Katy Nelson, ND

WANTED: PEAK EXPERIENCE – CLEAR SKIN

DD is my 45-year-old client with cystic acne, and this is the story of our cooperative chase and “challenge to summit.” After more than 30 years of risky and transitory successes using conventionally pharmaceuticals for acne, and despite achieving a rather model lifestyle, DD is still hungry to attain a clear complexion.

She contacted me while I was “out-post” living in Florida, caring for my elderly mother and accepting very few clients. Her case interested me, though. DD had the overt signs of hormonal imbalance: menstrual irregularities; worsening after oral contraceptives (OCP); acne onset at puberty; the “4 Fs” (female, fair, 40s, and fat); along with a clinically tantalizing evanescence. All of these suggested a deeper pituitary involvement. I was familiar with the associations between facial and back acne, high testosterone levels, and polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) in women, but I’d had no prior clinical experience with this syndrome.

DD’s presentation included practiced record-keeping and an exercised level of commitment. In hindsight, these have provided a “base camp” without which this review would be impossible. My compliments to and appreciation of DD, whose experience is underscoring the need of new research on the subject (some of which we found) and our continued experimentation. We welcome your comments.

A case attribute: DD and I have never met in person.

Intake & History

On May 3, 2013, I conducted a general intake on DD, a 43-year-old white female. She described herself and her history as follows:

- Weight: 150 pounds, with a maximum weight of 162 pounds 2 years prior

- Exercise: 60 minutes of yoga 6 times weekly; 30 minutes of walking 3-5 times weekly

- Medications: None

- Surgeries: None

- Supplements: Ayurvedic botanicals; quercetin; Urtica dioica (nettles); vitamin D; blood-cleansing botanicals

- Family history: Positive for hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and obesity (father); and allergies, “arthritis,” and obesity (mother)

- Diet: “Mostly vegan.” No meat for 2 years; fish 3 times per year; dairy 4 times per year; enjoys cooking. The foods that she finds hardest to give up include sweets, carbs, including bread; and pizza. Negative for use of tobacco, recreational drugs, or coffee; positive for alcohol 2-3 times per week, chocolate 3 times weekly (2013), and daily peanut butter cup (2014)

- Lifestyle: 20 hours of work per week; happily married for 15 years; husband’s stressful work affects her stress level; sleeps 5-7 hours per night. Emotions: “I mostly worry about what other people will think about me.”

- Acne history: Significantly, her skin was at its best while her weight was at its lowest

Reproductive History

- Menarche “age 12 or 13”; no pregnancies; negative for uterine fibroids or breast fibrosis; 15-year history of OCP use; inconsistent periods, with cycle length as short as 1 day; menses stopped in July, 2010, and restarted in December, 2011

- Her OB/GYN recommended hysterectomy or ablation

Initial Assessment, May 14, 2013

DD’s increased flow length and shortened cycle length made me suspect a relative progesterone deficiency. Suboptimal levels of progesterone are extremely common among the women I counsel and, I believe, in general, among US women over age 35, due to aging and dietary deficiencies (especially omega-3 fatty acids). With cycling women I use a cycle-spanning saliva sampling to assess estrogen and progesterone levels, along with pooled values of DHEA+DHEA-S and testosterone. Due to the intuited pituitary involvement, I also ordered salivary luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH).

Lab Results: Confirmation

DD’s lab results suggested the following imbalances, as stated in the accompanying report commentary:

- “luteal phase progesterone deficit (Type 1 – shortened phase, less than 12 days)”

- “luteal phase progesterone deficit (Type 3 – suboptimal distribution over luteal phase)”

Normal luteal phase levels of salivary progesterone range from 65-500 pg/mL; DD’s highest luteal value was 149 pg/mL on Day 15.

Other interpretations on the report included the following:

- “normal timing of pre-ovulatory estradiol peak, but blunted peak output”

- “optimal timing with respect to ovulation”

- “normal luteal phase estradiol output”

Her “Follicular Estrogen Priming Index” (an estimate of estrogen exposure in target tissues) was 598 (reference range: 282-1410), consistent with peri-menopause and signifying “reduced functional impact of progesterone on E2 [estradiol] sub-primed tissue” (uterus, breast, brain, bone, skin, etc). The laboratory added, “bones require optimal E2 and P balance for long periods to reverse osteoporosis.”

