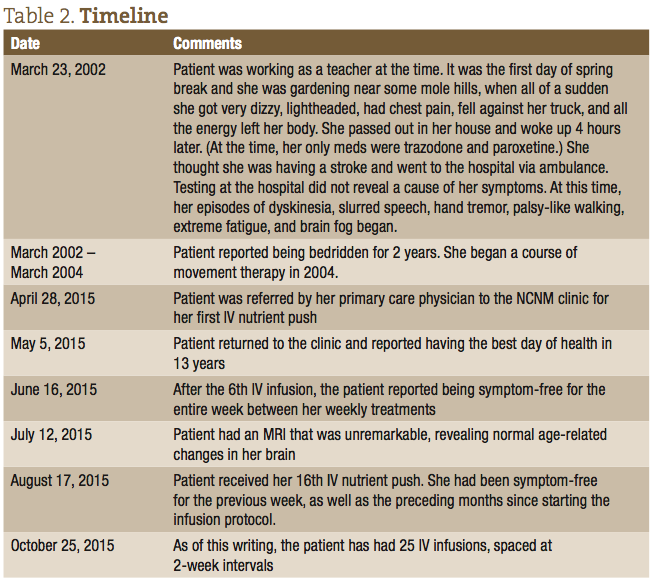

After the first IV infusion, the patient returned the following week and reported feeling better than she had in 13 years since she first started experiencing symptoms. She reported that all her major symptoms of dyskinesia, and difficulty walking and speaking, were dramatically reduced. She did report, however, that the effect only lasted a few days after that initial IV, and then her symptoms returned. After approximately the 6th consecutive weekly visit, the patient was able to remain symptom-free for the entire week between treatments. The patient was able to resume activities of daily living (ADLs), walking up stairs, gardening, and regaining a normal quality of life. The timeline of her treatments and progress is listed in Table 2.

Discussion

The treatment focus at this point is to get the patient to a place where the IV therapy can be spaced out for longer intervals, while at the same time keeping her symptom-free. At the 13th IV infusion, the treatment plan was expanded to include intramuscular (IM) injections of magnesium sulfate (1.5 cc), methylated B12 (0.5 cc), and B complex (0.5 cc). This was based on the thinking that these nutrients were the primary ingredients in the treatments that were abating her symptoms, and that IM injections, with their slower release into the bloodstream, would maintain her symptom-free for longer. As of this writing, the patient has had 25 IV Infusions, spaced at 2-week intervals, with an IM injection performed at home between office visits.

Of the nutrients contained within this formula, the most studied in the treatment of neurological disorders are magnesium sulfate, B12, and B6 (pyridoxine). A 2007 randomized controlled trial, published in the Journal of Clinical Psychology, examined the effects of 1200 mg daily oral supplementation of B6 for tardive dyskinesia, and found significant improvement of symptoms in the treatment group compared to placebo.5 Tardive dyskinesia is a neurological disorder characterized by involuntary movements of the face, jaw, trunk, and extremities, and which shares many of the symptoms found in PKD. Pyridoxal phosphate (PLP), the metabolically active form of vitamin B6, is a cofactor in the production of the neurotransmitters dopamine, serotonin, epinephrine, norepinephrine, and GABA. Lack of dopamine, in particular, is associated with many movement disorders, primary of which is Parkinson’s disease, and may play a role in other dyskinesias as well.5

Vitamin B12 supplementation has been studied extensively with regard to its effects on symptoms of peripheral sensory and motor nerve dysfunction. A 2012 cross-sectional study, published in the Journal of American Geriatrics, showed an association between low vitamin B12 levels and impaired peripheral motor and sensory nerve function.6 Several large-scale studies and subsequent reviews have demonstrated positive results using vitamin B12 supplementation in the treatment of diabetic neuropathy.7 Recent research on the mechanism-of-action of B12 (and B12 deficiency) shows its impact on a network of cytokines and growth factors in the central and peripheral nervous system, some of which are neurotrophic, others neurotoxic.8 The study provides evidence suggesting that vitamin B12 deficiency may result from upregulation of neurotoxic cytokines and downregulation of neurotrophic factors.8

In a 2003 study published in the Journal of Experimental Neurology, magnesium citrate, in doses of 50-200 mg/kg, was shown to significantly reduce parkinsonian dyskinesia in Parkinson’s-induced monkeys.9 Another study, published in 2005 in the Journal of Anesthesia and Analgesia, looked at the ability of magnesium sulfate to prevent post-anesthesia myoclonic movements and pain in patients undergoing etomidate anesthesia.10 The group that received magnesium sulfate prior to induction with etomidate experienced fewer myoclonic movements and pain compared to controls who did not receive magnesium sulfate prior to induction. In the nervous system, magnesium acts as a depressant by competing with calcium for presynaptic receptor activation and neuronal release of acetylcholine.11 This mechanism of action may also explain its efficacy as an anticonvulsant, most successfully in eclampsia.12

It is difficult to ascertain what exactly in the combined nutrient cocktail is having the greatest effect on the patient’s neurological symptoms. Research into B6, B12 and magnesium sulfate all show positive effects on a range of neurological symptoms. These nutrients are most likely the active constituents in the IV nutrient formula. However, it would be difficult to say that these nutrients administered separately would have produced the same beneficial outcome, as their effects may be acting synergistically along several different biochemical pathways in the body.

This case documents the successful side-effect-free treatment of an idiopathic dyskinesia. Given the relatively low cost and the profound symptom relief that the treatments offer, IV nutrient therapy has tremendous potential in the treatment of neurologic dyskinesias and further research is warranted.

Mark Iwanicki is a 5th year naturopathic and Chinese medical student and clinical intern at the National College of Natural Medicine (NCNM). Originally from Brooklyn, NY, Mark went to Cornell University for his undergraduate degree where he studied business marketing and was a pre-veterinary medical student. After college, Mark co-founded Innovative Medicine LLC, a holistic medicine distribution and education company. Mark’s areas of educational interest include neurology, oncology, and autoimmune conditions.

Mark Iwanicki is a 5th year naturopathic and Chinese medical student and clinical intern at the National College of Natural Medicine (NCNM). Originally from Brooklyn, NY, Mark went to Cornell University for his undergraduate degree where he studied business marketing and was a pre-veterinary medical student. After college, Mark co-founded Innovative Medicine LLC, a holistic medicine distribution and education company. Mark’s areas of educational interest include neurology, oncology, and autoimmune conditions.

Leslie Fuller, ND, is a 2009 graduate of NCNM. Following graduation she completed a 2-year residency program, where she focused on the medical management of many chronic healthcare issues, including diabetes, hypertension, asthma, allergies, hormonal imbalance, and digestive problems. She has been actively involved in the health and wellness arena, with a focus on sports medicine, neurologic disability, and IV therapy for well over 15 years. Dr Fuller currently teaches Neurology and IV Therapy, as well as sees patients clinically at NCNM.

Leslie Fuller, ND, is a 2009 graduate of NCNM. Following graduation she completed a 2-year residency program, where she focused on the medical management of many chronic healthcare issues, including diabetes, hypertension, asthma, allergies, hormonal imbalance, and digestive problems. She has been actively involved in the health and wellness arena, with a focus on sports medicine, neurologic disability, and IV therapy for well over 15 years. Dr Fuller currently teaches Neurology and IV Therapy, as well as sees patients clinically at NCNM.

References

- Bhatia KP. The paroxysmal dyskinesias. J Neurol. 1999;246(3):149-155.

- Bruno MK, Hallett M, Gwinn-Hardy K, et al. Clinical evaluation of idiopathic paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesia: new diagnostic criteria. Neurology. 2004;63(12):2280-2287.

- Familial paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesia. Reviewed January 2014. Genetic Home Reference Web site. http://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/familial-paroxysmal-kinesigenic-dyskinesia. Accessed August 4, 2015.

- Gaby AR. Intravenous nutrient therapy: The “Myers’ cocktail.” Altern Med Rev. 2002;7(5):389-403.

- Lerner V, Miodownik C, Kaptsan A, et al. Vitamin B6 treatment for tardive dyskinesia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(11):1648-1654.

- Leishear K, Boudreau RM, Studenski SA, et al. Relationship between vitamin B12 and sensory and motor peripheral nerve function in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(6):1057-1063.

- Sun Y, Lai M-S, Lu C-J. Effectiveness of vitamin B12 on diabetic neuropathy: systematic review of clinical controlled trials. Acta Neurol Taiwan. 2005;14(2):48-54.

- Leishear K, Ferrucci L, Lauretani F, et al. Vitamin B12 and homocysteine levels and 6-year change in peripheral nerve function and neurological signs. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2012;67(5):537-543.

- Chassain C, Eschalier A, Durif F. Antidyskinetic effect of magnesium sulfate in MPTP-lesioned monkeys. Exp Neurol. 2003;182(2):490-496.

- Guler A, Satilmis T, Akinci SB, et al. Magnesium sulfate pretreatment reduces myoclonus after etomidate. Anesth Analg. 2005;101(3):705-709.

- Noronha JL, Matuschak GM. Magnesium in critical illness: metabolism, assessment, and treatment. Intensive Care Med. 2002;28(6):667-679.

- Euser AG, Cipolla MJ. Magnesium sulfate for the treatment of eclampsia: a brief review. Stroke. 2009;40(4):1169-1175.