Before testing, I had suspected insufficient progesterone and that this might reduce the normal luteal downregulation of estrogen. However, testing showed that despite insufficient progesterone over insufficient time, estrogen values were relatively normal.

Her free salivary testosterone (TTF) was high at 47 pg/mL (reference range:10-38 pg/mL).

Her pooled DHEA+DHEA-S value was 10 ng/mL (male/female reference range: 3-10 ng/mL).

LH & FSH, and the Question of PCOS

While DD’s free testosterone was high enough to suggest PCOS, I expected to also find a high ratio of LH to FSH (favoring increased ovarian testosterone output). Instead, her LH:FSH ratio was 1:1.97 (LH=238 mIU/mL; FSH=470 mIU/mL), discounting the likelihood of PCOS (in which the LH:FSH ratio is typically >2.5:11). Her salivary FSH value suggested reduced ovarian response, normal for her age, while her low LH value confirmed my intuition of pituitary involvement. Through negative feedback, high testosterone inhibits pituitary LH output,2 which would likely correlate with lower progesterone output, since an LH surge is required for ovulation and subsequent corpus luteum formation.

Initial Treatment & Response

On 8/16/13, I wrote DD prescription for a cyclic nightly dose of a compounded, soy-free, wild yam-based progesterone (P), to be administered as a sublingual liquid (100 mg/mL). Initially, there was some difficulty in determining an appropriate maximal dose and timing it “mid-cycle.”

Initial results included improvement in the length of her cycle, and the duration and volume of flow. However, at a highest P dose of 0.5 mL (50 mg) a new symptom of breast tenderness developed, a pattern that repeated itself when this same dose was tried again later. A dose of 0.35 mL became our de facto highest dose. Cycle improvements were unmatched, however, by significant qualitative or quantitative improvement in her acne, making DD anxious to move on to a protocol that included Vitex agnus, a progesterone agonist.

Vitex agnus

The use of Vitex agnus (chaste berry), known to enhance progesterone levels,3 was recommended to us by Kamal Henein, MD, with whom I consulted on the case. On 10/12/13, during Cycle #2, she began with a Vitex dose of 10 gtt BID, and we monitored her response; 2 days later, she increased the dose to 30 gtt BID.

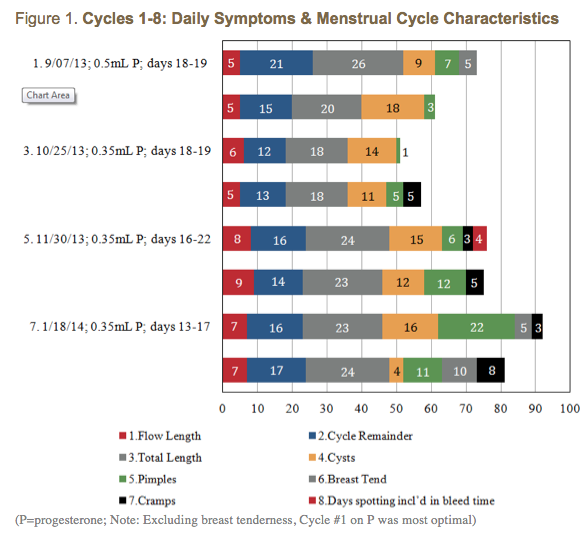

Vitex is slow-acting,4 requiring several cycles to become most effective. Higher doses are more common, but because she continued with the pharmaceutical-grade progesterone prescription, I recommended a lower dose of Vitex. The data in Figure 1 suggests that the Vitex may have begun kicking in around Cycle #5. Improvements in her cycle may also be attributable to getting her highest doses of P nearer to mid-cycle, as was the case for Cycles #7 and #8 (Figure 2).

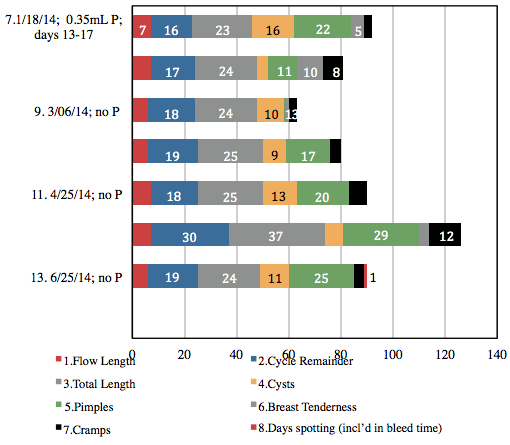

Perhaps due to Vitex’s pituitary effect, DD wrote “The one thing I think has made the most difference is the Vitex.” Accordingly, she wanted to increase her dose of Vitex, and decrease or discontinue the P. I advised her to taper the P during, and ending with, Cycle #8, as well as to increase her dose of Vitex to 50 gtt BID mid-cycle (Cycle #8). Due to a miscommunication, she increased and stayed on the Vitex at 50 gtt TID.

The 37-day length of Cycle #12 begs the question, “Was the Vitex substantially kicking in to the point of feeding back as “pregnancy”? And were depleted P reserves no longer influencing estrogen downregulation?” I had DD discontinue the Vitex altogether, and her period started the next day. The data reflecting higher dosing of Vitex shows greater consistency, which DD appreciated; however, cycle length was shorter, flow length was longer, she had increased cramping, and more moodiness and breast tenderness, and minimal, if any, improvement in cyst and pimple outbreaks.

Effects on the Acne

I felt that organizing her acne data into cycle quarters might be clinically revealing. On the P alone, outbreaks were limited to the last 2 quarters of the cycle, whereas on the P+Vitex, and Vitex alone, outbreaks occurred in almost every quarter.

Peculiarly, in contrast to what the data suggests, DD wrote, “When you increased my dose of Vitex [on 2/22/14, during Cycle #8], I gradually started to notice less acne over several months. I was still getting a few pimples, but the cysts had pretty much stopped.

She then wrote, “after stopping the Vitex [6/21/14, toward the end of Cycle #12], my skin has definitely taken a turn for the worse … cysts again all over my chin … deep and painful.” However, she restarted 5 days later, to little avail. Nearly a month after stopping the Vitex, she wrote, “There was much improvement since we started working together. Now [7/21/14] I feel … almost back to where I started.”

The GI Influence

Although DD’s diet was far from being the Standard American Diet (SAD), about 6 months after beginning hormonal therapy (3/17/14), we ran some GI and food allergy tests on her. Results were positive for immune sensitivity to soy and egg; borderline-positive sensitivity to gliadin; and “equivocal” sensitivity to milk. Other results included: ova and parasites (none seen); yeast (none isolated); intestinal flora (heavy growth of desirable rods/flora); and unexpectedly, negative for intestinal inflammation. The only near-significant finding was heavy growth of non-pathogenic E coli and Strep peroris.

We reviewed her diet for water-soluble fiber intake, as well as that of omega-3 EPA and DHA (with an emphasis on DHA) – fatty acids that help maximize hormonal modulation.

On July 21, 2014, she wrote “I think the diet modifications may have helped somewhat.”

Follow-up Testosterone Testing & Analysis

On 7/5/14 we ran a 4-sample follow-up spot test of her free testosterone (TTF). Results showed a pooled AM TTF value of 21 pg/mL, and a pooled PM TTF value of 15, both down from 47 pg/mL in the previous testing. Perhaps correlating with DD’s perception of improvement, we had successfully lowered her TTF over 10 months, yet without “summiting.”

Testosterone biochemistry, including its feedback loops to the brain, involves the following:

- ↓ T → ↑ hypothalamic release of GnRH → ↑ pituitary release of LH

- Via negative feedback, ↑ LH → ↑ T → aromatization to E2 → ↓ GnRH → ↓ LH → ↓ T

Concordant with DD’s perception of acne improvement on Vitex, I had first thought that her lower TTF might be linked to botanically increasing her LH. However, more recent research has ruled out a stimulatory effect of testosterone on LH.3 One possible factor involved in her clinical response is prolactin (not measured), which is known to interfere with corpus luteum formation3 and has also been linked to hirsutism in women.5 In vitro, Vitex has been shown to inhibit prolactin in pituitary cells.3

New Strategy

I began to consider the possibility of adrenal involvement in DD’s symptoms. Her initial pooled DHEA+DHEA-S value on 7/18/13 had been 10 ng/mL (reference range: 3-10 ng/mlL). Recollecting this fact was an “Aha -in-the-HPA” moment, in terms of an adrenal component. A Medscape article6 discussing androgen excess in women reinforces this idea:

- Sex hormone-binding globulin (SHGB) binds 80% of testosterone, and SHGB levels are increased by E2 and decreased by other androgens, obesity, and hyperinsulinemia;

- Peripheral tissues such as fat, skin and liver … [convert] DHEA to testosterone;

- Testosterone production in women is 25% ovarian (LH-dependent) and 25% adrenal; and

- Androgenic DHEA production is 20% ovarian and 80% adrenal. DHEA-S is exclusively adrenal.

As of this writing, DD is experimenting with a series of adrenal-support supplements, to be taken following a washout period from the Vitex:

- Taurine, for its ability to reduce anxiety and promote calmness

- A proprietary botanical amino acid combination taken nightly, for its ability to reduce anxiety and reset hypothalamic and pituitary cortisol receptors

- A single adaptogenic botanical, known for supporting adrenal medullary output

- A proprietary combination of adaptogenic botanicals, vitamins and beta-sitosterol, to which clients with adrenal fatigue have responded well

Follow-up & Comments

As this article goes to the editor, DD reports, “I had very minimal PMS … off the Vitex,… a minor amount of breast tenderness, and virtually no moodiness … my skin was looking pretty good.” Her husband noticed the difference. Concurrent with sampling the adrenal adaptogenics, DD actually experienced increased outbreaks. As she hadn’t been monitoring her soy intake, I wondered if this might have contributed. DD also wondered if nettles were playing a role, after reading an article about nettles increasing testosterone levels in the body. Overall, DD was feeling better, and her cycles were better regulated on the Vitex. The puzzle was clearly not yet solved. Although DD didn’t “reach the summit,” she still felt that the process had been worth it.

Katy Nelson, ND, (Bastyr ’94), with an office since 1997 in Michigan’s rural Upper Peninsula on the shores of beautiful Lake Superior, promotes our nature-devoted profession through consultation, writing, and mentoring. She is joined by Bastyr grad, former mentoree and pediatric specialist, Alicia Smith Dambeck, LAc, CH (also ad locum in St Paul with Amy Johnson Grass, ND). Since 2011, Dr Katy has been ad locum herself in SW Florida for family matters.

Katy Nelson, ND, (Bastyr ’94), with an office since 1997 in Michigan’s rural Upper Peninsula on the shores of beautiful Lake Superior, promotes our nature-devoted profession through consultation, writing, and mentoring. She is joined by Bastyr grad, former mentoree and pediatric specialist, Alicia Smith Dambeck, LAc, CH (also ad locum in St Paul with Amy Johnson Grass, ND). Since 2011, Dr Katy has been ad locum herself in SW Florida for family matters.

References

- Pannill M. Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: An Overview. 2002;2(3). Medscape Web site. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/438597_3. Accessed October 1, 2014.

- Gonadotropins: Luteinizing and Follicle Stimulating Hormones. Colorado State University Web page. http://arbl.cvmbs.colostate.edu/hbooks/pathphys/endocrine/hypopit/lhfsh.html. Accessed October 1, 2014.

- Vitex agnus-castus. [monograph] Altern Med Rev. 2009;14(1):67-70.

- Chaste Berry. [monograph] The Eclectic Physician: A Journal of Alternative Medicine. Available at: http://www.eclecticphysician.com/herbs/vitex.shtml. Accessed October 1, 2014.

- Bode D, Seehusen DA, Baird D. Hirsutism in Women. Am Fam Physician. 2012;85(4):373-380. Available at: http://www.aafp.org/afp/2012/0215/p373.html. Accessed October 1, 2014.

- Abdel-Rahman MY. Androgen Excess. Updated March 28, 2014. Medscape Web site. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/273153-overview#showall. Accessed October 1, 2014.